Democracy on Trial: Ten Pivotal Elections Will Reshape Global Order as Authoritarian Pressures Mount Across Asia, Africa, Europe, and Americas

Executive Summary

A Year of Transformative Democracy: Global Elections in 2026 and the Reconfiguration of Political Order

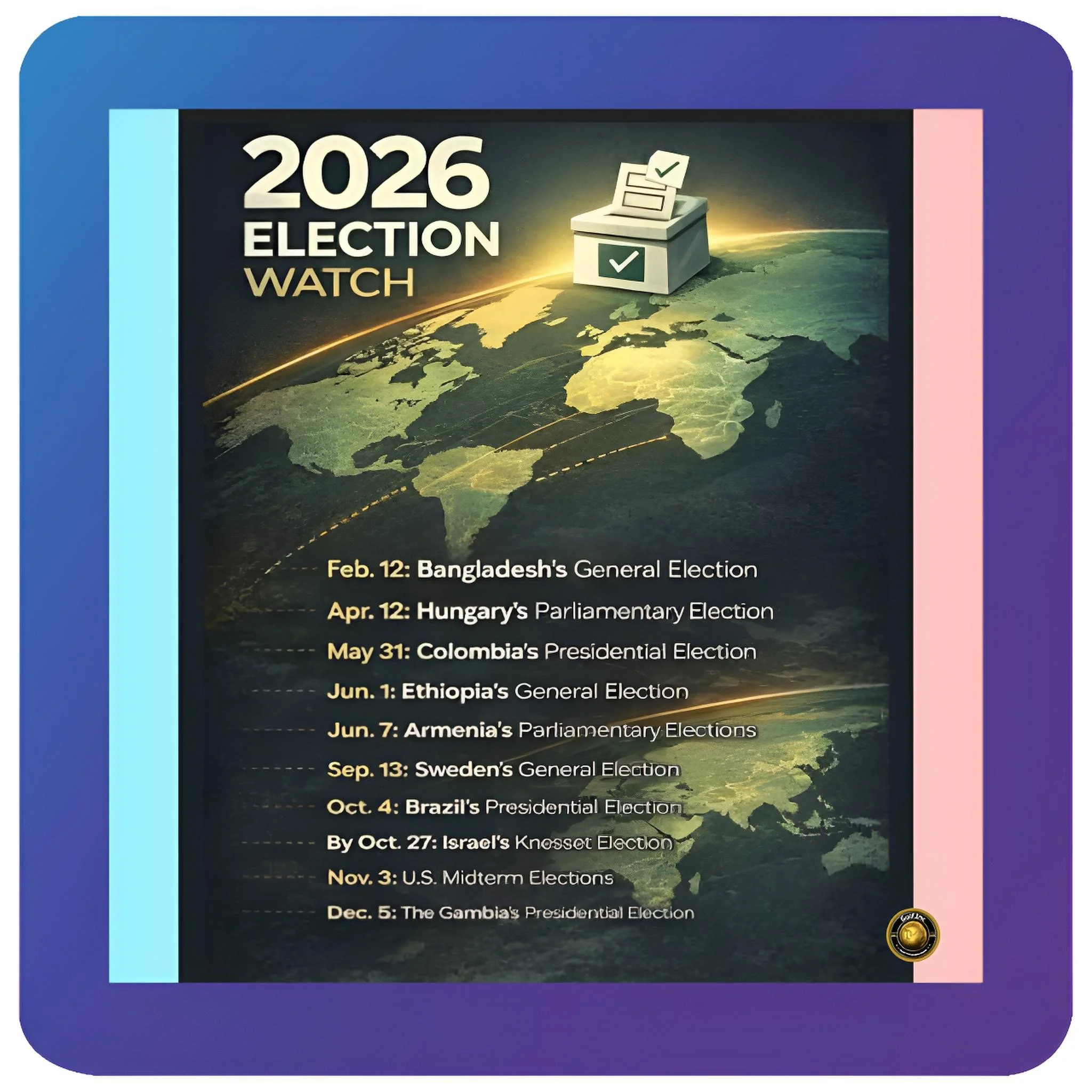

2026 marks an inflection point in global politics, with 10 pivotal elections scheduled to reshape the international order. Spanning from Bangladesh in February through The Gambia in December, these contests will determine not merely electoral outcomes but fundamental trajectories of democratic governance, regional stability, and great power competition.

The collective weight of these elections—involving more than one-third of humanity across diverse geographic and strategic contexts—suggests a year of consequential political reckoning. The defining tension across these contests is the simultaneous demand for democratic renewal and the mounting pressure of authoritarian backsliding, populist mobilization, and institutional erosion.

The November U.S. midterms and October Israeli elections carry outsized geopolitical implications, while elections in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Colombia test the capacity of fragile democracies to navigate political transitions amid conflict and economic stress.

European and Asian elections will signal whether populist and right-wing nationalist movements have peaked or are consolidating power.

The aggregate effect of these choices will determine whether 2026 marks a democratic inflection point or an accelerated descent into institutional fragmentation and great power conflict.

Introduction: Democracy under Siege and the Stakes of 2026

Fragile Democracies Under Fire: Can Interim Governments, Conflict-Affected Regions, and Weakened Opposition Parties Conduct Free, Fair Elections in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Beyond?

Democracy in the twenty-first century faces a paradoxical challenge: it remains the most legitimating form of government globally, yet its substance is hollowing out in countries across the world. This contradiction comes into sharp relief when examining the ten elections scheduled for 2026. The electoral calendar reflects not merely routine democratic renewal but rather critical moments where societies will choose between competing visions of governance, sovereignty, and institutional design.

These elections occur against a backdrop of structural geopolitical fragmentation, with the bilateral relationship between Washington and Beijing defining great power competition, multiple active conflicts (Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, Myanmar, and others) draining resources and political capital, and a generation of younger voters demanding accountability. At the same time, traditional institutions struggle to deliver representation and material improvement in living standards.

The 2026 election cycle exhibits striking geographic and typological diversity, obscuring an underlying thematic coherence. From Bangladesh to The Gambia, from the United States to Israel, voters confront analogous questions: Can democratic institutions resist the cumulative pressure of corruption, conflict, and economic disappointment? Will opposition movements consolidate around coherent alternatives, or remain fragmented and ineffectual?

Are term limits a permanent constitutional feature or a pliable political instrument?

The answers that emerge from these contests will reverberate well beyond their national borders, influencing trade relationships, defense alliances, conflict trajectories, and the rules-based international order itself.

Bangladesh: Democratic Resurrection from Revolutionary Rupture

Bangladesh enters 2026 having undergone a seismic political upheaval that displaced a fifteen-year ruling coalition. In August 2024, student-led protests—morphing into a broader popular uprising—forced Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her Awami League government from power, compelling Hasina into exile in India and leaving behind an interim government led by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus.

The February 12, 2026, general election will be Bangladesh’s first competitive contest in more than a decade and signals either the restoration of genuine democratic contestation or the embedding of a new form of elite consensus under the guise of change.

The electoral landscape has fractured into competing visions of post-Hasina governance. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the leading opposition force during Hasina’s tenure and a target of her systematic repression, emerged as a principal contender, led by former Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia. Jamaat-e-Islami, the largest Islamist party, has signaled openness to coalition governance and is fielding a slate of new candidates to signal generational change in its leadership.

The National Citizens Party (NCP), born of the 2024 uprising, campaigns to create a “Second Republic” predicated on constitutional reconstruction. The Awami League, despite winning four consecutive elections, has been banned from participation, with Hasina sentenced to death in absentia for crimes against humanity—a move that critics argue undermines the election’s legitimacy by excluding a party that commanded substantial electoral support.

The Yunus interim government has scheduled the election to conclude before Ramadan commences on February 17, avoiding religious complications while establishing a political timeline that prevents indefinite unelected governance.

A constitutional referendum will accompany the election on the “July Charter,” a sweeping reform package intended to remake Bangladesh’s constitutional architecture. The underlying cause-and-effect dynamics are clear: decades of Awami League rule under Hasina involved systematic democratic erosion (suppression of opposition parties, control of the judiciary, media censorship, extrajudicial killings), which in turn generated youth unemployment, corruption, and institutional collapse sufficient to trigger a revolution.

The 2026 election offers a potential correction mechanism, but only if the interim authority genuinely permits competitive contestation and respects electoral outcomes. The Yunus government faces pressure to demonstrate that it serves as a neutral arbiter rather than as a vehicle for specific factional interests, a particularly acute challenge given the BNP’s historical tendency toward authoritarian governance when in power.

The consequences of this election extend beyond Bangladesh’s borders. India, a principal geopolitical actor with which Bangladesh shares a 4,000-kilometer border and complex historical ties, will closely monitor whether the new government realigns toward closer cooperation or reasserts greater strategic autonomy. The status of the Rohingya refugee population—nearly one million individuals sheltering in camps in Bangladesh—depends partly on regional power dynamics that shift with political leadership change.

The election’s outcome will also signal whether student-led, mass protest movements remain viable mechanisms for effecting political change in South Asia or whether they will be incorporated into new institutional arrangements that preserve elite interests while appearing to accommodate popular demands.

Elections in South America-2026

Colombia: Peace Process, Populism, and the Leftward Advance in Latin America

Colombia’s May 31, 2026, presidential election occurs within a starkly different context than Central Europe’s democratic stress tests. Here, the contest reflects the broader ideological rightward swing that has characterized Latin America throughout the 2020s, yet simultaneously tests whether the leftward political breakthrough represented by Gustavo Petro’s 2022 election can stabilize and consolidate. Incumbent President Petro—barred by constitutional single-term limits from seeking reelection—has polarized Colombian opinion through his aggressive pursuit of constitutional reform, confrontational stance toward a conservative-dominated Senate, and contentious relationship with the United States over drug policy and military aid.

Petro’s Historic Pact coalition has nominated Senator Iván Cepeda as its presidential candidate. Recent polling from December 2025 shows Cepeda commanding 31.9 percent support, significantly ahead of centrist Sergio Fajardo (8.5 percent) and right-wing outsider Abelardo de la Espriella (18.2 percent). However, this apparent left-wing strength masks deeper electoral volatility.

A contentious climate of political violence has shadowed the campaign: opposition pre-candidate Miguel Uribe Turbay was assassinated in August 2025, two months after being shot while campaigning—a graphic illustration of Colombia’s enduring security challenges.

FARC dissident groups and criminal organizations continue to battle government security forces, undermining Petro’s claims to have reduced violence or advanced the 2016 peace accords. Petro’s unpopularity among business elites and conservative constituencies, combined with his conflicts with the U.S. Trump administration over drug policy, has created economic headwinds and investment uncertainty.

The election’s structural dynamics reveal competing visions of Colombia’s future. Cepeda represents continuity with Petro’s peace-oriented, social-democratic agenda—emphasizing labor rights, environmental protection, and inclusion of historically marginalized populations. Fajardo embodies centrist pragmatism, promising slower reform and greater accommodation of business interests.

De la Espriella appeals to voters frustrated by rising crime and to those who promise strong anti-corruption measures coupled with conservative social policies. If no candidate receives 50 percent of the vote in the first round (a likely scenario given the fragmented field), a runoff between the top two vote-getters will determine the outcome.

The cause-and-effect dynamics illustrate why Colombia’s election matters beyond its borders. Petro’s presidency attempted a fundamental reorientation of Colombian development strategy away from security-first approaches toward peace and social investment. The results have been mixed: security indicators have not dramatically improved, economic growth has slowed, and business confidence has eroded.

The May 2026 election will signal whether Colombian voters prioritize a redistributive, peace-oriented agenda or revert to a security-first governance that prioritizes business interests and an alliance with the United States.

This choice has implications for regional stability (affecting Venezuela, Ecuador, and Central America), for the durability of peace agreements in fragile post-conflict settings globally, and for whether Latin America’s leftward political shift represents a sustained realignment or a temporary deviation from the continent’s historical conservative trajectory.

Brazil: Aging Incumbent Against Fractious Right-Wing Opposition

Brazil’s October 4, 2026, presidential election will shape Latin America’s largest economy and its regional influence throughout the remainder of the decade. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, at age 80, is pursuing a fourth non-consecutive term after initially promising in 2022 that he would not seek reelection. Lula reversed that decision, declaring in October 2025 that “you can be sure I have the same energy I had when I was 30” despite considerable evidence to the contrary.

Lula’s principal rival is likely to be Tarcísio de Freitas, the right-wing governor of São Paulo state, or possibly one of Jair Bolsonaro’s sons (Flávio or Eduardo). However, Bolsonaro himself remains barred from candidacy due to a 2023 conviction for inciting a coup and currently serves a twenty-seven-year prison sentence.

Recent polling from November 2025 shows Lula defeating de Freitas 46-39 percent in a hypothetical runoff. However, this lead reflects temporary rally-around-the-flag effects from Lula’s clashes with the Trump administration over tariff threats.

The Brazilian electorate remains volatile: the 2022 election saw the narrowest margin in modern history (1.8 percentage points), suggesting that any seat-of-the-pants campaign surprises, economic deterioration, or criminal charges against candidates could substantially shift electoral dynamics.

Brazil’s economy presents serious headwinds for the incumbent. GDP growth has slowed sharply, inflation hovers just below 5 percent, and the Trump administration’s 50 percent tariff threats create additional economic uncertainty. Brazil’s homicide rate remains among the world’s highest despite intensive security operations, undermining Lula’s ability to claim credit for improvements in public order.

The election will determine whether Brazilian voters prioritize Lula’s social spending programs and infrastructure initiatives or revert to right-wing governance emphasizing security, business-friendly policies, and closer alignment with the United States.

Elections in Africa - 2026

Ethiopia: Electoral Legitimacy Amid Existential Instability

Ethiopia’s June 1, 2026, general election exemplifies the fundamental paradox facing Africa’s most populous nations: the simultaneous demand for democratic renewal and the persistence of armed conflict that renders free and fair polls technically impossible.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has declared the forthcoming vote will be “the best organized election in Ethiopia’s history,” a claim that rings increasingly hollow when measured against observable ground realities.

The context is stark and deteriorating. Ethiopia emerged from a devastating 2020-2022 civil war between federal forces and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front that killed an estimated 600,000 people and displaced more than one million.

Regional conflict persists in the Oromia, Amhara, and Somali regions, with insurgent movements continuing to challenge federal authority. The ruling Prosperity Party, which won 96.8 percent of parliamentary seats in the flawed 2021 elections, relies on coercive mechanisms inherited from its predecessor (the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front) to maintain control.

The anticipated outcome of the June 2026 election is predetermined: the Prosperity Party will dominate through a combination of security force intimidation, restricted electoral competition, and administrative manipulation.

The deeper pathology is instructive for understanding democratic collapse in post-conflict settings. By prioritizing the performance of elections over the preconditions for genuine democratic contestation—namely security, political inclusion, and consensus on constitutional rules—the Abiy government is manufacturing the appearance of democratic legitimacy while consolidating authoritarian rule.

In regions gripped by conflict, voters cannot safely assemble to campaign or vote. In areas where the Prosperity Party faces genuine competition, the security apparatus prevents opposition party activity.

The proposed new civil society law threatens to criminalize undefined “political advocacy” and eliminate judicial oversight of government restrictions on civil society organizations.

Hanging over the election is the possibility of renewed war with neighboring Eritrea. This prospect would simultaneously provide the Abiy government with a national emergency justifying authoritarian measures while destabilizing the entire Horn of Africa region.

Ethiopia’s August 2025 ultimatum to Eritrea regarding border issues, combined with Eritrea’s continued military support for the Fano insurgency in Ethiopia’s Amhara region, suggests the risk of interstate conflict is non-negligible.

If war breaks out during the electoral period, the Prosperity Party’s narrative of providing security and stability would collapse, potentially triggering a wider regional conflagration involving Sudan (gripped by civil war), Somalia (facing domestic instability), Djibouti, and Kenya.

The election’s significance extends beyond Ethiopian borders to the entire future of democratic governance in the Horn of Africa and in post-conflict transitions globally. If the Abiy government successfully executes a flawed election while continuing warfare in peripheral regions, it will demonstrate that electoral authoritarian systems can indefinitely sustain legitimacy claims despite blatant violations of democratic principles.

Alternatively, if electoral manipulation proves insufficient to contain political volatility and renewed conflict erupts, the catastrophic humanitarian consequences will reverberate across the region, imposing high costs on international peacekeeping efforts and development initiatives.

The Gambia: Term limits as a political Landscape.

The Gambia’s December 5, 2026, presidential election presents perhaps the starkest case of democratic backsliding among this year’s electoral calendar.

President Adama Barrow, who came to power in a 2016 surprise victory that displaced the long-serving authoritarian Yahya Jammeh, has engineered parliamentary rejection of a proposed constitutional amendment that would have imposed two-term limits on future presidents.

Barrow’s first seven years in office represented a democratic opening relative to Jammeh’s regime: he expanded judicial independence, restored press freedom, reduced political repression, and permitted civil society organizations to operate.

Upon reelection in 2021, Barrow explicitly endorsed term limits as part of his “legacy.” Yet in 2025, when parliament had an opportunity to ratify a constitutional amendment imposing such limits, the measure failed due to a loophole: the draft language would have permitted Barrow himself to run for two additional terms.

This reversal signals a familiar pattern in African electoral politics: democratic reformers, once consolidated in power, abandon term limit commitments and engineer their own constitutional extension.

Polling shows that most Gambians oppose Barrow’s pursuit of a third term, yet opposition parties remain deeply divided. The main opposition, the United Democratic Party, is fractured, with numerous senior officials having abandoned the party. The electoral mechanism employed in The Gambia (marbles inserted into color-coded drums rather than ballot papers) provides unusual opportunities for election administration manipulation.

The December 2026 election will thus signal whether The Gambia is reverting to the pattern of entrenched authoritarian rule that it appeared to have rejected in 2016, or whether electoral competition can still produce genuine alternation of power.

Elections in Europe -2026

Armenia: Peace, Identity, and Geopolitical Realignment

Armenia’s June 7, 2026, parliamentary election represents an entirely different category of electoral contest: one where voters are asked not merely to choose among competing candidates or parties, but to fundamentally reimagine their nation’s identity and place in the regional and global order.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has staked his political future on his “peace agenda”. Specifically, the Agreement on Peace and the Establishment of Interstate Relations with Azerbaijan was signed in March 2025 and brokered by the Trump administration with U.S. assistance.

The geopolitical logic is compelling but politically fraught. Armenia, a landlocked Christian nation of approximately three million people surrounded by Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Georgia, has endured three decades of conflict with Azerbaijan over disputed territory (Nagorno-Karabakh).

This conflict cost Armenia tens of thousands of casualties, displaced hundreds of thousands of civilians, and left the country economically isolated and strategically dependent on Russia.

Pashinyan’s peace agreement envisages normalizing relations with Azerbaijan, opening transport corridors connecting Armenia to the broader regional economy, and potentially reducing Armenia's reliance on Russian military and economic support. In September 2025, Pashinyan announced that if his Civil Contract party retains power, he intends to adopt a new constitution creating a “Fourth Republic of Armenia” that would accept Armenian sovereignty within its current borders and abandon historical territorial claims.

Yet public trust in Pashinyan stands at 13 percent, reflecting both disillusionment with his failure to prevent military defeat in the 2020 and 2022 wars with Azerbaijan and skepticism toward his peace agenda.

The opposition coalition, comprising the nationalist Armenian Revolutionary Federation-Dashnaktsutyun (ARF-D) and the Kocharyan-led “Hayastan” alliance, contests the peace agreement’s terms, fears that Armenia will become further economically dependent on Turkey and Azerbaijan, and questions whether Pashinyan is negotiating as a representative of Armenian national interests or as a proxy for American strategic goals.

Russia, Armenia’s historical security guarantor, has watched with concern as the U.S. has positioned itself as a broker of Armenian-Azerbaijani reconciliation, seeing this as a displacement of Russian regional influence.

The cause-and-effect mechanisms at work are subtle but consequential. Conflict creates specific structural dependencies (Armenia’s need for Russian weapons and security guarantees; reliance on India and Iran as economic partners), while peace creates different dependencies (need for Turkish and Azerbaijani market access; transition to a non-military economy; possible NATO integration).

Pashinyan’s gamble is that achieving peace will ultimately strengthen Armenia by diversifying its strategic partnerships and integrating it into regional and global economies.

The opposition fears that peace on the terms offered will amount to a capitulation that diminishes Armenia’s sovereignty and leaves it vulnerable to continued pressure from larger neighbors.

The outcome of the June 2026 election will determine Armenia’s trajectory for decades. If Pashinyan retains power, Armenia will likely move forward with constitutional reform, deepen peace negotiations with Azerbaijan, and gradually pivot toward more formal ties with Western institutions (potentially NATO partnership frameworks).

If the opposition prevails, Armenia will likely remain in a state of indefinite conflict, possibly deepen its integration with Russia and Iran, and resist American-led regional realignment initiatives.

The geopolitical implications are substantial: a more Western-aligned Armenia would accelerate the marginalization of Russian influence in the Caucasus, while an opposition victory would suggest the limits of American-brokered regional initiatives in former Soviet spaces where Russia retains substantial leverage.

Hungary: Democratic Backsliding and the Challenge of Opposition Consolidation

Hungary represents the textbook case of democratic backsliding in contemporary Europe. Viktor Orbán has governed the country for 15 of the last 24 years, leveraging supermajority control of parliament to systematically erode judicial independence, subordinate public institutions to political power, rewrite electoral rules in his favor through gerrymandering, and restrict the space for opposition voices.

The April 12, 2026, parliamentary election will determine whether this “illiberal” model has exhausted public tolerance or whether Hungarian voters will extend Orbán’s mandate despite 15 years of authoritarian institutional consolidation.

The critical development in Hungarian politics has been the emergence of Péter Magyar and his Tisza Party as a credible opposition force. In February 2024, a corruption scandal involving presidential pardons led to the resignations of President Katalin Novák and Justice Minister Judit Varga.

Magyar, Varga’s ex-husband, published a Facebook declaration accusing Orbán’s regime of operating as a deliberate political construction designed to obscure massive wealth transfers to politically connected insiders and to concentrate power.

Magyar’s subsequent rallies attracted tens of thousands of supporters, and polling data from the 2024 European parliamentary elections showed Tisza capturing 30 percent of the Hungarian vote—the strongest non-Fidesz performance in nearly two decades.

Current opinion polling for the April 2026 elections shows Fidesz maintaining 37-44 percent support while Tisza polls at 6-7 percent nationally, though some surveys position Tisza as competitive in Budapest and other opposition strongholds.

Orbán has responded to this electoral threat by implementing a redistricting law that redraws constituency boundaries to pack opposition voters into larger districts while fragmenting Fidesz-supporting areas into multiple smaller constituencies—a textbook gerrymandering strategy.

The ruling party has also threatened further electoral law changes, including potentially abolishing the “winner compensation” mechanism if Tisza appears poised to form a government, thereby minimizing the scale of any opposition defeat.

These institutional manipulations underscore a core strategic reality: authoritarian leaders, even when facing genuine electoral competition, possess the power to alter the rules governing the contest before voters cast ballots.

The question for Hungary is not merely whether Orbán’s coalition can command a majority of votes, but whether the electoral system itself has been so thoroughly rigged that victory becomes impossible without collapsing legitimacy or triggering external pressure from European Union institutions.

The cause-and-effect chain at work in Hungary reveals how democratic backsliding operates in the twenty-first century. Rather than banning opposition parties outright, Orbán has gradually rewritten the rules governing political competition, media access, campaign finance, and electoral administration in ways that systematically advantage his party while rendering opposition victory mathematically unlikely even if incumbent dissatisfaction runs deep.

Hungary’s April 2026 election will test whether such institutional engineering can indefinitely sustain electoral hegemony or whether widespread frustration with economic stagnation, high energy costs, and visible corruption will generate sufficient electoral rebellion to overcome gerrymandered disadvantage.

Sweden: Populism, Security, and European Realignment

Sweden’s September 13, 2026, general election offers a window into European electoral dynamics amid rising populist pressure and intensified great power competition. The country has been governed since 2022 by a center-right coalition comprising the Moderate Party, the Sweden Democrats (a right-wing populist party), the Christian Democrats, and the Liberals.

The government confronts structural challenges, including rising gang violence, energy security amid Europe’s rearmament, and debates over immigration and integration.

Current polling shows the opposition Social Democrats (led by Magdalena Andersson) commanding 30-34 percent support, making them the largest party in most surveys. However, potential coalition partners on the center-left (the Left Party, Greens, Centre Party) are polling poorly, collectively insufficient to form a majority without requiring the Social Democrats to govern as a minority administration or make unattractive coalitional compromises.

The Sweden Democrats, the right-wing populist party, poll at 20-21 percent, making them the second-largest political force and a potential coalition partner for any center-right government seeking a stable majority.

The election’s security dimension is particularly significant. Sweden, which abandoned decades of military non-alignment to join NATO in 2024, faces intensified Russian hybrid warfare, including cyber attacks, disinformation campaigns, and critical infrastructure sabotage. Sweden’s Civil Defense Minister warned in December 2025 that the country faces a “serious security situation” heading into the general election, with Russia actively attempting to influence electoral outcomes through information warfare.

The 2026 election will thus carry implications not merely for Swedish domestic policy (energy strategy, immigration, social spending) but for European security architecture and NATO’s cohesion amid U.S. strategic uncertainty under the second Trump administration.

Elections in the United States and Israel

Israel: Coalition Instability and Governance Crisis

Israel’s scheduled October 27, 2026, election reflects the dramatic collapse of the 2022-2024 national unity government that Netanyahu had assembled in the aftermath of Hamas’s October 7, 2023, attack.

The government fractured over disagreements regarding Gaza strategy, post-war planning, and exemptions for ultra-Orthodox Israelis from mandatory military service. Netanyahu’s coalition lost its parliamentary majority in July 2025 when the far-right Otzma Yehudit party left the government over a ceasefire agreement. However, the party later rejoined after the ceasefire collapsed.

The election’s timing remains uncertain. Under Israeli electoral law, if the government fails to pass a budget by March 31, 2026, elections are automatically triggered. Otherwise, elections must be held by October 27.

Netanyahu, sensing vulnerability in current polling, has asked aides to prepare for early polls, possibly in June 2026, a move that would allow him to frame the election around security and military performance rather than around his criminal trials.

Current polling presents a complex picture for Netanyahu. His Likud party polls at 24-28 seats (down from 32 currently held), while Benny Gantz’s Bennett Bloc aggregates 57-61 seats across multiple parties. The opposition remains fragmented, with Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid polling at 10-20 seats, but Gantz emerges as the clearest alternative to Netanyahu’s continued leadership.

Netanyahu personally faces four criminal trials involving charges of breach of trust, bribery, and fraud, which will continue to generate negative publicity as the election campaign unfolds.

Beyond domestic Israeli politics, the October 2026 election carries enormous regional implications. The outcome will determine whether Netanyahu can form a government and, if so, under what coalition constraints. A Bennett-led government would likely pursue a more pragmatic approach to Palestinian governance and regional relations.

A renewed Netanyahu government might pursue more assertive regional policies toward Iran, Syria, and Palestinian areas, potentially triggering escalation with Hezbollah in Lebanon or other regional actors. The election’s outcome will also influence whether Israel continues to shift toward deeper alignment with Gulf Arab states (the Abraham Accords framework) or reorients toward a more confrontational regional posture.

United States: Midterm Reckoning in Polarized Democracy

The November 3, 2026, U.S. midterm elections represent a critical test of American democratic resilience amid profound institutional stress.

All 435 House seats, 35 of 100 Senate seats, and 39 gubernatorial positions will be contested.

Historically, the president’s party loses House seats in midterm elections; the average loss over the past fifteen cycles has been twenty-four seats. Republicans currently hold a slim seven-seat House majority (220-213), making them vulnerable to losses that would flip the chamber to Democratic control.

President Donald Trump, confronting the prospect of losing the House for the second time in his presidency (an outcome that preceded impeachments in his first term), has begun an aggressive gerrymandering campaign, pushing Republican-controlled states (Texas, Missouri, North Carolina) to redraw their electoral maps to maximize Republican seats.

Meanwhile, Democratic-controlled states are pursuing similar strategies, creating a chaotic partisan scramble to engineer electoral advantage before voters cast ballots.

This institutional manipulation reflects a deeper pathology: both major parties have lost faith in the legitimacy of neutral election administration and instead view elections primarily as contests to be won through procedural manipulation rather than persuasion.

Public mood is darkly pessimistic. Approximately 60 percent of Americans say the country is headed in the wrong direction, and economic anxiety runs high amid an affordability crisis (rising living costs, stagnating wages, fears of AI-driven unemployment).

Both parties are internally divided over message strategies, with Republicans grappling with Trump’s continued dominance and Democrats uncertain whether to embrace progressive social policies or pivot toward moderate economic messaging.

The midterm elections carry outsized geopolitical significance beyond their U.S. domestic implications.

If Democrats retake the House, it will complicate Trump’s second-term agenda on trade policy (particularly regarding China and tariffs), immigration enforcement, and confrontation with Iran.

If Republicans retain control, they will have greater freedom to pursue more assertive foreign policies, potentially including military strikes against Venezuela or other adversaries.

The election will also signal whether the American electorate has grown weary of Trump’s style and politics or whether his coalition has consolidated into a durable majority capable of sustaining GOP dominance across electoral cycles.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: Structural Drivers of Democratic Crisis

These ten elections do not occur in isolation but rather reflect common underlying pathologies affecting democratic systems globally.

The most significant of these is the erosion of the separation of powers and the concentration of executive authority.

In Hungary, Orbán has subordinated the judiciary and media to political control; in Ethiopia, Abiy has used emergency powers to restrict civil liberties and opposition activity; in Israel, Netanyahu has attempted judicial reform to shield himself from prosecution; in Brazil, the judiciary has wielded extraordinary power to bar Bolsonaro from candidacy; in the U.S., Trump is restructuring the executive branch to consolidate power and eliminate independent agencies.

A second structural driver is the rise of right-wing populism and anti-establishment politics. From the Sweden Democrats (20+ percent support) to Abelardo de la Espriella in Colombia to Hungary’s Tisza Party (representing a populist challenge to Orbán), voters across regions and income levels are rejecting mainstream political establishments and embracing figures promising to overturn existing arrangements.

This pattern reflects genuine sources of voter grievance—economic inequality, joblessness (particularly youth unemployment), migration pressures, and the perceived irrelevance of traditional institutions to citizens’ daily lives—but also represents a dangerous opening for authoritarian figures who campaign as populist outsiders and then consolidate power once in office.

A third structural factor is the correlation between electoral contests and conflict dynamics. In Ethiopia, Israel, Armenia, and Colombia, elections occur within contexts of active warfare, insurgency, or political violence. These security conditions fundamentally constrain the possibility of free and fair electoral competition, as voters cannot safely campaign or cast ballots in conflict-affected areas.

Moreover, incumbents facing electoral vulnerability have an incentive to manufacture national security emergencies to justify authoritarian measures and rally nationalist support.

The possibility of renewed conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea, the continuation of violence in Colombian rural areas, and Israel’s ongoing confrontation with Hamas and Hezbollah all create conditions where elections become vehicles for ratifying security policies rather than genuine competitions over governance approaches.

A fourth structural factor is the role of great power competition in electoral outcomes. China and Russia are investing heavily in information warfare, disinformation campaigns, and cyber operations to influence electoral outcomes in their strategic interest zones.

Sweden’s vulnerability to Russian election interference, Armenia’s precarious position amid U.S.-Russia competition for regional influence, and Bangladesh’s strategic importance to India's security interests all suggest that external actors will seek to shape electoral dynamics in line with their strategic preferences.

The Trump administration’s announcement of a planned April 2026 summit between Trump and Xi Jinping has implications for electoral campaigns in U.S. ally nations, as adversaries calculate whether confrontation or cooperation with Washington will characterize the next eighteen months.

A fifth structural factor is the weakening of political parties as institutions. Across the electoral calendar, traditional parties are losing the capacity to aggregate interests, transmit information, or organize constituencies. Outsider candidates (from Péter Magyar in Hungary to Abelardo de la Espriella in Colombia to the National Citizens Party in Bangladesh) are emerging to challenge established parties.

In the U.S., both the Republican and Democratic parties are internally fractured, with intra-party conflicts rivaling inter-party competition in intensity. This institutional weakness makes political outcomes more volatile and unpredictable, as no party possesses a commanding organizational capacity to discipline its members or ensure electoral consistency.

Future Trajectories: Scenarios and Implications

The aggregate outcomes of 2026’s elections will produce one of three broad scenarios, each carrying distinct implications for global governance, conflict, and democratic resilience. The most optimistic scenario would involve genuine competitive elections producing meaningful leadership transitions and renewed mandates for democratic reform.

First scenerio

In this scenario, Bangladesh’s electorate would reject authoritarian temptations and establish inclusive governance norms; Hungary’s voters would punish Orbán despite gerrymandering; Colombia would sustain Cepeda and progressive governance; Ethiopia would replace autocratic rule; Armenia would consolidate peace; Sweden would reinforce democratic norms despite populist pressure; Brazil would maintain democratic continuity; Israel would transition to new leadership; U.S. voters would prevent further democratic erosion; and The Gambia would reject Barrow’s term-limit circumvention. In this optimistic scenario, 2026 would mark the beginning of a democratic recovery and renewed commitment to institutional constraints on executive power.

Second scenerio

A second, more pessimistic scenario would involve the consolidation of authoritarian or quasi-authoritarian governance despite electoral contests. In this scenario, Yunus and the interim government in Bangladesh would convert their temporary authority into durable political control; Hungary’s Orbán would prove that institutional engineering can indefinitely sustain electoral dominance; Colombia would revert to conservative governance at Petro’s expense; Ethiopia’s elections would transparently rubber-stamp Abiy’s continued rule; Armenia would remain locked in unresolved conflict despite peace gestures; Sweden would drift rightward as populism consolidated; Brazil would experience chronic political instability; Netanyahu would navigate election and court challenges to remain prime minister; the Trump administration would consolidate Republican House control through gerrymandering; and Barrow would secure a controversial third term.

In this scenario, 2026 would mark the acceleration of democratic backsliding and the normalization of electoral manipulation as a governance tool.

Third scenerio

A third scenario, the most volatile, would involve electoral shocks and unpredictable outcomes that destabilize regional orders and create openings for significant power intervention.

In this scenario, Bangladesh’s election could trigger communal violence; Hungary’s result could trigger EU sanctions or withdrawal; Colombia’s election could be overshadowed by escalating gang violence; Ethiopia’s election could precipitate renewed war with Eritrea and regional conflict; Armenia could face renewed war with Azerbaijan; Sweden could see coalition negotiations collapse into instability; Brazil could experience unexpected rightward shift toward Bolsonarist factions; Israel could see early elections trigger coalition chaos; the U.S. could see dramatic House-control reversal; and The Gambia could experience post-election violence. In this volatile scenario, 2026 would become a year of geopolitical instability comparable to the 1930s or 1989, with cascading surprises producing unpredictable realignments in global order.

The likely outcome will consist of elements from all three scenarios, varying by region and political context. Democratic resilience will prove more decisive in established democracies like Sweden and the United States, where institutional checks and independent media retain significant capacity to constrain executive overreach.

Democratic backsliding will likely accelerate in weaker states like Ethiopia, where security conditions and state capacity render genuine competitive contestation impossible.

The intermediate cases—Bangladesh, Hungary, Colombia, Armenia, Brazil, Israel, and The Gambia—will produce mixed outcomes, with some elections delivering genuine transitions. In contrast, others formalize elite circulation without addressing underlying institutional crises.

Conclusion

Democratic Erosion in the Twenty-First Century: A Comparative Analysis of Institutional Collapse, Electoral Manipulation, and Opposition Fragmentation Across Ten 2026 Elections

The year 2026 will be remembered as a consequential inflection point in the trajectory of global democracy and international order.

The ten elections scheduled across the calendar represent not merely routine electoral cycles but fundamental choices about governance systems, national identities, and regional alignments. The results will determine whether the 2010s and 2020s prove to be a temporary moment of democratic recession followed by renewal, or the opening phase of a longer-term democratic collapse comparable to the 1930s.

The central tension animating these elections is the gap between the legitimacy that democratic forms provide and the institutional erosion that permits authoritarian substance.

Across these ten contests, rulers and challengers alike will campaign as democrats while working to constrain democratic competition, to manipulate electoral rules, and to accumulate discretionary power. Voters will confront politicians promising solutions to economic inequality, joblessness, insecurity, and corruption, yet lacking the institutional capacity or political will to deliver tangible improvements.

The outcomes of 2026’s elections will reverberate for years to come. They will determine whether the international order remains anchored in American strategic leadership or whether great-power competition between Washington and Beijing becomes more assertive and destabilizing.

They will determine whether regional conflicts (Ukraine, Gaza, Armenia-Azerbaijan tensions) move toward negotiated resolution or toward escalation and expansion. They will decide whether populist movements remain contained within democratic institutions or accelerate the breakdown of institutions and the rise of authoritarianism.

For policymakers, investors, and citizens monitoring global developments, 2026 demands focused attention. The elections are not side events in an otherwise stable global system, but rather the primary mechanism through which the international order will be reorganized. Those decisions will shape the character of global governance, the distribution of power across regions, and the prospects for human freedom and dignity in the decades ahead.

The stakes could scarcely be higher, the outcomes more uncertain, or the moment more consequential for the future of democratic governance worldwide.