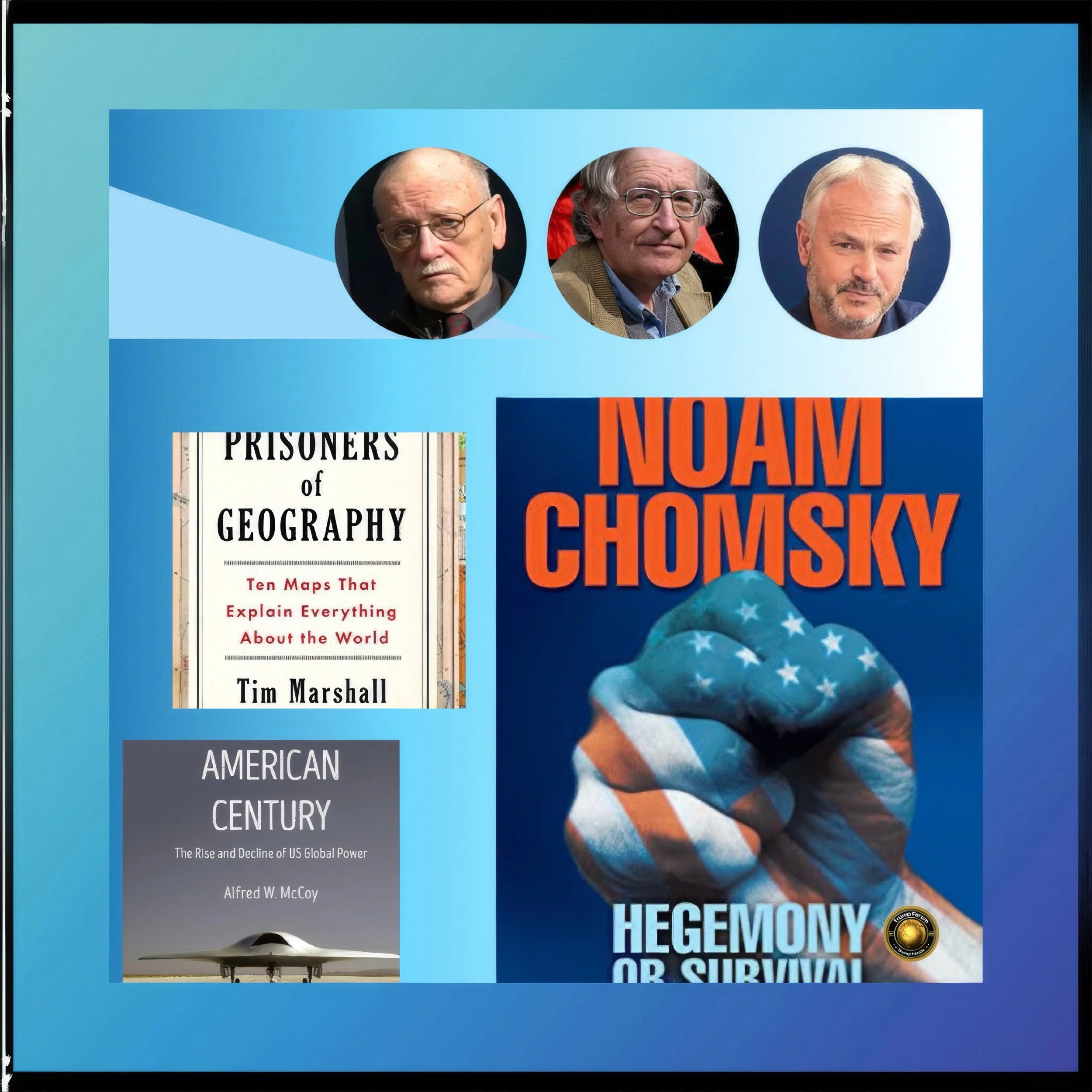

How America Squandered Its Unipolar Moment: The Rise and Fall of Hegemonic Benevolence

Introduction

The end of the Cold War gave the United States an unprecedented opportunity to reshape the global order according to its values and interests.

This “unipolar moment,” as Charles Krauthammer termed it in 1990, represented a unique historical configuration where one nation possessed such overwhelming power that it could effectively govern the international system.

However, rather than institutionalizing a durable liberal international order, America chose to rely on what can be termed “hegemonic benevolence” - the belief that its dominant position, combined with generally beneficent intentions, would be sufficient to maintain global stability and cooperation.

FAF analyzes the approach, which ultimately proves unsustainable. It led to the gradual erosion of American credibility, the emergence of rival powers, and the fragmentation of the very order the United States had sought to create.

The fundamental contradiction at the heart of American strategy was attempting to build a universal liberal order while maintaining hegemonic control.

This created tensions that eventually undermined American leadership and global institutional cooperation.

The Genesis and Nature of American Unipolarity

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 created what Krauthammer described as an unprecedented “gap in power between the leading nation and all the others.”

This unipolar structure fundamentally differed from previous international systems, as no historical precedent existed for such concentrated global power.

As Paul Kennedy later acknowledged, “Nothing has ever existed like this disparity of power; nothing. Charlemagne’s empire was merely Western European in its reach.

The Roman empire stretched farther afield, but there was another great empire in Persia and a larger one in China”.

The United States emerged from the Cold War not merely as the victor in an ideological struggle but as the sole global superpower capable of projecting military, economic, and cultural influence anywhere in the world.

The Gulf War 1991 provided the first demonstration of this unipolar power in action.

The conflict revealed that only the United States possessed the diplomatic, military, economic, and political tools necessary to marshal a global coalition and project force decisively in any region.

The war’s swift conclusion with minimal casualties demonstrated American technological superiority and operational capabilities that no other nation could match.

This military triumph also exposed what Krauthammer called the “superficial” nature of multilateralism in the new order - while other nations participated in the coalition, absolute decision-making authority remained concentrated in Washington.

The unipolar moment was characterized by American military dominance and the broader appeal of American values and institutions.

Following the Cold War, former Warsaw Pact countries were “attracted by the consumerist wave triggered by America,” the United States became “the model: unchallengeable, unmatched, uncontrollable.”

This cultural hegemony complemented military and economic supremacy, creating what appeared to be a stable foundation for American global leadership.

However, this concentration of power also created expectations that America would use its position responsibly and in ways that benefited the broader international community.

The Contradictions of Hegemonic Benevolence

The concept of “hegemonic benevolence” became central to how American policymakers and scholars understood the post-Cold War order.

This notion suggested that American hegemony fundamentally differed from previous forms of imperial dominance.

It was motivated by self-interest and a commitment to universal principles of liberty, democracy, and human rights.

The idea was rooted in American exceptionalism - the belief that the United States was “an extraordinary nation with a special role to play in human history; not unique but also superior among nations.”

From this perspective, American actions were inherently benevolent because they were dedicated to “principles of liberty and freedom for all humankind.”

However, this benevolent self-conception created fundamental tensions in practice.

While the United States proclaimed its commitment to building a liberal international order based on institutions and rules, it consistently prioritized maintaining its dominance and freedom of action.

The Clinton administration’s approach to NATO expansion exemplified this contradiction.

While expansion was justified as promoting European integration and democratic consolidation, it “cemented America’s positions in Europe, as NATO revolved around the United States.”

When faced with supporting the European Union as an independent defense actor, “the Clinton administration balked because it was worried about losing influence.”

This pattern of using institutional frameworks to maintain American control rather than genuinely sharing power characterized much of the post-Cold War order.

One analysis notes that “benevolent hegemony refers to the stable international order underpinned by a hegemon who provides essential public goods for the general interest of the international society.”

Yet the provision of these “public goods” was always conditional on maintaining American prerogatives and advancing American interests.

The result was what critics described as an order that appeared multilateral on the surface but remained fundamentally unilateral in its decision-making structures.

The limitations of benevolent hegemony became particularly apparent when American interests diverged from broader international preferences.

The United States expected other nations to support its initiatives and accept its leadership but was reluctant to submit to genuine constraints or shared authority.

This created resentment among allies and allowed rivals to challenge American legitimacy by pointing to the gap between American rhetoric and behavior.

The Erosion of Institutional Foundations

One of the most significant failures of American strategy during the unipolar moment was the choice to prioritize hegemonic control over institutional development.

Unlike the post-World War II period, when the United States invested heavily in creating multilateral institutions like the United Nations, NATO, and the Bretton Woods system, the post-Cold War approach was more ad hoc and unilateral.

While these earlier institutions had been designed to “tie the United States more closely to its postwar partners, reducing worries about domination and abandonment,” the post-Cold War order lacked comparable institutional anchors.

The September 11 attacks marked a critical turning point in this regard, as “U.S. unilateralism was unleashed.”

The Bush administration’s approach was heavily influenced by neoconservative thinking that “believed the way to do so was unilaterally through U.S. hard power.”

Rather than working through existing multilateral frameworks, the United States increasingly acted outside institutional constraints, justifying its actions through appeals to its hegemonic benevolence and superior capabilities.

The invasion of Iraq, in particular, “served to make a mockery of the conceptions of a rules-based international order and greatly eroded global trust in U.S. hegemony.”

This erosion of institutional foundations had several consequences.

First, it reduced the legitimacy of American leadership by demonstrating that the United States would abandon multilateral processes when they proved inconvenient.

Second, it created space for rival powers to challenge American hegemony by offering alternative institutional frameworks.

China, in particular, “seized the moment, expanding its economic engagement with the global south” and making “global institutions a tough way to advance a more liberal world.”

Third, it undermined American credibility in multilateral forums, where “U.S. hypocrisy was used as a cudgel and prompted the United States to engage less.”

The Obama administration attempted to restore American commitment to multilateral institutions, but this effort was hampered by the damage already done to American credibility.

Obama’s “unwillingness to use direct force against Syria’s Assad regime for its use of chemical weapons” was interpreted as a sign that “the United States would not instinctively hold up the world order even when a critical norm was at stake.”

While this restraint was intended to demonstrate American learning from the Iraq debacle, it instead reinforced perceptions of declining American commitment to the order it had created.

The Financial Crisis and Domestic Rejection

The 2008 financial crisis represented a watershed moment in the decline of American hegemonic benevolence.

The crisis “created a sense of U.S. decline and punctured the sense of liberalism’s inevitability.”

More importantly, it revealed the fragility of the liberal international order's economic foundations and raised questions about American competence and leadership.

While the crisis “ultimately did not turn the world against the U.S.-led liberal economic order,” it had the paradoxical effect of turning “Americans against it.”

This domestic rejection of the international order was perhaps the most significant challenge to American hegemonic benevolence.

The Republican-led Senate’s rejection of the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2016, followed by opposition from both the Trump and Biden administrations to the World Trade Organization, demonstrated that “the United States had turned against the main thrust of its own limited post-Cold War order-building.”

This internal opposition made it impossible to sustain the kind of “hyper-engagement” that hegemonic benevolence required.

The rise of populist movements in the United States reflected broader dissatisfaction with the costs and consequences of maintaining global hegemony.

Many Americans, particularly those who had served in post-9/11 conflicts, turned “not against the war itself but against the liberalism used to justify waging it, along with the notion of using U.S. power and leadership to further a liberal world.”

This domestic backlash made it politically difficult for any administration to maintain the level of international engagement that hegemonic benevolence demanded.

The Trump administration’s explicit rejection of multilateral commitments represented the culmination of this domestic opposition.

Trump’s unilateralist approach, including tariffs on allies and adversaries, effectively dismantled many institutional arrangements supporting American hegemony.

His vision of “America First” explicitly rejected the notion that American leadership should serve broader global interests, instead embracing a transactional approach to international relations.

The Impossibility of Sustaining Benevolent Hegemony

The ultimate failure of hegemonic benevolence lies in its inherent contradictions and unsustainable demands.

Maintaining global hegemony required enormous resources, sustained domestic political support, and consistent demonstration of benevolent intentions.

However, maintaining hegemony often required actions that undermined perceptions of benevolence.

Military force, economic coercion, and political pressure to maintain American dominance inevitably created resentment and resistance among allies and adversaries.

Furthermore, hegemonic benevolence placed impossible expectations on American decision-makers.

They were expected to act as global policemen while respecting the sovereignty of other nations, to promote democracy while maintaining strategic relationships with authoritarian allies, and to provide international public goods while ensuring American interests were protected.

These contradictory demands made it virtually impossible to maintain the legitimacy that benevolent hegemony required.

The concept of benevolence itself proved problematic in practice. Recent scholarship notes that “benevolence can mask paternalism, especially when one party denies the agency or identity of the other.”

American efforts to promote democracy and human rights, while often well-intentioned, were frequently perceived as attempts to impose American values and institutions on unwilling populations.

The selective application of these principles reinforced this perception, as the United States often prioritized strategic relationships over democratic values.

The rise of China as a potential rival hegemon further exposed the limitations of American benevolent hegemony.

China’s approach to international relations, emphasizing economic development and non-interference in domestic affairs, offered an alternative model many developing countries found attractive.

While China’s approach had limitations and contradictions, it demonstrated that American hegemonic benevolence was not the only possible foundation for international order.

Conclusion

The failure of America’s unipolar moment represents one of the most significant missed opportunities in modern international relations.

At the end of the Cold War, the United States possessed unprecedented power and global legitimacy, creating conditions that could have supported the development of a truly multilateral liberal international order.

Instead, America chose to rely on hegemonic benevolence, believing that its dominant position and good intentions would be sufficient to maintain global stability and cooperation.

This approach proved unsustainable for several interconnected reasons.

The contradictions inherent in benevolent hegemony made it impossible to maintain legitimacy over time, as American actions inevitably fell short of the high standards that benevolence implied.

The preference for maintaining hegemonic control over building robust institutions left the order vulnerable to American domestic political changes and the rise of rival powers.

The enormous costs of global hegemony in terms of resources and domestic political capital eventually exceeded American willingness to pay them.

The lessons of this failure extend beyond American foreign policy to broader questions about international order and global governance.

The experience suggests that sustainable international orders require genuine institutionalization and shared authority rather than relying on the benevolence of a single dominant power.

While hegemonic leadership may be necessary to establish international order, the long-term stability of such order depends on creating institutions and norms that can function independently of hegemonic power.

Contemporary policymakers must learn from America’s failed unipolar moment and work toward building more durable and legitimate forms of international cooperation that can withstand changes in global power distribution.