Tito’s Ghost in the Age of Multipolarity: Which Modern Leader Can Balance Ethnic Pluralism with Strategic Independence - Part VI

Executive Summary

Josip Broz Tito’s governance paradigm—synthesizing revolutionary charisma, transcending ethnic particularism, non-aligned strategic independence, rejecting Cold War bipolarism, and decentralized socialist self-management, granting ethnic regions autonomy whilst preserving federal cohesion—remains conspicuously absent from contemporary geopolitical leadership. Yet, his template proves disturbingly relevant as multipolarity fragments ostensibly unitary states across Eurasia and Africa.

No extant leader fully replicates Tito’s multifaceted approach; however, Xi Jinping’s “civilizational state” ideology, Abiy Ahmed’s “Medemer” unity vision, and Vladimir Putin’s “multiethnic civilization” rhetoric partially echo Tito’s emphasis on transcending ethnic nationalism through supranational frameworks.

Critically, all three leaders diverge from Tito’s foundational commitment to genuine independence from hegemonic blocs, with Xi and Putin instead constructing alternate spheres of influence, whilst Abiy struggles with state capacity to maintain federal coherence.

This analysis examines how contemporary autocrats invoke Tito’s vocabulary of multiethnic unity whilst abandoning his material conditions—decentralized institutions, revolutionary legitimacy, and genuine neutrality—rendering their federations vulnerable to recursive ethnic fragmentation precisely as Yugoslavia dissolved.

The imperative for global stability demands identifying leaders capable of synthesizing Tito’s institutional innovations with transparent democratic mechanisms and enforceable minority protections, forestalling cascading dissolutions resembling Yugoslav patterns across Ukraine, Ethiopia, Myanmar, and other ethnically heterogeneous polities.

Introduction

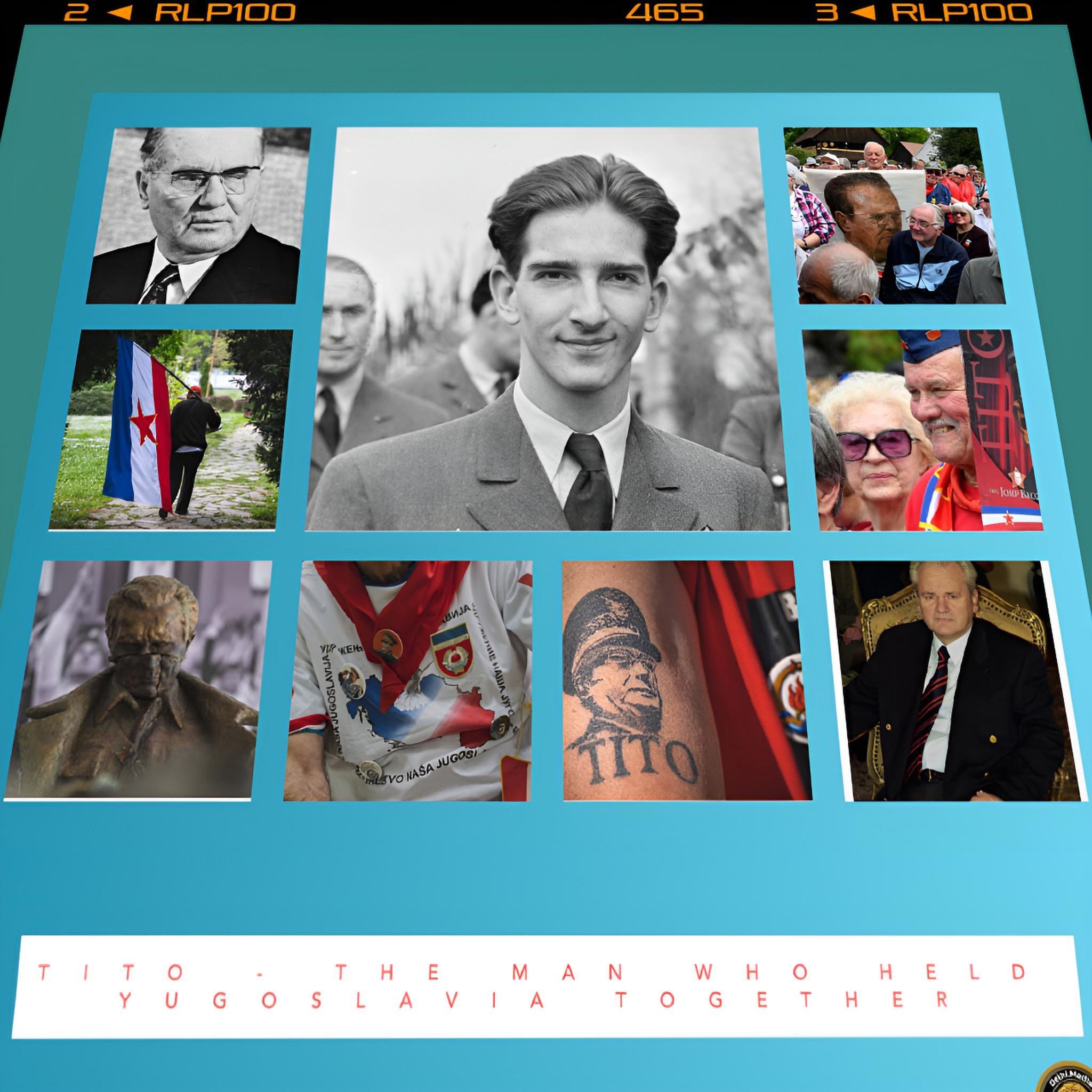

Tito’s Yugoslavia represents a singular historical achievement: the preservation of a six-republic, two-autonomous-province, multiethnic socialist federation for thirty-five years (1945–1980) despite lacking the prerequisites typically deemed essential for state stability.

The federation encompassed Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Bosniaks, Macedonians, Montenegrins, plus substantial Kosovar-Albanian and Vojvodinian-Hungarian minorities—groups whose historical antagonisms, intensified by interwar centralization, World War II genocides, and territorial disputes, would ordinarily have precipitated perpetual fragmentation.

Yet Tito achieved stability through a tripartite architectural model: revolutionary legitimacy transcending ethnic identity through the Partisan movement’s anti-fascist credentials; non-aligned strategic positioning that rendered external alignment costlier than internal compromise; and institutional decentralization through workers’ self-management councils granting ethnic regions substantive autonomy whilst preserving federal prerogatives.

The 1974 Constitution crystallized this framework, devolving extraordinary autonomy to constituent republics and autonomous provinces whilst maintaining party unity through the League of Communists’ centralized cadre structure.

Upon Tito’s death in 1980, this institutional arrangement proved unsustainable without charismatic central authority, federal economic coherence, and supranational ideological legitimacy—all of which dissipated during the 1980s debt crisis and the global delegitimization of communism.

Contemporary geopolitical leaders confront analogous challenges: managing multiethnic federations amid economic volatility, great-power competition, and resurgent ethno-nationalisms that threaten centrifugal fragmentation.

Xi Jinping, Abiy Ahmed, and Vladimir Putin—each leading multiethnic polities—consciously invoke Titoist vocabulary of “unity transcending ethnicity” whilst constructing fundamentally distinct institutional and ideological frameworks.

Understanding where these leaders’ models converge with and diverge from Tito’s template illuminates both contemporary vulnerability to Yugoslav-style dissolution and potential pathways toward multiethnic stability.

Tito’s Leadership Model: The Synthesis and Its Foundations

Josip Broz Tito’s legitimacy rested fundamentally upon his role as Supreme Commander of the Partisan movement (1941–1945), a genuinely multiethnic anti-fascist coalition comprising Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, and Bosniaks unified against Axis occupation and collaborationist regimes (Ustaše, Serbian Chetnik militias).

The Partisan victory transcended ethnic identity through revolutionary praxis: Serbs fought alongside Croats to eliminate the genocidal Ustaše apparatus; Croats and Slovenes recognised Serb grievances from Ottoman-era subjugation.

This shared wartime sacrifice against external occupation provided Tito with revolutionary legitimacy—distinct from ethnic nationalism—that could plausibly claim to represent the liberation of all South Slavic peoples from imperialism.

The “Brotherhood and Unity” slogan that animated postwar Yugoslavia derived not from abstract cosmopolitanism but from concrete historical experience wherein ethnic cooperation proved necessary for national liberation.

Tito’s 1948 break with Stalin constituted the second pillar of his legitimacy. Unlike other Eastern European communist parties, which were entirely dependent on Soviet military occupation and ideological validation, Tito’s party possessed genuine domestic support and an indigenous army. It demonstrated the capacity to resist Soviet demands.

The Cominform expulsion threatened Yugoslavia’s survival; responding through “workers’ self-management” and market-socialist liberalisation, Tito positioned Yugoslavia as a third path between Soviet bureaucratic centralism and Western capitalism.

This independent stance—neither American-aligned nor Soviet-dominated—rendered Yugoslavia strategically valuable to both blocs, enabling substantial economic aid from Western governments and institutions, capital imports exceeding those of other Soviet-bloc nations, and freedom from Soviet-style collectivization.

Non-alignment became institutionalised through the Non-Aligned Movement, which Tito cofounded in 1956, positioning Yugoslavia as a champion of developing nations’ independence from great-power domination.

The 1974 Constitution represented Tito’s institutional answer to multiethnic management: rather than centralized Serbian hegemony or ethnic partition, the document created an extraordinary federal structure wherein six republics and two autonomous provinces possessed quasi-sovereign prerogatives over taxation, policing, education, language, and cultural affairs, whilst the federal centre retained defence, foreign policy, and inter-republican dispute resolution.

The League of Communists, operating through centralized party discipline, preserved federal unity by preventing any single republic’s communist leadership from advancing ethnic nationalist agendas.

Crucially, this institution functioned because the party itself transcended ethnicity—communist ideology, however nominal, provided legitimacy independent of ethnic identity. Tito’s cult of personality—images of “Marshal Tito” adorning public spaces, his symbolic unity of Partisans and ethnicities—reinforced this supranational framework, rendering his authority above ethnic competition.

Xi Jinping’s “Civilisational State” and the Limits of Authoritarian Multiethnic Management

Xi Jinping’s China confronts the most substantial multiethnic management challenge of any contemporary power, encompassing a Han majority comprising roughly 92% of the population alongside fifty-five officially recognised ethnic minorities, including Tibetan, Uyghur, Mongolian, and Hui Muslims.

Xi’s governance model invokes explicitly Titoist language of transcending ethnic nationalism through a supranational framework—in this instance, the concept of a “civilizational state” rooted in “Great Unity” (Da Yitong), an ancient Chinese imperial notion of unified territory under Han cultural hegemony.

Xi’s rhetoric echoes Tito’s anti-hegemonic positioning. China presents itself as a unique civilizational path, neither Western liberal capitalism nor Soviet Marxism, but rather Sino-Confucian governance transcending Western individualism and Russian authoritarianism.

The Belt and Road Initiative, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and BRICS expansion serve analogous functions to Yugoslavia’s Non-Aligned Movement—positioning China as leader of a third bloc purportedly independent from American hegemony.

Like Tito, Xi emphasises party unity transcending regional particularism, maintaining centralized Communist Party control over regional governments and preventing provincial nationalism.

However, Xi’s model diverges catastrophically from Tito’s template in three critical dimensions.

First, whilst Tito genuinely devolved institutional power to republics through workers’ councils, Xi has consolidated centralized control, reversing decades of provincial autonomy and stripping local governments of fiscal and administrative authority.

The 2012–2017 consolidation of Xi’s power (elimination of term limits in 2018, purges of party rivals, centralisation of finance and security apparatus) represents precisely the opposite institutional trajectory from Tito’s decentralisation.

Regional autonomy that Tito viewed as compatible with federal unity, Xi treats as a secessionist threat requiring containment.

Second, Xi’s “civilisational state” concept privileges Han cultural and linguistic hegemony explicitly, contrasting with Tito’s revolutionary transcendence of ethnic identity.

Recent ideological and policy shifts emphasise Mandarin and Han norms as the civilisational core, and a broader Sinicisation campaign has targeted minority languages, religions, and customs in Xinjiang, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia, institutionalising ethnic hierarchy rather than multiethnic equality.

Tito suppressed all ethnic nationalisms relatively evenly; Xi privileges Han nationalism under the guise of civilisational continuity, generating Uyghur and Tibetan resentments broadly analogous to Kosovo Albanians’ grievances against perceived Serb hegemony within late socialist Yugoslavia.

Third, Xi’s civilisational state model serves as justification for active great-power competition against Western hegemony and American alliance systems.

Xi, unlike Tito, explicitly constructs Sino-Russian alignment against NATO expansion, AUKUS submarine partnerships, and American technological dominance. This bloc-building contradicts non-alignment; China and Russia are constructing an alternate hierarchical order rather than genuinely neutral multipolarity.

Contemporary geopolitical volatility—risk of US–China military conflict over Taiwan, intensifying strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific, and controversies over Belt and Road debt and infrastructure control—derives in part from this assertive posture, distinct from Tito’s doctrine of peaceful coexistence and strategic balancing.

The implications for Chinese multiethnic stability are grave: lacking Tito’s decentralized institutions and genuine revolutionary legitimacy transcending ethnicity, Xi’s civilisational state framework depends heavily upon the party’s coercive capacity.

Mass surveillance systems and “re-education” campaigns in Xinjiang, tighter controls in Tibet, and restrictions on Mongolian-language education represent the opposite of Titoist multiethnic accommodation.

Should the Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy erode—through economic crisis, military defeat, or demographic shifts—the absence of institutionalised multiethnic accommodation mechanisms makes cascade ethnic fragmentation a plausible risk, with Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia exhibiting secessionist potential analogous to Yugoslav republics circa 1991.

Abiy Ahmed’s “Medemer” and Ethiopia’s Fraught Unity Experiment

Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who assumed office in 2018, explicitly articulated a Tito-adjacent vision termed “Medemer” (addition, togetherness, or synergy), intended to transcend the ethnic federalism institutionalised by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) regime (1991–2018).

The EPRDF had deliberately restructured Ethiopia along ethnic lines, creating ethnically demarcated regions (Oromia, Amhara, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region, Tigray, and others) with substantial autonomy—an institutional framework that mirrored some features of Tito’s 1974 Constitution but without a centralised party apparatus capable of fully subordinating ethnic nationalism to a supranational project.

Abiy’s biography embodies Titoist symbolism. The son of an Orthodox Christian Amhara father and Muslim Oromo mother, his mixed ethno-religious parentage ostensibly positioned him as a supranational arbiter capable of transcending Amhara–Oromo–Tigray antagonisms that had produced recurring territorial disputes, resource conflicts, and episodes of mass violence in modern Ethiopian history.

Upon assuming office, Abiy released political prisoners, loosened media controls, and articulated a vision of “coming together” that sought to reframe identity around national unity without formally abolishing ethnic federal structures.

His 2019 Nobel Peace Prize, awarded for resolving the long-standing border conflict with Eritrea, appeared to vindicate this unity narrative in the eyes of international observers, echoing the global recognition that Tito enjoyed as a leader of non-aligned states.

However, Abiy’s institutional capacity to deliver Medemer proved vastly inferior to Tito’s revolutionary party machinery. The EPRDF, while authoritarian, had maintained ethnic federalism within a relatively disciplined party structure that constrained overt communal warfare during the 1990s–2010s.

Abiy’s attempt to recentralise authority and rebrand the ruling coalition as the Prosperity Party, while simultaneously widening political space, created an institutional vacuum: as regional autonomy appeared under threat and central authority reasserted itself, ethnic elites mobilised constituencies to defend territorial and political prerogatives.

The Tigray War (2020–2022)—which involved federal forces, Eritrean troops, and regional militias—resulted in catastrophic human losses, with some estimates suggesting around 600,000 deaths, alongside mass displacement and atrocities widely described as amounting to crimes against humanity or genocide.

This outcome directly contradicted Medemer’s unity narrative, exposing the weakness of charismatic leadership unaccompanied by robust institutional mechanisms for multiethnic accommodation and dispute resolution.

Critically, Abiy lacked Tito’s two foundational advantages: revolutionary legitimacy transcending ethnicity (Abiy rose through the EPRDF’s security structures rather than an independent anti-colonial struggle) and independent geopolitical positioning (Ethiopia remains entangled with Western and Chinese economic and security partners, without Yugoslavia’s degree of non-aligned leverage).

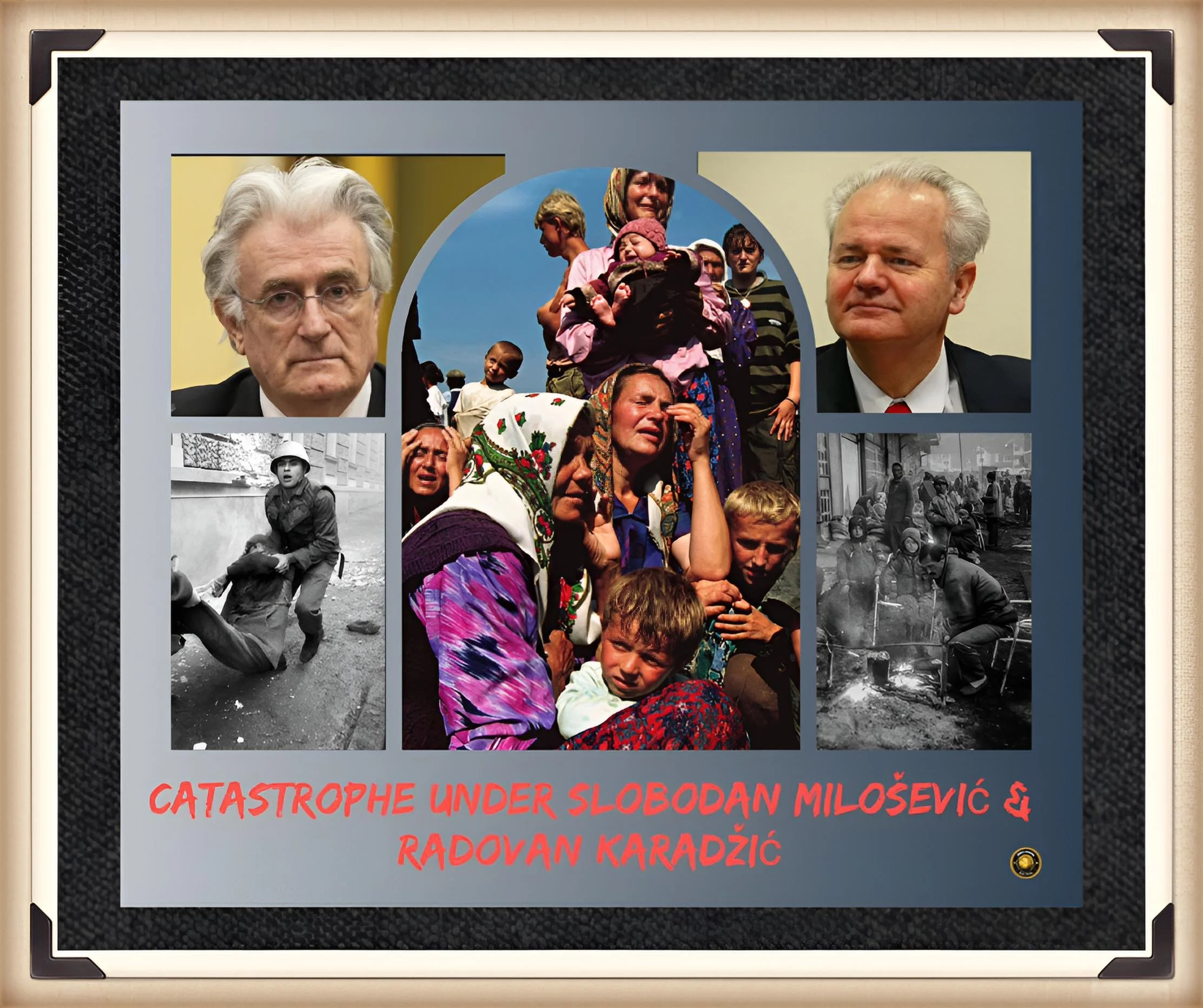

The Tigray War revealed that Abiy’s authority rested on the coercive capacity of the federal security apparatus, itself shaped by ethno-regional dynamics, making him dependent on shifting ethnic coalitions rather than a supranational ideology. When Tigray’s leadership resisted federal restructuring, Abiy possessed few institutional tools short of force, paralleling the logic by which Slobodan Milošević turned to ethnic mobilisation and paramilitaries as Yugoslavia unravelled.

Abiy’s trajectory illuminates the insufficiency of Titoist rhetoric absent Titoist institutions: unity visions, cross-ethnic biography, and international accolades cannot substitute for decentralised federal institutions, a party or constitutional framework transcending ethnicity, and genuine strategic autonomy from external patrons.

Ethiopia’s current tentative stabilisation—following ceasefire agreements and African Union–facilitated talks—remains vulnerable to renewed fragmentation should central authority weaken further or economic distress intensify inter-ethnic competition.

Vladimir Putin’s “Multiethnic Civilisation” and Russian Sphere-of-Influence Imperialism

Vladimir Putin’s governance framework most explicitly invokes Titoist multiethnic management principles, articulated through the idea of Russia as a “multiethnic civilisation” with Russian culture at its core rather than as a narrowly defined ethnic nation-state.

This formulation, advanced in speeches to bodies such as the Council for Interethnic Relations and the Valdai Discussion Club, rejects open ethnic Russian chauvinism in favour of a broader civilisational identity grounded in Russian language, Orthodox Christianity, and shared historical narratives.

Putin’s 2020 constitutional amendments, which describe Russian as the language of the “state-forming people,” codify a vision in which Russian culture is foundational yet formally compatible with the rights of numerous ethnic minorities, from Tatars and Bashkirs to Chechens and others.

This rhetorical stance echoes Tito’s “Brotherhood and Unity,” positioning the state as transcending ethnic nationalism through a supranational civilisational frame. Putin’s emphasis on “traditional values,” family, and opposition to Western liberalism constructs a civilisational alternative to the United States and its allies that at times resembles aspects of non-aligned discourse.

Yet Putin’s model diverges profoundly from Tito’s in practice, revealing the hollowness of civilisational rhetoric absent genuine institutional multiethnic accommodation.

Whereas Tito devolved significant fiscal, judicial, and administrative authority to republics, Putin has systematically recentralised power in the presidency and federal security organs, weakening regional governors and constraining their financial autonomy.

The 2014 annexation of Crimea and the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, justified in part through narratives of a “triune Russian nation” and alleged Western manipulation of Ukrainian identity, stand in direct contrast to Titoist principles of internal accommodation and external non-interference; they amount to expansionist imperial projects framed as civilisational reunification.

Most damningly, Putin’s multiethnic civilisation discourse serves as a legitimating language for sphere-of-influence imperialism in the “near abroad,” encompassing Ukraine, Belarus, the South Caucasus, and Central Asia, rather than as a mechanism for empowering minorities within the Russian Federation.

Tito’s break with Stalin aimed to secure Yugoslavia’s autonomy; Putin’s strategy seeks to reassert dominance over post-Soviet space. Conflicts in Georgia (2008), Crimea and Donbas (from 2014), and Ukraine since 2022 illustrate this inversion of non-alignment into hegemonic control.

Internally, Russia exhibits structural fragilities that recall elements of late Yugoslavia. The Chechen wars of the 1990s and early 2000s showed that Moscow’s multiethnic framework rested on coercion rather than robust institutions.

The subsequent arrangement with Ramzan Kadyrov, granting wide latitude in exchange for loyalty, created a personalised fiefdom rather than a stable federal compact—more akin to the wartime militias and local warlords that emerged from Yugoslavia’s collapse than to Tito’s disciplined party hierarchy.

The disproportionate mobilisation of ethnic minorities for the war in Ukraine, alongside evidence of mounting regional grievances, suggests that “multiethnic civilisation” risks devolving into a system of unequal burden-sharing likely to fuel resentment as economic and demographic pressures mount.

Comparative Analysis: Why Contemporary Leaders Cannot Replicate Tito’s Synthesis

No contemporary autocrat authentically replicates Tito’s multifaceted leadership model, highlighting why multiethnic federations remain structurally fragile under twenty-first-century conditions.

Tito possessed three material conditions largely absent in Xi, Abiy, or Putin: genuine revolutionary legitimacy transcending ethnic identity (rooted in anti-fascist struggle and victory), authentic non-aligned independence from hegemonic blocs (leveraging bipolar rivalry for economic advantage), and an institutional commitment—however imperfect—to decentralisation and workers’ self-management within a federal framework.

Contemporary leaders inherit different constraints. Xi presides over a party whose revolutionary origins are historically distant and whose legitimacy increasingly hinges on economic performance and Han-centric nationalism.

Abiy inherited an ethnic federal constitution he neither designed nor fully controls, and he operates in an international environment where Western and Chinese influence significantly circumscribe genuine non-alignment.

Putin leads a militarised petro-state facing demographic and economic stagnation, and he uses expansionist ventures and civilisational rhetoric to compensate for systemic weaknesses rather than to build inclusive institutions.

The global context has also shifted. Tito’s space for manoeuvre emerged from a relatively stable bipolar order in which non-aligned states could leverage competition between Washington and Moscow.

Today’s environment is more fluid and often more coercive, with multiple centres of power and tighter economic interdependence, making sustained neutrality harder to maintain.

At the same time, contemporary information technologies enhance the speed and scale of ethnic mobilisation, amplifying perceived grievances and making long-term elite bargains more fragile. Under these conditions, Titoist decentralisation can appear to outside observers as a prelude to secession rather than as a stabilising mechanism, particularly where trust in central institutions is low.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: The Institutional Cascade from Charisma to Fragmentation

The causal trajectory from Titoist central charisma to multiethnic fragmentation offers a template for diagnosing contemporary vulnerabilities.

Tito’s system rested on layered authority: supranational revolutionary legitimacy grounded in Partisan victory; party discipline that formally transcended ethnicity; decentralised federal and self-management institutions that diffused power; and a central leadership capable of arbitrating disputes and vetoing overt ethnonationalist bids.

After his death in 1980, the first layer collapsed, as no collective presidency could reproduce his personal authority.

The second layer eroded with the global delegitimisation of communism and Yugoslavia’s mounting economic crisis in the 1980s, which undercut ideological cohesion and spurred competition for scarce resources.

The third layer—decentralised republican and provincial institutions—then shifted from being a stabilising mechanism to a platform for exit, as Slovenia, Croatia, and later other republics viewed secession as more attractive than continued participation in a failing federation.

This sequence—charisma and ideology decline; economic stress rises; decentralised institutions become vehicles for ethnonationalist projects—is instructive for assessing China, Ethiopia, and Russia.

Xi’s centralisation reverses the decentralising dimension of Titoism but at the cost of alienating regional and minority elites who previously enjoyed more room to manoeuvre, thereby raising the stakes if central legitimacy falters.

Abiy’s partial recentralisation amid liberalisation dissolved the previous authoritarian equilibrium without erecting durable supranational institutions, encouraging actors such as the Tigray People’s Liberation Front to opt for armed resistance rather than negotiated compromise.

Putin’s system similarly relies on personalised authority and security structures, with limited constitutional or federal safeguards for minorities; as economic and military pressures intensify, regions may reassess the benefits of remaining in a centralised, Moscow-dominated order.

Across these cases, leaders facing challenges to legitimacy have repeatedly relied on coercion—mass surveillance, counterinsurgency campaigns, and large-scale wars—to manage multiethnic tensions.

Such strategies can suppress conflict temporarily, but they exacerbate grievances and create constituencies with strong incentives to seek autonomy or independence once central coercive capacity wanes or external conditions shift. Tito’s system postponed this reckoning by combining decentralisation with non-aligned economic and diplomatic backing; contemporary regimes often postpone it only through force.

Future Steps: Pathways Toward Multiethnic Stability Without Titoist Charisma

For policymakers confronting multiethnic fragmentation today, the central challenge is to replicate Tito’s stability-generating functions without relying on singular charismatic figures or Cold War–style non-alignment.

First, supranational institutions must play a greater role in mediating ethnic conflict and guaranteeing minority rights. The European Union’s legal and institutional architecture—including the European Court of Human Rights and extensive minority-protection norms—offers one model of post-national governance that helps mitigate ethnonationalist pressures within member states.

Adapting analogous mechanisms to other regions, whether through the African Union, ASEAN, or bespoke regional human-rights and arbitration bodies, could diffuse authority across institutions and away from personalist leaders.

Second, fiscal federalism must be transparent and rules-based to prevent wealthier regions from viewing the federation as a permanent redistributive burden, a dynamic evident in late Yugoslavia and visible in other multiethnic settings. Constitutionally anchored revenue-sharing formulas and independent fiscal councils, drawing on best practices from federations such as Germany, can reduce perceptions of unfairness and diminish secessionist incentives.

Third, consociational and power-sharing arrangements that provide minorities with meaningful veto points and guaranteed representation can help prevent a “tyranny of the majority.” The post-Dayton institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, despite serious flaws, illustrate how ethnic quotas and shared governance structures can at least forestall renewed large-scale warfare.

Elements of such arrangements could be adapted to settings like Ethiopia, where structured representation for Oromos, Amharas, Tigrayans, and others might mitigate zero-sum competition at the centre, or, in a more hypothetical scenario, to any future attempts at meaningful autonomy for regions within large states such as China.

Fourth, genuine strategic neutrality remains a valuable asset for fragile multiethnic states, even in a complex multipolar system. Countries such as India, Brazil, and Indonesia demonstrate that flexible, non-aligned foreign policies can attract investment and diplomatic space without rigid bloc allegiance. Encouraging multiethnic polities facing internal tensions to avoid deep security alignment with any single great power may reduce external incentives to instrumentalise minority grievances.

Fifth, early and sustained international mediation and arbitration are crucial. Agreements such as the Ohrid Framework in North Macedonia show how timely intervention, power-sharing, and minority-rights guarantees can defuse escalating violence; comparable efforts came too late or in too limited a form in Yugoslavia’s dissolution.

Creating regional dispute-resolution mechanisms with authority to monitor, mediate, and, where necessary, impose remedies for minority-rights violations would provide an institutional backstop against the escalation dynamics visible in Tigray, Donbas, Rakhine State, and other flashpoints.

Conclusion

Tito’s Irreplaceable Legacy and Contemporary Fragility

Josip Broz Tito’s governance model—synthesising revolutionary legitimacy transcending ethnicity, non-aligned strategic independence, and decentralised federal institutions granting regional autonomy whilst preserving federal cohesion—remains structurally unreplicable under contemporary conditions, yet it illuminates the conditions for multiethnic state stability that current leaders frequently violate.

Xi Jinping’s centralising authoritarianism, Han-centric nation-building, and emergent bloc politics depart sharply from Tito’s decentralisation and non-alignment, exposing China to heightened risks should party legitimacy waver.

Abiy Ahmed’s Medemer vision, absent robust institutions and revolutionary credentials, proved unable to prevent the devastation of the Tigray war, demonstrating that conciliatory rhetoric and partial reforms cannot substitute for durable accommodation mechanisms.

Vladimir Putin’s “multiethnic civilisation” serves less as an inclusive domestic compact than as an ideological frame for imperial restoration in the post-Soviet space, inverting Tito’s pursuit of autonomy into a project of domination.

Without leaders—or, more importantly, institutions—capable of combining elements of Tito’s innovations (devolution, supranational legitimacy, strategic non-alignment) with democratic accountability, transparent minority protections, and credible international oversight, multiethnic federations are likely to remain vulnerable to recursive fragmentation under conditions of economic stress and geopolitical competition.

In an era marked by growing great-power rivalry, ideological polarisation, and technologically accelerated identity mobilisation, the absence of credible functional equivalents to Tito’s stabilising architecture ensures that polities such as Ukraine, Ethiopia, Myanmar, and potentially segments of larger states will continue to face Yugoslav-style dissolution risks unless substantial institutional innovation occurs.