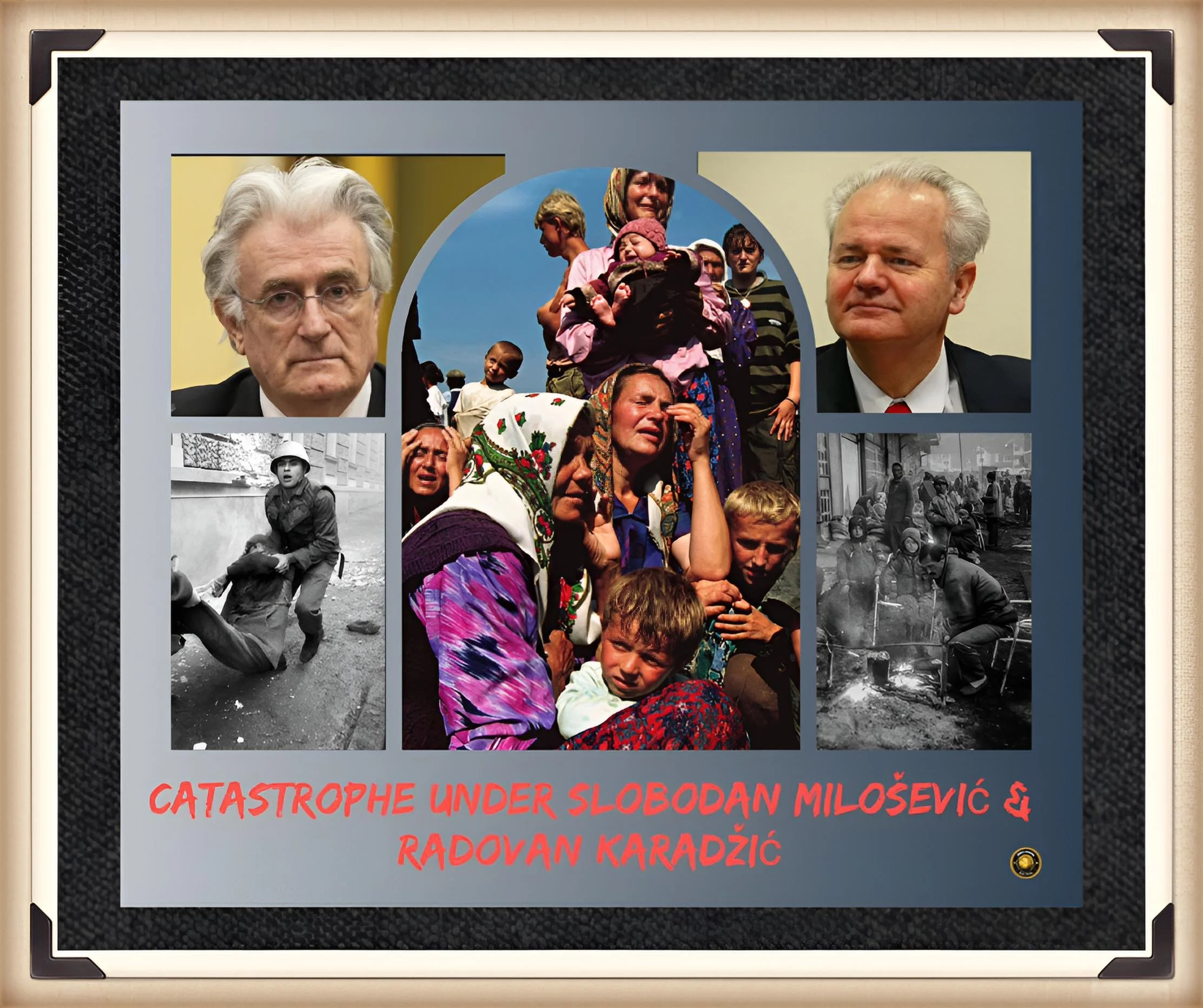

Ethnic Cleansing and Genocide: The Rise of Serbian Nationalism and the Yugosla Catastrophe under Slobodan Milošević & Radovan Karadžić -V

Executive Summary

Following Marshal Tito’s death in 1980, Yugoslavia’s carefully balanced federal system fractured as nationalist movements surged across the republics.

Slobodan Milošević emerged as Serbia’s paramount leader in 1989, instrumentalizing Serbian nationalist ideology to consolidate power while orchestrating territorial expansion through military campaigns.

His strategic support for Radovan Karadžić’s Bosnian Serb forces between 1992 and 1995 catalysed systematic genocide, resulting in approximately 100,000 deaths, with the Srebrenica massacre of July 1995 claiming over 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) indicted Milošević on 66 counts including genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes across Kosovo, Croatia, and Bosnia, establishing the first conviction of a sitting head of state in international criminal law. Karadžić, as President of Republika Srpska and Supreme Commander of Bosnian Serb forces, directed the implementation of systematic ethnic cleansing campaigns and was subsequently convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity, receiving a life sentence.

Both leaders’ prosecutions exposed the mechanics of modern atrocity: the weaponisation of nationalist mythology, institutional capture, and the deliberate construction of a joint criminal enterprise linking political leadership to field-level perpetrators across administrative, military, and paramilitary hierarchies.

Introduction

The disintegration of Yugoslavia from 1990 to 1999 represents one of the most catastrophic geopolitical collapses of the late twentieth century, triggering successive wars across Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo.

Within this cascade of violence, the Bosnian War of 1992–1995 emerged as the epicentre of atrocity, culminating in the first systematic genocide perpetrated in Europe since the Holocaust.

The tragic arc from Tito’s unifying (yet repressive) state structure to the genocidal breakup reveals how the removal of centralised authority created space for subnational leaders to mobilise ethnic fear and mobilise state apparatus toward mass killing.

The cases of Slobodan Milošević and Radovan Karadžić exemplify how ostensibly political actors—a lawyer-turned-revolutionary nationalist (Milošević) and a poet-psychiatrist (Karadžić)—deployed propaganda, institutional networks, and military force to execute systematic campaigns of extermination disguised as ethnic separation.

Historical Context: The End of the Tito Era and the Resurgence of Nationalism

Tito’s Federal Structure and the Suppression of Ethnic Tension

From 1945 until his death on 4 May 1980, Josip Broz Tito maintained unprecedented unity across Yugoslavia’s six republics and two autonomous provinces through a combination of forceful ideological commitment to communism, cult-of-personality authoritarianism, and careful institutional engineering.

The 1974 Constitution established a rotating presidency among the republics, decentralised economic management, and explicitly suppressed nationalist sentiment as antithetical to Yugoslav ideology.

This system functioned effectively so long as Tito’s unchallenged authority enforced compliance.

However, the Constitution itself encoded Yugoslavia’s latent fragmentation: each republic retained substantial sovereignty, media control, and security apparatus; ethnic Serbs dispersed across Croatia and Bosnia remained politically organised and historically aggrieved; and economic divergence between northern republics (Slovenia, Croatia) and poorer southern regions (Kosovo, Macedonia) fostered competing visions of federation or confederation.

The Void After 1980

Tito’s death removed what international observers identified as Yugoslavia’s primary unifying force.

The subsequent decade witnessed the crumbling of communism across Eastern Europe, the ideological erosion of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia, and the rise of competitive nationalist parties in multi-party elections of 1990.

Critically, the system Tito constructed—collective presidency, consensus-based decision-making, and weak federal centre—proved incapable of managing ethnic tensions without a dominant personality enforcer.

The 1980s witnessed escalating demands by Kosovo Albanians for republican status, violent ethnic clashes in Kosovo, and the emergence of Serbian nationalist intellectual movements (particularly the 1986 SANU Memorandum) articulating claims of Serbian historical victimisation and the need for territorial consolidation.

The Rise of Slobodan Milošević: From Communist Apparatchik to Nationalist Leader (1987–1991)

The 1987 Strategic Pivot

Slobodan Milošević’s trajectory encapsulates the ideological inversion that propelled the Yugoslav Wars. Born in 1941, educated as a lawyer, and a mid-ranking communist apparatchik through the 1970s and early 1980s, Milošević held the persona of a hard-line orthodox communist who publicly condemned nationalism as treachery.

In 1987, dispatched to Kosovo to restore order among protesting Serbs, Milošević seized an unprecedented political opportunity.

Rather than impose communist discipline, he channelled and amplified ethnic grievances, adopting the nationalist programme that had been intellectual currents within Serbian academia.

At a pivotal Kosovo rally, Milošević deployed the rhetorical formula that would define his rule: “No one may beat you,” casting himself as the protector of the Serbian nation.

This “Kosovo switch” proved transformative. Riding nationalist sentiment, Milošević consolidated power in the Serbian Communist Party by defeating reform-minded rivals, most prominently Ivan Stambolić, in September 1987.

He then orchestrated the removal of Kosovo’s autonomy under the 1974 Constitution, reorganised Vojvodina’s autonomous status, and repositioned Serbia within Yugoslavia as the demographic and political centre of a reconfigured state.

The Media Machine and the “Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution”

Between 1987 and 1990, Milošević’s regime weaponised state media (particularly television) to disseminate nationalist messaging across Serbia.

Orchestrated rallies—styled as the “anti-bureaucratic revolution” or “rallies of truth”—mobilised hundreds of thousands of Serbs and broadcast imagery of ethnic Serb victimisation in Kosovo and historical Serbian grievance dating to the 1389 Battle of Kosovo.

The cumulative effect constructed a paranoid nationalist consciousness: Serbs were portrayed as facing existential threats from internal Albanian and Croat enemies and external Western conspirators.

This propaganda infrastructure, combined with Milošević’s control of state security forces and the Serbian branch of the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), created the preconditions for military mobilisation.

Electoral Consolidation and Constitutional Revision

In the first multi-party elections of 1990, Milošević’s Socialist Party of Serbia defeated reform-oriented opponents and consolidated single-party dominance.

Simultaneously, Milošević’s regime enacted constitutional changes stripping Kosovo and Vojvodina of autonomy, placing their resources and security forces directly under Serbian control.

Crucially, this gave Milošević de facto command over the JNA units stationed within Serbian territory—a capability that would prove decisive in the wars to follow.

The Bosnian War and the Genocide: 1992–1995

The Bosnia Independence Referendum and Milošević’s Strategic Objective

Following Slovenia’s and Croatia’s declarations of independence in June 1991, Bosnia and Herzegovina held an independence referendum on 1–2 March 1992.

The electorate voted overwhelmingly for independence, but the referendum was boycotted by the Serbian Democratic Party (SDS), led by Radovan Karadžić.

The result immediately polarised Bosnia: the internationally recognised government, led by Bosniak (Muslim) pluralist Alija Izetbegović, assumed power; meanwhile, Bosnian Serbs, concentrated in eastern Bosnia and intermixed with Bosniak and Croat populations, refused to accept subordination to a non-Serb-led state.

Milošević’s objective was explicit: to prevent the emergence of an independent, multi-ethnic Bosnian state and instead carve out Serb-controlled territory that would either merge with Serbia or function as a Serbian statelet.

This goal aligned with the broader geopolitical project articulated during the anti-bureaucratic revolution—the creation of a “greater Serbia” encompassing all territories where Serbs lived or had historical claims.

Radovan Karadžić and the Six Strategic Objectives

In May 1992, as Bosnian Serb forces seized territory through military campaigns, Radovan Karadžić, then President of Republika Srpska, publicly announced the “six strategic objectives” for the Serbian people in Bosnia:

Establish state borders separating Serbs from other ethnic communities.

Set up a corridor between Semberija and Krajina.

Establish a corridor in the Drina River valley, eliminating the river as a boundary between Serbian states.

Establish borders on the Una and Neretva rivers.

Divide Sarajevo into Serb and Bosniak zones.

Ensure access to the sea for Republika Srpska.

These objectives, though framed in territorial and geopolitical language, translated operationally into systematic ethnic cleansing. Karadžić, a psychiatrist and poet by training, possessed no prior military experience yet assumed the position of Supreme Commander of the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS), a 100,000-strong force formally commanded by General Ratko Mladić.

This arrangement reflected the dual-track command structure: Karadžić represented the political leadership of the self-proclaimed Bosnian Serb state, while Mladić operated the military apparatus.

However, Milošević maintained critical leverage: he controlled the supply of arms, ammunition, and military advisors flowing from Serbia to the VRS, and he personally directed certain sensitive operations through the use of special forces units (officially “volunteers”) dispatched from Serbian territory.

The Joint Criminal Enterprise and the Mechanisms of Genocide

Evidence presented to the ICTY established that Milošević, Karadžić, and other senior figures participated in a joint criminal enterprise (JCE) with the purpose of forcibly removing the majority of non-Serbs—particularly Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats—from large portions of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The JCE encompassed multiple layers:

Political Direction

Karadžić, as President of Republika Srpska and later Supreme Commander, issued orders through the Presidency and Supreme Command.

Momčilo Krajišnik, President of the Bosnian Serb Assembly, and Biljana Plavšić, Vice President of Republika Srpska, formed the triumvirate of Bosnian Serb political authority.

All three coordinated with Milošević, who exercised “command authority” and “de facto control” over the VRS through control of logistics, weapons, and strategic direction.

Administrative Apparatus

In municipalities across eastern and central Bosnia, Bosnian Serb authorities established “Crisis Staffs” and “War Presidencies” that merged civilian and military authority.

These bodies, subordinate to the Sarajevo-based Presidency and informed by directives from the SDS Main Board, implemented the practical dismantling of multi-ethnic society.

They issued orders for the detention of Bosniak and Croat civilians, organised forced labour, confiscated property, and coordinated with military units in the seizure of territory.

Military Operations

The VRS conducted coordinated offensives to seize municipalities, primarily between late March and December 1992, though operations continued through 1995.

After military takeovers, Bosnian Serb forces, acting in concert with local authorities and paramilitary units (including the notorious Arkan’s Tigers and Seselj’s White Eagles, which were nominally “volunteers” but received Serbian government support and direction), implemented systematic terror against civilian populations.

Detention and Extermination

Tens of thousands of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats were rounded up and imprisoned in camps and detention facilities.

The ICTY indictments identified at least 32 major camps and detention centres established by Bosnian Serb authorities, including the notorious Omarska, Keraterm, and Trnopolje camps in Prijedor municipality, Luka in Brčko, and KP Dom in Foča.

Within these facilities, Detainees faced systematic torture, sexual violence (particularly rape as a weapon of genocide), forced labor, and starvation.

Thousands died in detention or were extracted and summarily executed at remote locations.

The Srebrenica Massacre: July 1995

The pinnacle of the genocide occurred in Srebrenica, which had been designated a United Nations “safe area” in April 1993.

By July 1995, the UN-protected enclave had swollen to approximately 40,000 Bosniak refugees, predominantly women, children, and the elderly, due to ethnic cleansing campaigns in surrounding municipalities.

On 6–11 July 1995, Bosnian Serb forces, under the direct command of General Ratko Mladić and acting on orders approved by Karadžić, attacked the enclave with artillery and infantry.

As VRS forces penetrated the perimeter, approximately 15,000 Bosniak men and boys fled into nearby woods, while 8,000–10,000 others sought shelter at the Dutch peacekeeping battalion compound at Potočari.

Over the subsequent week (12–18 July 1995), Bosnian Serb forces executed more than 8,000 Bosniak males in a systematically organised manner.

Executions occurred at multiple locations: the Kravica warehouse, the Grbavci school, the Branjevo Military Farm, and along the banks of the Drina River.

Survivors and forensic evidence revealed that victims included elderly men, teenagers, and even younger children. Bodies were bulldozed into mass graves, many subsequently disinterred and reburied in secondary graves to obscure evidence.

By conservative international estimates, the Srebrenica massacre constitutes genocide—the intentional destruction, in whole or in substantial part, of the Bosniak group in that geographic area.

Broader Ethnic Cleansing Across Bosnia: Casualty Figures and Territorial Consolidation

Beyond Srebrenica, Bosnian Serb forces conducted ethnic cleansing operations across approximately 17 municipalities with demonstrated intent to remove non-Serb populations. In municipalities such as Prijedor, Bijeljina, Banja Luka, Foca, Višegrad, and Zvornik, thousands of Bosnian Muslims and Croats were killed during or immediately after military takeovers, subjected to detention and torture, or forcibly deported.

By November 1995, when the Dayton Agreement ended major combat, the Bosnian Serb entity (Republika Srpska) controlled approximately 51% of Bosnian territory—vastly exceeding the proportion of Bosnian Serb population (approximately 31% pre-war)—and had achieved the near-complete ethnic separation of Serbs from non-Serbs in regions under their control.

The aggregate human toll was staggering: approximately 100,000 people killed during the 1992–1995 conflict, with Bosniaks constituting roughly 80% of fatalities. An estimated 2.2 million people were displaced or became refugees, with hundreds of thousands languishing in camps.

Beyond physical destruction, the psychological trauma of witnessing mass killings, systematic torture, sexual enslavement, and the destruction of cultural heritage (mosques, churches, libraries, archives) inflicted generational damage across Bosnian society.

The Siege of Sarajevo: Terrorism Against Civilians

Concurrent with ethnic cleansing in eastern Bosnia, Bosnian Serb forces maintained a continuous blockade and bombardment of Sarajevo from May 1992 until February 1996.

The siege lasted 1,425 days—the longest siege of a capital city in modern European warfare. Bosnian Serb artillery, positioned in the hills surrounding the city, subjected the civilian population to approximately 329 mortar shells per day, with over 500,000 bombs dropped across the city during the siege.

The Sarajevo Romanija Corps, a VRS unit formally established from JNA forces in May 1992, implemented a deliberate strategy of terrorising civilians. Snipers targeted civilians collecting water, waiting in bread queues, tending vegetable gardens, or playing football.

The “Markale massacres”—mortar attacks on the central marketplace in February 1994 (68 killed) and August 1995 (43 killed)—exemplified the indiscriminate targeting of civilians.

Total casualties from the siege numbered approximately 13,952, including 5,434 civilians. The conditions—absence of gas, electricity, running water, and consistent threat of death—created a climate of perpetual terror designed to force the evacuation of Muslims from the city and consolidate Serb control.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: How Nationalist Ideology Became Genocide

Ideological Foundation and Institutional Capture

The transition from nationalist rhetoric to systematic genocide followed a causal chain rooted in institutional dynamics.

Milošević’s manipulation of Serbian nationalism served initially as a tool for consolidating his personal power against communist-era elites. However, once nationalist ideology became state policy (circa 1988–1990), it created irreversible political incentives.

Competing Serbian leaders could not appear less committed to Serbian national interests; thereby, nationalism spiralled into ever-more-extreme articulations.

The state media apparatus, controlled by Milošević, became a unidirectional propaganda channel depicting Serbs as besieged by enemies—Albanians in Kosovo, Croats, and Muslims in Bosnia.

Critically, nationalist ideology provided the intellectual framework for territorial claims.

The narrative of “natural” Serbian territory encompassing all lands where Serbs lived, combined with historical myths (the 600-year anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, which had become a symbol of Serbian martyrdom), justified military conquest and ethnic removal as national “recovery” rather than aggression.

Military Preparedness and the Yugoslav People’s Army

The Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), inherited from communist Yugoslavia, remained the most powerful military force in the region with a predominantly Serbian officer corps. Milošević systematically politicised the JNA, removing non-Serbian officers and appointing loyalists.

By 1991, when the wars began, the JNA became the de facto instrument of Serbian expansionism.

Although the JNA formally “withdrew” from Bosnia in May 1992, the withdrawal was illusory: officers remained as advisors, weapons and logistics continued flowing from Serbian territory, and elite JNA units (re-branded as “volunteers”) participated directly in Bosnian operations.

This military infrastructure provided the capability for Karadžić and the VRS to implement the ethnic cleansing design. The VRS, though nominally independent, functioned as a proxy force dependent upon Serbian supply chains and guidance from Milošević’s regime.

The Camp System: Bureaucratic Genocide

The establishment of detention camps represented the most direct mechanism linking political decisions to mass killing.

Karadžić’s indictment specified 32 camps where tens of thousands of Bosnian Muslims and Croats were imprisoned under conditions calculated to cause death through starvation, disease, and torture.

The camps were not aberrations but systematically organised components of the ethnic cleansing strategy.

The camp system exemplified the banality of genocide: bureaucratic procedures for registering detainees, supply chain management for food rationing (often withheld), medical facilities (often non-existent or used to torture), and guard rotations.

Camp commanders reported to municipal War Presidencies, which reported to the Bosnian Serb Presidency. Victims from camps who were “transferred” for “exchange” or “resettlement” were often instead extracted and executed at designated killing sites.

This assembly-line quality—where political leaders issued directives, administrators implemented procedures, and soldiers executed orders—mirrored industrial-era atrocities, yet was justified through nationalist narrative as necessary measures against an internal enemy.

Sexual Violence as a Weapon of Genocide

The ICTY indictments emphasised that Bosnian Serb forces systematically employed rape and sexual enslavement as instruments of genocide.

Women and girls were raped during military operations, detained in camps specifically for sexual abuse, and forcibly impregnated with the explicit intent to change the ethnic composition of communities.

Survivors testified that perpetrators explicitly stated that their objective was to create “Serb babies.”

This gendered dimension of genocide operated on multiple levels: as a tool of terrorising and humiliating the Bosniak population, as a mechanism of ethnic replacement (forcing through demographic change what could not be achieved through pure expulsion), and as an extension of the totalising dehumanisation that enabled mass killing.

Evidence and Findings: The ICTY Prosecutions

Milošević’s Indictment and Trial

Slobodan Milošević was indicted by the ICTY on 24 May 1999 during the Kosovo War (later supplemented with indictments for crimes in Croatia and Bosnia).

The indictment charged him with 66 counts including genocide, complicity in genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

Specifically regarding Bosnia, Milošević faced charges of genocide in eight municipalities (Bijeljina, Bratunac, Brčko, Doboj, Foča, Prijedor, Srebrenica, Vlasenica, and Zvornik), crimes against humanity including extermination, murder, deportation, and imprisonment, and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions.

The prosecution’s theory rested on Milošević’s “command responsibility” and his membership in a joint criminal enterprise. Evidence presented at trial demonstrated that:

Control of Supply: Milošević maintained command authority over supply lines of weapons, ammunition, fuel, and military advisors flowing from Serbia to Bosnian Serb forces.

Deployment of Special Forces: Serbian security services, personally loyal to Milošević, deployed elite units to conduct initial takeovers and high-profile killings, then withdrew, leaving local forces to implement systematic campaigns.

Direct Communications: Intercepted communications and testimony from military officers indicated that Milošević directly approved major military operations and received reports on their execution.

Financial Support: Serbia paid the salaries of VRS soldiers and sustained the economy of Bosnian Serb territories, creating dependency relationships that ensured compliance with strategic directives.

However, Milošević died on 11 March 2006 before the trial concluded. The Trial Chamber terminated proceedings without issuing a final judgment.

In a separate judgment in Karadžić’s case (2016), the ICTY Trial Chamber found insufficient evidence from that particular proceeding that Milošević “participated in the realisation of the common criminal objective” of the JCE, though this finding was specific to that trial’s evidence and did not constitute an acquittal.

The question of Milošević’s ultimate culpability remains jurisprudentially incomplete, though the overwhelming factual evidence presented indicated his integral role in orchestrating the Bosnian campaign.

Karadžić’s Conviction

Radovan Karadžić was apprehended in 2008 after 13 years in hiding and tried before the ICTY from 2012 onwards.

On 24 March 2016, the Trial Chamber found Karadžić guilty on ten of eleven counts. Crucially, he was convicted of genocide specifically in relation to the Srebrenica massacre, with the court finding that he possessed the requisite intent to destroy, in whole or in substantial part, the Bosniak population of Srebrenica.

The conviction encompasse

One count of genocide (Srebrenica massacre)

Five counts of crimes against humanity (persecution, extermination, murder, torture, forced displacement)

Four counts of war crimes (attacks on civilians, unlawful shelling, unlawful attacks on undefended objects, taking of hostages)

Critically, the Trial Chamber found that the “whole population of Sarajevo was terrorised and lived in extreme fear” as a result of Karadžić’s role in orchestrating the siege, and that “his support” for the siege was so instrumental that “without his support it would not have occurred.”

Karadžić was acquitted of one count of genocide related to crimes in seven other municipalities (acquittal suggesting the court found insufficient evidence of genocidal intent in those contexts, though crimes against humanity convictions stood).

He was sentenced to life imprisonment, upheld on appeal in 2019.

Institutional and Legal Mechanisms: How Atrocity Succeeded

The Failure of the International Community

The Bosnian genocide unfolded not in a geopolitical vacuum but amid the presence of international institutions and Western powers. The United Nations established a Safe Areas mandate for Srebrenica, Žepa, Goražde, Bihać, and Tuzla in April 1993, yet provided insufficient forces (approximately 60,000 lightly-armed UN peacekeepers for a territory the size of England) to enforce protection.

The “safe areas” became cages where civilian populations were trapped, besieged, and starved. The Dutch battalion stationed at Srebrenica, numbering approximately 400 soldiers, faced overwhelming odds and were unable to prevent the July 1995 massacre despite witnessing Bosnian Serb troops entering the enclave.

This failure, resulting from underresourced mandates and constrained rules of engagement, exposed the gap between international legal commitments and enforcement capacity.

The Role of Paramilitary Networks

Bosnian Serb ethnic cleansing relied substantially on paramilitary units—formally non-state actors but in practice operating under state direction and supply.

Željko Ražnatović, known as “Arkan,” commanded a notorious unit called the “Tigers” that pioneered ethnic cleansing tactics in eastern Slavonia (Croatia) before relocating to Bosnia, where his unit participated in atrocities in Bijeljina and other municipalities.

Vojislav Šešelj’s “White Eagles” similarly operated nominally as nationalist volunteers whilst receiving Serbian government support. These paramilitaries served as shock troops whose atrocities were deniable (being technically non-state actors) yet were systematised and directed by political leadership.

Conclusion

Lessons for International Criminal Law and Genocide Prevention

The prosecution and conviction of Karadžić, together with the indictment of Milošević, represented landmark achievements in international criminal law. For the first time, a sitting head of state (Milošević) was charged with genocide, establishing the principle that executive immunity does not shield leaders from accountability for systematic atrocities.

The ICTY’s jurisprudence on joint criminal enterprise, command responsibility, and crimes against humanity provided the evidentiary and legal framework for demonstrating that institutional hierarchies—from political directives through military chains of command to field-level perpetrators—could be prosecuted as coherent criminal enterprises.

However, the prosecutions also revealed limitations. Milošević’s death before final judgment left the definitional question of his ultimate liability unresolved. The ICTY’s completion and closure in 2017 meant that thousands of mid-level perpetrators (guards, soldiers, municipal officials) were never prosecuted.

The psychological and demographic consequences of the genocide persist in Bosnia: generational trauma, continuing ethnic polarisation, and the persistence of genocide denial within Serbian political discourse undermines reconciliation.

The Bosnian genocide demonstrates that modern atrocity does not require the totalitarian apparatus of Nazi Germany or Stalinist USSR.

Rather, the capture of a single state (Serbia) by a nationalist leader willing to weaponise mythology, propaganda, and the existing security apparatus; the existence of dispersed target populations lacking political representation; and the absence of credible international enforcement mechanisms created conditions sufficient for systematic mass killing.

The transition from rhetoric to genocide occurred within 12–24 months (1990–1992), a compressed temporal arc that ought to inform contemporary genocide prevention policy.