The Cascade of Collapse: Why Ten Yugoslav Wars Unfolded from a Single Federation and What It Reveals About Fragile Multi-Ethnic States Today - Part II

Executive Summary

Yugoslavia’s Martial Odyssey: A Decade-Long Descent into Ethnic Conflagration and Regional Disintegration

Yugoslavia, encompassing both the Kingdom (1918–1941) and the Socialist Federal Republic (1945–1992), engaged in at least ten distinct conflicts across its history, each reflective of deeper structural fissures that rendered the multi-ethnic federation inherently unstable.

The period spanning 1991 to 2001 witnessed an especially cataclysmic unravelling, culminating in 130,000 to 140,000 deaths, the displacement of over two million civilians, and systematic genocides that fundamentally reshaped European security architecture.

This analysis elucidates the intricate causality between supranational state collapse, economic coercion by international financial institutions, and the mobilisation of primordial nationalisms by opportunistic elites, whilst positioning Yugoslav disintegration as a cautionary template for understanding contemporary geopolitical fractures from Ukraine to the Middle East.

The wars demonstrate that polyethnic federations lacking resilient institutional mechanisms, enforceable wealth-sharing arrangements, and supra-national legitimacy succumb inexorably to ethno-nationalist spirals once charismatic central authority wanes and fiscal asymmetries accumulate.

Introduction

Yugoslavia’s Unravelling: The Decade That Spawned Genocide, NATO Intervention, and Multipolar Backlash—Lessons for Today’s Fractured World

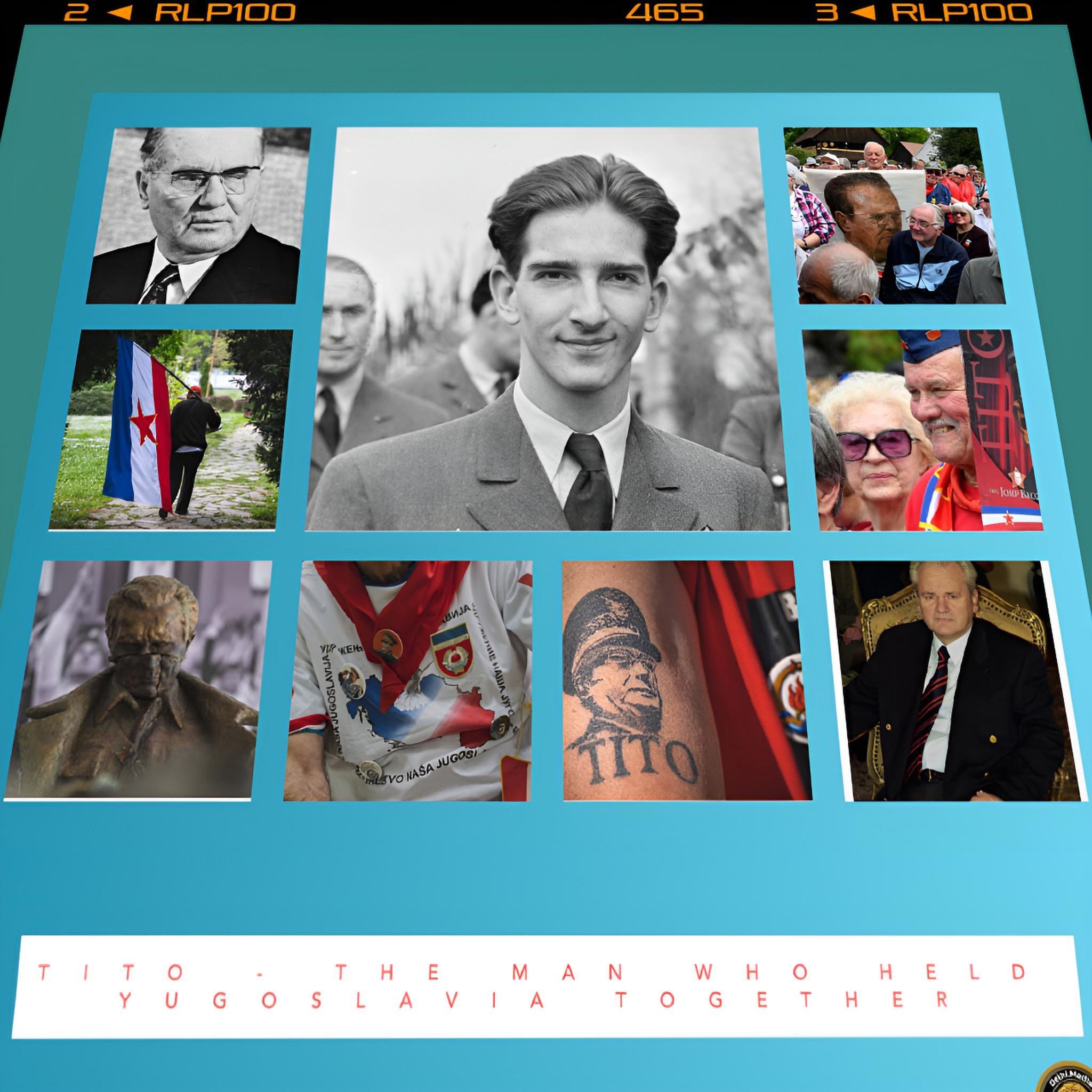

The federation that Josip Broz Tito constructed from the ruins of Austro-Hungarian hegemony represented an experiment in containing disparate South Slavic identities within a republican framework ostensibly transcending ethnic particularity through “Brotherhood and Unity” and non-aligned socialist internationalism.

Yet Tito’s 1980 death removed the singular supra-national figure whose charisma had suppressed latent resentments amongst Serbs, Croats, Slovenes, Bosniaks, Macedonians, and Montenegrins.

Simultaneously, the 1974 Constitution’s devolution of federal power to constituent republics and autonomous provinces—intended to mitigate centrifugal pressures—paradoxically concentrated decision-making within increasingly ethno-nationalist republican leaderships. When combined with the 1980s debt crisis precipitated by IMF “shock therapy,” this institutional framework collapsed entirely.

The ensuing wars were neither spontaneous eruptions of primordial hatreds nor externally imposed interventions, but rather the causal confluence of economic strangulation, constitutional asymmetries, and the calculated mobilisation of ethnic grievance by elites seeking to consolidate power.

These conflicts resulted in approximately 140,000 deaths, systematic genocides indicted by international tribunals, and the fragmentation of a once-integrated regional economy into economically isolated post-war states still grappling with reconstruction and reconciliation decades hence.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia: Inter-War Conflicts and the Axis Invasion

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, formally established in December 1918 from the wreckage of Austro-Hungary, inherited not merely territorial disputes but fundamentally incompatible national aspirations.

The Revolutions and Interventions in Hungary (1918–1920) constituted Yugoslavia’s first military engagement as a unified state. As the Hungarian Soviet Republic under Béla Kun sought to reclaim territories lost to the Entente, the nascent Yugoslav state joined Romanian and Czechoslovak forces to dismantle this Bolshevik incursion.

Yugoslav forces advanced into the Banat and Bačka regions, securing territories ethnically diverse yet strategically vital for controlling the Danube approaches.

The Treaty of Trianon (1920) formalised these territorial gains, yet simultaneously engendered irredentist sentiment amongst dispossessed Magyar populations that would resurface violently two decades hence.

The conflict’s significance transcended its immediate military dimensions: it established Yugoslavia as a regional power willing to employ force to consolidate territorial claims, whilst simultaneously embedding within the kingdom a tradition of external validation through great-power alignment—a pattern that would recur throughout Yugoslav history.

The Austro-Slovene Conflict in Carinthia (1918–1919) emerged from linguistic and ethnic ambiguities embedded within mixed-ethnicity Alpine borderlands. Slovene militia forces under Rudolf Maister engaged Austrian paramilitary units for control of strategically important towns including Marburg and Jezersko.

The conflict was settled not through military victory but through Allied arbitration, wherein American mediators recommended a plebiscite in the disputed Klagenfurt Basin. Though the plebiscite resulted in Austrian retention of southeastern Carinthia, the Yugoslav acquisition of Maribor and the Meža Valley signified symbolic victory for Slovene nationalist aspirations.

This early conflict established patterns evident throughout Yugoslav history: territorial disputes were never merely administrative delineations but proxies for competing national narratives, rendered intractable through the language of ethnic self-determination mobilised selectively by various elites.

The Christmas Uprising (January 1919) in Montenegro reveals the Kingdom’s internal fractures with particular clarity. Conservative Montenegrin elites divided between Greens, who sought to preserve Montenegrin statehood and confederal status within the South Slavic union, and Whites, who advocated immediate absorption into a centralised Serbian-dominated kingdom.

The Greens, led by Krsto Popović militarily and Jovan Plamenac politically, mounted armed resistance to the Podgorica Assembly’s unionist decision. Serbian regulars, deployed northward to suppress this insurrection, defeated the Greens militarily by Orthodox Christmas (7 January). However, guerrilla resistance persisted in Montenegrin mountains under Savo Raspopović until 1929, indicating that even in victory, the centralised state failed to eliminate Montenegrin separatist sentiment.

This foundational conflict presaged the 1990s disputes: forced unification under Serb-dominated institutions generated defensive mobilisation amongst peripheral nationalist elites, who perceived threats to their ethnic group’s established autonomy and legitimacy.

The Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941 shattered the Kingdom’s fragile equilibrium within eleven days, exposing the military inadequacy of the Royal Yugoslav Army and the regime’s inability to manage multi-ethnic mobilisation during existential crisis.

German air forces bombed Belgrade indiscriminately, whilst German 2nd Army pincers drove southeastward from Austrian territory and Bulgarian border crossings. Italian forces advanced along the Dalmatian coast, and Hungarian 3rd Army moved through Banat.

By 17 April, Yugoslav high command capitulated, with over 254,000 soldiers taken prisoner. Civilian casualties exceeded 300,000 during initial operations, including systematic atrocities perpetrated by the Ustaše regime (the fascist puppet state controlling Croatia) and Wehrmacht units.

Approximately 67,000 Jews and 27,000 Roma were murdered by Axis occupation forces and their local collaborators during 1941–1945, establishing genocidal precedents that would echo across the 1990s conflicts.

The invasion’s devastation was followed by Partisan resistance under Tito, which by 1945 had assumed control of Yugoslavia and established the socialist federation on explicitly anti-fascist and multi-national grounds.

Socialist Federal Republic: Cold War Interventionism and Internal Repression

Tito’s post-war reconstruction of Yugoslavia as a federal socialist state composed of six nominally equal republics and two autonomous provinces represented a deliberate attempt to transcend ethnic nationalism through revolutionary internationalism and workers’ self-management.

The 1948 Tito-Stalin rupture transformed Yugoslavia into the world’s first non-aligned nation, permitting Tito to position the federation as a strategic asset to Western powers despite its socialist orientation.

This geopolitical utility, combined with Tito’s demonstrated willingness to employ the Yugoslav People’s Army against domestic challengers, provided Yugoslavia with economic lifelines from both East and West that subsided far larger debt burdens than Albania or other Soviet satellites could accumulate.

Operation Valuable (1949–1956) exemplified this Cold War positioning. Following the Cominform expulsion, Yugoslavia cooperated covertly with American and British intelligence to destabilise Enver Hoxha’s Stalinist Albania. Yugoslav forces operated alongside CIA agents in infiltration operations designed to foment internal Albanian resistance, whilst covert teams landed by sea to establish guerrilla bases in Albanian mountains.

The CIA concluded in 1949 that “a purely internal Albanian uprising at this time is not indicated, and, if undertaken, would have little chance of success,” accurately assessing that Hoxha’s security apparatus had consolidated sufficient control to repel external subversion.

Albanian countermeasures, including the arrest of over 150 Yugoslav agents and consolidation of 3,600 indigenous counterintelligents, resulted in the failure of Operation Valuable by 1956.

The operation’s collapse forced Yugoslav strategic reorientation towards the West yet simultaneously engendered Serbian resentment of Albanian assertiveness along the southern border, presaging future Kosovo tensions.

Concurrently, the Yugoslav state suppressed anti-communist insurgencies (1944–1960s) that persisted from wartime Chetnik and Ustaše remnants.

The Ozren and Koča operations targeting Serbian Chetnik holdouts and Croatian nationalist cells entailed systematic executions and informant networks establishing patterns of state terror against ethnic particularism.

These liquidations consolidated communist party control yet simultaneously embedded cycles of vendetta within Serbian and Croat communities, creating memorial cultures of victimhood that would be revived and weaponised by nationalist elites during the 1990s.

Milošević and Tuđman consciously invoked these purges to legitimate their own ethnic mobilisation, framing post-1991 conflicts as continuations of historical struggles rather than novel episodes of nationalist warfare.

Wars of Dissolution: The 1991–2001 Decade of Ethnic Disintegration

The Ten-Day War (27 June–7 July 1991)

Slovenia’s declaration of independence on 25 June 1991 triggered the first Yugoslav military response, yet the conflict’s brevity reflected strategic calculations by Serbian-dominated JNA leadership.

The Yugoslav People’s Army, though nominally a federal institution, had been progressively “Serbified” as Croats, Slovenes, Kosovar Albanians, and Bosniak officers departed.

Slovenian Territorial Defence Forces, augmented by police units, blockaded JNA barracks and disabled Yugoslav aircraft at Brnik airport. The Holmec border crossing became the conflict’s symbolic flashpoint, with Slovenian forces capturing JNA soldiers and repelling counteroffensives.

Slobodan Milošević himself stated in archival footage that he opposed deploying the JNA in Slovenia, preferring instead to concentrate forces in Croatia where Serbian populations and territorial claims were substantial.

After the Brioni Accords of 7 July mandated JNA withdrawal and three-month suspension of independence, Slovenia’s ethnically homogeneous composition rendered it strategically irrelevant to Serbian irredentism.

This outcome paradoxically enabled Slovenia’s peaceful secession and subsequent prosperity as a regional economic leader, whilst emboldening Croatian nationalists to pursue analogous separation and exposing the federation’s fundamental inability to manage pluralistic state dissolution.

The Croatian War of Independence (1991–1995)

Croatia’s declaration of independence on 25 June 1991 proved far bloodier than Slovenia’s equivalent, for the republic contained approximately 600,000 ethnic Serbs—predominantly concentrated in Krajina (a crescent-shaped territory across inland Croatia)—and substantial Serb minorities in eastern Slavonia and bordering Serbia proper.

The Log Revolution (August 1990) in Krajina constituted the conflict’s initial phase, wherein Serbian barricades and militia mobilisation attempted to prevent Croatian constitutional changes that reconstituted the republic as a nation-state rather than a multi-ethnic federation.

Key developments accelerated the military spiral: the Pakrac Clash (March 1991) saw JNA units deploying alongside Serb paramilitaries to contest Croatian military redeployment; the Plitvice Lakes incident (March 1991) resulted in the first fatal casualties; the Borovo Selo killings (May 1991) claimed 12 Croatian national guardsmen.

By August 1991, the battle for Vukovar—a medieval Danube town symbolically central to Croatian identity—commenced, lasting 87 days and reducing the city to rubble.

Serbian forces systematised ethnic cleansing across captured Krajina territory, displacing approximately 300,000 Croats whilst expelling 150,000–200,000 Serbs in reciprocal cleansings during Operations Flash (May 1995) and Storm (August 1995).

Operation Flash, executed 1–3 May 1995, represented a tactical Croatian offensive recovering a 558-square-kilometre salient near Okučani. The operation achieved its objectives, with 42 Croatian soldiers and policemen killed against disputed casualty figures of 188–283 Serbs (depending on source); 1,000–1,200 Serbs were wounded.

The conflict’s decisive phase occurred with Operation Storm (4–7 August 1995), the largest European land battle since World War II.

Croatian Army forces, augmented by special police and supported by the Bosniak-held Bihać pocket, advanced across a 630-kilometre front against the self-declared proto-state Republic of Serbian Krajina.

The RSK military collapsed with minimal organised resistance, affording Croat forces rapid capture of the Krajina capital Knin by 7 August. Approximately 211 Croatian military personnel and 42 civilians were killed, whilst Serbian sources disputed casualty figures, ranging from official Croatian claims of 526 Serb deaths to alternative estimates including larger civilian components.

The operation’s strategic importance transcended its immediate territorial recovery: it decisively altered the military balance in Bosnia and Herzegovina by enabling Croatian intervention alongside Bosniak forces, fundamentally degrading Serbian military capacity in the broader Yugoslav theatre.

The cumulative Croatian war toll was devastation: 12,131 Croat deaths (8,100 civilian), 33,043 injured, 2,251 missing in action, alongside 6,780 Serbs in Croatia killed or missing. Ethnic cleansing displaced 220,000 Croats and 300,000 Serbs, rendering the war one of Europe’s largest displacement events since 1945.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia later indicted multiple Croatian commanders including General Ante Gotovina, though acquittals and conviction disputes have remained contentious within Serbian and Croatian historical narratives.

The Bosnian War (1992–1995)

Bosnia and Herzegovina, the federation’s most ethnically heterogeneous republic, became the crucible for systematic genocide.

The republic’s 1991 census revealed 44% Bosniak (Muslim) plurality, 32.5% Serbs, and 17% Croats, distributed unevenly across the territory, with Serb-majority regions clustered in eastern enclaves and Croat populations concentrated in western Herzegovina. Following Slovenia’s and Croatia’s secessions, Bosniak-led republican authorities held a referendum on 29 February 1992 whereby 63% voted for independence.

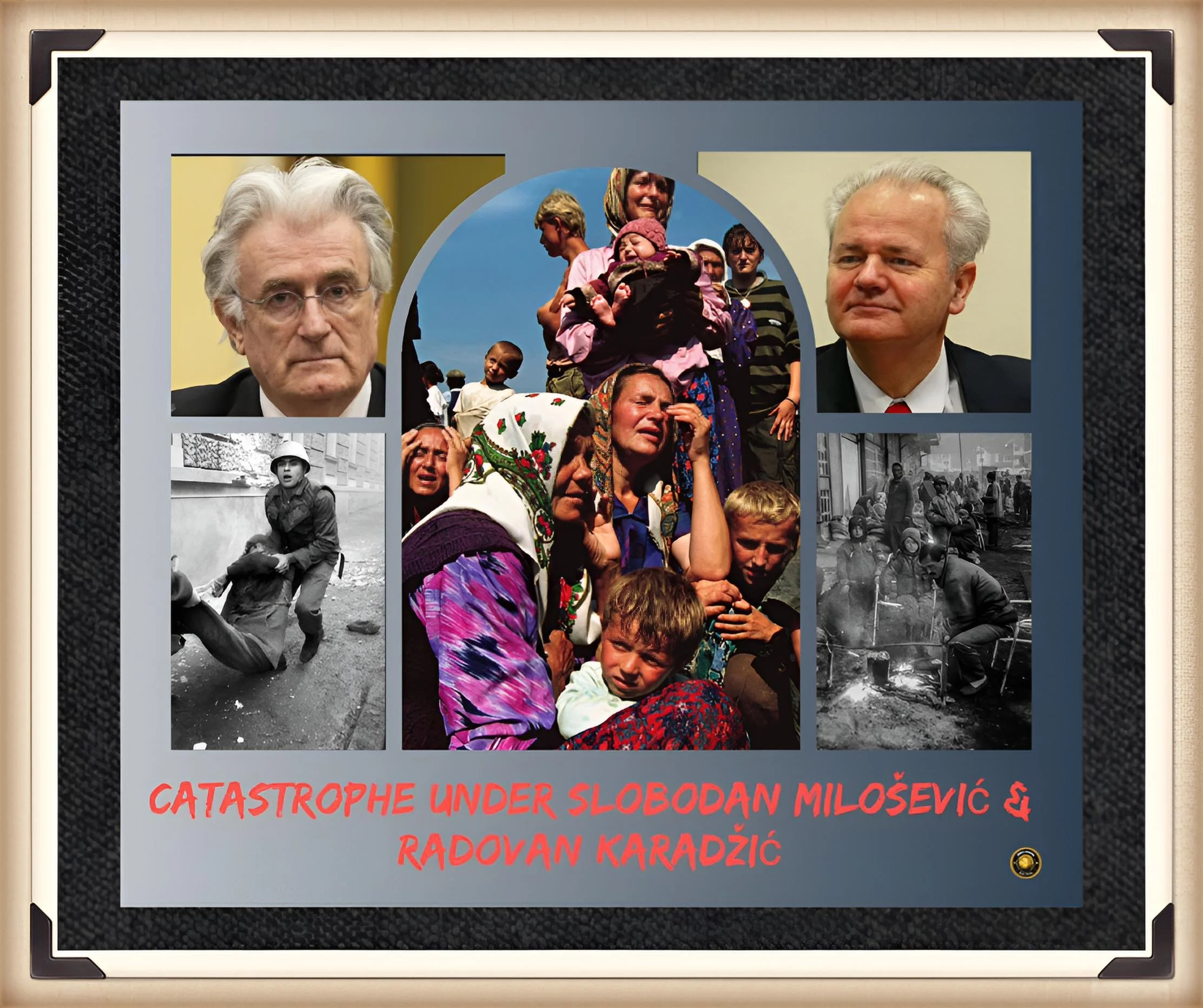

Bosnian Serb political leadership, backed by Slobodan Milošević’s Serbian government and supplied by the JNA, rejected the referendum’s legitimacy. Within weeks of Bosnia’s 1 March independence declaration, Serbian paramilitary forces and JNA units launched offensives designed to partition Bosnia into ethnically “cleansed” zones.

The Bosnian Serb leadership, principally Radovan Karadžić (political commander) and Ratko Mladić (military commander), implemented systematic ethnic cleansing and genocide.

The siege of Sarajevo, lasting 1,425 days from March 1992 to February 1996, subjected the Bosniak-majority capital to continuous artillery bombardment and sniper fire, killing approximately 5,000–10,000 civilians, predominantly from prolonged starvation and exposure.

Key massacres epitomised the war’s genocidal character: the Prijedor massacres (1992) eliminated Bosniak intellectuals and professionals; the Omarska, Trnopolje, and Keraterm detention camps held thousands in subhuman conditions; the Srebrenica massacre (July 1995) constituted the war’s singular most atrocious episode.

The Srebrenica genocide occurred when the Bosnian Serb Army under Ratko Mladić captured the UN-designated “safe area” on 11 July 1995.

United Nations Protection Force commander Dutch Colonel Thom Karremans, commanding merely 370 lightly armed peacekeepers, negotiated the surrender of approximately 5,000 civilians sheltering at the UN compound in exchange for the release of 14 Dutch peacekeepers held by Bosnian Serbs.

Over the ensuing days, Mladić’s forces systematically separated Bosniak men and boys aged 13 to 77 from their mothers, wives, and sisters. Between 11 and 18 July, approximately 8,000–8,400 men and boys were murdered in fields, schools, and warehouses surrounding Srebrenica.

The Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo identified 8,372 individual victims through meticulous documentation and DNA analysis, establishing that 83% were civilians.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia rulings in 2004 and International Court of Justice determinations in 2007 legally confirmed the Srebrenica massacre as genocide—the first such determination within Europe since World War II.

Beyond Srebrenica, systematic rape constituted an intentional genocidal mechanism. Between 20,000 and 50,000 Bosniak women endured sexual violence perpetrated by Bosnian Serb, Croat, and Bosniak forces, though Serbian forces conducted the overwhelming majority of these assaults within organised camp systems.

The International Criminal Tribunal prosecuted rape as genocide, marking the first tribunal to establish sexual violence as instrumentally genocidal rather than merely incidental to warfare.

The war’s human toll encompassed approximately 100,000 deaths, with research by the Research and Documentation Center in Sarajevo establishing 101,040 persons killed from 1991 to 1996.

The breakdown revealed 62,013 Bosniak casualties (31,107 civilian, 30,906 soldier), 24,953 Serb casualties (4,178 civilian, 20,775 soldier), and 8,403 Croat casualties (2,484 civilian, 5,919 soldier).

These figures underscore the war’s explicitly genocidal targeting of Bosniaks, whose civilian casualty proportion vastly exceeded their military losses—a demographic signature of organised extermination.

The Dayton Accords, initialled on 21 November 1995 and formally signed on 14 December 1995 in Paris, ended active hostilities through a negotiated partition masquerading as a unitary state.

The agreement preserved Bosnia as a single nation yet partitioned it into two entities of radically asymmetrical power: the Bosniak-Croat Federation (51% of territory) and Republika Srpska (49% of territory).

Each entity retained paralysing veto powers over central institutions, effectively institutionalising ethnic separation whilst maintaining nominal state unity.

The accords established the Office of the High Representative, empowered to impose legislation when parliamentary consensus proved unattainable—a mechanism of external governance unprecedented in post-1945 European state reconstruction.

The Kosovo War (1998–1999)

Kosovo’s status as an autonomous province within Serbia proved a flashpoint throughout Yugoslav history. In 1989, Milošević revoked Kosovo’s autonomy, triggering Albanian nationalist resistance and the emergence of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in 1995–1996.

Initial KLA insurgency involved ambushes of Serbian security forces, whilst Milošević’s regime responded with disproportionate counter-insurgency operations characterised by civilian targeting and extrajudicial killings. By 1998, the conflict escalated into open warfare, with Yugoslav security forces conducting large-scale offensives against KLA sanctuaries in Kosovo’s Drenica valley.

International diplomatic intervention centred on the Rambouillet Accords, through which NATO mediators presented Yugoslavia with an ultimatum: permit NATO military occupation of Kosovo (Appendix B), withdraw Yugoslav security forces, and grant Kosovo substantial autonomy.

Milošević’s government rejected these terms as unacceptable infringements on Serbian sovereignty. In response, NATO launched Operation Allied Force on 24 March 1999, implementing a 78-day aerial bombing campaign without United Nations Security Council authorisation (Russia and China possessed veto power, rendering Security Council approval impossible).

The campaign targeted Yugoslav military installations, command centres, bridges, and ultimately civilian infrastructure including factories, hospitals, and power plants.

NATO forces flew 400 sorties on the first night alone, introducing B-1 bombers in phase two operations and maintaining an intensive campaign averaging 50 strikes nightly by campaign conclusion.

NATO’s bombing precipitated a catastrophic humanitarian crisis: Yugoslav security forces, freed from conventional military threat through Serbian air defence degradation, accelerated ethnic cleansing of Kosovo’s Albanian majority population.

Approximately 862,000 Kosovar Albanians fled or were forcibly expelled into Albania and Macedonia, creating humanitarian emergencies in bordering nations.

NATO casualty figures recorded 10,317 civilians killed or missing, with 85% constituting actual civilian fatalities rather than ambiguous combat-related deaths.

Yugoslav official figures claimed 1,500 to 2,131 combatant deaths, though independent verification proved impossible given NATO’s refusal to conduct damage assessments.

The bombing campaign targeted Serbian economic and civilian infrastructure with deliberate intent to degrade civilian morale and coerce political capitulation—a doctrine of strategic bombing morally and legally contentious despite NATO’s humanitarian framing.

The Kumanovo Treaty (9 June 1999) concluded hostilities following Milošević’s capitulation. Yugoslav forces withdrew from Kosovo, permitting the deployment of the Kosovo Force (KFOR), a NATO-led multinational peacekeeping contingent. The treaty established a demilitarised buffer zone along Kosovo’s border with Serbia proper, restricting Yugoslav security forces to a 5-kilometre perimeter.

The United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) was established as the sole civilian authority, administering Kosovo’s governance until resolution of its final status.

This arrangement, ostensibly temporary, effectively constituted international trusteeship over a Serbian-claimed territory, fundamentally violating Serbian sovereignty and engendering perpetual resentment within Serbian political culture.

The Preševo Valley and Macedonian Insurgencies (1999–2001)

Kosovo’s nominal settlement precipitated spillover insurgencies in ethnically Albanian enclaves within Serbia and Macedonia. The Preševo Valley, abutting Kosovo’s border with Serbia proper, erupted in 1999 as the Liberation Army of Preševo, Medveđa and Bujanovac (UÇPMB) launched attacks against Serbian police and civilians. Approximately 1,160 attacks occurred throughout 1999–2001, involving ambushes, mortar barrages from Kosovar sanctuaries, and destabilisation of border communities.

Yugoslav security forces responded with checkpoints and patrols, whilst seeking KFOR mediation in suppressing UÇPMB bases within Kosovo’s demilitarised zone. By 2001, approximately 400 UÇPMB guerrillas agreed to disarm in exchange for Yugoslav government pardons, with commander Shefket Musliu surrendering to KFOR on 26 May 2001.

This conflict, though less publicised than Kosovo’s war, demonstrated the contiguity of Albanian nationalist aspirations across former Yugoslav territory.

The 2001 Macedonian insurgency, initiated in January 2001, represented the most serious threat to the only former Yugoslav republic that had achieved peaceful independence in 1991. The National Liberation Army (NLA), composed substantially of Kosovo War and Preševo Valley veterans, attacked Macedonian security forces in ethnically mixed northern municipalities.

The conflict escalated through spring 2001, with NATO serving as intermediary between Macedonian authorities and NLA negotiators. The Ohrid Agreement (13 August 2001) concluded hostilities through constitutional amendments granting ethnic Albanians minority language rights, proportional representation in security forces, and administrative decentralisation in Albanian-majority municipalities.

Though casualties remained limited compared to other Yugoslav conflicts, the insurgency’s rapid resolution through international mediation and minority rights guarantees offered a template for conflict containment—notably absent during earlier Yugoslav fragmentation.

Causes and Catalytic Factors: The Interconnection of Economics, Institutions, and Ethno-Nationalism

The Yugoslav wars did not emerge from primordial ethnic hatreds suddenly unleashed following communism’s collapse. Rather, they resulted from the convergence of structural institutional failures, exogenous economic shocks, and the calculated mobilisation of ethnic identity by competitive elites. Understanding this causality is essential for comprehending parallel contemporary crises.

Tito’s death on 4 May 1980 removed the singular supra-national figure whose charisma, revolutionary legitimacy, and demonstrated willingness to suppress nationalist elites had held the federation together for 35 years.

The Yugoslav federation inherited approximately $20 billion in external debt at Tito’s passing—substantial for a middle-income socialist state—yet the debt burden escalated dramatically during the 1980s as global interest rates rose, commodity prices declined, and Yugoslavia’s export sectors contracted.

The International Monetary Fund’s intervention in 1987, implementing “shock therapy” austerity programmes, fundamentally destabilised Yugoslav federalism. IMF-mandated reductions in government expenditure, currency devaluation to enhance export competitiveness, and restrictions on credit expansion collectively precipitated domestic demand collapse.

Unemployment surged whilst inflation accelerated beyond the state’s capacity to manage through monetary policy. By the late 1980s, Yugoslavia experienced hyperinflation exceeding 100% annually, eviscerated real wages, and widespread economic desperation.

This economic trauma distributed itself unevenly across republics, exacerbating existing fiscal asymmetries.

Slovenia and Croatia, ethnically homogeneous and geographically proximate to Western European markets, possessed industrial exports and tourism revenue insulating them from systemic Yugoslav economic failure.

Conversely, Serbia, Bosnia, Macedonia, and Montenegro—economically subordinate regions historically subsidised through federal redistribution—experienced catastrophic impoverishment. Slovenia’s elites perceived continued federation as entrapment within a sinking ship, wherein their economic surpluses were transferred to impoverished republics.

This defensive mobilisation against economic loss transformed into secessionist politics: if Slovenia remained federated, its wealth would hemorrhage perpetually to subsidise Serbian military expenditures and Montenegrin clientelism. Separation promised economic sovereignty and Western European integration.

Serbian elites articulated fundamentally opposed grievances. The 1974 Constitution had devolved substantial autonomy to Kosovo and Vojvodina, Serbia’s two autonomous provinces, effectively reducing Serbia’s internal control over 30% of its nominal territory.

Serbian nationalists, particularly within the Serbian Orthodox Church and military intelligentsia, perceived this constitutional arrangement as a humiliation imposed by Tito’s cosmopolitanism.

Milošević’s rise to power in 1986, consolidated through his February 1989 speech at the Battle of Kosovo Field’s 600th anniversary, explicitly invoked Serbian victimhood narratives dating to Ottoman conquest and interwar Serb-dominated centralisation. His 1989 revocation of Kosovo’s autonomy, followed by similar measures against Vojvodina, represented an attempt to reassert Serbian control over federal institutions before the federation itself dissolved.

These opposing impulses—Western republican desire for separation and Serbian desire for recentralisation—rendered compromise impossible under conditions of economic disintegration.

The rotating federal presidency, designed by Tito to ensure ethnic equilibrium, proved paralysing as republics increasingly refused to transfer executive authority to representatives from opposing ethnic blocs.

By 1990–1991, the federation’s deliberative mechanisms had collapsed entirely, replaced by unilateral declarations of independence by Slovenia (25 June 1991) and Croatia (25 June 1991). Yugoslavia’s dissolution was not invitable—it reflected specific decisions by identifiable elites.

However, the conditions precipitating these decisions—fiscal imbalance, constitutional ambiguity, economic desperation, and the absence of supra-national legitimacy post-Tito—rendered federation preservation extraordinarily difficult.

International factors accelerated dissolution. German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher’s December 1991 announcement of Germany’s intention to recognise Slovenian and Croatian independence, made without EU consensus or Yugoslav consent, precipitated cascade effects.

Slovenia’s and Croatia’s international recognition, coupled with German encouragement of Bosnian independence, signalled to Serbian populations within these republics that their security could no longer be assured through Yugoslav federalism. If Croatia and Slovenia were to become independent nation-states, Serbs within their territories would transition from federal citizenship to minority status within hostile ethno-nationalist republics.

This perception justified, in Serbian nationalist reasoning, pre-emptive territorial conquest and ethnic cleansing to establish contiguous Serbian territories that could either remain federated with Serbia or secede and rejoin the Serbian nation-state.

Humanitarian Toll and International Justice

The Yugoslav Wars’ human consequences were staggering. The International Center for Transitional Justice, the Humanitarian Law Center, and other organisations cite death tolls ranging from 130,000 to 140,000 persons across all conflicts (1991–2001).

These figures encompassed combatants and civilians, with conservative estimates establishing that 60–70% of fatalities were civilian populations deliberately targeted through ethnic cleansing, siege warfare, and systematic genocide.

Approximately 2 million persons were displaced from their homes, constituting more than 10% of the former Yugoslav population—a displacement rate exceeded in post-1945 Europe only by the Partition of India and the Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923.

Systematic rape emerged as an instrumentalised genocidal mechanism, particularly within Bosnian enclaves. Between 20,000 and 50,000 women, predominantly Bosniaks, were subjected to sexual violence within camps operated by Bosnian Serb, Croat, and occasionally Bosniak forces.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia prosecuted rape perpetrators and established legal precedent recognising systematic sexual violence as constituting genocide when deployed intentionally to prevent reproduction within targeted ethnic groups—a determination that fundamentally altered international humanitarian law.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, established by United Nations Security Council resolution in 1993, prosecuted 161 individuals indicted for war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. Slobodan Milošević faced 66 counts spanning Kosovo, Croatia, and Bosnia, though his death in 2006 prevented conclusive tribunal determination.

Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić were convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity, receiving life sentences. Ante Gotovina, a Croatian general, was acquitted despite initial conviction, highlighting the tribunal’s contestations and the incomplete international consensus regarding criminal accountability.

Serbian civil society organisations have noted the tribunal’s disproportionate focus on Serbian perpetrators, with Serbs and ethnic Serbs receiving combined sentences totalling 1,150 years whilst alleged Croat and Bosniak perpetrators received sentences totalling approximately 55 years—a disparity engendering persistent resentment within Serbian political culture and complicating reconciliation efforts.

The Dayton Accords established mechanisms for transitional justice, mandating compensation for displaced persons and property restitution. However, implementation proved incomplete and halting. Approximately 2 million persons were displaced; fewer than 1 million have returned to their pre-war residences.

Property disputes remain unresolved in substantial percentages, with returnees encountering hostility and economic discrimination from ethnic majorities in their destinations.

This incomplete physical reconciliation—displacement transformed into permanent migration—has meant that younger generations, particularly those born during wars or in post-war diaspora communities, maintain tenuous connections to ancestral homelands, rendering traditional narratives of ethnic territorial claims increasingly abstracted from lived experience.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: The Cascade of Institutional Collapse

The Yugoslav wars emerged from a causal chain wherein each antecedent condition necessitated subsequent institutional degradation.

Tito’s charismatic federal authority suppressed latent ethnic mobilisation through both coercive capacity and revolutionary legitimacy—the latter deriving from the Partisan movement’s multiethnic anti-fascist narrative. Upon his death, this legitimacy evaporated; the communist party lost moral claim to transcend particularism, yet retained monopolistic institutional control. This contradiction proved unsustainable.

Concurrently, the 1974 Constitution’s extreme devolution of power to republics and autonomous provinces had been intended to perpetuate federalism through distributed institutional checks against any single republic’s hegemony. Yet this mechanism functioned only whilst supranational legitimacy—embodied in Tito and ideology—persisted. Once both dissipated, the constitution became an invitation to competitive ethno-nationalist mobilisation.

The IMF’s 1987 structural adjustment programme functioned as a catalyst accelerating this process. Austerity measures contracted aggregate demand within Yugoslavia’s integrated economy, yet their effects distributed unevenly across republican economies.

Slovenia and Croatia could leverage Western trade networks and tourism; Serbia, Bosnia, and Macedonia faced accelerating immiseration.

This fiscal divergence engendered political divergence: prosperous republics perceived continued federation as loss, whilst impoverished republics perceived separation as abandonment. No political compromise could satisfy both constituencies.

Milošević’s rise and ethno-nationalist mobilisation within Serbia transformed potential economic disputes into existential security competitions. His rhetoric invoked historical Serbian victimhood (1389 Battle of Kosovo, Ottoman domination, Austro-Hungarian annexation) to legitimate contemporary Serbian nationalism.

This mobilisation resonated within Serbian populations, particularly in peripheral regions, generating political support for Milošević’s recentralisation agenda. However, identical nationalism animated Croatian (Franjo Tuđman) and Slovenian (Milan Kučan) leaders, each invoking ethnic self-determination narratives.

The result was a cascade of reciprocal ethnic mobilisation wherein each republic’s nationalist elite, seeking to outbid competitors and consolidate domestic support, escalated rhetoric and ultimately deployed military force.

The effect was institutional collapse culminating in genocide. Ethnic cleansing represented an attempt to reorder territorial control to match ethnic claims: if Croats claimed Croatia, non-Croats must be expelled; if Serbs claimed substantial Bosnian enclaves, non-Serbs inhabiting these territories must be displaced or exterminated.

The genocide emerged not from spontaneous primordial hatreds but from calculated strategic decisions by military commanders and political leaders seeking to consolidate territorial control and impose ethnic homogeneity on contested lands.

The International Criminal Tribunal’s indictments and convictions establish this causality beyond reasonable doubt: systematic planning, implementation hierarchies, and resource allocation preceded atrocities, refuting narratives of spontaneous ethnic violence.

Lessons Learned: Federal Fragility and Institutional Resilience

Yugoslavia’s dissolution furnishes comprehensive lessons regarding the fragility of polyethnic federations and the prerequisites for their preservation.

Foremost amongst these insights is that charismatic centralised authority, whilst capable of suppressing ethnic particularism, proves unsustainable as a foundational legitimacy principle.

Tito’s federation depended upon a singular individual whose revolutionary credentials transcended ethnic identity; upon his death, no successor possessed analogous legitimacy.

This lesson suggests that durable federations require supranational institutional mechanisms and ideological frameworks capable of persisting across generational transitions.

The European Union represents an explicitly post-national institutional architecture designed to prevent nationalist recreations of Yugoslavia-style dissolutions; its expansion toward the Balkans reflects this cautionary learning.

Secondly, fiscal asymmetries between constituent units create incentive structures favourable to secession. If prosperous republics perceive themselves as subsidising impoverished counterparts, separation becomes economically rational.

The 1974 Constitution’s federal redistribution mechanisms, which transferred Slovenian and Croatian surpluses to Belgrade’s centralized military establishment and poorer republics, generated accumulating resentment. Durable federations require enforceable mechanisms ensuring that fiscal transfers occur through transparent processes perceived as legitimate by all constituent units.

The United States federal system, for instance, legitimates fiscal redistribution through explicitly democratic processes and constitutional constraints on central government taxing power; the European Union coordinates transfers through supranational parliamentary bodies.

Yugoslavia lacked such legitimating mechanisms—redistribution occurred through opaque federal apparatus controlled by Serbian-dominated parties.

Thirdly, constitutional ambiguity regarding the relationship between ethnic and territorial identity proves catastrophic. The 1974 Constitution established republics nominally corresponding to ethnic nations (Slovenia as Slovene nation, Serbia as Serbian nation, etc.) yet simultaneously granted autonomy to ethnic minorities within republics (Kosovars within Serbia, Serbs within Croatia).

This ambiguity generated irreconcilable claims: if nations possessed the right to self-determination, which spatial unit embodied the nation—the republic or the ethno-cultural group?

Dayton’s consociational framework attempted to resolve this ambiguity through institutionalised ethnic quotas, explicitly recognising ethnic groups as the fundamental political units. Whilst this mechanism has prevented renewed military conflict, it has simultaneously entrenched ethnic divisions by constitutionalising ethnicity as the paramount identity category.

Fourthly, early intervention in incipient conflicts proves vastly more cost-effective than post-conflict reconstruction. The Yugoslav wars’ humanitarian, material, and institutional costs (140,000 deaths, $200 billion in economic destruction, generational trauma) vastly exceeded the modest diplomatic investment required to address grievances before 1991.

International actors’ failures to impose negotiated federalism reforms, fiscal redistribution mechanisms, and constitutional clarity between 1980 and 1990 reflected misplaced confidence that Yugoslavia could persist unchanged. Subsequent interventions (NATO bombing in Kosovo, IFOR deployment in Bosnia) occurred reactively, addressing symptoms rather than causes.

Fifthly, international recognition of secessionist claims, absent guarantees for minority protection within seceding entities, precipitates displacement and ethnic conflict. German recognition of Slovenian and Croatian independence, followed by European Union accession, signalled to Serb minorities within these republics that their security was forfeit.

Without guarantees of minority rights, collective self-determination proved indistinguishable from ethnic cleansing. Subsequent international instruments (the Ohrid Agreement’s minority rights guarantees, EU conditionality requiring minority protections) reflect this learning, though their efficacy remains contested.

Contemporary Geopolitical Implications

Yugoslavia’s dissolution casts long shadows across contemporary geopolitical contests.

The Ukraine conflict exhibits structural parallels: a multi-ethnic federal polity (the Soviet Union) collapsed, engendering competing territorial claims between a hegemonic core (Russia) seeking recentralisation and peripheral republics (Ukraine) pursuing secession.

Kyiv’s 2022 NATO proximity, analogous to Bosnia’s 1992 EC recognition, catalysed Russian intervention framed in analogous language to Milošević’s—protecting co-ethnic populations and resisting external encroachment on Russian spheres of influence.

The analogy remains imperfect—Ukraine possesses nuclear-armed allies; Serbia did not—yet the causal grammar mirrors Yugoslav patterns.

Gaza’s humanitarian crisis, whilst distinct in its colonial dimensions, echoes Sarajevo’s siege warfare and Srebrenica’s systematic genocidal intent.

International inability to impose negotiated settlement, combined with armed external interventions (Israeli strikes, Iranian missile barrages), parallels NATO’s unsuccessful diplomatic initiatives preceding Kosovo bombing.

The displacement of Palestinians and destruction of civilian infrastructure evokes Yugoslav patterns of ethnic displacement and infrastructure targeting.

Ethiopia’s Tigray conflict recapitulates Bosnian ethnic cleansing: federal authority’s attempt to suppress subnational autonomy movements precipitated famine, displacement, and documented genocide by federal forces and allied militias.

International responses—tepid condemnation, modest sanctions, limited humanitarian access—mirror the Security Council’s paralysis during Bosnian genocide when Russian and Chinese vetoes prevented forceful international intervention.

NATO’s 1999 bombing campaign, executed without UN Security Council authorisation, established precedent for unilateral humanitarian intervention that subverts international law.

This precedent proved contentious: Russian and Chinese strategists cite NATO’s Kosovo intervention to justify their own security sphere assertions in post-Soviet space.

Milošević’s defiance of Rambouillet Accords’ territorial occupation demands anticipated Putin’s analogous rejection of NATO’s expansion into former Soviet republics.

The lesson—that humanitarian justifications for military intervention, whilst potentially legitimate, generate reciprocal strategic competition from excluded powers—fundamentally shaped post-Yugoslav geopolitics.

The European Union’s Balkans enlargement strategy, grounded in the premise that economic integration and institutional harmonisation prevent renewed conflict, reflects Yugoslav lessons applied prospectively.

EU conditionality requiring democratic governance, minority rights protections, and regional reconciliation has prevented renewed military conflict in the successor Balkans. Montenegro faces EU accession completion by 2026, whilst Albania, Serbia, and North Macedonia progress through negotiation processes.

Yet the strategy’s incomplete success—persistent ethnic tensions, contested historical narratives, unresolved war crimes accountability, incomplete refugee returns—indicates that institutional design alone cannot overcome generational trauma and embedded territorial claims.

Serbia’s ongoing geopolitical fence-sitting—simultaneously seeking EU membership (requiring NATO alignment and minority protections) and maintaining Russian alliance (precluding NATO involvement and demanding Serbian sphere primacy)—reflects the Yugoslav wars’ unresolved legacy.

Belgrade’s refusal to extradite indicted Bosnian Serb generals to international tribunals, despite EU conditionality demanding such cooperation, signals persistent nationalist resistance to accountability narratives.

Conversely, Bosnian and Croatian courts have prosecuted their own nationals, partially addressing the ICTY’s perceived ethnic bias. This asymmetric accountability complicates reconciliation and perpetuates grievance cycles.

Conclusion

Srebrenica to Sarajevo: The Hidden Parallels Between Yugoslavia’s 1990s Wars and Contemporary Crises in Ukraine, Gaza, and Ethiopia

Yugoslavia’s decade-spanning martial odyssey—encompassing ten distinct wars, 140,000 deaths, systematic genocides, and displacement of over two million persons—epitomises the catastrophic consequences attending the dissolution of polyethnic federations bereft of supranational institutional mechanisms, ideological cohesion, and fiscal equity mechanisms.

The federation’s fragmentation was neither inevitable nor spontaneous: it resulted from identifiable causal chains wherein Tito’s death eliminated supra-national legitimacy, constitutional ambiguity regarding ethnic self-determination engendered competing territorial claims, economic crisis precipitated by IMF adjustment programmes exacerbated fiscal disparities, and nationalist elites consciously mobilised ethnic grievance to consolidate political power.

The wars’ humanitarian toll—genocide at Srebrenica, systematic rape in Bosnia, displacement of Albanian populations from Kosovo, and endemic vendetta cycles within successor states—represents Europe’s gravest humanitarian catastrophe since World War II.

Yet Yugoslavia’s tragedy furnishes actionable lessons for contemporary policymakers confronting analogous challenges.

Durable federations require supranational legitimacy transcending charismatic individuals, transparent and equitable fiscal redistribution mechanisms, constitutional clarity regarding the relationship between ethnicity and territory, and international frameworks protecting minorities within seceding entities.

Early diplomatic intervention addressing incipient conflicts proves vastly more cost-effective than post-conflict reconstruction.

Humanitarian intervention, whilst potentially justified, generates strategic backlash from excluded powers; legitimacy through Security Council mandates proves preferable to unilateral intervention.

Regional integration through supranational institutions (EU model), combined with conditionality requiring democratic governance and minority protections, reduces conflict probability without imposing formal federation.

The successor Yugoslav states’ contemporary trajectories—Slovenia and Croatia’s EU integration, Bosnia’s consociational deadlock, Serbia’s geopolitical fence-sitting, and North Macedonia’s minority protections—reflect differential success in institutional learning.

Thirty years post-dissolution, the region remains psychologically scarred by unresolved grievances, contested historical narratives, and incomplete accountability for genocide.

Should multipolar competition intensify and international stability institutions weaken, the Balkans remain vulnerable to renewed escalation.

Conversely, sustained EU integration and NATO enlargement, combined with generational transition beyond those bearing direct war memory, offer pathways toward stabilisation.

The central imperative remains preserving institutional mechanisms preventing recursive ethnic mobilisation and territorial revisionism—lessons Yugoslavia purchased at devastating human cost.