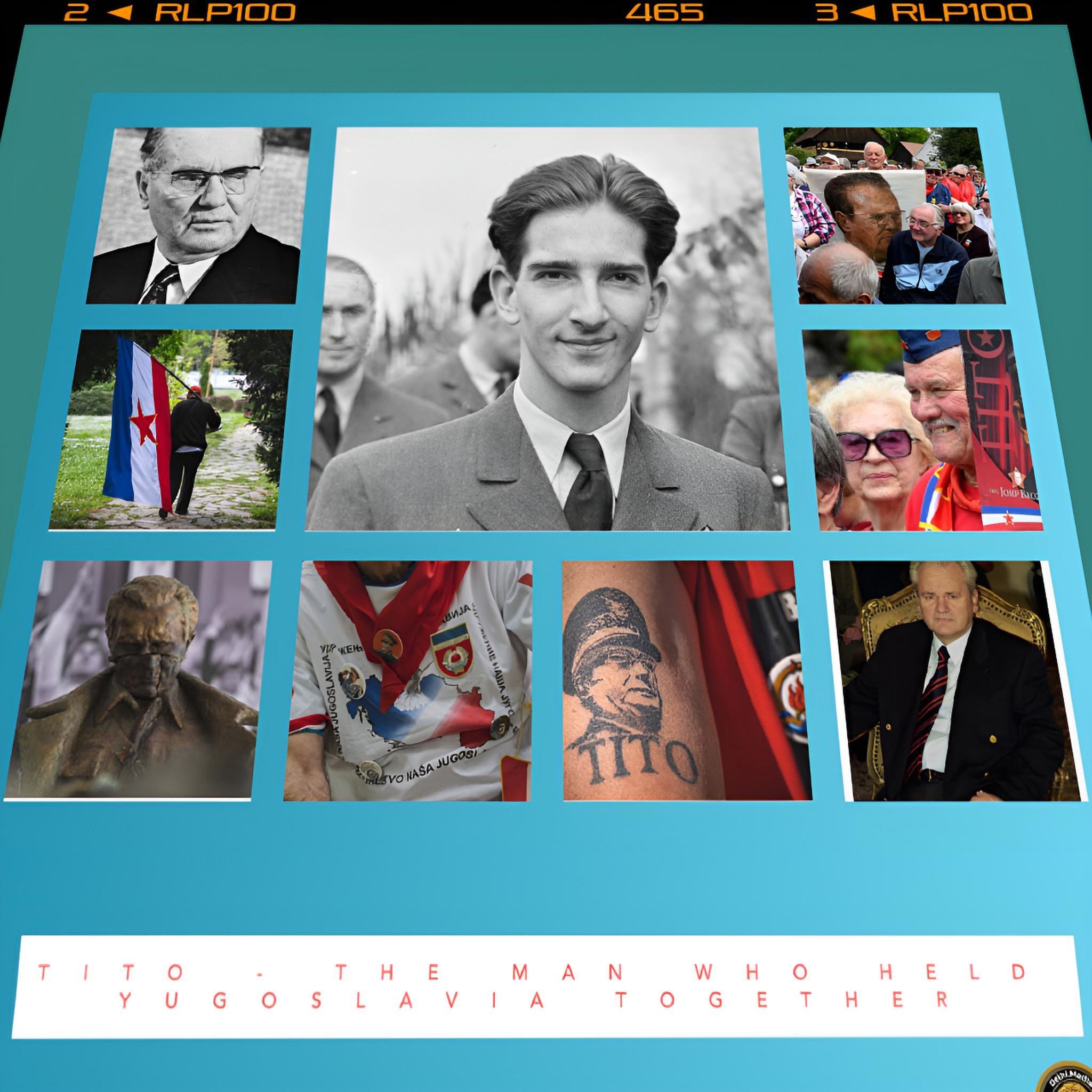

Josip Broz Tito - The Man Who Held Yugoslavia Together—And Why His Successors Couldn’t” - Part III

Executive Summary

Josip Broz Tito’s rule over Yugoslavia from 1945 to 1980 presents a paradoxical historical case that defies simple categorization. His five decades in power produced remarkable socio-economic achievements—rapid industrialization, universal literacy expansion, healthcare advancement, and independence from Soviet domination—yet simultaneously established structural vulnerabilities that made the Yugoslav state fundamentally dependent on his personalized authority.

Tito successfully managed a fractious federation of competing ethnic nations through a combination of communist party monopoly, judicious decentralisation, and force, yet his governance model failed to resolve the underlying tensions it merely suppressed. The apparent stability of his era, though genuine in measurable economic and social metrics, rested upon institutional foundations so fragile that the system collapsed catastrophically within a decade of his death.

His legacy remains contested: a transformative moderniser who temporarily unified a historically fragmented region, or an autocrat whose concentration of power and ideological contradictions guaranteed Yugoslavia’s eventual dissolution.

Introduction

The question of whether Tito was “a good leader” necessitates clarity on evaluative criteria.

From a technical governance perspective, effectiveness encompasses both the achievement of stated objectives and the sustainability of institutional arrangements.

From an ethical standpoint, one must weigh authoritarian control against material prosperity and international influence.

From a historical perspective, the critical inquiry becomes whether Tito’s system produced durable stability or merely postponed inevitable conflicts.

Yugoslavia under Tito (1945–1980) achieved unprecedented economic growth, social modernisation, and geopolitical influence for a small Balkan state.

Yet within eleven years of his death, the country descended into Europe’s bloodiest conflict since World War II.

This fundamental contradiction—between apparent success and rapid failure—requires nuanced analysis rather than categorical judgment.

Historical Context and Rise to Power

Josip Broz Tito emerged from World War II as the leader of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (CPY) and the architect of partisan victory against Axis occupiers, an accomplishment that granted him exceptional legitimacy among Yugoslavs.

Unlike Eastern European communist leaders installed by Soviet tanks, Tito’s authority derived from indigenous military success and popular anti-fascist resistance. This distinction proved historically consequential.

The 1948 rupture with Stalin—a moment when Soviet pressure threatened to subordinate Yugoslavia to Moscow’s bloc discipline—became the founding mythology of Tito’s rule. He defied the Soviet leader when Stalin’s pressures threatened Yugoslav independence, resisting military intervention and economic isolation through resourcefulness and Western support.

This singular achievement became the cornerstone of his regime’s ideological legitimacy and distinguished Yugoslavia from the Soviet sphere, positioning it as a unique experiment in “national communism” and worker self-management.

The federal structure Tito adopted after 1945 represented both an ideological commitment and a pragmatic accommodation to Yugoslavia’s ethnic complexity.

The 1946 constitution established six republics (Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro) and two autonomous provinces within Serbia (Kosovo and Vojvodina), nominally coordinated by federal institutions.

Each republic possessed its own parliament, government structure, and armed forces, though party and security apparatus remained centralized.

This arrangement reflected Tito’s understanding that Yugoslav unity required acknowledging ethnic particularity rather than denying it. The Communist Party, however, retained absolute monopoly over political power, decision-making authority, and ideological orientation.

Key Achievements: Economic Modernization and Social Development

Industrial Transformation and Growth Performance

Yugoslavia achieved the most rapid economic expansion of any Eastern European state during the 1950s and 1960s. Between 1953 and 1960, industrial production expanded at 13.83 percent annually—a world record surpassing even Japan’s growth rate during that period.

Per capita GDP nearly quintupled between 1952 and 1979, representing a transformation of unprecedented scope in the Yugoslav context. This growth trajectory resulted from deliberate state investment in heavy industry, infrastructure, and structural modernisation—particularly the massive reallocation of labour from subsistence agriculture to manufacturing and services.

Tito’s government systematised this transition through systematic capital accumulation and sectorial shift. Between 1945 and 1980, the state constructed extensive transportation networks—railways, highways, tunnels—alongside factories, power plants, and mining operations.

Electrification, in particular, constituted a legacy achievement; by the 1960s, previously unelectrified villages across Yugoslavia gained access to modern energy infrastructure, fundamentally transforming rural living standards.

By 1952, industrial production had doubled and industrial output increased fivefold compared to pre-war levels, despite wartime devastation.

However, this growth model contained inherent structural weaknesses that would become apparent only after Tito’s death.

Growth during the 1970s relied increasingly on foreign borrowing rather than productive efficiency. Yugoslavia’s foreign debt grew at more than 17 percent annually during the final twenty years of Tito’s rule, rendering long-term economic sustainability dependent on continuous debt expansion.

The “golden seventies”—when consumption and living standards rose notably—were artificially sustained through loans that generated neither productive returns nor long-term capacity for debt service.

By 1983, Yugoslavia officially became bankrupt, though this reality was deliberately concealed from the population.

Education and Literacy Achievements

Perhaps the most unambiguously positive dimension of Tito’s rule lay in educational expansion and literacy advancement.

In 1921, the national illiteracy rate stood at 51.5 percent, ranging from 8.8 percent in Slovenia to 83.8 percent in Macedonia—a staggering disparity reflecting the underdevelopment of interior regions.

By 1961, the national illiteracy rate had fallen to 20 percent, and by 1981 to merely 0.8 percent in Slovenia (though 17.6 percent remained in Kosovo, indicating persistent regional inequality).

School attendance increased dramatically: 71 percent of Yugoslav children completed elementary school by 1953, and by 1981 this figure reached 97 percent.

This represented genuine mass literacy achievement, particularly significant given Yugoslavia’s pre-war developmental lag compared to Western Europe.

Educational expansion occurred alongside systematic healthcare improvements. Post-war Yugoslavia witnessed substantial reductions in mortality rates and expansion of medical infrastructure, with universal access to basic healthcare services becoming a defining characteristic of the socialist welfare state.

Regional disparities persisted even as overall health indicators improved substantially—disparities that reflected Tito’s federal investment strategy, which attempted to narrow (though never eliminate) developmental gaps between northern and southern republics.

Political Stability and the Illusion of Integration

The “Brotherhood and Unity” Ideology

Tito’s regime adopted the slogan “brotherhood and unity” as its founding ideological principle, but this formulation concealed rather than resolved fundamental contradictions.

The ideology emphasised mutual respect among nations and equality between ethnic groups, rather than the creation of a unitary Yugoslav national identity that would subsume ethnic particularism.

Historical analysis reveals that Tito deliberately discouraged identification with a supranational “Yugoslav” identity, preferring instead to maintain ethnic categories within a framework of communist party discipline and federal coordination.

In practice, “brotherhood and unity” functioned as a repressive enforcer of conformity. Individuals who emphasised their Croat, Serb, or other ethnic identity over Yugoslav belonging risked arrest and loss of civil rights.

This enforcement through coercion, rather than genuine ideological persuasion, meant that ethnic consciousness was merely driven underground rather than eliminated.

The Communist Party maintained extensive secret police apparatus, conducted purges of suspected nationalist elements, and imprisoned dissidents in notorious facilities such as Goli Otok (an island prison for political prisoners).

The regime understood itself as engaged in continuous struggle against “enemies of the state,” including not only fascist remnants but also anyone expressing doubts about Yugoslav unity or communist orthodoxy.

Suppression of National Movements

Two critical moments revealed the limitations of Tito’s integration project.

The Croatian Spring (1967–1971) emerged as a movement within the Communist Party of Croatia itself, initially centred on economic nationalism and demands for greater autonomy, but evolving into broader assertions of Croatian cultural and linguistic distinctiveness.

The movement reflected genuine grievances: Croatia, as the most developed republic, resented transferring resources to underdeveloped regions and believed its economic potential was being constrained by federal redistribution policies.

Tito responded by removing reformist Croatian communist leadership, purging younger cadres, and reasserting centralised control.

The movement was suppressed not through democratic debate but through party hierarchy and security apparatus deployment.

Similarly, Kosovo’s Albanian population—never integrated into the “brotherhood and unity” framework despite constituting an Albanian majority in the province—experienced systematic discrimination and periodic violent repression.

Albanian riots in 1968 and early 1970s were forcibly suppressed by federal security forces.

Tito deliberately denied Kosovo the status of a republic (as opposed to autonomous province), fearing both Serbian nationalist reactions and potential union with Albania.

This represented a conscious decision to maintain hierarchical status differentials among Yugoslav peoples, contradicting the official egalitarian ideology.

The Structural Weakness: Personalised Authority

Beneath surface stability lay a critical institutional vulnerability: Tito’s regime depended fundamentally on his personal authority rather than on robust institutional arrangements capable of surviving his departure.

Contemporary observers noted that “the force of his personality alone held his fragile government together.”

The 1974 Constitution attempted to address this problem by creating a system of “symmetrical federalism”—a collective presidency of eight regional representatives (from six republics and two autonomous provinces, plus a party chairman) that would rotate leadership annually after Tito’s death.

This elaborate succession mechanism reflected awareness that no single successor possessed sufficient legitimacy to maintain his centralised control.

Yet this constitutional innovation inadvertently weakened the federal centre by diffusing authority among regional power brokers, each representing competing republican interests.

The federal government could not enforce discipline over republics, and republics increasingly pursued independent economic strategies and foreign relations.

By the 1980s, Yugoslavia had become “a de-facto confederation of six independent economies with loose mutual economic ties pursuing their own interests at the federal expense.”

Tito had managed this fragmentation through personal authority and party discipline; his successors lacked both resources.

Economic Contradictions and the Failure of Self-Management

The Ideological Vision and Practical Distortion

Tito’s signature economic innovation—workers’ self-management (samoupravljanje)—represented an attempt to navigate between Soviet command planning and capitalist market systems.

Introduced in the 1950s and codified in successive reforms (particularly the decisive 1965 liberalisation), self-management theoretically transferred productive decisions from state bureaucrats to workers’ councils, which would democratically determine wages, investment levels, and production priorities.

This model was heralded internationally as a “third way” between Soviet totalitarianism and Western capitalism, attracting genuine interest from progressive economists and social democratic theorists. In principle, it offered dignity and agency to workers previously treated as interchangeable labour units.

In practice, self-management generated pathological incentive structures that undermined long-term economic sustainability. Work councils composed of employed workers—not the broader working class—made decisions about income distribution.

These councils faced structural incentives to maximise current wages for existing workers rather than invest in future capacity or accommodate new entrants.

The wage ratio between the highest and lowest paid workers expanded from 1:3.5 in the early planned economy to 1:20 by 1967, indicating that wage inequality actually increased under worker self-management. This contradicted socialist ideology while failing to generate efficiency gains comparable to market competition.

Labour Market Distortions and Emigration

The practical consequence was labour market dysfunction. Workers’ councils restricted new hiring to preserve wage levels for incumbent members, creating persistent unemployment and incentivising emigration.

Yugoslavia opened its borders to labour emigration in 1966 specifically to address unemployment created by this mechanism.

The response was dramatic: by 1981, approximately 10 percent of Yugoslavia’s workforce had emigrated to Western Europe, primarily West Germany, draining the domestic labour supply of productive workers precisely when growth began to decelerate.

Foreign worker remittances constituted 50 percent of export earnings in 1973, indicating profound dependence on external transfers rather than domestic production.

Unemployment became a chronic structural feature of Tito’s Yugoslavia in ways unknown in Western capitalist economies at the time. Even during the “golden seventies,” unemployment rates exceeded 13.8 percent in 1980, and reached 17 percent in the 1980s with an additional 20 percent underemployed.

Youth unemployment was particularly acute: 60 percent of the unemployed were under age 25, suggesting that the system failed to integrate successive generations into productive activity.

The Gini Coefficient and Rising Inequality

Despite socialist ideology emphasising equality and workers’ control, Yugoslavia’s wealth inequality (measured by the Gini coefficient) reached 0.32–0.35, substantially higher than the Soviet Union’s 0.275 despite the USSR’s longer existence as a socialist state.

Regional inequality also persisted throughout Tito’s rule, with developed republics (Slovenia and Croatia) vastly outpacing economically dependent regions (Macedonia, Kosovo, Montenegro).

Federal investment policies attempted to narrow these gaps through resource transfers, yet the structural differences—in infrastructure, education, industrial capacity, and capital availability—proved resistant to correction.

Market Reforms and the Debt Trap

Recognising stagnation, Yugoslav policymakers initiated radical market-oriented reforms in 1965, joining the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1966 and liberalising prices, foreign trade, and enterprise autonomy.

Banks replaced the central investment fund as the primary allocator of capital, theoretically creating market discipline. Instead, banks subsidised capital and maintained “soft budget constraints”—assured credit access for even poorly performing firms.

The reforms stimulated trade expansion with OECD countries and initially boosted growth, but by the 1980s had created unsustainable debt obligations without generating corresponding productivity improvements.

The 1983 debt crisis forced Yugoslavia to turn to the International Monetary Fund for assistance, but IMF conditionality demanded precisely the kind of shock therapy and economic restructuring that destabilised the political consensus holding the federation together.

IMF-mandated austerity measures reduced real wages by approximately 30 percent, triggering unprecedented labour unrest. Strike frequency surged from 30 strikes in 1978 to 696 in 1985, indicating profound working-class discontent.

The worker self-management system, supposed to prevent such alienation, proved powerless against external debt obligations and IMF discipline.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: The Path from Stability to Dissolution

The Paradox of Decentralisation Without Integration

Tito’s solution to managing Yugoslavia’s ethnic diversity involved decentralising political and economic authority to republics while maintaining party discipline and security apparatus control.

This arrangement preserved stability during his lifetime because personal authority and party hierarchy could override republican parochialism. However, each constitutional reform (1953, 1963, 1974) further diffused federal authority, steadily shifting power from Belgrade to republican centres.

The 1974 Constitution—adopted while Tito lived—proved particularly consequential. It formalised the system of rotating collective presidency and institutionalised “symmetrical federalism” designed to prevent any single republic (particularly Serbia) from dominating others.

The unintended consequence was federal paralysis. Decision-making required consensus among representatives of republics with divergent interests; federal institutions could not enforce discipline or override republican obstruction. When economic crisis emerged in the 1980s—requiring coordinated policy responses across the federation—the system proved incapable of decisive action.

Meanwhile, decentralisation had allowed each republic to develop separate economic policies, media infrastructure, and security apparatus, progressively eroding the integrative function that communist party hierarchy once provided.

Economic Crisis as Catalyst for Political Disintegration

The oil shocks of the 1970s and 1980s exposed Yugoslavia’s structural vulnerability: its growth model depended on expanding foreign credit, and sustained oil price increases rendered external financing increasingly difficult. Rather than coordinated federal response, the crisis manifested as regional competition for scarce federal resources.

Wealthier republics (Slovenia and Croatia) resented subsidising poorer regions; poorer regions demanded continued redistribution. Economic scarcity transformed distributional politics into existential struggle.

The 1979 oil shock triggered immediate macroeconomic deterioration. Industrial capacity utilisation fell; investment collapsed; unemployment surged. Inflation, initially suppressed through price controls, eventually exploded: triple-digit inflation in 1987–1988 gave way to four-digit hyperinflation in 1989.

These conditions destroyed the material basis for the implicit social contract: citizens had tolerated limited political freedom in exchange for full employment, subsidised services, and material security. As these material guarantees dissolved, the legitimacy of communist party rule evaporated.

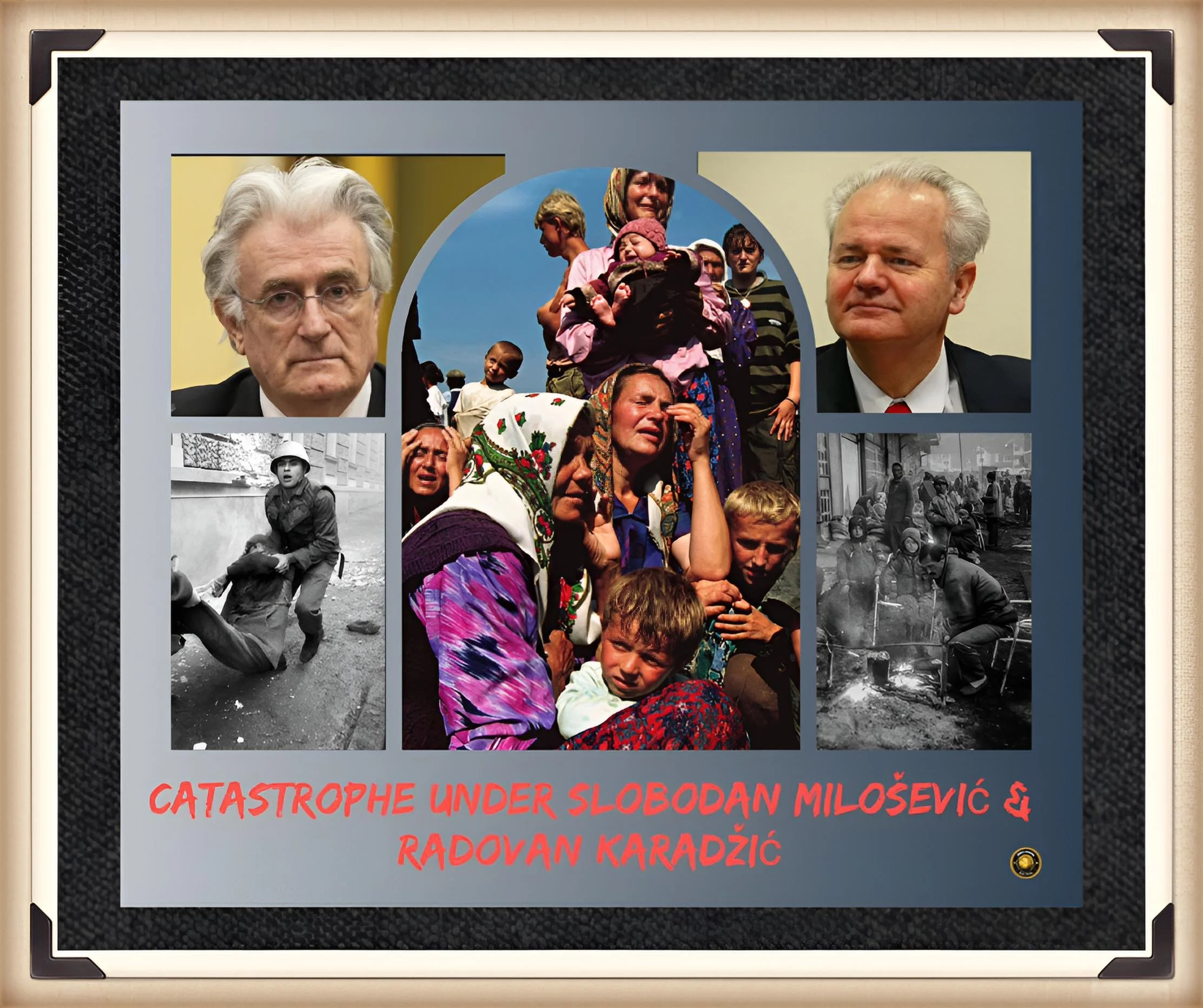

The Succession Crisis and Ethnic Mobilisation

Tito’s death on 4 May 1980 removed the centralising authority that had held the federation together through sheer force of personality and the legitimacy derived from partisan victory and anti-Soviet defiance.

His successors—the rotating collective presidency—lacked both personal authority and institutional capacity to manage competing republican interests. The system he created for orderly succession proved incapable of providing effective governance during crisis.

Into this vacuum stepped nationalist politicians who recognised that economic distress and political uncertainty created opportunities for ethnic mobilisation.

In Serbia, Slobodan Milošević rose to prominence by championing Serbian interests against perceived discrimination—particularly regarding Kosovo’s autonomous status and the perceived overrepresentation of Serbs in the security apparatus.

In Croatia and Slovenia, nationalist movements emerged demanding greater autonomy or outright independence. The League of Communists, which had provided ideological unity and institutional discipline, fragmented along republican lines.

At the January 1990 party congress, the Serbian delegation blocked all reform proposals from Croatian and Slovene representatives, prompting their walkout and effectively ending the “brotherhood and unity” that communist party hierarchy had enforced for four decades.

International Context and the Erosion of Yugoslavia’s Strategic Importance

During the Cold War, Yugoslavia maintained geopolitical significance as the non-aligned leader and a counterweight between superpowers.

Tito’s successful defiance of Stalin made him an important symbol of independence; his leadership of the Non-Aligned Movement (founded 1961) gave Yugoslavia diplomatic influence disproportionate to its size.

This international positioning provided both practical benefits (Western economic and military support) and ideological legitimacy (Yugoslavia as a progressive alternative to both communist bloc and capitalist West).

The Cold War’s end destroyed this strategic rationale. Yugoslavia no longer represented the valuable “third way”; instead, it appeared as an anachronistic socialist federation incompatible with the emerging liberal democratic and market-oriented Europe.

The European Union, in recognising Slovene and Croatian independence in 1991 while refusing to renegotiate republican borders, inadvertently transformed territorial disputes into matters of state survival.

Once Slovenian and Croatian independence became matters of international recognition rather than internal negotiation, the struggle for territory and minority rights became existential for all parties.

The prospect of Serbian minorities becoming foreign nationals in newly independent states, or Croatian minorities similarly displaced, created incentives for territorial conquest that transformed political competition into warfare.

The Contours of Authoritarian Rule

While Tito’s Yugoslavia permitted freedoms—in art, literature, film, and intellectual inquiry—that were unthinkable in the Soviet bloc, it remained fundamentally authoritarian. The Communist Party retained monopoly over political organisation; competing political parties were forbidden; opposition to party authority was suppressed through secret police apparatus and prisons.

Post-World War II Yugoslavia witnessed extensive arrests of suspected “war criminals” and “anti-communist” elements, systematic elimination of potential rival power bases (including removal of intellectuals, religious leaders, and military figures who might command autonomous loyalty), and the creation of a culture of fear.

The “Croatian Spring” demonstrated the regime’s intolerance for dissent even when emerging from within communist party structures. Reformers seeking greater autonomy and economic justice were removed from power and their movement suppressed.

This pattern recurred: whenever popular movements or institutional actors challenged party authority or federal unity, they were forcefully repressed. The regime’s self-understanding as engaged in permanent struggle against “enemies of the state” justified continuous surveillance and coercive control.

Yet Tito’s authoritarianism differed in degree (though not fundamental kind) from Stalin’s Soviet Union. Labour camps existed but were not universal instruments of terror; executions of political prisoners were far less frequent; cultural life permitted substantially greater pluralism.

Scholars debate whether Tito’s Yugoslavia should be classified as “totalitarian” in the strict sense, with some arguing that the regime’s decentralisation and permitted cultural freedoms disqualify it from that designation. What seems clear is that it represented an authoritarian system with certain liberal features—a characterisation applicable to various post-colonial and Cold War-era states, but distinct from both democratic governance and pure totalitarian control.

Facts and Concerns: The Balance Sheet

Genuine Achievements

The factual record demonstrates clear accomplishments: rapid industrialisation exceeding global standards; literacy and educational expansion that erased one of Europe’s most severe knowledge gaps; healthcare advancement and improved mortality statistics; international influence and diplomatic achievement disproportionate to national size; resistance to Soviet domination establishing a model of “national communism” that inspired independence movements elsewhere; and genuine worker participation in enterprise management that, despite its pathologies, offered more agency than Soviet command systems provided.

Persistent Failures

Equally undeniable: structural unemployment that persisted even during growth periods; wealth inequality that rose rather than fell under worker self-management; regional disparities that federal policies failed to eliminate; ethnic tensions that suppression rather than integration merely postponed; institutional dependence on personalised authority that became catastrophic weakness upon succession; debt accumulation that created unsustainable external obligations; and authoritarian political control that prevented democratic resolution of competing interests.

The Sustainability Question

The critical evaluation must address sustainability: a political system cannot be judged successful if it collapses immediately upon the departure of its founding leader.

Tito’s regime functioned as long as Tito lived, but it lacked institutional resilience or political legitimacy independent of his person.

The successor mechanism he designed—rotating collective presidency—proved wholly inadequate to managing competing republics during economic crisis. This suggests fundamental institutional failure regardless of the achievements of earlier decades.

Implications and Future Pathways

The Counterfactual: What If Tito Had Democratised?

One might ask whether Tito could have managed Yugoslavia’s transition to democracy in ways that preserved unity. Historical evidence suggests severe constraints.

The underlying ethnic tensions were genuine and deep; suppression rather than resolution left them unaddressed. Regional economic disparities created objective conflicts of interest (wealthier republics resented subsidising poorer ones).

By the time economic crisis emerged in the 1980s, the international environment had shifted dramatically—the Cold War’s end eliminated Yugoslavia’s strategic importance precisely when domestic legitimacy was collapsing.

Democratic transition under Tito’s leadership might have prevented some of the subsequent violence, particularly if constitutional negotiations established mechanisms for ethnic minority protection and power-sharing (as emerged in post-1990s arrangements, though tardily).

However, fundamental contradictions—competing claims to territory, economic resources, and political authority—likely would have persisted. Whether democratic institutions could have accommodated these tensions without violent fragmentation remains an open historical question.

Alternative Development Paths

Some scholars argue that Yugoslavia’s experience illuminates the limitations of “market socialism” as a development model.

The distorted labour incentives created by worker self-management—where incumbent workers maximised their own wages rather than investing in future capacity or employment growth—suggest structural flaws in the concept itself.

From this perspective, Yugoslavia might have achieved greater long-term stability through either orthodox Soviet-style planning (concentrating investment decisions in state apparatus) or genuine market liberalisation (permitting capital mobility and labour displacement).

The hybrid system combined disadvantages of both while capturing advantages of neither.

Conclusion

Josip Broz Tito was neither simply a “good” nor a “bad” leader; he was a historically consequential figure who achieved remarkable modernisation within a brutally short timeframe while simultaneously establishing structural vulnerabilities that guaranteed eventual catastrophe.

His rule produced genuine improvements in literacy, healthcare, industrialization, and living standards that objectively enhanced human welfare for millions of Yugoslavs. His defiance of Stalin demonstrated that communist regimes could escape Soviet dominance and chart independent paths. His success in managing a multinational state through a combination of federalisation and party discipline represented a genuine achievement in comparative political terms.

Yet stability under Tito rested on foundations so fragile that the system collapsed within a decade of his death. The ethnic tensions he suppressed but did not resolve; the economic model that generated growth through debt rather than productivity; the political system that depended entirely on his personalised authority; the institutional arrangements that prevented coordinated response to crisis—these represented not peripheral failures but fundamental structural defects.

The most historically accurate assessment may be that Tito was a successful autocrat whose personal effectiveness as a leader was unmatched by the durability of the institutions he created.

He transformed Yugoslavia from a war-devastated, largely peasant society into an industrial state with advanced education and social services. He gave Yugoslavs a voice in global affairs disproportionate to their numbers. He held together a multinational federation that might otherwise have fragmented earlier. These were genuine accomplishments of significant historical magnitude.

However, his concentration of power in personal authority rather than institutional structures; his suppression rather than resolution of ethnic tensions; his tolerance of economic models that generated employment dysfunction and unsustainable debt; and his failure to establish succession mechanisms capable of surviving his death—these represented failures of equal historical significance.

The subsequent Yugoslav Wars, which killed approximately 140,000 people and displaced millions, emerged directly from the unresolved tensions and institutional vacuums that Tito’s regime created.

Tito was a good leader in the sense of achieving measurable material improvements and resisting external domination.

He was a poor leader in the sense of creating durable institutions or resolving the fundamental contradictions of Yugoslavia’s existence.

His legacy endures not in stable successors or peaceful resolution of conflicts, but in the catastrophic violence that followed his death—a verdict on the unsustainability of personalised authority and suppressed conflict rather than on the merits of his achievements.