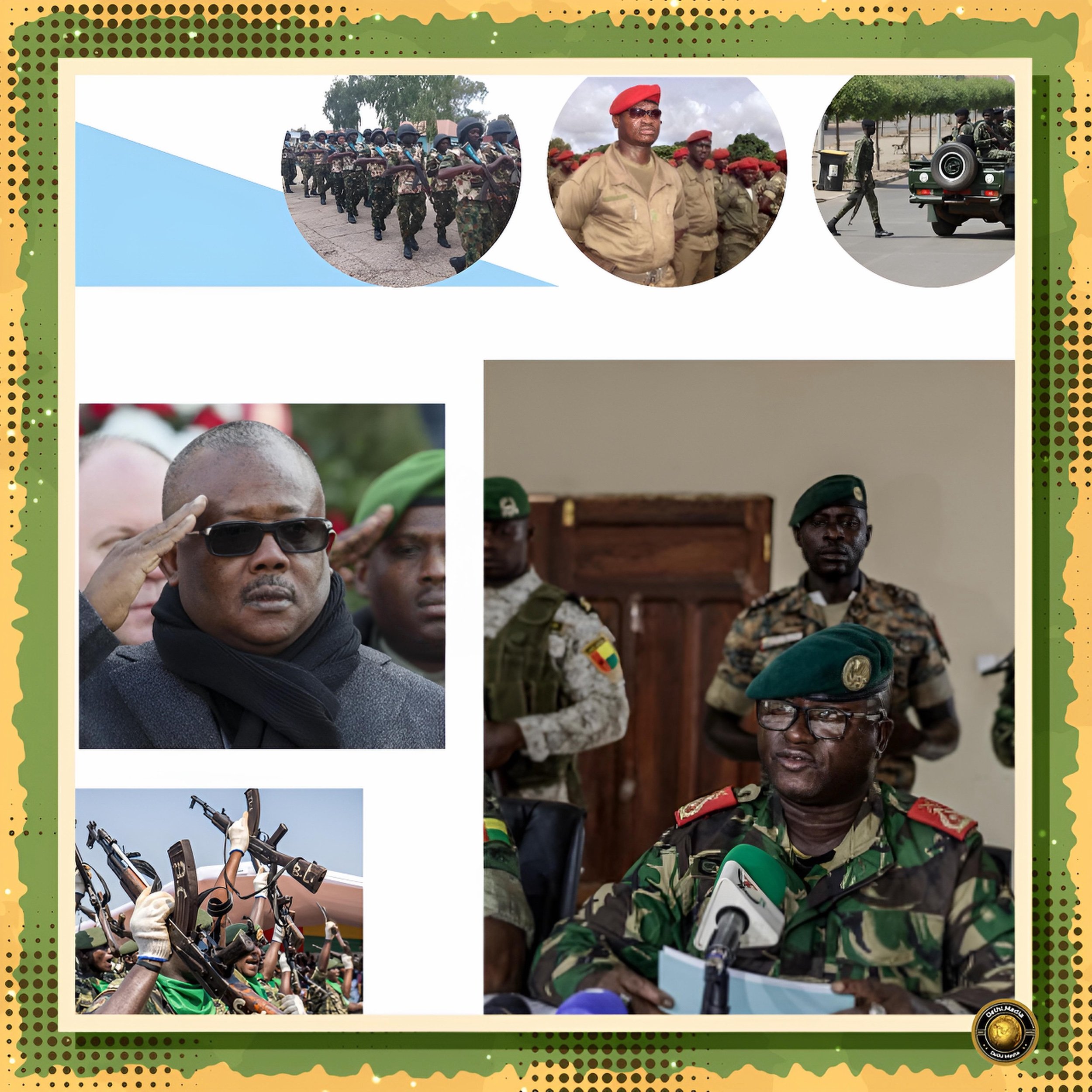

The November 2025 Guinea-Bissau Military Coup: Constitutional Collapse and the Perpetuation of Institutional Dysfunction

Introduction

Executive Summary

On November 26, 2025, Guinea-Bissau underwent its most consequential military intervention in a quarter-century, with armed forces establishing “The High Military Command for the Restoration of Order” and assuming sovereign authority over the West African nation.

This coup d’état transpired under extraordinary circumstances: merely seventy-two hours following presidential and legislative elections, and precisely one day before the National Electoral Commission was scheduled to announce provisional results.

The military’s seizure of power materialized amid intensifying allegations that President Umaro Sissoco Embaló—arrested without resistance at 13:00 GMT at his office in the presidential palace—had orchestrated systematic institutional deterioration, culminating in the unprecedented juridical exclusion of the PAIGC (Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde), the venerable nationalist party that spearheaded Guinea-Bissau’s decolonization struggle.

This coup simultaneously represents a continuation of Guinea-Bissau’s endemic pattern of military interventionism while constituting a manifestation of the broader West African phenomenon of military reassertion following the comparative institutional stability of the preceding two decades.

Introduction

The Immediate Crisis: Contextualizing the Military Intervention

Chronology and Operational Parameters

The military intervention commenced with sustained firearms discharge in the vicinity of three critical governmental loci:

(1) the presidential palace

(2) the National Electoral Commission headquarters

(3) the Ministry of Interior.

These simultaneous demonstrations of coercive capability—occurring approximately one hour before 14:00 GMT—constituted unmistakable signals of coordinated institutional capture rather than spontaneous insurrectionary activity.

President Embaló reported his apprehension to the French media outlet Jeune Afrique, characterizing his detention as nonviolent whilst simultaneously designating the Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces as the orchestrator of the coup.

Alongside Embaló’s detention, military authorities apprehended

(1) General Biaguê Na Ntan (Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces)

(2) General Mamadou Touré (Deputy Chief of Staff

(3) Interior Minister Botché Candé

This constituted a decapitation of the leadership of the executive and security apparatus.

The military subsequently established provisional governance structures through the establishment of “The High Military Command for the Restoration of Order,” announcing their commitment to maintaining order “until further notice” whilst systematically implementing comprehensive border closures and a nocturnal curfew regime.

The Electoral Dispute’s Proximate Catalysts

The coup materialized within an extraordinarily contentious electoral context.

Both incumbent President Embaló and opposition candidate Fernando Dias da Costa—the 47-year-old leader of the Party for Social Renewal (PRS) and erstwhile vice-president of the National People’s Assembly—pronounced themselves victors within forty-eight hours of the November 23 elections, notwithstanding the explicitly stated prohibition by the electoral commission against premature results announcements.

Embaló's campaign asserted achieving approximately 65% of the aggregate votes, whilst Dias’s coalition maintained they had surpassed the 50% threshold required to preclude a runoff election.

This electoral bifurcation acquired its particular acuity from the historically unprecedented juridical disqualification of the PAIGC—Africa’s oldest extant nationalist organization and the organization that led Guinea-Bissau’s anti-colonial armed struggle.

In October 2025, Guinea-Bissau’s Supreme Court rendered a determination disqualifying both the PAIGC-led coalition (the Inclusive Alliance Platform – Terra Ranka) and its presidential aspirant Domingos Simões Pereira, the former Prime Minister and parliamentary presiding officer, on purportedly procedural grounds relating to document submission timing.

The Supreme Court’s adjudication remained substantially opaque regarding its jurisprudential reasoning, thereby generating widespread suspicion among civil society actors, international election observation missions, and opposition interlocutors that the exclusion represented judicially mediated political engineering rather than impartial adjudication.

The PAIGC’s exclusion fundamentally restructured the electoral competitive landscape.

Confronted with unprecedented organizational incapacity to participate, the PAIGC leadership subsequently conferred its organizational endorsement upon Fernando Dias, thereby transforming the previously peripheral candidate into Embaló’s principal adversary.

This strategic realignment precipitated substantial uncertainty regarding electoral outcomes—a circumstance conspicuously anomalous within the Embaló presidency’s preceding five-year tenure, during which institutional mechanisms and coercive apparatus had functioned to consolidate executive predominance.

Historical Trajectory: Guinea-Bissau’s Protracted Pattern of Military Interventionism

Guinea-Bissau’s incorporation into the international system following Portuguese decolonization in 1974 has been characterized by what comparative analysts term “coup-proneness”—a designation originating from the nation’s experience of four successful military seizures of power and numerous failed insurrectionary plots across a fifty-one-year independence trajectory.

This historical recursivity merits systematic examination, as contemporary developments represent not an aberration but the perpetuation of deeply embedded institutional dysfunction.

The Early Independence Period and Vieira’s Three-Decade Hegemony (1974-1999)

Following the termination of Portuguese colonial governance, Luis Cabral—half-sibling of the assassinated anti-colonial theorist Amílcar Cabral—assumed the presidency.

This initial post-independence configuration persisted until November 14, 1980, when Prime Minister João Bernardo Vieira orchestrated a bloodless coup, subsequently establishing a “Revolutionary Council” that exercised comprehensive executive and legislative prerogatives.

The 1980 intervention initiated what would constitute three decades of Vieira’s predominance over Guinea-Bissau’s political economy, interrupted only by electoral cycles that themselves frequently validated his continued tenure.

Vieira’s extended regime encountered its most consequential challenge commencing in June 1998, when Brigadier-General Ansumane Mané—subsequently designated by official authorities as the perpetrator of an insurrectionary conspiracy—precipitated a civil conflict that persisted until May 1999.

This eighteen-month conflagration resulted in hundreds or potentially thousands of deaths. It precipitated the displacement of approximately three hundred thousand individuals, representing roughly fifteen percent of Guinea-Bissau’s extant population.

Mané’s putative coup attempt ostensibly originated in disciplinary grievances within the military hierarchy.

However, scholarly retrospection suggests that more complex institutional antagonisms over military autonomy, resource allocation, and civil-military relations animated the conflict.

The civil conflict ultimately culminated in Vieira’s deposition. However, his subsequent reincorporation into Guinea-Bissau’s political elite via electoral victory in 2005 and assassination in March 2009 exemplifies the nation’s turbulent elite circulation patterns.

Post-Conflict Instability and Institutional Fragmentation (2000-2012)

Following Vieira’s initial removal, free and competitive elections in 2000 brought Kumba Yala to the presidential office.

Kumba Yala’s governance, characterized by scholarly assessment as simultaneously erratic and increasingly autocratic, precipitated military dissatisfaction within three years.

In September 2003, military authorities—operating through General Veríssimo Correia Seabra, who declared himself interim president—orchestrated Yala’s removal, thereby inaugurating yet another iteration of military guardianship over state institutions.

Vieira’s subsequent electoral triumph in 2005 created ephemeral expectations of renewed stability.

However, March 2, 2009, witnessed the assassination of both Vieira and Chief of Staff General Tagme Na Waié in an explosion at the Armed Forces headquarters, precipitating acute institutional disorientation and renewed succession competition.

These personnel removals—fundamentally destabilizing the security apparatus hierarchy—generated conditions conducive to further institutional fragmentation through the remainder of the 2009-2012 quinquennium.

The pattern of institutional volatility culminated in a military intervention on April 12, 2012, during which armed forces detained interim President Malam Bacai Sanha (who had assumed office following his electoral victory in 2009 and subsequent parliamentary succession) alongside former Prime Minister Carlos Gomes Júnior, concurrently disqualifying the frontrunner presidential aspirant precisely two weeks preceding a scheduled second-round runoff election.

This 2012 coup demonstrated the military's capacity to intervene at critical junctures of competitive electoral processes, establishing a pattern that would become recurrent: pre-results military seizure of authority.

Comparative Stabilization and Elite Professionalization (2014-2019)

In contrast to the tumultuous preceding decades, the 2014-2019 electoral cycle witnessed José Mário Vaz’s emergence as the first president since independence to complete a full constitutional mandate.

Yet institutional fragilities persisted beneath superficial normalcy: Vaz’s tenure encompassed persistent executive-legislative antagonism, deteriorating institutional capacity regarding counternarcotics enforcement, and endemic state capture by transnational narcotics trafficking networks.

The 2019 presidential election between incumbent Vaz and opposition challenger Domingos Simões Pereira sparked months of post-election dispute.

Embaló’s emergence as the victor following four months of opaque Supreme Court proceedings and ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) mediation signaled not democratic consolidation but rather institutional capture by competing elite factions utilizing formal juridical mechanisms to obfuscate substantively contestable electoral determinations.

Embaló’s Presidency: From Contested Legitimacy to Authoritarian Personalization (2020-2025)

Initial Constitutional Ambiguities and Executive Consolidation

Embaló’s February 2020 assumption of the presidency occurred amid persistent allegations that his electoral victory lacked substantive legitimacy.

His initial governance trajectory demonstrated systematic efforts to consolidate executive authority by incrementally circumscribing competing power centers.

The president’s May 2022 parliamentary dissolution—justified through allegations of corruption and institutional incompetence—initiated the first of multiple episodes of constitutional suspension that would characterize his tenure.

The December 2023 constitutional crisis represented the apotheosis of Embaló’s institutional aggrandizement.

Following clashes between military units that he attributed to coup conspirators, Embaló dissolved parliament a second time and subsequently appointed a “presidential initiative government” that operated without parliamentary authorization or oversight.

This extra-constitutional arrangement persisted throughout the subsequent months, with the dissolved parliament unable to reconvene, thereby leaving vacant critical constitutional positions, including electoral commission membership and Constitutional Court directorships whose statutory tenures had terminated.

Juridical Mechanisms and Opposition Elimination

Embaló’s administration simultaneously orchestrated the elimination of organized opposition through mechanisms ostensibly grounded in juridical procedure.

The October 2025 Supreme Court disqualification of the PAIGC and its presidential candidate Domingos Simões Pereira—justified through allegations of procedural noncompliance regarding document submission deadlines—constituted the first instance in Guinea-Bissau’s post-independence history wherein the nation’s dominant nationalist organization faced institutional exclusion from electoral competition.

Civil society organizations, international observation missions, and opposition intellectuals characterized this determination as juridically illegitimate and substantively oriented toward electoral manipulation.

Deteriorating Democratic Civic Space

Concurrent with executive aggrandizement, Embaló’s administration presided over qualitative deterioration in democratic civic freedoms.

Human rights documentation from international and indigenous NGOs recorded systematic patterns of opposition harassment, journalistic intimidation, constraints upon civil society organizational autonomy, and security force disruption of opposition political congresses.

The 2021 invasion of the military bar association headquarters and subsequent episodes of activist and journalist harassment exemplified the normalization of state coercive capacity deployment against political opponents.

Structural Factors Illuminating the November 2025 Intervention

Constitutional Defects and Institutional Ambiguities

Guinea-Bissau’s semi-presidential constitutional architecture—promulgated in its contemporary iteration in 1984 and substantially amended in 1996—incorporates provisions that historically generate executive-legislative friction and systematize ambiguity regarding authority distribution.

The constitution’s delineation of presidential and parliamentary prerogatives remains substantially underdetermined regarding crisis management, thereby establishing the military as a potential institutional arbiter of elite disputes.

This constitutional indeterminacy acquired particular salience through the systematic institutional depletion occasioned by parliamentary dissolution.

With the National People’s Assembly incapacitated since December 2023, constitutional vacancies have accumulated regarding the composition of the electoral commission and the leadership of the Constitutional Court.

These governance lacunae delegitimized the electoral apparatus, rendering the November 23 elections organizationally deficient and institutionally questionable.

Political Polarization and the PAIGC Paradox

The PAIGC’s juridical exclusion precipitated the fragmentation of elite consensus.

The PAIGC has constituted Guinea-Bissau’s sole repository of revolutionary nationalist legitimacy—the organization responsible for conducting the armed decolonization struggle and exemplifying organizational continuity throughout the independence epoch.

Its disqualification fractured the historically operative understanding that fundamental political legitimacy derived from a nationalist historical narrative.

Simultaneously, the PAIGC’s organizational incapacity generated unexpected political fluidity.

Domingos Simões Pereira’s strategic endorsement of Fernando Dias transformed electoral competition from a predetermined encounter between Embaló and a fragmented opposition into a substantively contested electoral process.

This unanticipated competitive uncertainty—absent throughout Embaló’s preceding tenure—appears to have generated military anxiety regarding outcome unpredictability and prospective political realignment.

The Narcotics Dimension and Parallel Power Structures

Guinea-Bissau’s emergence as a critical transshipment node within the Latin American cocaine-to-Europe trafficking apparatus constitutes a structural factor substantially underexamined within mainstream Western analysis but omnipresent within regional security assessments.

Since the early 2000s, Guinea-Bissau has accumulated the designation “Africa’s first narco-state,” reflecting the penetration of narcotics trafficking networks throughout governmental institutions, military factions, and security apparatus formations.

This criminal economy operates through parallel institutional structures that frequently supersede formal governmental authority regarding resource allocation and decision-making.

Military factions maintain differential relationships with narcotics trafficking networks, thereby creating incentive structures that diverge from purely political considerations.

The military’s November 26 intervention may reflect not merely electoral disputes but also antagonisms between military factions over the governance of narcotics trafficking operations and the distribution of resources derived therefrom.

Regional Military Demonstration Effects and Sahel Contagion

Guinea-Bissau’s position within West Africa’s broader pattern of military interventionism warrants analytical attention.

The 2020-2025 quinquennium witnessed successful military coups in

(1) Mali (August 2020)

(2) Burkina Faso (January 2022 and September 2022)

(3) Niger (July 2023)

(4) Sudan (October 2021)

(5) Chad (April 2021)

(6) Guinea (September 2021)

(7) Gabon (August 2023).

Within this regional context of military assertiveness, Guinea-Bissau’s November 2025 coup represents not an anomaly but a manifestation of broader geopolitical dynamics.

Scholarly analysis of the West African coup wave emphasizes “demonstration effects” and organizational learning among military stakeholders.

Coup leaders observe operational strategies, consolidation methodologies, and international response patterns from proximate predecessors, thereby generating behavioral convergence.

The relative international forbearance toward previous coups—characterized by limited sanctions, inconsistent regional enforcement mechanisms, and the ultimate international normalization of military governance—has presumably attenuated the perceived costs of the army's seizure of authority.

The Military’s Articulated Justifications and Unarticulated Motivations

Military spokesperson Dinis N’Tchama, presenting the military command’s statement on state television within formal military attire, articulated the coup’s purported rationale as prevention of “an ongoing scheme to destabilize our nation.”

The military’s statement attributed this alleged destabilization initiative to “a coordinated plan devised by certain national politicians in collaboration with well-known local and international drug traffickers, along with attempts to manipulate the electoral outcomes.”

These formulations remain substantially opaque regarding specific allegations or substantive evidence.

The military’s reference to electoral manipulation creates analytical ambiguity about whether it opposed an anticipated Embaló victory it deemed illegitimate or feared a Dias victory it considered existentially threatening to its institutional interests.

The invocation of narcotics trafficking networks alongside electoral manipulation suggests military concern regarding governance of the criminal economy rather than purely democratic governance principles.

Structural Implications and Prospective Trajectories

The November 2025 Guinea-Bissau coup crystallizes multiple overlapping processes of institutional decay, elite antagonism, and security force fragmentation.

The military’s assumption of authority necessarily interrupts the provisional electoral process and suspends constitutional democracy, thereby introducing profound uncertainty regarding Guinea-Bissau’s near-term political trajectory.

Potential future developments remain substantially indeterminate.

The military may pursue a transition toward competitive electoral processes within modified constitutional parameters, establish sustained junta governance, or broker negotiated settlements that incorporate selective elite participation.

ECOWAS response patterns, international diplomatic engagement, and the sustainability of military organizational cohesion will substantially determine the coup’s ultimate institutional consequences.

Conclusion

Guinea-Bissau and the Perpetuation of Democratic Fragility

The November 26, 2025, military coup in Guinea-Bissau represents the concatenation of multiple structural vulnerabilities

(1) constitutional ambiguities establishing military arbitration capacities, elite antagonism following institutional exclusion mechanisms

(2) personalistic executive aggrandizement eroding institutional checks

(3) integration within criminal economy networks generating divided military allegiances

(4) regional demonstration effects emphasizing military intervention viability.

While proximate causation derives from contested electoral outcomes and anticipated result announcement, underlying structural factors encompassing five decades of institutional dysfunction necessarily contextualize this intervention as a manifestation rather than an aberration.

Embaló’s governance demonstrated a systematic erosion of democratic institutional foundations through parliamentary dissolution, the elimination of opposition, restrictions on civic space, and the aggrandizement of executive authority.

These actions, whilst ostensibly justified by security necessity and administrative efficacy imperatives, cumulatively delegitimized constitutional democracy within segments of the security apparatus and the political elite.

Simultaneously, the PAIGC’s unprecedented exclusion fractured elite consensus on the legitimacy of the electoral process and catalyzed political uncertainty absent during Embaló’s preceding tenure.

This circumstance—whether serendipitous or determinative—appears to have led to military decisions to preempt the announcement of results and assume direct authority.

Whether Guinea-Bissau’s military governance proves transitional or constitutes the inception of extended junta rule, the coup exemplifies the precarious institutional position of democracy within West Africa’s contemporary political economy.

The question confronting ECOWAS, international observers, and Guinea-Bissau’s civil society establishments remains not whether military intervention has occurred, but rather whether institutional mechanisms exist that are adequate to restore constitutional democracy under modified parameters that address underlying elite antagonism and security apparatus fragmentation.

The historical trajectory analyzed above provides limited grounds for optimism regarding the restoration of such institutions without substantive structural reform—a prospect that appears increasingly improbable in the foreseeable future.