Sudan ceasefire plan under fire ? Sudan Peace Plan Status and Current Conflict Situation

Introduction

Has the Peace Plan Been Rejected?

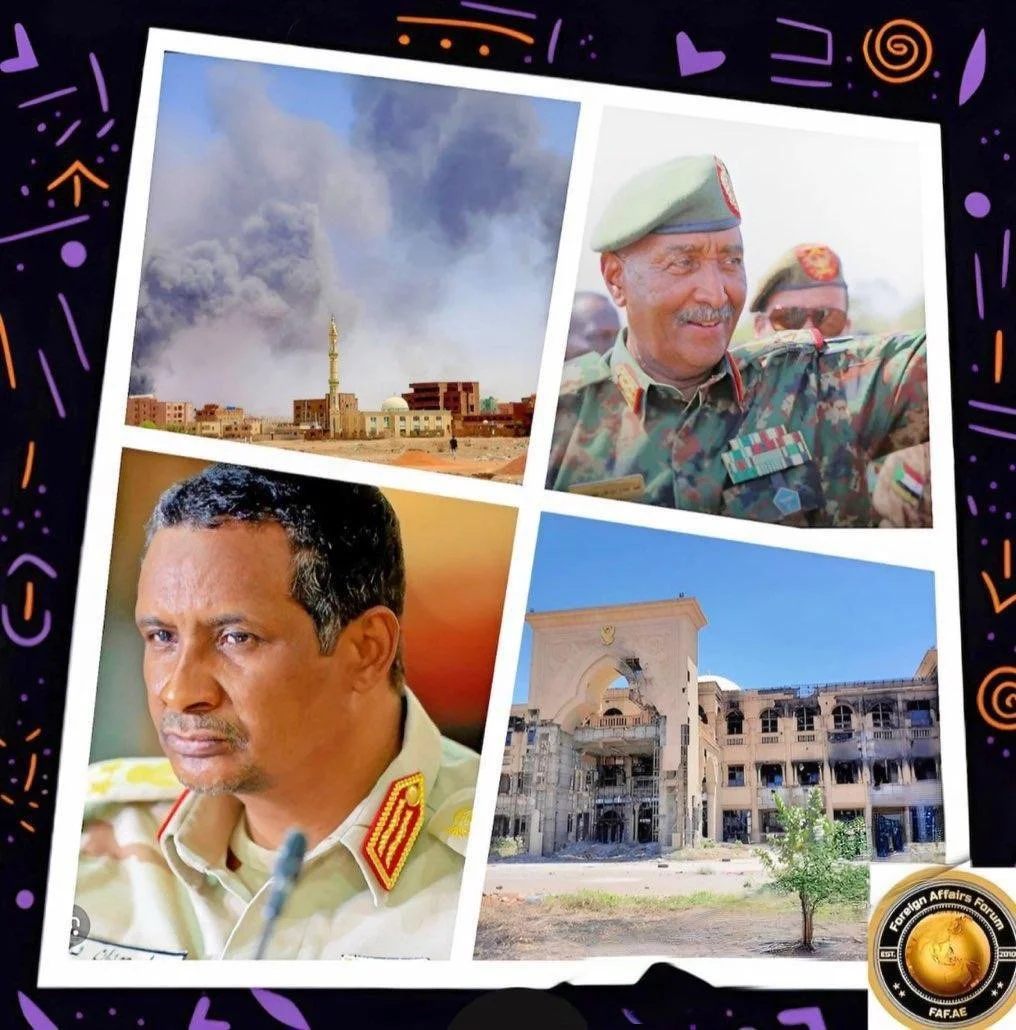

Both principal belligerents in Sudan’s civil war — the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) — have rejected or severely qualified their acceptance of the latest United States–led peace proposal.

The SAF under General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan unequivocally rejected the plan on 23–24 November 2025, describing it as “the worst document yet.”

Burhan condemned the mediators for partisan bias, arguing that the proposal effectively dismantles the Sudanese Armed Forces, dissolves state security agencies, and institutionalises the RSF as a permanent paramilitary actor.

He declared that any political process must begin only after the RSF withdraws from civilian areas and displaced persons are allowed to return to their homes.

Conversely, the RSF, commanded by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti), announced a unilateral three‑month humanitarian ceasefire on 24 November, ostensibly in response to mounting international condemnation of its atrocities in El‑Fasher.

Yet, the RSF has conspicuously refrained from endorsing the formal text of the ceasefire proposal as drafted by the international mediators.

As of 25 November 2025, neither faction has formally accepted the peace plan in its presented form.

The Quad Peace Plan: Framework and Principles

The US‑led Quad — comprising the United States, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates — unveiled a comprehensive roadmap on 12 September 2025. The plan unfolds in two sequential phases:

Phase I

An immediate three‑month humanitarian truce to facilitate aid delivery and ensure civilian mobility.

Phase II

A nine‑month political transition culminating in the establishment of a civilian‑led interim government.

The plan’s guiding doctrine stipulates that governance must not fall under the control of warring parties and that any transitional authority must be unequivocally civilian in orientation.

It further denounces extremist formations allegedly associated with the Muslim Brotherhood, implicitly targeting elements aligned with Burhan’s command.

Additionally, the roadmap demands cessation of all arms transfers to the belligerents, though it stops short of binding commitments by the Quad nations themselves.

Mediation Efforts and Diplomatic Dynamics

Massad Boulos, Washington’s Senior Adviser for Arab and African Affairs, spearheads the mediation process.

Operating mainly from Abu Dhabi, Boulos has employed shuttle diplomacy to bridge the chasm between the two sides, urging unconditional compliance with the ceasefire blueprint.

Collaborating closely with UAE presidential adviser Anwar Gargash, Boulos coordinates the Quad’s diplomatic strategy — with Saudi Arabia adopting an increasingly prominent role following Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s direct appeal to President Trump in mid‑November 2025.

However, the credibility and cohesion of this diplomatic undertaking remain under scrutiny. The contrasting allegiances of Quad members — with the UAE accused of arming the RSF while Saudi Arabia supports the SAF — undermine the appearance of a unified peace architecture.

Divergent Gulf Policies: UAE versus Saudi Arabia

The United Arab Emirates’ sustained backing of the RSF reflects a pragmatic, interest-based calculation rather than ideological alignment.

Through the RSF, the UAE seeks to project influence along the Red Sea corridor, secure access to Sudan’s gold and agricultural wealth, and safeguard trade and logistics nodes essential to its economic strategy.

The RSF functions as a pliant proxy capable of ensuring Emirati leverage within Sudan’s fragmented security order, outside the structures of an unreliably Islamist‑tinged state apparatus.

Saudi Arabia, by contrast, views the SAF as the legitimate custodian of state authority and a stabilising bulwark against the paramilitary disintegration of the Sudanese polity.

Riyadh’s resistance to the RSF stems from its aversion to militia autonomy, trafficking networks, and factional fluidity, all of which threaten Red Sea security and regional cohesion.

Consequently, Saudi Arabia has pressed Washington to impose sanctions — even secondary penalties against the UAE — to curtail RSF rearmament.

This schism between the two Gulf powers reflects their divergent philosophies of order:

Riyadh’s preference for conventional state institutions versus Abu Dhabi’s hybrid model of controlled fragmentation and proxy influence.

The Battlefield Reality and Humanitarian Collapse

On the ground, the military balance has tilted perilously towards the RSF. Following the fall of El‑Fasher on 26 October 2025, the RSF tightened its grip on western Sudan, liberating combat divisions for further advances towards Khartoum and Omdurman.

For the SAF, this loss represents an existential inflection point. Egypt has drawn a red line around Omdurman, apprehensive that the capital’s fall would destroy the last vestige of organised state authority.

The humanitarian toll is staggering: over 40,000 confirmed deaths (with independent estimates much higher), more than 14 million displaced, and widespread famine.

Reports of ethnic‑based massacres and systematic war crimes—particularly by the RSF in Darfur—have generated international revulsion and intensified calls for intervention.

Both factions, however, have repeatedly violated ceasefire agreements, reflecting the entrenched militarisation of the conflict and the absence of mutual trust.

Washington’s Re‑engagement and Strategic Crossroads

President Trump’s personal involvement following the Saudi appeal marked a new phase in US engagement.

His administration’s directives have prioritised Sudan’s peace process, though operationally most responsibilities remain in the hands of Boulos, whose experience in complex conflict mediation is limited.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio, meanwhile, is reportedly pursuing an assertive campaign to restrict RSF armament flows and potentially sanction the UAE — a move unprecedented vis‑à‑vis a longstanding Gulf ally.

This balancing act embodies the central paradox of US policy: the need to assert moral and strategic leadership in Sudan while preserving indispensable military basing rights on Emirati soil.

Conclusion

The Sudanese conflict now epitomises the broader structural failure of externally brokered peace frameworks that neglect the asymmetric incentives of the belligerents.

The SAF, perceiving the peace plan as a veiled attempt to dismantle its institutional power, remains obstinate; the RSF, believing itself on the cusp of outright victory, has no incentive to compromise.

The Quad’s diplomatic scaffolding, while conceptually robust, suffers from the internal contradictions of its sponsors — particularly the UAE–Saudi split, which converts mediation into an arena of proxy competition.

Unless a decisive external realignment occurs — either through Riyadh’s successful imposition of punitive sanctions on Abu Dhabi or a tangible RSF military setback — neither faction is likely to yield to international pressure.

The SAF’s leverage continues to erode, while the RSF’s territorial consolidation enhances its bargaining position, potentially entrenching a de facto partition of Sudan.

In the medium term, two possible trajectories emerge

RSF Ascendancy and De Facto Fragmentation:

If the RSF retains momentum, Sudan may evolve into a militarised fiefdom dominated by Hemedti’s forces, with regional warlordism replacing central authority.

This outcome would intensify humanitarian collapse and institutionalise a black‑market gold economy under Emirati patronage.

External Recalibration and Diplomatic Reset

Should US and Saudi pressure succeed in constraining Emirati support and enforcing a genuine arms embargo, the RSF’s logistical endurance could diminish, allowing for renewed negotiations under a revised peace framework.

Yet, the absence of credible enforcement mechanisms renders this scenario tenuous.

Realistically, peace in Sudan remains remote. The RSF’s atrocities and the SAF’s institutional rigidity have poisoned prospects for an inclusive political transition.

The most probable outcome is a prolonged, low‑intensity conflict punctuated by sporadic truces — a frozen war sustained by foreign interests and domestic despair.