U.S. Deterrence Against China’s Air Power: Strategic Analysis and Policy Recommendations

Executive summary

The U.S. military is no longer the only strong power in Asia. China has built advanced air defenses and missiles that make it harder for the U.S. to win a quick fight.

Instead of trying to beat China in a direct fight, the U.S. now wants to make any war with China very long and expensive. The goal is to make China think that attacking Taiwan or other countries would cost too much and not be worth it.

To do this, the U.S. is using:

Stealth drones and planes to spy and avoid Chinese defenses.

Electronic warfare to jam and confuse Chinese radar and missiles.

Many small drones and ships to attack from different places, making it hard for China to defend everywhere.

Stronger alliances with countries like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan to work together.

The best way for the U.S. to stop China from using its air power is not to try to win a quick battle, but to make any war slow, costly, and risky for China.

By working with allies, using new technology, and making China doubt its chances, the U.S. hopes to keep peace in Asia without having to fight a big war.

Introduction

The article’s core assertion—that U.S. military superiority can no longer be assumed against China in Asia and therefore requires a new strategic approach—proves particularly salient when examined through the lens of air defense suppression and counter-air power operations.

China’s layered, integrated air defense system (IADS), anchored by systems such as the HQ-9 family and supported by advanced radar networks and hypersonic missiles, presents a formidable challenge to traditional U.S. air operations.

The original premise that deterrence should emphasize cost imposition rather than denial becomes especially relevant when considering how the U.S. military can credibly threaten Chinese air power assets while operating within their defended airspace.

The Erosion of Air Superiority and the A2/AD Challenge

China’s anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) strategy fundamentally constrains how U.S. air forces can project power in the Indo-Pacific.

The U.S. Department of War assesses that adversaries are fielding counter-air weapons guided by space-based sensors with ranges exceeding 1,000 miles, creating unprecedented threats to traditional air operations that operated under the assumption of sanctuary beyond enemy air defense ranges.

China’s investment in long-range precision-strike systems, including intercontinental hypersonic vehicles and diverse air-, land-, and sea-launched missiles supported by advanced space-based targeting, poses acute risks to legacy platforms such as tanker aircraft that have historically operated with relative impunity.

The degradation of U.S. stealth advantages further complicates the operational calculus.

China’s latest radar simulations reveal that U.S. stealth fighters, including the F-22 and F-35, could be detected at 180 kilometers by land-based radars. In comparison, the F-35’s external weapons configuration compromises stealth and enables detection at 450 kilometers.

This technological convergence suggests that stealth alone no longer guarantees penetration of defended airspace, requiring a fundamental rethinking of how the U.S. military can effectively counter Chinese air defense systems.

Multi-Layered Counter-Air Defense Approach

Rather than optimizing U.S. military forces for clear-cut air superiority (a condition increasingly unattainable), Washington should pursue a multi-domain, integrated counter-air defense strategy combining military and nonmilitary elements.

The strategic framework should rest on three pillars: penetrating reconnaissance, electronic warfare suppression, and distributed attack capabilities.

Penetrating Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR)

The classified RQ-180 stealth reconnaissance drone represents a crucial emerging capability for countering Chinese air defense.

Designed for conducting penetrating ISR missions into defended airspace, the RQ-180, equipped with advanced stealth features that reduce radar cross-section, can conduct reconnaissance without risking manned assets.

It is equipped with an active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar and passive electronic surveillance measures.

This platform enables the U.S. military to map Chinese air defense networks, identify vulnerabilities, and provide targeting data for subsequent suppression operations—all while maintaining operational persistence in contested airspace.

The development of distributed ISR concepts emphasizes advanced computing to collect and prioritize critical data for near-real-time exploitation, moving away from legacy platforms deemed too vulnerable for modern contested warfare.

Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) Through Electronic Warfare

Recent combat experience demonstrates the critical vulnerability of advanced air defense systems to sophisticated electronic warfare (EW) tactics.

India’s successful strikes during Operation Sindoor in May 2025 exposed significant vulnerabilities in Pakistan’s Chinese HQ-9B air defense system—the same system Beijing promoted as a direct competitor to Russia’s S-400.

Pakistani air defenses failed to intercept any Indian missiles or drones, with Indian EW systems, particularly EL/M-2083 jammers, effectively blinding the HQ-9B’s HT-233 C-band radar.

The U.S. Air Force should accelerate deployment of advanced electronic warfare capabilities, particularly digital radio frequency memory (DRFM) jamming systems that can accurately replicate enemy radar signals and deceive air defense networks.

Ground-based special operations forces (SOF) equipped with DRFM jamming represent an asymmetric counter to China’s A2/AD architecture, enabling suppression of enemy radars from concealed positions with modular, transportable equipment.

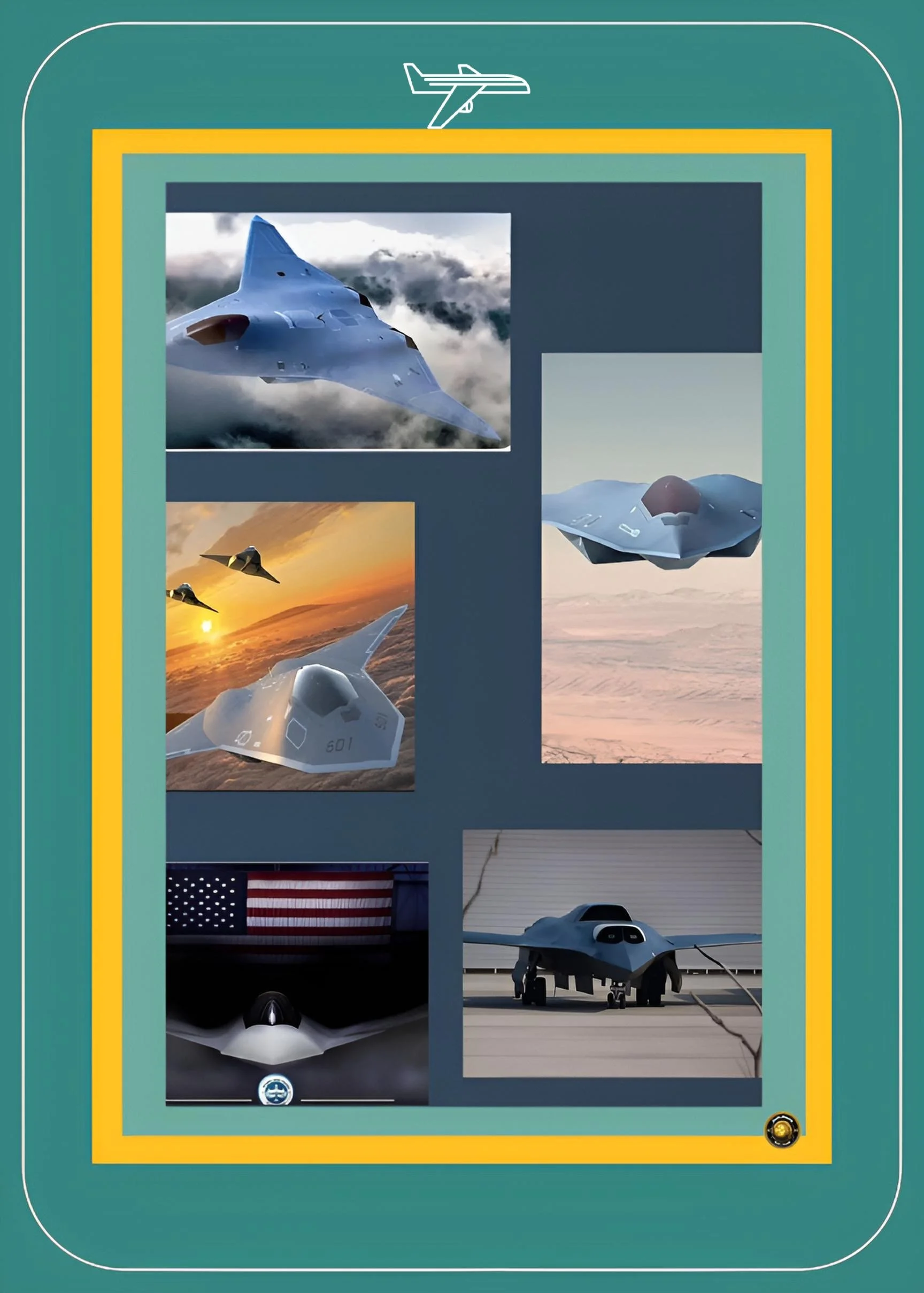

Next-Generation Stealth and Autonomous Platform Architectures

The Pentagon’s Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program addresses the inadequacies of current stealth capabilities.

The F-47 NGAD fighter is designed as a true “Stealth++” platform, combining Mach 2+ speed, 1,000-nautical-mile range, and advanced ceramic radar-absorbent coatings to achieve far lower observability than that of fifth-generation fighters.

Critically, the NGAD emphasizes a quarterback concept whereby manned stealth fighters command swarms of collaborative combat aircraft (CCAs) for sensing, jamming, decoying, and striking.

This distributed force model directly addresses China’s A2/AD challenge by leveraging numerous lower-cost unmanned systems that collectively saturate Chinese air defenses.

The cost-exchange calculus fundamentally shifts when the U.S. military can deploy hundreds of small autonomous platforms against expensive SAM batteries, compelling China to either expend massive quantities of missiles (degrading resources for other missions) or accept degraded air defense coverage.

Integrated Air and Missile Defense for Forward Bases

The Enhanced Integrated Air and Missile Defense (EIAMD) system being deployed to Guam exemplifies a layered defense approach combining active and passive defense mechanisms.

The $8 billion EIAMD incorporates Aegis, Standard Missile 3 and 6 interceptors, THAAD, and the Typhon Mid-Range Capability System across 16 locations on Guam, providing 360-degree coverage.

This architecture enables U.S. forward bases to remain operational despite Chinese precision strike campaigns while serving as forward operating bases for counter-air operations throughout the Indo-Pacific.

Taiwan’s air defense strategy mirrors this integrated approach.

Rather than contesting the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) for air superiority—an objective Taiwan’s overwhelming numerical disadvantage makes prohibitive—Taiwan should pursue gradual air denial through distributed, layered defenses, including multiple batteries of advanced air defense systems that increase attrition rates and extend engagement depths.

Taiwan’s F-16V fighters, upgraded to F-16V standards with AN/APG-83 Scalable Agile Beam Radar, provide enhanced stealth resistance compared to legacy variants, extending detection ranges and improving simultaneous target tracking.

Cost-Imposition Military Strategy

The analyst before emphasised cost imposition rather than denial, which proves strategically sound when applied to counter-air defense operations.

Rather than seeking to neutralize all Chinese air defenses (an impossible objective), the U.S. military should focus on raising the perceived costs and risks of deploying air defense systems in contested configurations. This involves:

Destruction Risk

Through Persistent Targeting: Using distributed ISR networks to continuously track mobile air defense units, making SAM crews perceive their positions as persistently vulnerable.

Attrition Economics

Forcing China to expend increasingly expensive air defense missiles against low-cost drone swarms, depleting inventory faster than replenishment rates can support.

System Disruption

Through EW: Degrading command-and-control networks through distributed electronic warfare, reducing the effectiveness of individual air defense systems even without their physical destruction.

Operational Disruption

Making sustained air defense operations organizationally exhausting through continuous pressure, reducing crew efficiency, and creating decision-making paralysis.

Nonmilitary Dimensions of Counter-Air Defense Strategy

The U.S. should complement military measures with nonmilitary tools to undermine Chinese confidence in air power-dependent military solutions. These include:

Technology Containment

Accelerating export controls on advanced semiconductors and manufacturing equipment essential to Chinese radar, missile guidance, and autonomous systems development.

The demonstrated vulnerabilities of Pakistan’s HQ-9B system suggest that Chinese air defense technology—while advanced—remains dependent on continuous technological improvement cycles that U.S. containment policies can disrupt.

Diplomatic Isolation of Chinese Military Exports

Coordinating with allies and partners to restrict the sale of Chinese military systems and limit operational exchanges that would otherwise provide combat feedback for system improvement.

Recent Pakistani experience with HQ-9 failures represents precisely the kind of reality check on Chinese weapons quality that Beijing wants to avoid internationally.

Regional Alliance Strengthening

Building integrated air defense networks with allies (Japan, South Korea, Philippines, Australia, Taiwan) that collectively deny China room for regional air power projection.

Trilateral and quadrilateral defense integration exercises that demonstrate concrete interoperability create sunk costs for China attempting to disrupt these relationships through coercive measures.

Policy Recommendations for U.S. Defense Strategy

Prioritize Penetrating ISR Development

Accelerate RQ-180 production and deployment alongside advanced satellite-based ISR networks that can continuously map Chinese air defense positions and generate targeting data for suppression operations.

Establish SEAD as Core Capability

Make electronic warfare and SEAD competency the foundation of Air Force operational planning, with explicit budget allocation for DRFM jamming systems, electronic attack platforms, and training pipelines.

Accelerate NGAD and CCA Integration

Bring forward NGAD fighter procurement timelines to field operational systems by the early 2030s, prioritizing the CCA swarming architecture that provides an asymmetric counter to air defense saturation.

Regional IAMD Network Integration

Establish formally integrated air and missile defense command structures with Japan, South Korea, and the Philippines that move beyond episodic exercises toward persistent command-and-control integration.

Taiwan Air Defense Modernization

Accelerate delivery of air defense systems to Taiwan, focusing on distributed, mobile platforms optimized for attrition rather than concentrated high-value targets.

Support the development of indigenous drone and autonomous system capabilities.

Force Posture Transformation

Implement dispersed basing strategies that reduce reliance on vulnerable forward air bases, leveraging the rapid airfield repair capabilities demonstrated in Cold War operations and adapted for modern precision-strike environments.

Technology Containment Coordination

Establish a dedicated interagency mechanism to coordinate export controls, technology denial, and intelligence sharing to constrain Chinese air defense technology development trajectories systematically.

Conclusion

The article’s core insight—that deterrence increasingly depends on cost imposition rather than capability denial—fundamentally reframes how the United States should approach the defense of its air power against Chinese air power.

Rather than attempting to match Chinese air defense density or achieve unambiguous air superiority (increasingly unrealistic objectives), the U.S. military should pursue a long-term campaign combining penetrating ISR, distributed electronic warfare, swarm-based autonomous platforms, and regional alliance integration designed to impose unsustainable costs on Chinese air defense operations while making regional coercion unattractive for Beijing.

This strategy avoids the trap of seeking military dominance while still credibly conveying to the Chinese that military aggression against Taiwan or regional coercion would be “drawn out and exceedingly costly”—precisely the deterrent effect the original article recommends.

Success depends on sustained commitment to technological development, alliance integration, and a clear-eyed assessment that military competition with China will define the Indo-Pacific security environment for decades.