The US-China Race for Pacific Air Dominance: Geopolitical Drivers, Strategic Tensions, and Capabilities

Introduction

The competition between the United States and China for air superiority in the Indo-Pacific represents one of the most consequential military rivalries of the 21st century, with profound implications for regional stability and the global order.

This arms race is driven by fundamental geopolitical conflicts, strategic geography, and technological modernization efforts that reflect deeper structural tensions between the two powers.

Core Geopolitical Tensions

Taiwan and the Strategic Flashpoint

Taiwan remains the central geopolitical driver of this competition.

The US Defense Secretary stated that China’s President Xi has ordered the military to be capable of invading Taiwan by 2027, a timeline experts view as operationally plausible but strategically risky.

China views Taiwan as a core territorial interest and a non-negotiable element of national unification. At the same time, the US maintains strategic ambiguity—neither explicitly committing to defense nor renouncing it—while simultaneously strengthening Taiwan’s defensive capabilities.

China has demonstrated increasing military pressure through what military analysts characterize as “dress rehearsals for forced unification,” dispatching record numbers of aircraft near the island.

However, deliberate escalation appears constrained by cost-benefit calculations: a full-scale invasion would risk catastrophic losses, potential US or Japanese intervention, complete economic decoupling from the EU, disruption of the global microchip supply chain, and damage to Chinese coastal cities from Taiwan’s missile arsenal.

The First Island Chain as Strategic Encirclement

China’s military strategy is fundamentally shaped by what Beijing perceives as strategic encirclement through the First Island Chain—a chain of islands stretching from Japan through Taiwan to the Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore.

The US explicitly uses this geography to contain Chinese power projection, and Chinese strategists view the chain as a constraint on their maritime ambitions.

China’s core strategic objective is to “break through” this chain through military capability development, territorial assertion, and the construction of forward bases in the South China Sea.

Control of Taiwan would allow China to breach the First Island Chain entirely, enabling unrestricted access to the Pacific and decisively transforming the regional military balance in Beijing’s favor.

South China Sea Territorial Disputes

The South China Sea has become a tinderbox of escalating incidents.

The Philippines, which maintains overlapping claims with China and hosts a US mutual defense treaty, has experienced repeated confrontations with Chinese coast guard vessels, including rammings and water cannon attacks near Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal.

Chinese actions appear designed to establish administrative control through persistence and low-level coercion rather than dramatic military conquest.

Meanwhile, the Philippines has shifted strategy away from exclusive reliance on ASEAN consensus, expanding defense partnerships with the US, Japan, South Korea, India, and Canada to create a deterrent coalition.

This regional realignment reflects growing recognition that China’s assertiveness cannot be managed through dialogue alone.

Strategic Imperatives Driving Competition

Asymmetric Advantage Through Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD)

China has deliberately developed an extensive layered A2/AD system designed to prevent US military intervention during a Taiwan contingency.

This system pairs long-range missiles (DF-21D, DF-26), advanced surface combatants (Type 055 destroyers), anti-ship cruise missiles (YJ-21), and a dense sensor network to create multiple concentric threat rings around the First Island Chain.

The strategy aims to raise the costs of US intervention to prohibitive levels.

By threatening forward air bases in Okinawa, Japan, South Korea, and Guam with DF-series missiles, China seeks to compress US reaction times and force American naval forces to operate at greater distances from their preferred engagement zones, where they are more vulnerable.

This represents a deliberate challenge to the US doctrine of power projection and global reach.

US Carrier Force Vulnerability

The US Navy faces a critical vulnerability in the carrier air wing. Current carrier aircraft—dominated by the F/A-18 and F-35C—are increasingly mismatched to Pacific realities where adversary missile systems are rapidly improving.

Without a fast, long-range, heavily armed platform, American carriers may be forced to operate within lethal threat rings, jeopardizing both survivability and power projection.

Furthermore, the US carrier fleet is experiencing critical capacity shortages.

Delays in Ford-class carrier deliveries risk reducing the operational fleet below the congressionally mandated 11-ship minimum precisely when global tensions are rising across multiple theaters.

China, by contrast, is steadily expanding its carrier force with the construction of the Type 004 nuclear-powered carrier already underway.

Current Capabilities and Recent Developments

Chinese Advances

China’s commissioning of the Fujian in November 2025 represents a generational leap in naval air power.

The 80,000-ton conventionally powered carrier is equipped with electromagnetic aircraft launch systems (EMALS)—technology that matches US systems but is deployed vessel on a non-nuclear platform.

EMALS enables fighters to launch with full loads of fuel and weapons, dramatically increasing sortie rates and combat capabilities compared to China’s older ski-jump carriers (Liaoning and Shandong).

The Fujian can launch advanced aircraft including the J-35 stealth fighter, the J-15T heavy fighter, and the KJ-600 early warning aircraft, establishing a credible carrier strike capability for the first time.

China demonstrated these capabilities in September 2025 through video evidence of successful launches using EMALS.

China’s fighter force continues modernization with the J-20 (approximately 250 aircraft operational) and the emerging J-36 sixth-generation prototype.

The J-36 features a three-engine configuration and appears designed as a long-range strike platform potentially exceeding the J-20 in size and capability.

Military analysts note China began testing sixth-generation prototypes in December 2024, potentially placing the program three to four years ahead of the US F-47 sixth-generation initiative.

US Initiatives

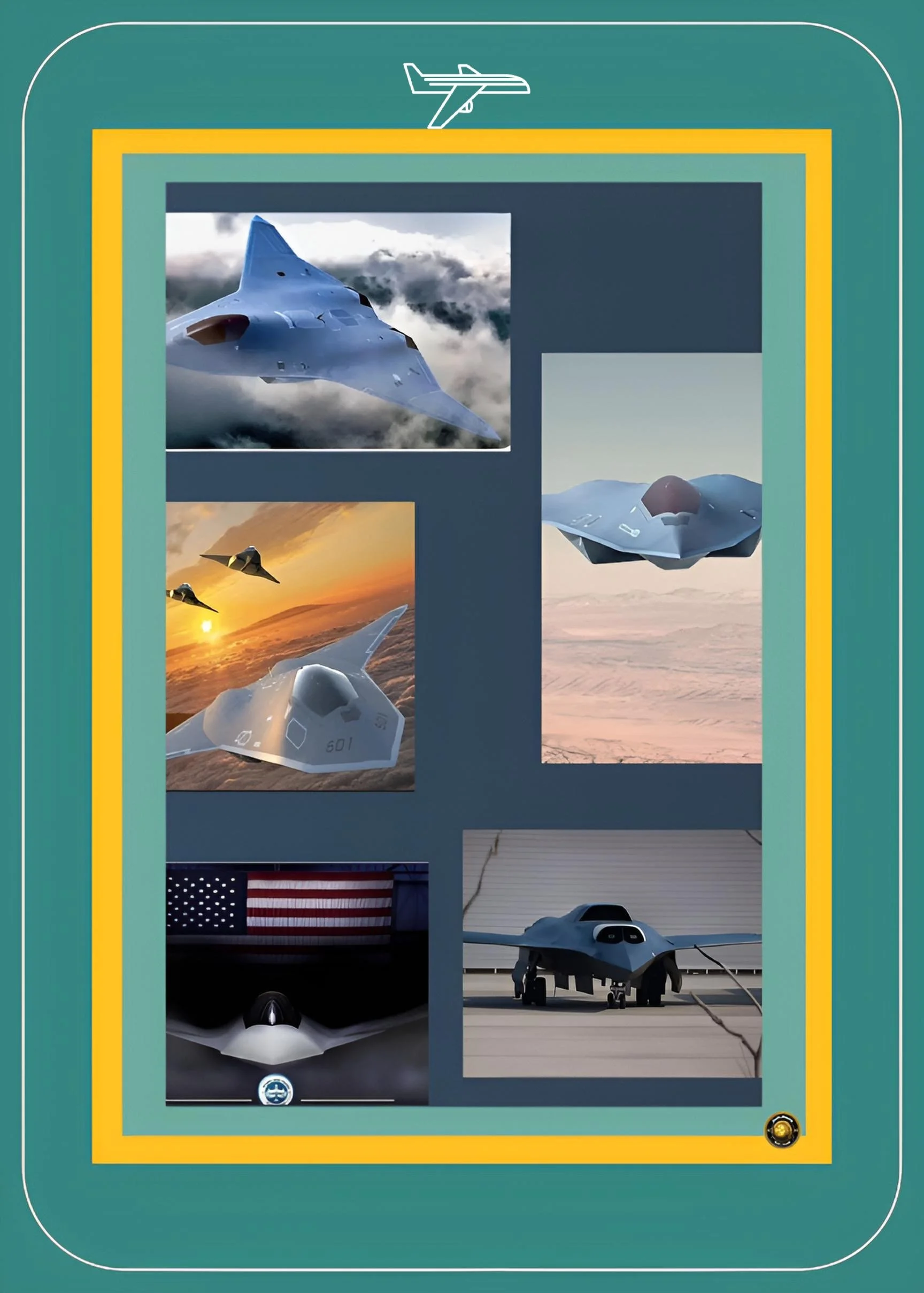

The US is attempting to revive lagging programs.

The Air Force confirmed production of the F-47 sixth-generation fighter at Boeing, with first flight scheduled for 2028 and 185 aircraft planned for acquisition.

However, the aircraft is not expected in service before the early 2030s—a critical gap given China’s timeline.

The Navy is also pressing for revival of the F/A-XX sixth-generation carrier-based fighter after the Department of Defense halted the program.

The Senate Appropriations Committee approved $1.4 billion in FY2026 defense spending to restart the initiative.

This reflects internal tension between naval leadership and defense officials over carrier aviation strategy.

Technological Comparison

Fifth-Generation Fighters

The US F-35 maintains advantages in sensor integration, stealth characteristics (particularly across-the-board low radar cross-section), and networking capabilities with other platforms and sensors.

However, the J-20 features a larger internal fuel capacity, longer unrefueled range, and larger weapon bays enabling it to carry long-range air-to-air missiles (reportedly extending to 180 miles) and precision strike weapons.

In naval warfare scenarios, the J-20’s greater range, payload, and apparent role as a maritime reconnaissance and strike platform make it a serious threat to US carrier operations and supporting logistics aircraft.

The emerging J-35, while smaller with more limited range (approximately 750 miles combat radius), represents a new generation optimized for carrier operations with reduced acoustic and electromagnetic signatures.

Carrier Systems

Remarkably, China’s Fujian has emerged as one of the world’s most advanced carriers.

The carrier successfully demonstrated EMALS operations in September 2025, launching the J-35 stealth fighter—making it the world’s first conventionally-powered carrier and first carrier globally capable of launching fifth-generation fighters using electromagnetic catapults.

The USS Gerald R. Ford, America’s only operational EMALS-equipped carrier, continues experiencing technical issues with its system, despite having abundant nuclear power available.

The Ford-class carrier program suffers from technical faults, industrial bottlenecks, and cost overruns that have delayed carrier deliveries and undermined fleet readiness.

No Ford-class carrier is publicly documented as fully certified for sustained F-35C operations at sea.

Strategic Implications and Deterrence Calculus

Shifting Military Balance

The emerging balance reflects China’s methodical investment in capabilities specifically designed to counter US advantages rather than mirroring them.

China is constructing a force architecture optimized for regional dominance within the First Island Chain rather than global power projection.

Its A2/AD system, carrier force, and sixth-generation fighter development collectively constrain US freedom of action in the Pacific.

Risks of Escalation vs. Incentives for Restraint

While cross-strait tensions have intensified, full-scale escalation remains unlikely for now. China’s command structure remains unsettled following corruption purges, and the strategic risks of unilateral action remain prohibitively high.

The Trump II administration has sent mixed signals regarding Taiwan, creating uncertainty about the reliability of US commitment.

Paradoxically, both nations’ capability investments create deterrence effects that can prevent conflict while simultaneously raising crisis instability risks.

A miscalculation during military exercises, an accidental collision, or “grey zone” operations that spiral unintentionally represent more realistic dangers than deliberate war.

Regional Realignment

The US-China competition is reshaping Asian regional security.

Allied nations including Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Australia are accelerating defense spending, acquiring longer-range weapons systems, hardening military bases, and developing alternative communication networks to reduce vulnerability to Chinese A2/AD systems.

Regional powers view the competition as neither inevitable US victory nor inevitable Chinese hegemony, but rather an evolving balance requiring defensive hedging.

Conclusion

The US and China are fundamentally competing for control of the Western Pacific through military modernization driven by Taiwan’s strategic position, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and competing visions of regional order.

China seeks to break through what it views as US-imposed encirclement; the US seeks to maintain maritime dominance and freedom of navigation.

Both nations are making rapid technological advances, with China closing capability gaps in carrier aviation and fighter aircraft while the US struggles with carrier program delays and force structure shortages.

The race will likely define Indo-Pacific security for the next decade, with profound implications for Taiwan, regional powers, and the global economy dependent on Pacific sea lanes.