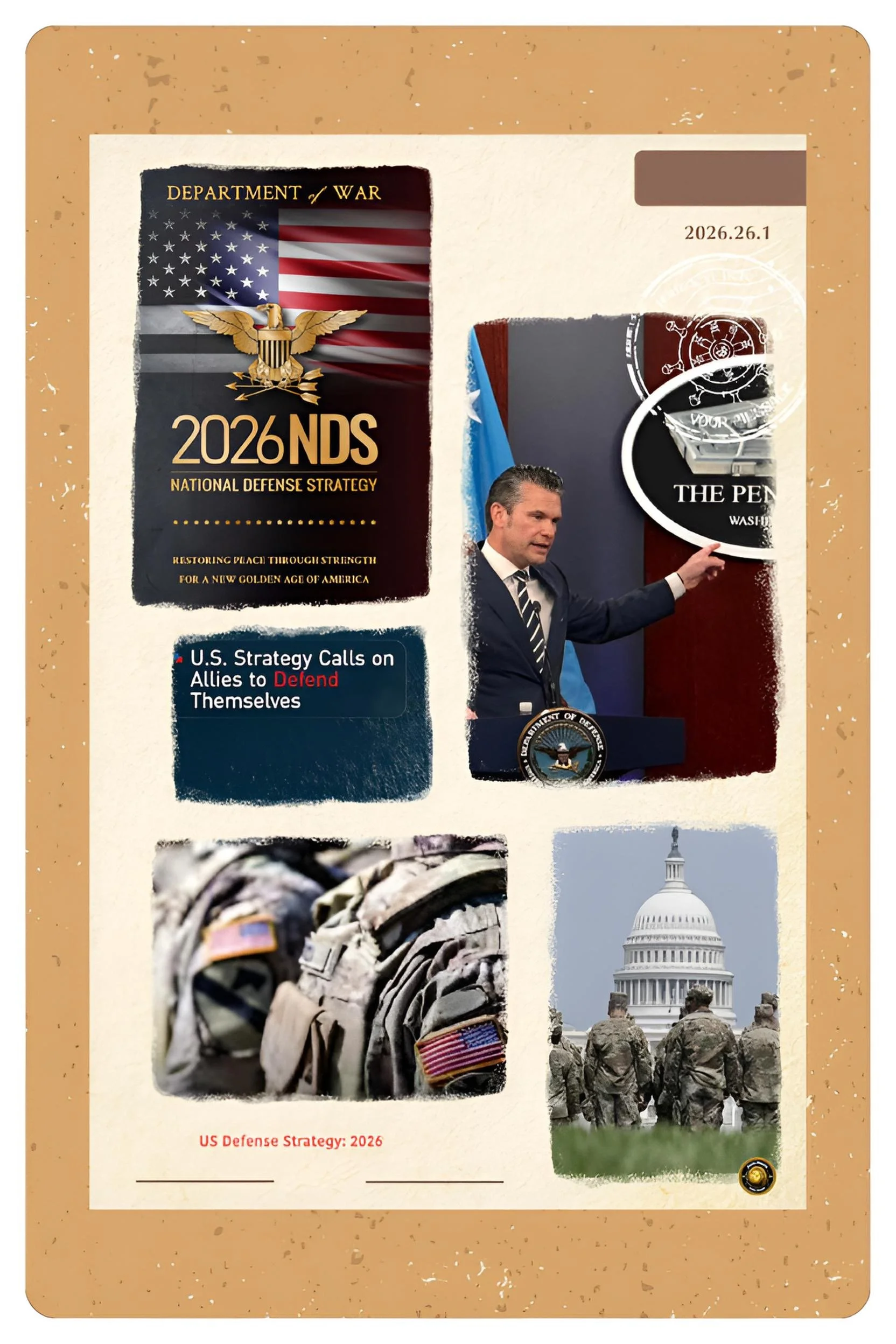

Pentagon Preparedness for Full-Scale Military and Economic Confrontation with China: A Comprehensive Strategic Assessment

Executive Summary

Pentagon’s Hidden Vulnerability: Classified Assessments Reveal U.S. Military May Be Unprepared for China Confrontation

The Pentagon’s preparedness for a full-scale military and economic altercation with China presents a paradoxical picture of simultaneous technological superiority and emerging vulnerabilities.

Recent classified assessments, including the secretive “Overmatch Brief” disclosed by The New York Times in December 2025, reveal profound structural weaknesses in American military posture that contradict decades of strategic doctrine asserting undisputed American dominance in the Indo-Pacific.

While the United States maintains advantages in global reach, technological sophistication, and advanced weapons platforms, China’s asymmetric strategy of developing cheaper, rapidly deployable systems designed to overwhelm American assets—combined with Beijing’s exploitation of critical supply-chain dependencies and cyber vulnerabilities—presents an existential challenge that the Pentagon is demonstrating inadequate readiness to confront.

The acceleration of weapons production initiatives, heightened military expenditures, and strategic repositioning in Southeast Asia indicate recognition of the crisis, yet Pentagon officials privately acknowledge that current force structure, industrial capacity, and doctrine remain fundamentally misaligned with the demands of potential conflict over Taiwan within the narrowing strategic window of 2027.

Introduction

America’s Military Advantage Over China Is Narrowing Faster Than Washington Admits: Pentagon Insiders Warn

The relationship between the United States and the People’s Republic of China has entered a qualitatively new phase of strategic competition, one defined not by containment strategies or economic leverage alone, but by the tangible possibility of direct military confrontation.

The Taiwan question serves as the primary flashpoint, with intelligence assessments confirming that Chinese President Xi Jinping has directed the People’s Liberation Army to achieve operational readiness for a military option against Taiwan by 2027—a deadline that has concentrated American strategic planning into an increasingly urgent posture.

The December 2024 Pentagon report on Chinese military power, the 24th iteration of this annual assessment, alongside classified evaluations such as the Overmatch Brief, reveals that the technological, industrial, and operational gap between American and Chinese capabilities has narrowed dramatically over the past decade.

These documents present a sobering departure from the conventional wisdom that has dominated policy circles for years: the notion that American military superiority in the Pacific is so overwhelming that Beijing would be deterred from any military adventurism.

Instead, Pentagon assessments now project scenarios in which American carrier battle groups are vulnerable to targeted destruction, fighter jets cannot reach contested airspace without attrition that exceeds replacement capacity, and supply chains critical to sustained military operations would be severed within days of conflict initiation.

The Pentagon’s readiness for such a confrontation—both militarily and economically—remains inadequate relative to the challenge posed by a peer-competitor state with regional geographic advantages and a centrally-planned defense industrial mobilization strategy.

Key Developments and Strategic Context

Nuclear Escalation and Strategic Deterrence

China’s nuclear modernization trajectory represents perhaps the most consequential long-term shift in the strategic balance.

The Pentagon now estimates that China possesses over 600 operational nuclear warheads, an increase from approximately 500 in the previous year’s assessment, with projections indicating China will possess more than 1,000 warheads by 2030 and continue expanding beyond that timeline through 2035.

This represents a qualitative acceleration in China’s nuclear build-up, driven by Beijing’s perception that it faces potential military competition, crisis, and possibly conflict with the United States, with Taiwan as the most probable flashpoint.

Particularly alarming is China’s development of fractional orbital bombardment systems and hypersonic glide vehicles, positioning Beijing with what defense officials describe as “the world’s leading hypersonic missile arsenal.”

More ominously, the Pentagon’s December 2024 assessment notes that the People’s Liberation Army is actively implementing an “early warning counterstrike” posture this decade, functionally equivalent to the Soviet “launch on warning” doctrine that was abandoned by the United States decades ago due to its destabilizing implications.

This means that China is positioning its nuclear forces such that a detected incoming American strike would trigger an automatic Chinese retaliatory response before American weapons arrive at their targets, fundamentally altering the logic of deterrence that has underpinned American strategic doctrine.

The assessment further emphasizes that China’s “force modernization suggests that it seeks the ability to inflict far greater levels of overwhelming damage to an adversary in a nuclear exchange,” indicating that Beijing is not content with assured retaliation but rather seeks to maximize casualties and destruction in any nuclear confrontation.

Conventional Military Capabilities and Regional Military Balance

Beyond the nuclear realm, China’s conventional military modernization presents asymmetrical challenges that the Pentagon’s force structure is ill-equipped to address.

The People’s Liberation Army Navy now constitutes the numerically largest navy in the world with 370 ships and submarines, compared to the American fleet of approximately 330 vessels, with the Department of Defense projecting that China will possess 395 ships by the end of 2025 and 435 by 2030.

This numerical advantage, however, masks a more sophisticated strategic development: the composition of the Chinese fleet increasingly emphasizes modern multi-role platforms featuring advanced anti-ship, anti-air, and anti-submarine weapons and sensors, with particular emphasis on distributed, redundant systems designed to overwhelm American defensive architectures.

The PLA’s submarine fleet, similarly positioned for high readiness with increasing focus on real-world contingency training conducted at greater distances from shore, represents a capability that the American Navy has not faced since the end of the Cold War.

Chinese advances in anti-ship warfare technology, particularly the development of hypersonic missiles such as the YJ-21 launched from Type 055 guided-missile cruisers, directly threaten the signature platform of American power projection: the aircraft carrier.

The Pentagon’s analysis indicates that during war-game simulations, Chinese forces repeatedly succeeded in striking American carriers at standoff ranges where American aircraft could not mount effective defense.

In terms of air power, while the United States maintains quantitative superiority with 13,043 military aircraft compared to China’s 3,309, this aggregate figure obscures critical vulnerabilities.

American air superiority doctrine has been predicated on global power projection using large, expensive platforms such as the F-35 fighter jet and the B-2 stealth bomber.

China’s acquisition of approximately 1,212 fighter aircraft, combined with advances in surface-to-air missile technology and the development of stealth aircraft such as the J-35 carrier fighter and the H-20 stealth bomber, has created an anti-access/area-denial environment that fundamentally constrains American operational options in the Western Pacific.

With respect to ground forces, while the United States maintains quantitative superiority in armored fighting vehicles (391,963 compared to China’s 144,017), China possesses substantially more main battle tanks (6,800 versus America’s 4,640), self-propelled artillery (3,490 versus 671), and multiple-launch rocket systems (2,750 versus 641), reflecting a doctrine optimized for continental operations and regional control rather than global expeditionary warfare.

The Overmatch Assessment and Pentagon Vulnerabilities

“We Are Not Ready”: Pentagon Documents Expose Critical Gaps in American Defenses Against China

The classified Overmatch Brief, prepared by the Pentagon’s Office of Net Assessment and disclosed by The New York Times in December 2025, represents the first unambiguous official acknowledgment that the United States faces potential military inferiority in a Taiwan conflict scenario.

The assessment, which spans every major component of American war-fighting capability including fighter aircraft, aircraft carriers, missile defense networks, space-based communications systems, and cyber operations, concludes through multiple war-gaming scenarios that Chinese forces would likely succeed in neutralizing or destroying critical American assets before they could be effectively deployed.

Specific examples cited in available reporting include the USS Gerald R. Ford aircraft carrier—the Navy’s most advanced platform at a cost of $13 billion—being repeatedly struck in simulations by Chinese long-range missiles, rendering the vessel ineffective and destroying its deterrent value.

Similarly, the F-35 fighter aircraft, despite over 20 years of development and a total program cost exceeding $1.7 trillion, is identified as plagued by persistent structural flaws that limit its operational effectiveness in a contested air environment.

The Overmatch Brief further emphasizes that American doctrine has become fundamentally misaligned with the operational realities of potential conflict in the Pacific.

The American military continues to invest heavily in large, complex, and increasingly difficult-to-defend platforms rooted in Cold War-era doctrine predicated on American air and sea superiority.

China, conversely, has pursued a strategy of producing large numbers of cheaper, redundant weapons systems specifically designed to overwhelm or disable American assets through sheer volume and technological sophistication.

This creates a fundamental strategic contradiction: American strategy depends on denying Chinese forces the ability to concentrate overwhelming force at points of their choosing, yet Chinese strategy is explicitly designed to overcome American advantages through redundancy, saturation attacks, and exploitation of geographic proximity to Taiwan.

The logical consequence is that American superiority in individual weapons systems becomes irrelevant when confronted by Chinese superiority in numbers, redundancy, and production capacity.

The Pentagon’s assessment notes that in a three-week Taiwan conflict scenario, American forces would require approximately 5,000 long-range precision-guided missiles, a stockpile that does not exist.

Critical shortages would emerge within the first week, forcing American commanders to choose between abandoning operational concepts or accepting catastrophic attrition.

Cyber Vulnerabilities and Infrastructure Penetration

A dimension of American vulnerability that extends beyond conventional military calculus concerns the digital and cyber infrastructure upon which modern military operations depend.

The Overmatch Brief devotes significant analytical attention to American cyber weaknesses, citing specific intrusions by Chinese state-linked hacking groups such as Volt Typhoon, which has penetrated electrical systems, water supplies, and communications infrastructure tied to United States military bases.

More alarming still is reporting from July 2025 that the Department of Defense has outsourced sensitive IT maintenance to Microsoft engineers located in mainland China, granting Beijing authorized access to Pentagon systems for nearly a decade.

Subsequent investigations revealed that Chinese Ministry of State Security-affiliated hackers have stolen sensitive records from defense contractors and university programs engaged in classified research, including theft of plans for the F-35 fighter jet from Lockheed Martin subcontractors—intelligence that the Pentagon acknowledges expedited China’s development of its own fifth-generation J-31 fighter.

Beyond espionage, Chinese cyber operations have focused increasingly on what defense analysts term “operational preparation of the battlefield,” pre-positioning exploitable vulnerabilities within American critical infrastructure including telecommunications networks (via the “Salt Typhoon” campaign), power grids and water systems (via “Volt Typhoon”), and U.S.-Taiwanese communications networks (via “Flax Typhoon”).

These operations are not designed to achieve immediate operational effects but rather to create latent vulnerabilities that Beijing could activate at a time of its choosing, potentially paralyzing American military command and control structures during crisis or conflict initiation.

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities and Industrial Base Incapacity

The Pentagon’s assessment of American readiness must also incorporate the critical vulnerabilities embedded within the American defense industrial base and supply chains.

In April 2025, the Government Accountability Office reported that the United States defense industrial base and all branches of the American military depend heavily on materials and components produced by China and countries with adversarial intentions toward the United States.

Specifically, the GAO identified that China, as a global supplier of critical minerals including gallium and germanium essential for military-grade electronics, illustrated its leverage by imposing export restrictions on these materials in 2024, restrictions that disrupted American military production and provided Beijing with significant negotiating leverage during trade discussions.

In a more startling instance, Lockheed Martin identified prohibited Chinese magnets in the F-35 supply chain and notified the Department of Defense in 2023 and 2024, forcing the department to pause manufacturing for several months while alternative suppliers were identified.

The United States naval submarine production program, critical to maintaining underwater deterrence, faces similar constraints: submarines require titanium castings for critical vessel components, yet the United States currently lacks the capacity to cast titanium due to limited supply and outdated forging equipment.

Rare earth elements, essential for producing everything from radar systems to jet engines, remain heavily dependent on Chinese extraction and processing, with China controlling approximately 70 percent of global rare earth mining and 90 percent of processing capacity.

In October 2025, China expanded its export control regime through six separate notices targeting rare earth production technologies, lithium battery production equipment, and superhard materials with defense applications, simultaneously adding 14 Western entities to its “unreliable entity list.”

The timing of these controls—announced hours before a corresponding American sanctions announcement—demonstrated Beijing’s strategic coordination of economic and political measures to maximize American vulnerability.

Broader assessments indicate that American dependence on Chinese supply chains extends to pharmaceuticals, electrical equipment, and specialized manufacturing components, creating scenarios in which Beijing could systematically sever American access to critical inputs through coordinated export controls, thereby degrading American military capability without firing a shot.

Pentagon Ammunition Stockpile Deficiency

The Pentagon’s recent accelerated weapons production initiatives directly reflect recognition of catastrophic ammunition and munitions shortfalls.

In September 2025, the Pentagon issued directives to missile suppliers to dramatically increase production of twelve critical weapons systems, including Patriot air defense interceptors, long-range anti-ship missiles, and joint air-to-surface standoff missiles.

The directives, issued through a Munitions Acceleration Council chaired by Deputy Defense Secretary Steve Feinberg and featuring weekly calls with major defense contractors, called for “doubling or even quadrupling” production at a “breakneck schedule.”

The Pentagon targeted achieving a 2.5 times increase in production volumes within six, eighteen, and twenty-four months—timelines that defense industry analysts acknowledge are extraordinarily ambitious given current manufacturing constraints and the need to source critical materials and components.

This emergency mobilization directly responds to assessment that American munitions stockpiles, particularly long-range precision-guided missiles, are insufficient for sustained high-intensity conflict.

A January 2023 Center for Strategic and International Studies analysis, validated by subsequent Pentagon war games, projected that in a three-week Taiwan conflict, American forces would exhaust approximately 5,000 long-range missiles, with critical shortages occurring within the first operational week.

The United States cannot currently produce this quantity of long-range missiles within the required timeframe, creating a situation where American operational plans fundamentally depend on capability that does not exist.

The Pentagon’s response has included efforts to develop low-cost missile systems in cooperation with allies, including the Coalition Affordable Maritime Strike Weapon System (CAMS) designed with allied Japanese and Australian manufacturers, and the acceleration of existing programs such as the Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) and Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) production.

However, these initiatives, while necessary, cannot fully resolve the underlying structural problem: American industrial capacity for rapid munitions production has atrophied over decades of uncontested military dominance, while Chinese capacity for rapid weapons system production has expanded exponentially.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: The Architecture of American Vulnerability

Structural Misalignment Between Doctrine and Reality

The fundamental cause of American military vulnerability to China derives from a structural misalignment between Cold War and post-Cold War doctrine, designed for operations against militarily inferior adversaries, and the present strategic reality of competition with a peer competitor state possessing regional geographic advantages and a centrally-planned military modernization strategy.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, American military planning incorporated assumptions of uncontested air and sea superiority, vast technological advantages, and the ability to project overwhelming force across global distances.

These assumptions generated doctrine and force structure predicated on small numbers of expensive, technologically sophisticated platforms (such as the F-35, USS Ford aircraft carriers, and B-2 stealth bombers) that were designed to prevail against qualitatively inferior adversaries through technical superiority.

China’s asymmetric response has been to develop doctrine and force structure predicated on large numbers of cheaper, rapidly deployable systems designed to exploit American vulnerabilities precisely at the point where American doctrine assumes superiority.

This creates a fundamental strategic contradiction: American strategy depends on denying Chinese forces the ability to concentrate overwhelming force at points of their choosing, yet Chinese strategy is explicitly designed to overcome American advantages through redundancy, saturation attacks, and exploitation of geographic proximity to Taiwan.

The logical consequence is that American superiority in individual weapons systems becomes irrelevant when confronted by Chinese superiority in numbers, redundancy, and production capacity.

Industrial Base Decay and the Long Peace Dividend

The cause of American munitions stockpile deficiency and industrial base incapacity derives directly from the strategic environment that followed the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991.

The “peace dividend” of the 1990s and 2000s entailed massive contraction of American defense industrial capacity, with consolidation of defense contractors, closure of production facilities, and the systematic outsourcing of supply-chain components to lowest-cost providers, many located in China and other countries with strategic interests opposed to American security.

The assumption underpinning these decisions was that future conflicts would resemble recent American experience: wars against technologically inferior adversaries (Iraq, Afghanistan) in which attrition rates were manageable and the United States possessed overwhelming superiority in precision weaponry and logistics.

The consequence of this rationalization was that American defense industrial capacity for rapid munitions production contracted dramatically, with private industry having little incentive to maintain surge capacity for scenarios that were assumed to be unlikely.

The Ukraine war, beginning in February 2022, exposed these vulnerabilities by demonstrating that modern conventional warfare involves sustained, high-intensity attrition that depletes munitions stockpiles at rates that American production capacity cannot sustain.

The Pentagon’s recognition that potential Taiwan conflict would exhaust American missile stockpiles within days represents the logical consequence of decisions made over three decades to optimize for technological superiority rather than industrial redundancy and surge capacity.

China’s Military-Civil Fusion Strategy and Technology Transfer

The cause of China’s accelerating military modernization, which has allowed the PLA to close the capability gap with the United States at an unprecedented pace, derives from the deliberate implementation of what the Pentagon terms “Military-Civil Fusion” (MCF) strategy.

The MCF integrates civilian technological advancement into military applications by leveraging academic institutions, private-sector research, and commercial enterprises to systematically advance military capabilities.

Critically, Beijing accomplishes much of this technology transfer through explicit cooperation with American, European, and Japanese firms that are attracted by commercial opportunities in the Chinese market, combined with more covert intelligence operations that acquire sensitive military and technological information.

The Pentagon’s assessment notes that Chinese military planners have actively pursued theft of classified information regarding advanced American weapons systems, including aircraft, missile guidance systems, and naval technologies.

A specific example cited in Pentagon reports involves Chinese intelligence services stealing plans for the F-35 from Lockheed Martin subcontractors, information that was then integrated into the design and production of China’s J-31 stealth fighter.

Rather than independently developing stealth technology through decades of research and experimentation, as the United States did, China was able to accelerate development timelines by directly acquiring American classified technical information.

The logical consequence is that China’s military capabilities are advancing at a compressed timeline compared to historical patterns, allowing the People’s Liberation Army to achieve operational parity with American forces at a much earlier date than would be possible through indigenous development.

Supply Chain Interdependence and Economic Leverage

The fundamental cause of American vulnerability to Chinese economic warfare derives from deliberate integration of the Chinese economy into the American supply chain over the past three decades, a strategic choice made by American policymakers and private-sector leaders in pursuit of economic efficiency and profit maximization.

Chinese control of rare earth element extraction and processing, critical mineral production, pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity, and specialized electronic components represents not primarily a security oversight but rather the logical consequence of economic decisions to outsource these capabilities to lower-cost providers.

China’s strategic positioning of itself as the indispensable supplier for critical inputs to American military production was accompanied by explicit political decisions by Beijing to restrict exports of these materials at moments of geopolitical tension, demonstrating that China views supply-chain control as a weapon in the broader strategic competition with the United States.

The October 2025 expansion of Chinese export controls on rare earth technologies, lithium battery equipment, and superhard materials was explicitly coordinated with Chinese military expansion in the Taiwan Strait, illustrating Beijing’s integration of economic and military strategy.

The logical consequence is that American military readiness is constrained not by the availability of weapons systems or personnel but by the availability of critical materials and components controlled by a strategic competitor, a vulnerability that cannot be easily or rapidly remedied through policy adjustment or increased military spending.

Facts and Concerns: The Reality of American Preparedness Gaps

Quantified Capability Deficits

The Pentagon’s own assessments provide quantified evidence of critical capability gaps. In war-game scenarios involving Taiwan contingencies, American forces are projected to exhaust long-range precision-guided missile stockpiles within seven to ten days, at which point operational effectiveness collapses.

The Department of Defense has explicitly stated that current American ammunition stockpiles are insufficient for sustained high-intensity conflict with a peer competitor, motivating the emergency acceleration of munitions production initiatives launched in 2025.

Specific assessments indicate that American submarine production capacity cannot meet replacement rates for vessels lost in potential conflict, with the Navy’s Columbia-class submarine program being constrained by titanium-casting limitations and specialized manufacturing bottlenecks.

The F-35 fighter program, despite three decades of development and $1.7 trillion in cumulative investment, continues to be plagued by software integration issues, structural limitations in design, and Chinese-origin critical components that create supply-chain vulnerabilities.

Pentagon officials have privately acknowledged that the F-35 remains unsuitable for high-intensity operations in a contested environment against a peer competitor possessing advanced air defense systems and fighters comparable in technological sophistication.

The air defense architecture defending American forces in the Pacific, predicated on older Patriot and AEGIS systems, faces a rapidly expanding inventory of Chinese anti-ship and anti-air missiles designed to saturate American defensive capacity through volume and hypersonic speed.

Organizational and Doctrinal Inertia

American military culture, shaped by three decades of technological and tactical dominance, demonstrates significant institutional resistance to the doctrinal and organizational adaptations necessary for competition with peer competitors.

The current force structure, procurement processes, and operational concepts remain optimized for wars against technologically inferior adversaries conducted with overwhelming local superiority in air and naval assets.

Adaptation to a strategic environment in which American forces cannot assume local superiority, possess no margins for attrition, and must sustain operations under conditions of contested logistics requires fundamental organizational change that military institutions have historically been slow to undertake.

Pentagon leadership has acknowledged this challenge through the emphasis on “acquisition reform” and the mandate to transform the military to a “wartime footing,” directives that represent recognition of the inadequacy of peacetime institutional approaches to mobilize for conflict.

However, the Pentagon’s historical record in organizational reform, particularly regarding acquisition and industrial base restructuring, demonstrates limited capacity for rapid and fundamental change.

The services continue to advocate for major weapons platforms (such as the USS Ford carrier and F-35 fighter) that war-game analyses suggest are vulnerabilities rather than advantages, indicating that service interests and doctrinal conservatism continue to constrain strategic adaptation.

Technological Vulnerabilities in Emerging Domains

American vulnerabilities extend beyond conventional military domains to emerging technological areas in which China is actively developing superiority.

Chinese advances in hypersonic weapons, directed-energy systems, and artificial intelligence-enabled autonomous weapons create potential asymmetries that American defense planning has inadequately addressed.

The Pentagon’s December 2024 report emphasizes that China now possesses “the world’s leading hypersonic missile arsenal,” with multiple fielded systems designed to penetrate American air defenses and destroy American assets at extended ranges.

The United States, conversely, remains in early development phases for hypersonic strike weapons, with no fielded systems yet available in operationally significant numbers.

Similarly, American space-based surveillance and communications systems, upon which modern military operations fundamentally depend, are increasingly vulnerable to Chinese anti-satellite weapons, including kinetic kill vehicles, directed-energy weapons, and electromagnetic pulse systems.

The Pentagon’s recognition of these vulnerabilities is evident in the emphasis on space resilience and rapid replacement of satellite capability, yet current American industrial capacity for space system production remains constrained relative to the scale of potential losses in a high-intensity conflict.

Regional Military Balance and Deterrence Erosion

The cumulative effect of the military developments outlined above is a progressive erosion of American deterrent capability in the Indo-Pacific region.

For decades, American deterrence strategy has rested on assumptions that American forces could rapidly deploy to the Western Pacific, establish air and sea superiority, and impose costs on any Chinese military action sufficiently high to deter Chinese aggression.

This deterrent logic is progressively undermined as Chinese conventional capability advances and the gap between American and Chinese readiness narrows.

The Lowy Institute’s 2025 Asia Power Index assessment documented that “China continues to diminish the U.S. advantage in military capabilities,” with the U.S. lead in this category declining by approximately one-third compared to 2015 levels.

The specific areas of Chinese advancement—particularly in naval and air combat capabilities—directly threaten the geographic domains through which American power must be projected to defend Taiwan.

The logical implication is that by the time American forces are positioned to undertake military operations in defense of Taiwan, the window for effective intervention may have closed, either through successful Chinese military operations or through escalation to a level of intensity that American political decision-making cannot sustain.

The 2027 Temporal Dimension and Narrowing Strategic Windows

A distinctive feature of current strategic analysis is the recognition that the window for American military intervention in a Taiwan scenario may be foreclosing within a remarkably narrow timeframe.

Intelligence assessments confirm that President Xi Jinping has directed the People’s Liberation Army to achieve operational readiness for a Taiwan military option by 2027, a deadline that functions as both a strategic objective and a planning benchmark for both American and Taiwanese defense planners.

This artificial but strategically consequential deadline concentrates consideration of the Taiwan question into a specific temporal window, one during which American military readiness improvements must be accomplished.

The Pentagon’s emphasis on accelerated weapons production, allied defense spending increases, and military-to-military exercises reflects recognition that the window for preparation is narrow.

Conversely, China’s military modernization schedule, organized around the 2027 deadline, has achieved sufficient momentum that significant reductions in capability advancement are unlikely regardless of American policy adjustments.

The logical implication is that the military balance in the Indo-Pacific will continue to evolve in China’s favor over the next two years, a progression that American policy has minimal capacity to reverse but potentially significant capacity to slow or complicate.

Future Steps: Pentagon Adaptation and Structural Reform

Industrial Base Mobilization and Surge Capacity

The Pentagon’s primary strategic imperative, implicitly recognized in current policy initiatives, is to fundamentally restructure American defense industrial capacity from a peacetime model optimized for technological sophistication and profit maximization to a wartime model capable of rapid, large-scale production of weapons systems designed for attrition-intensive conflict.

This requires substantially increased defense spending, with leading defense analysts arguing for increases to 5 percent of gross domestic product—a level consistent with Cold War defense spending and substantially above current levels near 3 percent.

Increased spending alone, however, is insufficient; the Pentagon must simultaneously restructure acquisition processes to prioritize speed and volume over technological perfection, abandon or fundamentally redesign weapons programs that war-game analysis suggests are liabilities rather than assets, and actively reconstruct manufacturing capacity for munitions and critical components that has been outsourced or eliminated over the past three decades.

Specific initiatives announced in 2025, including the Munitions Acceleration Council and the emphasis on rapid prototyping and production of lower-cost, redundant weapons systems, represent necessary steps in this direction.

However, the scale and pace of these initiatives remain inadequate relative to the magnitude of the challenge.

The Pentagon’s stated objective of doubling or quadrupling munitions production within eighteen to twenty-four months is ambitious but still falls short of the production rates that Pentagon war-gaming suggests would be necessary for sustained conflict.

Ultimately, this dimension of American preparedness requires that the defense industrial base be placed “on a wartime footing,” meaning that surge production capacity becomes a permanent feature of American defense planning rather than an emergency response that occurs only during active conflict.

Doctrinal Adaptation and Force Structure Redesign

The Pentagon must undertake fundamental revision of military doctrine to address the specific nature of peer competition with China in geographic domains where China enjoys positional advantages.

This requires explicit recognition that American forces cannot assume air and sea superiority in the Western Pacific and therefore must reorganize around concepts of distributed, resilient operations that emphasize redundancy over concentration.

The Trump administration’s emphasizing of increased military presence in Southeast Asia through rotational deployments rather than fixed bases represents a movement in this direction, creating geographic distribution that makes American forces more resilient to concentrated Chinese missile attacks.

However, full implementation of this strategic concept requires fundamental redesign of American naval doctrine (emphasizing smaller, more numerous vessels over capital ships), air operations doctrine (emphasizing distributed operations rather than centralized control), and logistics architecture (emphasizing forward-positioned supplies rather than centralized supply depots).

Such fundamental redesign challenges the interests of services that have built institutional identities around large capital ships and advanced fighter aircraft, creating organizational resistance to necessary adaptation.

Allied Capability Development and Collective Defense Architecture

The Pentagon’s recognition that American forces alone cannot defend Taiwan against a full-scale Chinese invasion has motivated increased emphasis on allied capability development and integrated defense architecture among Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Australia.

The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy and the Pentagon’s 2025 Indo-Pacific strategic positioning emphasize that defending Taiwan will require military overmatch achieved through collective allied effort rather than American unilateral capability.

This requires not merely increased American arms sales to Taiwan (including the December 2025 package valued at over $10 billion) but systematic integration of Taiwanese, Japanese, Australian, and Philippine capabilities into unified command structures and coordinated operational planning.

Taiwan’s announcement in December 2025 of a $40 billion defense spending program, increasing defense spending to 3.5 percent of gross domestic product with plans to reach 5 percent by 2030, represents movement toward greater self-defense capacity.

Japan’s incremental enhancement of its military capability, including recognition of collective defense obligations, similarly represents necessary allied adaptation.

However, the extent to which allied forces can substitute for American capability gaps remains uncertain, particularly given the geographic proximity of Chinese forces to Taiwan and the rapid timeline of potential Chinese military operations.

Supply Chain Decoupling and Industrial Resilience

The Pentagon must simultaneously undertake systematic restructuring of supply chains to reduce American dependence on Chinese materials and components critical to weapons system production.

This requires investment in domestic capacity for rare earth element processing, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and specialized electronics, an undertaking that requires both government subsidization and private-sector restructuring.

The administration’s approach, emphasizing tariffs and export controls as instruments of supply-chain restructuring, creates tensions with the objective of maintaining allied coalition unity and managing economic consequences of disrupted global trade.

However, the strategic imperative for supply-chain autonomy is clear: American military capability cannot be constrained by Chinese control of critical inputs, a vulnerability that transcends questions of tariff policy or trade negotiation.

Conclusion

Your Missiles Won’t Work: How China Designed Weapons Specifically to Defeat America’s Best Assets

The Pentagon is demonstrably not fully prepared for a full-scale military and economic altercation with China within the foreseeable strategic horizon.

While American military forces retain technological advantages in select domains and organizational experience that Chinese forces do not yet possess, the cumulative assessment of Pentagon documents, war-gaming analyses, and classified evaluations reveals that American readiness for a high-intensity, peer-competitor conflict remains fundamentally inadequate.

The Overmatch Brief’s acknowledgment of potential American military defeat in a Taiwan conflict scenario represents the most candid official recognition of this inadequacy, though the fundamental vulnerabilities it documents have been evident to informed observers for several years.

The narrowing temporal window created by the 2027 deadline for Chinese military readiness against Taiwan creates an artificial urgency that concentrates strategic questions into a specific timeframe in which American military adaptation is difficult but potentially still achievable.

The Pentagon’s recent acceleration of weapons production, increased military presence in the Indo-Pacific, and emphasis on allied capability development represent necessary adaptations, yet they remain inadequate in scale and pace relative to the challenge.

Fundamental restructuring of American defense industrial capacity, military doctrine, force structure, and strategic alliance architecture would be required to achieve genuine readiness for peer competition with China.

Such restructuring would require sustained bipartisan commitment to increased defense spending, institutional willingness to abandon legacy weapons programs, and strategic patience to implement complex organizational reforms over multiple years.

Whether American political institutions and military establishment can accomplish this transformation within the narrowing strategic window remains the central question for American national security strategy in the coming years.

The Pentagon’s current trajectory suggests incremental adaptation rather than the fundamental restructuring that strategic competition with China actually requires, a mismatch between challenge and response that carries profound implications for the future of American power in the Indo-Pacific region and the global balance of power more broadly.