The Making of the Modern Middle East: Key Events, Narratives, and Geopolitical Lessons from Scott Anderson’s “Lawrence in Arabia”

Forward

Scott Anderson’s masterwork “Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East” provides a profound analysis of how World War I’s aftermath created the foundational dynamics that continue to define Middle Eastern geopolitics today.

Through meticulous research and compelling narrative, Anderson reveals how a handful of young operatives, working largely without oversight, shaped decisions that would reverberate across generations.

The book’s central thesis demonstrates that the artificial borders, broken promises, and imperial machinations of 1916-1922 established patterns of intervention, betrayal, and conflict that remain strikingly relevant to contemporary global politics.

Key Historical Events and the Architecture of Betrayal

The Arab Revolt and Competing Promises (1916-1918)

The Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule began in June 1916, initiated by Emir Hussein of Mecca based on British assurances of Arab independence.

The British had promised Hussein through the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence that Arab support against the Turks would be rewarded with independence over Greater Syria, Iraq, and the Arabian Peninsula.

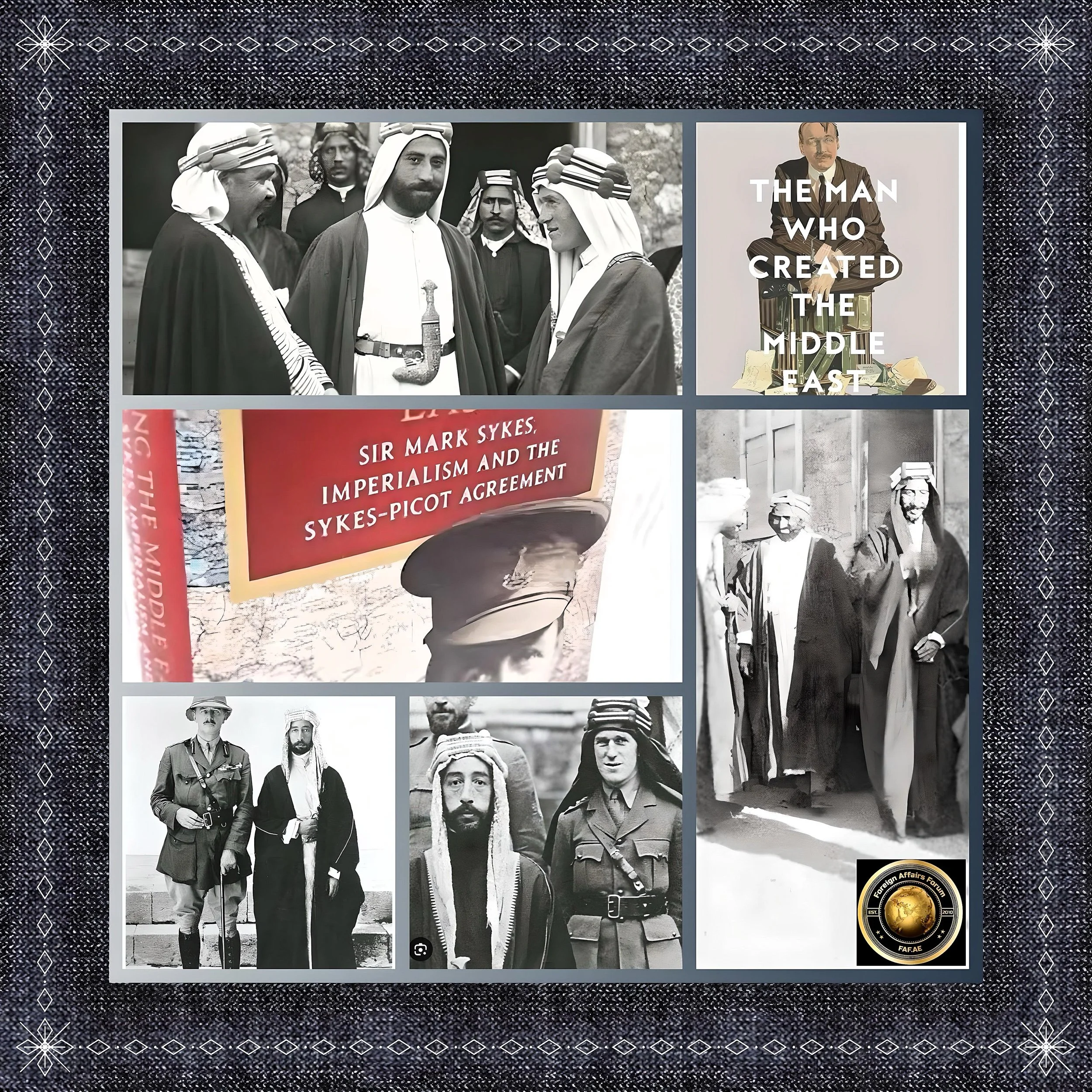

T.E. Lawrence emerged as the crucial liaison between British command and Arab forces, particularly Emir Faisal, Hussein’s son.

However, Anderson reveals the devastating duplicity at the heart of this alliance.

Simultaneously with their promises to the Arabs, Britain and France were secretly negotiating the Sykes-Picot Agreement in May 1916, which divided the Ottoman Empire’s Arab territories between British and French spheres of influence.

Under this arrangement, “the future independent Arab nation was to be relegated to the wastelands of the Arabian peninsula, while all the most politically and commercially valuable portions of the Arab world – greater Syria, Mesopotamia – would be carved into British and French imperial spheres”.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement: Imperial Cartography and Its Consequences

The Sykes-Picot Agreement represents one of history’s most consequential examples of colonial map-making without regard for local realities.

Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot, meeting in a London townhouse, “over the course of a day or two carved up the middle east between themselves”.

France received Syria and Lebanon, while Britain obtained Iraq, Palestine, and Transjordan.

Anderson demonstrates how this secret deal created “artificial nations” that would prove fundamentally unstable. The agreement “crossed tribal lines” and “divided up clans and sub-clans,” creating borders that bore no relation to ethnic, religious, or tribal realities.

As Anderson notes in contemporary interviews, “if you look at the Middle East today, there’s essentially five artificial nations that were created by Sykes-Picot, the most prominent ones being Iraq and Syria”.

Lawrence’s Moral Transformation and Act of Treason

Perhaps most remarkably, Anderson reveals how Lawrence, upon learning of the Sykes-Picot betrayal, committed what technically amounted to treason by informing Faisal of the secret agreement.

Lawrence’s motivation was clear: “Do not trust the promises my government has made to you… If what you want for the Arab people is, for an independent Arab nation, you have to fight and get on your own”.

This revelation fundamentally changed the dynamic of the revolt, as Lawrence advised the Arabs to secure territory through military action rather than rely on British promises.

The Paris Peace Conference: The Final Betrayal (1919)

The ultimate betrayal occurred at the Paris Peace Conference, where Lawrence attempted to advocate for Arab interests alongside Faisal.

However, the fate of the Middle East had already been decided in “a five minute conversation between Lloyd George, the British prime minister, and Georges Clemenceau, the French prime minister” in December 1918.

The division “was even worse than what had been outlined in the Sykes-Picot Agreement”.

Lawrence’s increasingly desperate efforts to secure justice for the Arabs led British officials to regard him as a “traitor,” and he was eventually “virtually officially banned from the paris peace conference and barred from communicating with faisal”.

The crushing irony was that as Lawrence was being marginalized for defending Arab interests, he was simultaneously becoming a household name in Britain through popular travelogues.

Central Narratives and Their Contemporary Resonance

Imperial Paternalism and the “White Man’s Burden”

Anderson identifies a crucial mindset that enabled these betrayals: European imperial paternalism that viewed independence not as genuine self-governance but as “a new round of the ‘white man’s burden,’ the tutoring – and, of course, the exploiting – of native peoples until they might sufficiently grasp the ways of modern civilization to stand on their own at some indeterminate point in the future”.

This paternalistic attitude justified breaking promises made to local allies while claiming moral superiority.

The Oil Imperative and Resource Geopolitics

Anderson reveals how oil considerations fundamentally shaped imperial decision-making.

William Yale, representing Standard Oil and later serving as the only American intelligence officer in the Middle East, exemplified how corporate interests intertwined with geopolitical strategy.

The British secured Mosul partly because of geological hints about oil deposits, establishing a pattern where resource control would override local political arrangements.

Arab Reactive Nationalism

One of Anderson’s most prescient observations concerns how these betrayals shaped Arab political consciousness.

He argues that “Arab society has tended to define itself less by what it aspires to become than by what it is opposed to: colonialism, Zionism, Western imperialism in its many forms”.

This reactive nationalism, born from the broken promises of World War I, created a political dynamic that would persist for generations.

Lessons for Contemporary Geopolitics

The Perils of External State-Building and Intervention

Anderson’s analysis provides crucial warnings about external attempts at state-building and regional transformation.

The artificial borders created in 1916-1922 demonstrate how “the imperial plotters of Europe” fundamentally misunderstood regional dynamics.

Contemporary analysts have directly connected these historical lessons to recent American interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan.

As one Heritage Foundation analysis notes, “America’s efforts at state building–be it in Haiti, Bosnia, Kosovo, Somalia, Afghanistan, or Iraq–have suffered from a tendency to reinvent the wheel”.

The book reveals how “most of the information being sent back was wrong” and “virtually no one was paying any attention” to intelligence from the region, highlighting persistent problems with Western intelligence and understanding of Middle Eastern societies.

This pattern of ignorance combined with ambitious intervention attempts has characterized Western policy from Lawrence’s era through contemporary conflicts.

The Enduring Consequences of Broken Promises

Anderson’s work demonstrates how diplomatic betrayals have multi-generational consequences.

The broken promises to the Arabs in 1919 created a “culture of opposition” and deep suspicion of Western intentions that continues to influence Middle Eastern politics.

This has profound implications for contemporary diplomacy, where historical memory of broken commitments affects the credibility of current negotiations and agreements.

The book shows how Lawrence himself recognized this dynamic, warning that “Arab, Christian and Moslems alike would fight in the matter to the last man against Jewish Dominion in Palestine” and that “if a Jewish state is to be created in Palestine, it will have to be done by force of arms and maintained by force of arms amid an overwhelmingly hostile population”.

These predictions proved tragically prescient, demonstrating how understanding historical patterns can illuminate persistent conflicts.

Imperial Overreach and Strategic Priorities

Anderson’s analysis reveals how imperial overreach led to strategic disasters.

The British and French “really thought that having won the war… this was now going to be their next tanganyika… their next morocco,” fundamentally misreading the post-war situation.

This imperial hubris led to commitments that proved unsustainable and created more problems than they solved.

This lesson has particular relevance for contemporary American foreign policy debates about “imperial overstretch” and the need for strategic prioritization.

Anderson’s work suggests that great powers must carefully consider the long-term sustainability of their commitments and avoid the temptation to remake entire regions according to their preferred models.

The ISIS Connection: History Repeating

Anderson’s analysis gains additional contemporary relevance through ISIS’s explicit rejection of Sykes-Picot borders.

ISIS propagandists declared their intention to “break” the borders established by Sykes-Picot, viewing the 1916 agreement as a “conspiracy” that needed to be overturned.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi explicitly vowed to “hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy”.

This demonstrates how the historical grievances documented by Anderson continue to motivate contemporary political movements.

The artificial nature of states like Iraq and Syria, created without regard for local realities, made them vulnerable to challenges from groups that could appeal to deeper religious or ethnic identities.

Resource Competition and Geopolitical Rivalry

The book’s examination of oil politics in the World War I era provides crucial context for understanding contemporary resource-based conflicts.

The pattern Anderson identifies—where resource considerations override political arrangements and local preferences—remains central to Middle Eastern geopolitics.

From the strategic control of oil pipelines to contemporary competition over energy resources, the dynamics Anderson describes in the 1916-1922 period continue to shape international relations.

Strategic Implications for Contemporary Policy

The Importance of Local Knowledge and Cultural Understanding

Anderson’s work emphasizes how Lawrence’s success stemmed partly from his genuine understanding of Arab culture and society, gained through years of archaeological work in the region.

Contemporary military analysts have noted how Lawrence’s “27 Articles” for dealing with Arab populations were rediscovered by American commanders during the Iraq War, though often misapplied due to lack of proper context.

The book suggests that successful engagement with the Middle East requires deep cultural knowledge and genuine respect for local agency, rather than the paternalistic approaches that characterized the World War I era and many subsequent interventions.

Understanding Historical Memory in Diplomacy

Anderson’s analysis demonstrates how historical events continue to shape contemporary political consciousness in the Middle East.

Any effective diplomatic engagement must account for this historical memory and the ways past betrayals continue to influence current attitudes toward Western powers.

The Limits of Military Solutions

The book reveals how military success—such as Lawrence’s campaigns against Ottoman forces—proves insufficient without political arrangements that address underlying grievances and aspirations.

Lawrence’s ultimate failure came not on the battlefield but in the diplomatic arena, where military achievements were undermined by political betrayals.

Conclusion

The Enduring Relevance of Historical Analysis

Scott Anderson’s “Lawrence in Arabia” provides essential insights for understanding contemporary Middle Eastern politics and the broader challenges of great power competition.

The book demonstrates how decisions made by a small group of individuals, often working without adequate oversight or understanding, can create dynamics that persist across generations.

The work’s analysis of imperial overreach, broken promises, and artificial state-creation offers crucial warnings for contemporary policymakers.

Anderson shows how the “folly of the past creates the anguish of the present,” establishing patterns of conflict and mistrust that continue to shape international relations.

The book’s documentation of how “the events that Lawrence took part in during the First World War succeeded in turning the Islamic world for ever against the west” provides sobering context for understanding persistent tensions between Western powers and Middle Eastern societies.

Most fundamentally, Anderson’s work demonstrates that effective international engagement requires genuine understanding of local cultures, respect for local agency, and recognition that external powers’ attempts to reshape entire regions according to their preferences often create more problems than they solve.

These lessons remain as relevant today as they were a century ago, making “Lawrence in Arabia” essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the complex dynamics that continue to shape Middle Eastern geopolitics and international relations more broadly.