The Original Sin: The Formation of the Arab State System Following the Ottoman Empire’s Collapse

Introduction

The carving up of the Middle East by European powers following World War I has often been described as the “original sin” that continues to haunt the region today.

When the Ottoman Empire collapsed after more than four centuries of rule, Britain and France seized the opportunity to reshape the region according to their imperial interests, creating artificial borders that disregarded local populations’ aspirations and ethnic realities.

Per FAF, Gulf.Inc, this reorganization of the Middle Eastern geopolitical landscape established a state system that many Arabs view as a fundamentally illegitimate colonial imposition that has fueled conflict, instability, and resentment for over a century.

The Ottoman Decline and European Ambitions

By the early 20th century, the Ottoman Empire was widely considered “the sick man of Europe,” experiencing a steady decline that had begun in the 18th century due to military defeats, internal revolts, and rampant corruption.

As World War I erupted, European powers saw the Ottoman decision to join the Central Powers as an opportunity to finally resolve the “Eastern question”: what would happen when the Ottoman Empire inevitably collapsed?

For Britain and France, the answer lay in creating new “zones of influence” to expand their colonial holdings and secure strategic and economic advantages.

The Arab provinces under Ottoman control had already been experiencing the stirrings of nationalism, with a growing intellectual movement in Syria and elsewhere advocating for greater Arab autonomy.

The completion of the Hejaz Railway in 1908 also heightened concerns among Arab leaders like Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, about increasing Ottoman control in traditionally autonomous regions.

These conditions set the stage for opportunistic alliances between European powers and Arab leaders that would ultimately reshape the region.

Contradictory Promises and Secret Agreements

Between 1915 and 1917, Britain made a series of contradictory promises to different parties regarding the future of Ottoman territories. These competing commitments would sow confusion and resentment that continues to this day.

The McMahon-Hussein Correspondence

In July 1915, a series of letters began between Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, and Sir Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner to Egypt.

Over the next eight months, ten letters were exchanged, and the British government effectively agreed to recognize Arab independence in exchange for Hussein launching a revolt against the Ottoman Empire.

Hussein’s first letter on July 14, 1915, requested British recognition of Arab independence in territories “bounded on the North by Mersina and Adana up to 37 degrees of latitude… on the east by the borders of Persia up to the Gulf of Basra; on the South by the Indian Ocean… on the west by the Red Sea, the Mediterranean Sea up to Mersina”.

McMahon’s reply in October 1915 acknowledged Arab independence but with significant exclusions: “The two districts of Mersina and Alexandretta and portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab, and should be excluded from the limits demanded.”

These exclusions, particularly regarding Palestine, would later become a significant point of contention, with Arabs and British offering conflicting interpretations of whether Palestine was meant to be included in the promised Arab state.

The correspondence, viewed by Arabs “as a formal agreement between themselves and the United Kingdom,” became the basis for Arab participation in the revolt against the Ottomans. However, the British had other plans that directly contradicted these promises.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement

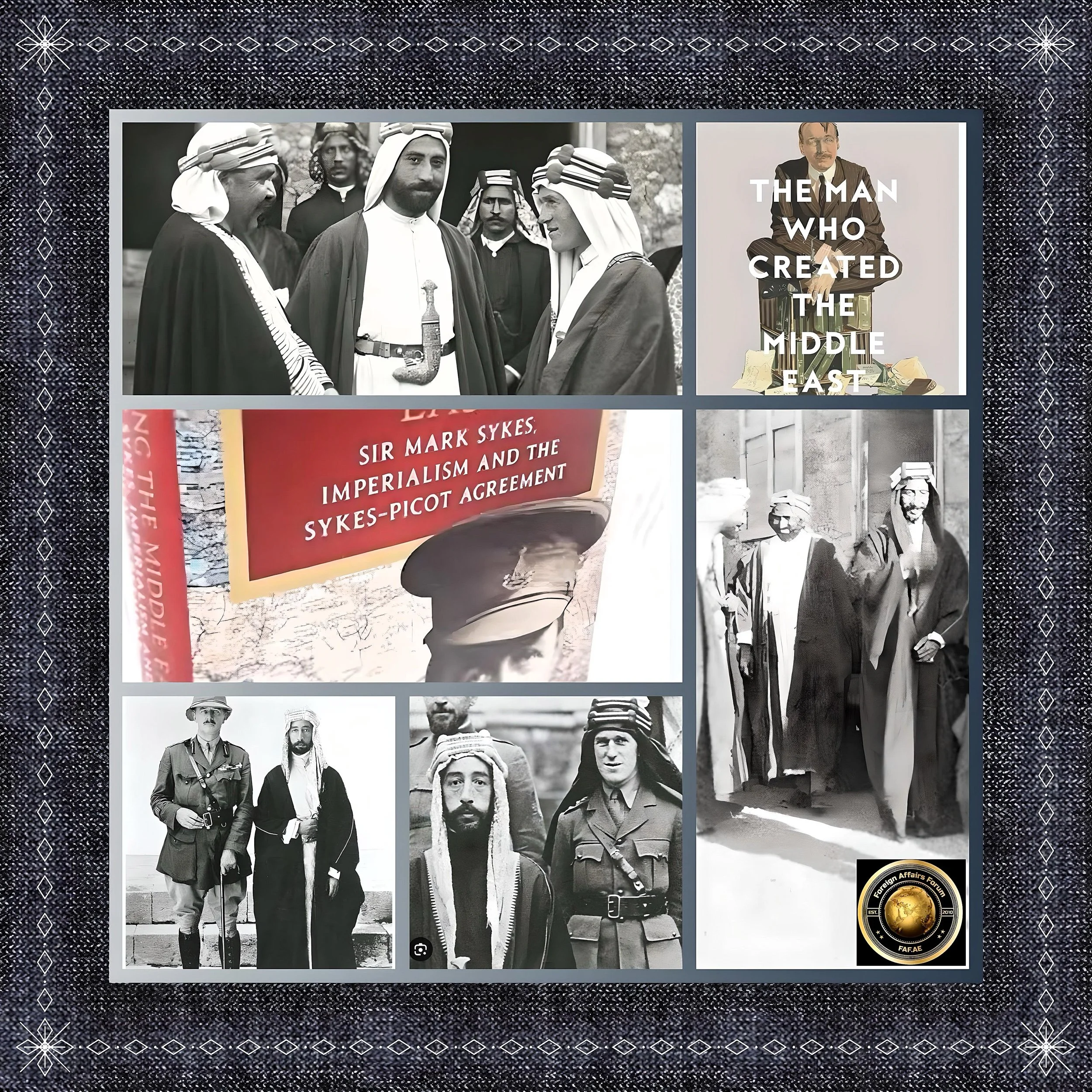

Even as McMahon corresponded with Hussein, Britain secretly negotiated with France to divide the territories promised to the Arabs.

Between November 1915 and March 1916, British diplomat Sir Mark Sykes and French counterpart François Georges-Picot drafted what became known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement, signed in May 1916.

This secret treaty envisioned a post-war Middle East divided into British and French spheres of influence, with:

France obtained control of “the blue area” covering modern-day Syria, Lebanon, northern Iraq, and southeastern Turkey, including Kurdistan

Britain received “the red area” encompassing Jordan, southern Iraq, and Haifa in Israel

Palestine (excluding Haifa and Acre) is becoming subject to “international administration.”

The agreement fundamentally contradicted Hussein's promises, though British officials like McMahon may have recognized this duplicity.

In a private letter from December 1915, McMahon revealed his true thoughts: “I do not take the idea of a future strong united independent Arab State… too seriously… What we have to arrive at now is to tempt the Arab people into the right path, detach them from the enemy, and bring them onto our side. This on our part is at present largely a matter of words…”

When the Bolsheviks revealed the agreement in November 1917 after the Russian Revolution, “the British were embarrassed, the Arabs dismayed, and the Turks delighted.”

The revelation exposed Britain’s duplicity and planted deep seeds of distrust toward Western powers among Arabs.

The Balfour Declaration

Adding a third layer of contradictory promises, in November 1917, British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour issued a declaration supporting “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” while promising that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.”

This statement directly conflicted with earlier assurances to Arabs regarding self-determination in territories that included Palestine.

The Arab Revolt and Emergent Arab Nationalism

Despite Britain’s secret dealings with France, the Arab Revolt began in June 1916 when Hussein bin Ali’s forces moved against Ottoman troops.

Led by Hussein’s son Faisal and supported by British officers like T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”), Arab forces participated in key operations, including capturing Aqaba and disrupting the Hejaz railway.

The revolt represented the first organized manifestation of Arab nationalism, bringing together diverse Arab groups with the goal of independence from Ottoman rule.

The fighters believed they were fighting to create a unified Arab kingdom, as promised in the McMahon-Hussein correspondence.

However, historian Peter Wien noted that recent scholarship suggests the revolt was “less about true popular aspirations and more the result of Sharifian dynastic ambitions converging with British strategic interests.”

Nevertheless, the revolt became what Wien called “the founding myth of Arab nationalism” and was extensively used to legitimize Faisal’s later claim to rule in Syria.

The uprising succeeded militarily, contributing to the Ottoman Empire’s defeat and capitulation on October 31, 1918, but the political outcomes would deeply disappoint Arab nationalists.

Post-War Conferences and the Mandate System

With the war’s end, European powers moved quickly to formalize their control over former Ottoman territories, creating a system prioritizing their imperial interests while giving only lip service to Arab aspirations for independence.

The Paris Peace Conference and San Remo

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Faisal pushed for Arab independence, but his position was undermined by the secret agreements already in place.

The Allied Powers, ignoring Arab claims to self-determination, proceeded to divide the region according to their interests.

The San Remo Conference in April 1920 confirmed the mandate system, allocating “Class A” League of Nations mandates for the administration of three Ottoman territories: Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia.

Britain, France, Italy, and Japan attended the conference, with the United States acting as a neutral observer but notably excluding any Arab representation.

The mandates were ostensibly based on Article 22 of the League of Nations Covenant, which characterized them as “administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory until they can stand alone.”

However, the mandates functioned as thinly veiled colonialism, transferring control from the defeated Ottoman Empire to the victorious Allied powers.

The Creation of New States

Following the San Remo Conference, Britain and France quickly established political entities under their control while suppressing indigenous movements for true independence.

Kingdom of Syria and French Mandate

After British forces withdrew from Damascus in November 1919, Faisal declared himself king of the Arab Kingdom of Syria on March 8, 1920.

This short-lived kingdom represented the first attempt to establish an independent Arab state after the Ottoman collapse.

However, France had already been allocated this territory under the Sykes-Picot Agreement and quickly moved to assert control.

In July 1920, French forces defeated Yusuf al-‘Azma’s Syrian army at the Battle of Maysalun, entered Damascus, and forced Faisal into exile on July 25, 1920.

General Henri Gouraud, the French high commissioner, then divided Syria into several smaller states, implementing a “divide and rule” strategy that made the territory easier to control.

The French mandate would last until 1943, eventually resulting in the independent states of Syria and Lebanon.

Iraq Under British Control

Britain faced fierce resistance to its rule in Mesopotamia, with the 1920 Iraqi Revolt forcing a reconsideration of direct colonial administration. Instead, Britain established the Kingdom of Iraq under the British administration, importing Faisal (expelled from Syria) as king in August 1921.

The British hoped that “Faisal, as a direct descendant of the Prophet, would be granted sufficient legitimacy by the Arabs, but as an outsider in Iraq, he was also weak enough to remain compliant to British interests.”

This arrangement was formalized through the 1922 Anglo-Iraqi Treaty and remained under British oversight until nominal independence in 1932.

Notably, the referendum that installed Faisal showed significant dissent in Kirkuk, “where the Turks favored a ruler to be chosen from the Ottoman dynasty, and the Kurds asked for a Kurdish administration.” This demonstrated how the new borders failed to account for local ethnic identities and aspirations.

Palestine and Transjordan

The British Mandate for Palestine, which became effective in September 1923, included the obligation to implement the Balfour Declaration’s promise of “a national home for the Jewish people” while protecting the rights of the Palestinian Arab majority.

This dual and contradictory commitment proved impossible to fulfill.

As the British Foreign Secretary Lord Passfield acknowledged in 1930: “In the Balfour Declaration, there is no suggestion that the Jews should be accorded a special or favored position in Palestine as compared with the Arab inhabitants of the country, or that the claims of Palestinians to enjoy self-government… should be curtailed to facilitate the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people”.

The British eventually separated Transjordan (modern Jordan) from Palestine proper, installing Abdullah, another of Hussein’s sons, as its ruler in April 1921.

This division represented another arbitrary border drawn by colonial powers rather than reflecting local realities.

The Legacy of the “Original Sin”

The arbitrary division of the former Ottoman territories has had profound and lasting consequences for the Middle East, many of which continue to shape regional politics today.

Betrayal and Resentment

For Arabs, the post-WWI settlement represents a profound betrayal. Having fought alongside the Allies against the Ottomans based on promises of independence, they found themselves subject to European colonial rule.

As George Antonius, an early scholar of Arab nationalism, noted, the Arab Revolt was viewed by Arabs as “a revolutionary struggle for emancipation inspired by the process of the Arabs awakening to their unique identity,” making the imposition of European mandates all the more bitter.

This betrayal was compounded by the revelation of the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which Arabs saw as “the failure to keep a British promise in the McMahon–Hussein correspondence with Hussein bin Ali.”

A century later, Arab media still marks the anniversary of Sykes-Picot with “bitterness and regret,” describing it as an “ominous” deal that “divided the Arab nation.”

Artificial Borders and Ongoing Conflict

The borders drawn by European powers paid little attention to ethnic, religious, or tribal realities on the ground.

As described in a 2016 article, the Sykes-Picot Agreement “created artificial borders, drawn without regard for the region’s complex ethnic and sectarian makeup,” which have been “a source of long-standing tension.”

Lawrence of Arabia recognized this problem in January 1916, writing that the states set up by the British would be “harmless to ourselves” because “The Arabs are even less stable than the Turks.

If properly handled, they would remain in a political mosaic, a tissue of small jealous principalities incapable of cohesion”.

This cynical assessment reveals the colonial mindset, prioritizing imperial control over stable and viable states.

The results of these artificial divisions include ongoing conflicts between and within states, border disputes, and the suppression of minority groups whose identities and territories were split by colonial-era boundaries.

The Kurdish people, for instance, were promised autonomy under the Treaty of Sèvres but instead found themselves divided between Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran-a situation that continues to fuel conflict today.

Rise of Arab Nationalism as Response

Perhaps the most significant legacy of this “original sin” has been the rise of Arab nationalism as a response to colonial division. As journalist Peter Wien noted, the Arab Revolt became “the founding myth of Arab nationalism” despite its origins in dynastic ambition rather than popular sentiment.

By the mid-20th century, Arab nationalism had evolved into “the overwhelmingly dominant ideological force in the Arab world,” championed by leaders like Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser.

The movement’s primary goals included “ridding the Arab world of influence from the Western world, and the removal of those Arab governments that are dependent upon Western hegemony,” a direct response to the colonial legacy of the post-WWI settlement.

Arab nationalists “centralized themselves around the newfound Palestine cause, promoting the view that Zionism posed an existential threat to the territorial integrity and political status quo of the entire region” and linking this threat directly to “Western imperialism due to the Balfour Declaration.”

This perspective continues to shape regional politics today.

Conclusion

An Enduring Legacy

The formation of the modern Arab state system following the Ottoman Empire’s collapse remains one of the most consequential episodes in Middle Eastern history.

The secret agreements, broken promises, and imperial ambitions that shaped this process created states with questionable legitimacy in the eyes of their populations, “original sin,” whose consequences continue to unfold.

As we witness ongoing conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Palestine, it is impossible to ignore the shadow cast by decisions made in London, Paris, and San Remo over a century ago.

The borders drawn by Sykes and Picot, initially seen as temporary administrative conveniences, have hardened into contested state boundaries that continue to divide peoples and fuel conflicts.

While some Arab thinkers now pragmatically view the Sykes-Picot borders as a “necessary evil” that prevents further fragmentation, the fundamental issues of legitimacy and self-determination remain unresolved.

The modern Middle East continues to grapple with this colonial legacy, seeking paths toward stability and sovereignty that acknowledge rather than ignore the aspirations of the region’s diverse peoples.

The “original sin” of European colonial partition has proven remarkably durable, but its consequences remain deeply contested.

This is a testament to the enduring importance of genuine self-determination and the dangers of imposing geopolitical arrangements disregarding local realities and aspirations.