Iran on the Precipice: Economic Collapse and the Islamic Republic’s Race Against History

Executive Summary

Prologue of Collapse: Executive Summary — When Currency Dies, and Legitimacy Follows

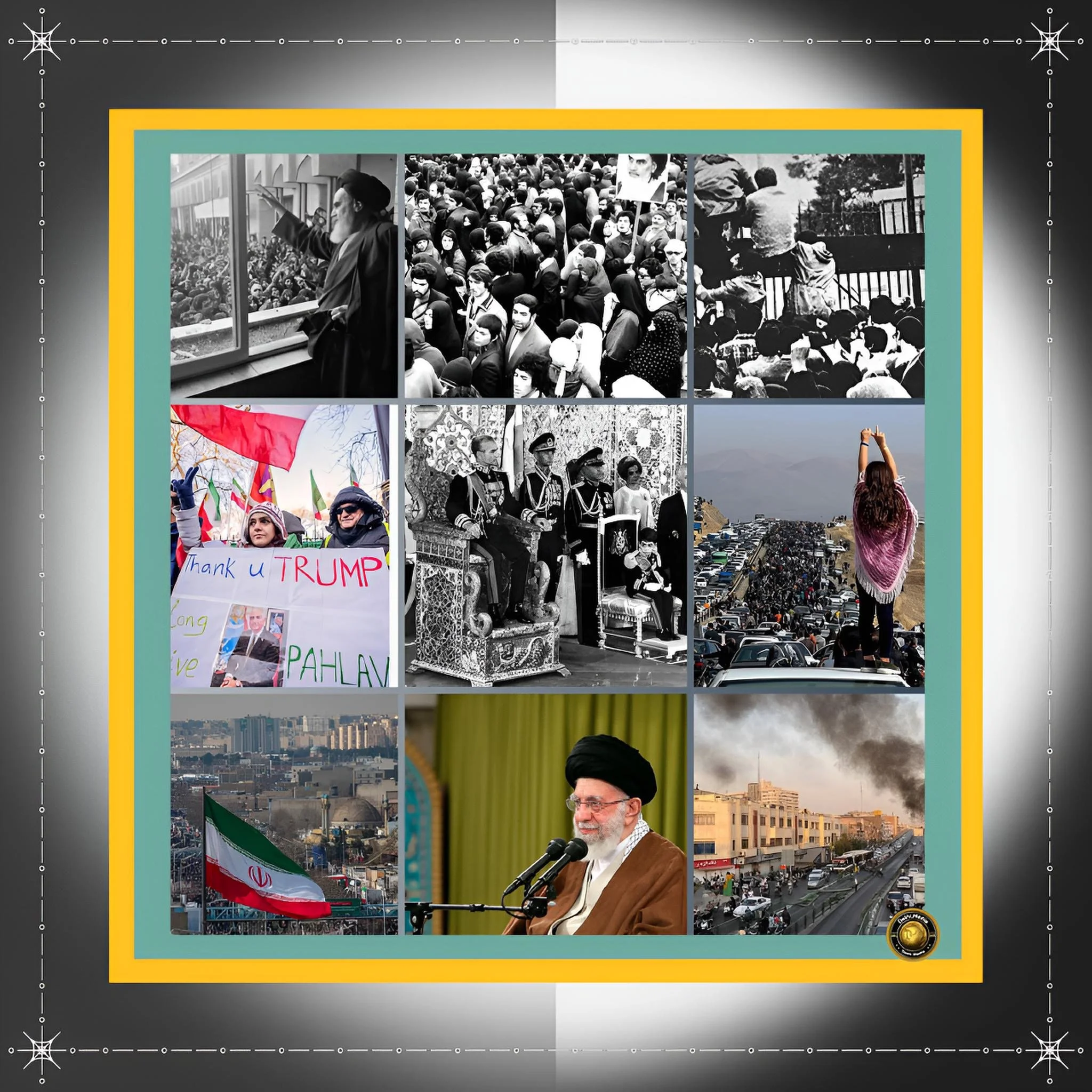

The Islamic Republic of Iran faces its most consequential internal challenge since the 2022–2023 Women, Life, Freedom protests following the death of Mahsa Amini. Beginning on December 28, 2025, widespread anti-government demonstrations erupted across all 31 provinces and in 348 documented locations spanning 111 cities, encompassing 45 universities and drawing participation from merchants, students, workers, and ethnic minorities.

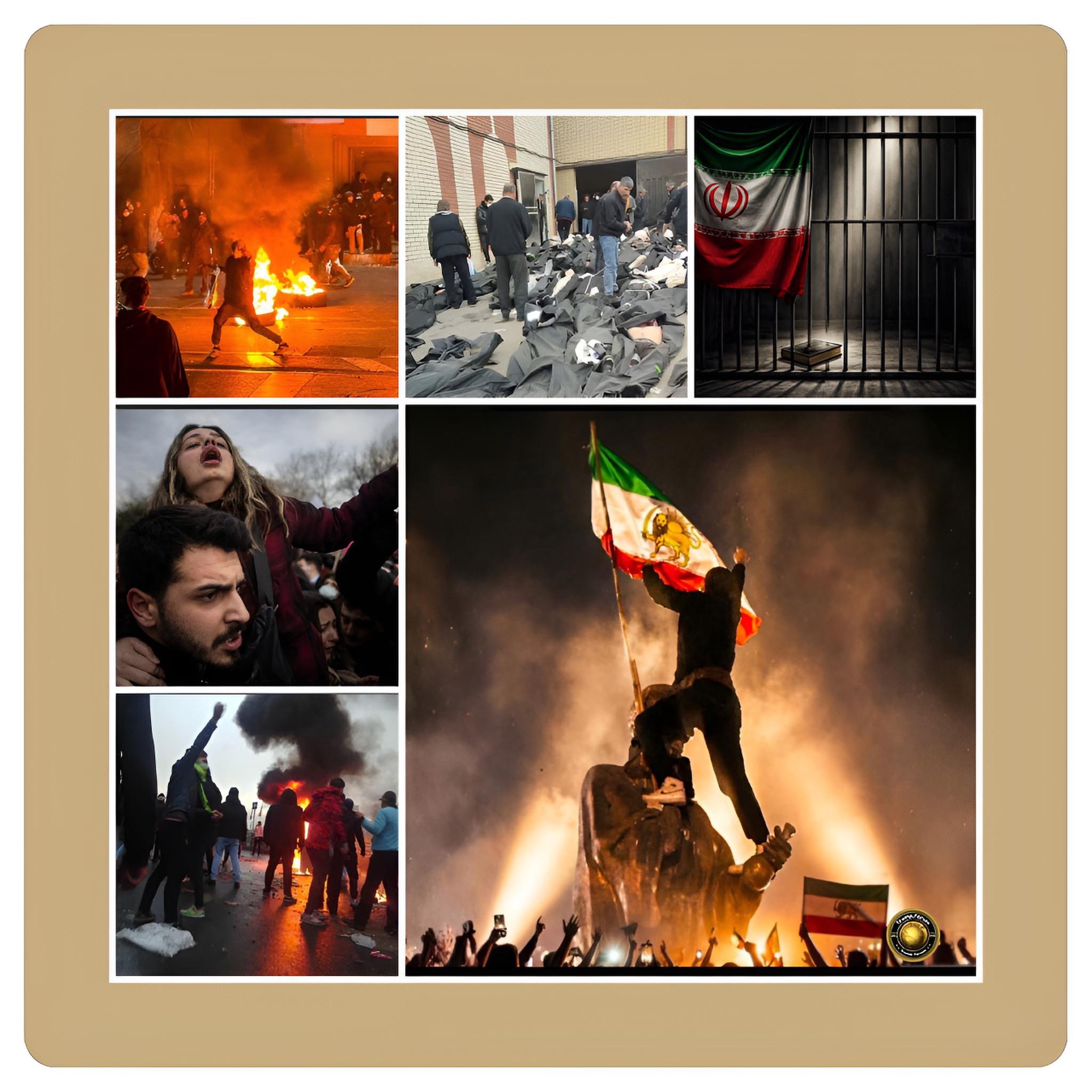

As of January 8, 2026—the twelfth day of sustained unrest—the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) has presided over a escalating crackdown that has resulted in at least 38 documented deaths (29 adult protesters, five minors, and four security personnel), more than 2,217 arrests (including 165 minors), and 51 confirmed injuries from live ammunition and pellet fire.

The immediate catalyst was the catastrophic collapse of the Iranian rial to unprecedented lows of 1.5 million to the US dollar, triggering hourly price increases in essential goods and exposing the structural bankruptcy of Iran's economy.

What began as merchants' grievances over currency destabilization has evolved into a fundamental rejection of the Islamic Republic itself, with protesters explicitly chanting demands for the overthrow of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and invoking pre-revolutionary monarchist symbolism.

The regime, acknowledging that domestic security forces may be inadequate or insufficiently motivated to suppress nationwide unrest, has imported approximately 800 Iraqi Shia militia fighters to augment its coercive apparatus.

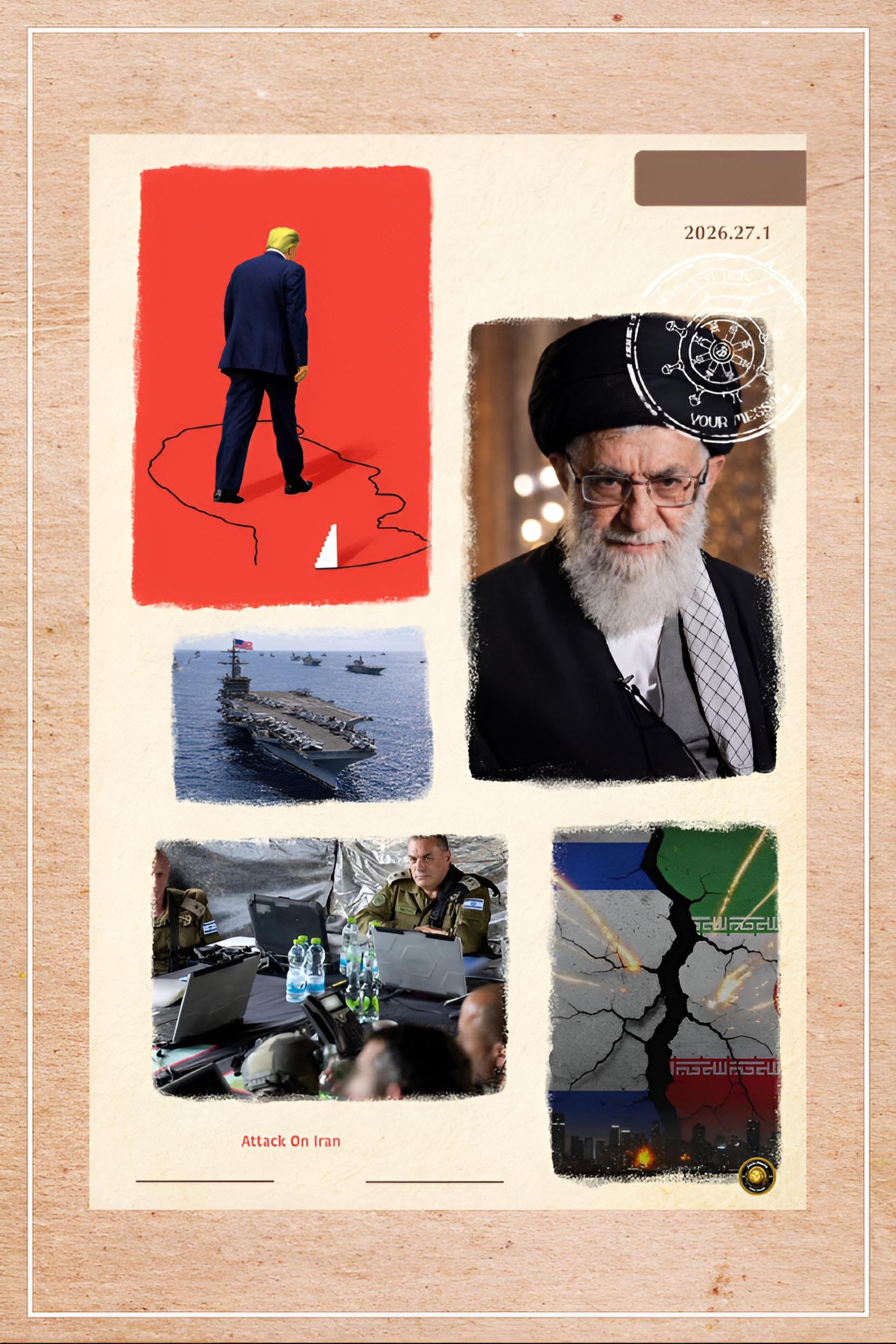

Meanwhile, foreign powers—particularly the United States and Israel—have issued rhetorical support for demonstrators, allegations of interference that Iran's government has weaponised to characterise the uprising as a foreign-orchestrated conspiracy rather than an organic expression of economic desperation and political exhaustion.

The question confronting the international community and regional analysts is not whether these protests will intensify or fade within days, but whether structural economic collapse and the regime's reliance on imported mercenary forces signal the beginning of a cascade that could fundamentally alter the Islamic Republic's trajectory.

Introduction

When Federal Authority Collides with Democratic Institutions: The Renee Nicole Good Tragedy and Questions of Constitutional Order

In the final days of December 2025, the Islamic Republic confronted a crisis that its leadership could neither easily dismiss as the machinations of foreign adversaries nor resolve through a mix of limited economic concessions and overwhelming security force deployments that had historically characterised its response to domestic unrest.

The Iranian rial, which had already lost approximately 20,000 percent of its value since the 1979 revolution, descended to new historic lows. For ordinary Iranians—a population of 92 million already grappling with food inflation exceeding 72 percent year-on-year and official inflation figures of 42.2 percent—the currency's freefall represented a final crossing of a threshold from economic hardship into psychological disintegration.

The purchasing power that had enabled Iranians to afford cooking oil, meat, and medicine in December 2024 had evaporated. Shopkeepers in Tehran's Grand Bazaar, merchants in provincial markets, and students on university campuses recognised the imminent collapse of their livelihoods and futures.

They took to the streets, and in doing so, transformed what might have been another ephemeral economic grievance into the beginning of the most geographically expansive and politically ambitious challenge to the Islamic Republic since the upheaval following Mahsa Amini's death in 2022.

This scholarly examination analyses the genesis, progression, governmental response, and prospective trajectory of Iran's December 2025–January 2026 protests through multiple analytical lenses: the structural economic crisis underpinning unrest, the IRGC's tactical evolution from restraint to lethal force, allegations of foreign involvement and the evidence supporting or refuting such claims, and the historical precedent of previous Iranian protest cycles.

The analysis demonstrates that while external rhetorical support from Washington and Jerusalem has provided psychological encouragement to protesters, the primary drivers of this uprising are domestic and structural, rooted in decades of economic mismanagement, ideological prioritisation of proxy warfare over citizen welfare, and the compounding failures of successive Iranian administrations to stabilise the currency, contain inflation, and rebuild foreign investor confidence.

Simultaneously, the evidence indicates that the protests have transcended their economic origins and now constitute an explicit rejection of the Islamic Republic's fundamental legitimacy—a shift visible in slogans invoking the restoration of the monarchy, the toppling of statues depicting the regime's martyrs, and the explicit chanting of "Death to Khamenei." Whether such a transformation will culminate in the regime's collapse, a new cycle of suppression followed by quiescence, or sustained insurgent pressure over months remains uncertain.

What is clear is that the Islamic Republic's reliance on imported foreign militias, the IRGC's deployment of lethal force against civilians, including minors, and the government's strategic framing of authentic domestic discontent as a foreign-orchestrated conspiracy all signal a regime straining at the limits of its coercive capacity and ideological coherence.

The Pattern Broken: Historical Context and Precedent — Why 2025 Is Different From 1999, 2019, and 2022

To comprehend the significance of the current unrest, one must situate it within Iran's protest landscape since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The Islamic Republic has faced five major waves of nationwide or regionally significant unrest, each met with a combination of security force suppression and, in some cases, limited policy concessions.

The July 1999 student protests, triggered by the closure of the reformist newspaper Salam and a paramilitary raid on a student dormitory, spread to multiple cities before being suppressed through the detention of over 1,200 individuals and at least five documented deaths.

The subsequent two decades witnessed protests against fuel prices, water scarcity, unemployment, and university fees—grievances that were episodic rather than sustained, suppressed with varying degrees of violence. They ultimately managed through the regime's dual strategy of cosmetic institutional adjustments and the deployment of security forces.

The November 2019 fuel price protests constituted a turning point in scale and lethality. When the government announced sharp increases in fuel prices, demonstrations erupted across the country and were met with live ammunition; security forces killed between 304 and 1,500 individuals, depending on the source, deployed a nationwide internet blackout lasting nearly a week, and arrested thousands.

The regime survived this challenge through sheer coercive power, but at the cost of deepening Iranians' perception that dialogue and reform were illusory and that the Islamic Republic was fundamentally committed to protecting its revenue streams over citizen welfare.

The Woman, Life, Freedom protests of 2022–2023, ignited by the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini while in police custody for allegedly wearing her hijab improperly, represented a different species of unrest. Sustained over months with recurring waves of demonstrations, these protests transcended gender rights and economic grievance to become an explicit rejection of the Islamic Republic's claim to governance.

Analysts at the time noted that the regime's response—violence alongside cosmetic relaxation of dress code enforcement—did not address the underlying distrust in state institutions.

Crucially, the 2022–2023 protests demonstrated that even when the government offered policy concessions (reducing enforcement of mandatory hijab rules), the demonstrations did not dissipate; the boundary between specific demands and systemic critique had become permanently blurred.

The December 2025–January 2026 protests differ from their predecessors in scale, the speed of their spread, and their ideological character. Unlike the 2019 fuel protests, which were geographically concentrated in petroleum-producing regions and urban centres, the current unrest has spread across all 31 provinces within 11 days.

Unlike the 2022 Amini protests, which took two weeks to achieve nationwide visibility, the December 2025 demonstrations achieved provincial saturation within three days. And critically, unlike all previous protest cycles where demands centred on specific grievances susceptible to limited policy adjustment, the current slogans—"Death to Khamenei," invocations of monarchy, the toppling of revolutionary martyrs' statues—constitute explicit demands for regime change.

Historical precedent thus suggests that previous suppression strategies, however successful in the short term, have failed to arrest the compound growth of anti-regime sentiment over decades. The current unrest arrives at a moment when such accumulated discontent coincides with objective economic collapse.

The Arithmetic of Desperation: Economic Catastrophe as Structural Catalyst — How Twenty Thousand Percent Devaluation Destroys a State

The immediate trigger for the December 28, 2025, protests was the rial's descent to 1.45 million to the US dollar, surpassing previous historic lows and representing a decline of approximately 40 percent in value since the June 2025 conflict between Iran and Israel. However, this singular currency shock occurred within a context of multi-year economic deterioration that had strained household purchasing power and eroded public confidence in the competence of state institutions.

The roots of Iran's current economic crisis extend across multiple policy domains and external pressures. Internationally imposed sanctions, intensified by the September 2025 activation of the UN's "snapback" mechanism in response to Iran's ballistic missile activities, froze Iranian assets abroad, halted arms transactions, and devastated Iran's ability to monetise its oil exports.

The June 2025 conflict with Israel and the United States, during which American forces struck Iranian nuclear facilities, inflicted psychological damage on investor confidence and further degraded Iran's regional economic position by contributing to the fall of the Assad regime. This long-standing ally had served as a crucial node in Iran's regional logistics and influence networks.

Domestically, successive administrations' prioritisation of expenditure on proxy militias in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, combined with endemic corruption that has redirected state resources toward regime-connected oligarchs, left Iran with a massive structural budget deficit estimated at between 400 and 1,800 trillion tomans.

These factors converged in late 2025, triggering a liquidity crisis and currency panic. Official inflation stood at 42.2 percent in December 2025. Still, the consumer experience was far more severe: food prices had surged 72 percent year-on-year, health and medical goods rose 50 percent, and the government's decision to reduce subsidised access to foreign exchange for essential imports created artificial scarcities that further accelerated price increases.

Middle-class families discovered that their savings, denominated in rials, had evaporated in purchasing power. Small shopkeepers dependent on imports found themselves unable to set prices with any certainty as the rial's value fluctuated hourly. Workers' wages, frozen or rising nominally while inflation accelerated in double and triple digits, ceased to provide subsistence. Between 27 and 50 percent of Iranians were estimated to be living below the poverty line—a catastrophic increase from 2022, when this percentage was substantially lower.

The government's response, undertaken under pressure and acknowledged by analysts as inadequate, consisted of appointing a new Central Bank governor, announcing a monthly food subsidy of approximately seven dollars per household, and issuing threats against speculators.

These measures addressed neither the underlying currency instability nor the fiscal crisis driving it. Economic analysts noted that without addressing the massive budget deficit and the rapid expansion of the money supply—which the government had engaged in to cover expenditures it could not finance through taxation or external borrowing—any intervention would be superficial.

One former Central Bank deputy warned that defending the rial through foreign-exchange interventions would drain reserves needed for essential imports, triggering a cascading crisis.

In essence, the Iranian government faced a trilemma with no satisfactory solution: stabilise the currency through reserve depletion at the cost of importing necessities; allow currency depreciation and accept hyperinflation; or undertake the politically and ideologically costly restructuring of expenditure by dramatically reducing spending on regional proxy militias and conventional military capabilities.

The December 28 rupture in the currency market thus represented not a discrete shock but the breaking point of accumulated economic failure.

For merchants, students, workers, and pensioners, it signalled that the Islamic Republic's leadership was fundamentally incompetent or, more damningly, prioritised other objectives over the economic survival of ordinary Iranians. This recognition transformed the protests from an economic grievance into a political crisis.

From Markets to Martyrs: Protest Dynamics: Genesis, Geographic Expansion, and Ideological Evolution — The Morphing of Merchant Grievance Into Revolutionary Demand

The first demonstrations emerged on December 28, 2025, among Tehran's merchants and shopkeepers, particularly those dealing in electronic goods and currency exchange.

These initial gatherings at commercial centres such as Alaeddin Shopping Centre and Charsou Malls were notably peaceful; security forces did not intervene, and participants focused on specific demands: stabilising exchange rates, preventing bankruptcy due to market volatility, and government recognition of merchants' plight.

However, even in these incipient stages, observers noted that the boundary between economic grievance and political criticism had begun to blur. Footage distributed on social media showed merchants chanting not only for currency stability but also for "freedom" and, in some locales, implicitly criticizing government management.

The expansion over subsequent days followed a pattern of cascade diffusion. By December 29, protests had spread to multiple districts in Tehran and to other major urban centres: Isfahan, Shiraz, Mashhad, Kermanshah, Hamadan, and smaller towns. Critically, the Grand Bazaar—a historically potent site of mobilisation whose merchants' strike had played a decisive role in the 1979 revolution—became the symbolic and physical centre of the unrest.

Security forces responded with tear gas, but the symbolic resonance of the bazaar's strike ensured that media coverage, diaspora networks, and international observers recognised the current moment as comparable in potential to the revolutionary period itself.

The geographic expansion accelerated with extraordinary velocity. By the sixth day of protests (January 3, 2026), unrest had reached 113 locations across 46 cities in 22 provinces. By January 7, the twelfth day, protests had been documented in 348 sites spanning 111 cities across all 31 Iranian provinces. Universities became recruitment nodes; by January 7, 45 universities had witnessed student-led demonstrations.

Critically, the western provinces—Ilam, Kermanshah, Lorestan, and Hamedan—which comprise regions with significant Kurdish, Lur, and other ethnic minority populations, emerged as the sites of both the most substantial protests and the deadliest government crackdowns.

The IRGC's particular brutality in these regions suggests both the depth of anti-regime sentiment among minorities and the security establishment's perception of ethnic minority regions as more susceptible to foreign infiltration or separatist ideology.

Even more significant than the geographic expansion was the ideological transformation of protest slogans and demands. What had begun as merchants' calls for exchange rate stability evolved, within days, into explicit demands for regime change.

The slogan "Death to Khamenei"—directed at Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei personally—became ubiquitous across multiple cities, signalling that protesters were no longer seeking policy reforms within the Islamic Republic but rather the regime's overthrow. More strikingly, and perhaps most threatening to the regime's revolutionary legitimacy, protesters began invoking monarchist sentiments: "Long live the Shah," "Pahlavi will return," and "This is the final battle, Pahlavi will return."

The Lion and Sun flag—the national emblem of the pre-revolutionary monarchy—appeared in demonstrations, explicitly symbolising rejection of the Islamic Republic's legitimacy and nostalgia for the ancien régime despite its well-documented authoritarianism and repression.

Equally significant was the slogans' implicit critique of the regime's foreign policy priorities. The chant "Neither Gaza nor Lebanon, My Life for Iran" articulated a complaint that the Islamic Republic had subordinated domestic welfare to military support for Palestinian militant organisations and the Lebanese Hezbollah.

This represented not merely economic grievance but ideological rejection of the Islamic Republic's foundational claim that martyrdom in regional conflicts served a higher purpose. Simultaneously, in several cities, demonstrators toppled or defaced statues of Qassem Soleimani, the IRGC general killed in a 2020 US airstrike and venerated by the regime as a central martyr-figure.

The desecration of Soleimani's monuments constituted an assault on one of the Islamic Republic's core symbols of legitimacy and regional power projection.

By the seventh and eighth days of protests, merchants' strikes had expanded beyond individual shops to coordinated closures in bazaars across multiple cities. Simultaneously, workers in various sectors—particularly in energy production and transportation—began joining the demonstrations, signalling that the unrest had transcended merchant grievances and was starting to draw on working-class constituencies.

Teachers, artists, and intellectuals issued public statements supporting the protests and condemning security force violence. Civil society organisations, including the Free Workers' Union of Iran and the Iranian Writers' Association, formally endorsed the demonstrations and called for the end of Islamic Republic rule.

The political character of the movement had crystallised: it was no longer a merchants' economic complaint but a multi-sectoral challenge to the regime's legitimacy.

The Machinery of Suppression: The IRGC's Tactical Evolution and Escalating Brutality — From Tear Gas to Hospital Raids to Lethal Force

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps' response to the protests evolved in distinct phases, each more brutal than the preceding one. This escalation occurred not gradually or as a natural response to escalating protester violence, but rather in direct consequence of explicit directives from Supreme Leader Khamenei and senior regime figures.

During the first two days of protests (December 28–29), the IRGC and law enforcement forces exercised relative restraint. Tear gas was deployed in Tehran, and there were isolated confrontations, but no documented lethal force was applied.

This restraint may have reflected initial miscalculation by regime planners who believed the protests would dissipate as previous unrest had, or it may have indicated internal debate within the security apparatus regarding the appropriate response intensity. However, on January 3, 2026—the sixth day of protests—Supreme Leader Khamenei issued a speech in which he explicitly characterised protesters as "rioters" rather than legitimate demonstrators and declared that such rioters "must be put in their place."

This rhetorical shift from acknowledging "the constitutional right of peaceful protest" (as President Masoud Pezeshkian had stated) to explicit repressive rhetoric signalled a change in regime direction.

Following Khamenei's January 3 speech, the IRGC's tactics transformed dramatically. From January 3 onwards, documented instances of live ammunition fire by security forces multiplied exponentially. Witnesses, human rights organisations, and family accounts recorded that IRGC and plainclothes security personnel shot protesters in the head, chest, and abdomen with military-grade weapons, including Kalashnikov rifles and handguns.

The Malekshahi County region in Ilam Province became a symbol of the security forces' brutality; on January 3 alone, IRGC personnel fired military-grade weapons at demonstrators, killing at least four civilians and injuring approximately 40 others.

A 22-year-old woman, Saghar Etemadi, was shot in the face by security forces and died two days later in the hospital. A retired brigadier-general, Latif Karimi, was shot dead by IRGC personnel while standing among protesters, having reportedly attempted to prevent security forces from firing on civilians; regime media falsely claimed he was a casualty inflicted by protesters before family members and eyewitnesses contradicted these accounts.

Beyond direct lethal force, the IRGC coordinated a campaign of institutional violence that extended to hospitals and medical personnel.

On January 5, security forces stormed the Imam Khomeini Hospital in Ilam Province, where injured protesters were receiving treatment. Witnesses reported that security forces fired tear gas inside hospital buildings and grounds, attempted to arrest wounded patients, and created a chaotic environment that forced medical staff to choose between providing care and preventing the arrest of their patients.

This raid on a hospital—a violation of international humanitarian law—provoked condemnation even from some regime-aligned figures and generated symbolic images of state violence that circulated globally.

Simultaneously, the IRGC oversaw a coordinated campaign of forced confessions. By January 7, approximately 40 arrested protesters had been compelled to provide televised "confessions" acknowledging various charges or expressing remorse.

These confessions, broadcast on state media, were widely recognised as coerced and served primarily to demoralise the broader protest movement and to create a false narrative that the regime retained control over the narrative environment.

The regime also engaged in systematic pressure on the families of deceased protesters. In several cases, the IRGC and affiliated officials conditioned families' access to their relatives' bodies on the families making televised statements falsely claiming that the deceased had been members of the paramilitary Basij militia.

In the case of Amirhesam Khodayarifard, a protester killed by a plainclothes IRGC agent on December 31 with a shot to the head, the regime refused to release his body until his family agreed to claim he was a Basij member—a claim contradicted by eyewitnesses, video evidence, and Khodayarifard's father, who publicly stated that his son was not affiliated with any security force.

By January 7, the IRGC's crackdown had resulted in documented deaths of 38 individuals (29 adult protesters, five minors, and four security personnel), arrests of 2,217 individuals (including 165 minors and 46 university students). It confirmed injuries of at least 51 from live ammunition or pellet fire. Additionally, the regime deployed internet blackouts and throttling in regions experiencing active protests; Cloudflare reported a 35 percent decrease in internet traffic in Iran on January 3, with citizens reporting frequent outages and severely degraded connection speeds. These measures served both to limit the coordination of future protests and to prevent the dissemination of images and information about the security forces' violence to international audiences.

An Admission of Weakness: The Iraqi Militia Deployment: Symptom of Regime Weakness — Why the IRGC Needs Foreign Mercenaries

Perhaps the most revealing development in the IRGC's response to the protests was the decision to deploy approximately 800 Iraqi Shia militia fighters to Iran beginning around January 2–3 and continuing through January 6, 2026.

According to Iran International, these militias were recruited from organisations including Kata'ib Hezbollah, Harakat al-Nujaba, Sayyid al-Shuhada, and the Badr Organization—all groups that have received substantial financial, military, and organisational support from the IRGC's Quds Force and are therefore considered extensions of Iranian state power.

The militias were transported across the Iran-Iraq border via the Shalamcheh, Chazabeh, and Khosravi crossing points, officially under the cover of "pilgrimage trips to the holy shrine of Imam Reza in Mashhad." However, witnesses reported that they were assembled at a base linked to Khamenei in Ahvaz before being dispatched to various regions to participate in the suppression of protests.

The decision to import foreign militia forces constitutes a remarkable admission of the IRGC's assessment of its own constraints. As analysts and sources quoted in Iran International noted, the Iranian regime appeared to harbour concerns that its own security forces—the IRGC, the Law Enforcement Command, and the Basij paramilitary volunteers—might either be reluctant to engage in lethal suppression of their own fellow citizens or were numerically insufficient to manage unrest across more than 100 cities simultaneously.

By recruiting Iraqi militias with no cultural or familial connections to the Iranian population, the regime sought to create a force that might be more willing to employ violence without hesitation and whose depredations might be more easily blamed on "foreign interference" or "sectarian militants."

However, the deployment of Iraqi militias also signals a cascade of regime vulnerabilities.

First, it demonstrates that the Islamic Republic, despite commanding the IRGC—one of the world's largest military organisations—perceived itself as unable to suppress domestic unrest with its existing apparatus.

Second, it reveals the regime's awareness that importing foreign forces might delegitimise the crackdown in the eyes of ordinary Iranians and provide additional justification for the protesters' claims that the regime is fundamentally alienated from the Iranian population.

Third, and perhaps most significantly, it indicates that the IRGC's financial resources are sufficiently strained that expanding its own forces may be prohibitively expensive, necessitating reliance on cheaper foreign auxiliaries.

Iraq itself, nominally an independent nation-state, has allowed this deployment despite potential domestic political blowback, suggesting both the depth of Iranian-Iraqi militia connections and the weakness of Iraq's state apparatus in constraining proxy forces.

The Interference Narrative: Allegations of Foreign Involvement: Separating Rhetoric from Evidence — What the US and Israel Actually Did

The Islamic Republic's official narrative regarding the protests has been that they represent a coordinated foreign conspiracy orchestrated primarily by the United States and Israel, with potential support from other adversaries.

Multiple regime figures have articulated this framing: the Judiciary Chief declared that protesters were receiving "aid" from foreign enemies; military leadership warned the US and Israel against "interference"; and the Foreign Ministry issued statements condemning what it characterised as Washington's and Jerusalem's "interventionist and deceptive" remarks.

Examining the evidence reveals a more nuanced reality. The United States and Israel have indeed issued public statements supporting the protesters and warning Iran's government against excessive violence.

President Donald Trump stated on January 4, 2026, that "If they start killing people as they have in the past, I think they are going to get struck by the United States," and subsequently escalated to more explicit language: "The United States of America will come to their rescue. We are locked and loaded and ready to go." Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has publicly praised the protesters' courage and determination.

The US State Department's Persian-language social media accounts have repeatedly voiced support for demonstrators. These statements are unambiguous in their sympathies and constitute political support for the protest movement.

However, there exists no credible evidence—and Iran has presented none—that the United States or Israel has provided material support, financial resources, weapons, or operational coordination to the protest movement.

No intercepted communications, defector accounts, or leaked documents have demonstrated direct foreign involvement in instigating, financing, or directing the protests. The temporal sequence of events contradicts claims of foreign orchestration: the rial's collapse occurred on December 28, and protests erupted organically within hours among merchants whose livelihoods were destroyed; no foreign intelligence service could plausibly have orchestrated such a response with the precision and authenticity visible in early protest videos.

The geographic expansion and ideological evolution of slogans, while potentially influenced by exiled opposition figures like Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, emerged organically from the Iranian population without evidence of external direction.

What the US and Israel have undertaken is what might be characterised as "rhetorical intervention"—the use of public statements to signal support for the protesters, delegitimise the regime's narrative, and increase the perceived international cost of violent suppression.

Whether such rhetorical support constitutes "interference" in Iran's internal affairs depends on one's definition, but it does not constitute the material, financial, or operational involvement that Iran has alleged. The protests are fundamentally rooted in Iran's structural economic crisis and in three decades of accumulated discontent with the Islamic Republic's governance.

Notably, prominent Iranian activists and human rights defenders inside the country have been emphatic in rejecting both foreign military intervention and the regime's characterisation of the protests as externally orchestrated.

They have distinguished between international support—diplomatic pressure, sanctions against regime officials responsible for human rights abuses, public advocacy—and military intervention or regime change operations.

This distinction reflects an understanding that genuine legitimacy for any successor government would require that the transition emerge from within Iran rather than be imposed by external powers. The activists' position also undermines the regime's claims that protesters are puppets of foreign powers; if they were truly foreign-controlled, they would presumably welcome explicit external support and intervention.

The Symbols Speak Louder: Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi: Symbol or Leader? — Monarchy's Return as Protest Metaphor

The role of Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi II, the exiled son of Iran's last shah, merits examination as a potential vector through which foreign influence might be channelled or as a symbol of broader change that transcends any individual's direction.

Beginning in early January 2026, Pahlavi issued video calls to Iranians, urging them to join the protests and to coordinate demonstrations at specific times (particularly 8 PM on January 7 and 8). His appeals invoked nationalist sentiment, calling on military personnel to defect and join the people. They explicitly positioned themselves as an alternative leadership figure capable of serving as an interim ruler during a transitional period.

Pahlavi's intervention has been neither incidental nor insignificant. His calls for coordinated demonstrations, amplified through social media and diaspora networks, coincided with the protests' expansion and intensification. Analysts at the Center for Strategic and International Studies assessed that Pahlavi's January 7 call could represent a "turning point" if it generated sufficient participation to create a narrative of inevitable regime collapse.

Videos circulated showing what appeared to be large crowds responding to Pahlavi's calls, and some observers noted that monarchist slogans increased in frequency following his appeals.

However, the evidence suggests that Pahlavi functions more as a symbol and beneficiary of the protests rather than as their orchestrator. The slogans invoking monarchy emerged organically within days of the protests' beginning, before Pahlavi had issued explicit calls for regime change; his subsequent appeals amplified and channelled sentiment that was already present rather than initiating it.

Critically, Pahlavi has not provided financial support, weapons, or other material resources to the protest movement; his intervention consists purely of rhetoric and symbolic positioning. While his appeals to military personnel to defect may encourage dissidents within the IRGC and law enforcement forces, there is no evidence of large-scale defections or of military units refusing orders to suppress protests—suggesting that Pahlavi's rhetorical appeals, however symbolically potent, have not fundamentally altered the security forces' operational cohesion.

Furthermore, the diversity of the protest movement's ideological expression—encompassing not only monarchist sentiment but also secular republican demands, ethnic minority autonomy aspirations, and leftist economic critiques—indicates that no single leader or external actor is directing the movement.

The slogans range from "Long live the Shah" to "Neither Gaza nor Lebanon, My Life for Iran" to explicitly anti-capitalist critiques of the regime's oligarchic corruption.

This ideological plurality, while potentially complicating any post-regime transition, reflects the authentic heterogeneity of Iranian society rather than coordination by a unifying external authority.

The Question That Haunts: The Question of Duration: Will the Protests Persist or Dissipate? — Historical Lessons and Structural Imperatives

Determining whether the current unrest will persist for weeks, months, or years—or, conversely, whether it will be suppressed within days despite its current scale—requires examining both historical precedent and the structural conditions underpinning the protests.

Historical precedent offers mixed guidance. The November 2019 fuel price protests were suppressed with extraordinary violence within days, despite causing perhaps 304 to 1,500 deaths and resulting in what some observers characterised as a "massacre." The 2022–2023 Woman, Life, Freedom protests, by contrast, persisted in waves over months, with initial intense mobilisation giving way to periodic flare-ups triggered by new grievances (executions, further restrictions on women's rights, etc.).

These protests ultimately diminished in frequency and intensity without achieving explicit regime change, though they fundamentally altered the psychological relationship between the Iranian population and the state, establishing an expectation that public defiance, however costly, was possible and justified.

The current unrest differs from both precedents in crucial respects. Unlike the 2019 fuel protests, which centred on a discrete price increase that the government could theoretically reverse, the current crisis stems from structural economic collapse whose resolution would require either fundamental policy reforms (ending support for regional proxy militias, negotiating sanctions relief, restructuring the fiscal system) or external interventions (sanctions relief, foreign investment) that are not within the regime's immediate control.

Unlike the 2022–2023 Amini protests, which focused on gender-based violence and social restrictions that the regime could theoretically address through cosmetic policy changes, the current demonstrations explicitly demand the regime's overthrow. No policy adjustment short of a fundamental transformation can satisfy demands for Khamenei's removal or the restoration of the monarchy.

Additionally, the economic conditions underpinning the current unrest are, by all available evidence, deteriorating rather than stabilising.

The government's announced subsidy of approximately seven dollars per household per month is acknowledged even by regime sources to be inadequate to address the food inflation crisis. The rial continues to depreciate; having plummeted to 1.5 million to the dollar on January 6, it may decline further absent dramatic external developments (sanctions relief, cessation of military conflicts, or large-scale foreign investment).

Unemployment, particularly among youth and university graduates, remains high and likely to worsen as economic contraction deepens. These conditions suggest that the underlying drivers of protest will persist and likely intensify over the coming weeks and months.

Analysts familiar with Iranian protest dynamics have noted that previous crackdowns, however successful in suppressing immediate demonstrations, never addressed the underlying grievances. Each cycle of protests has been followed, within months to years, by new waves of unrest driven by accumulated grievances and eroded confidence in state institutions.

The current moment differs in the depth and breadth of both the economic crisis and the loss of regime legitimacy; there is less basis for believing that suppression followed by modest concessions will restore stability, as it has in previous cycles.

However, the regime's demonstrated willingness to deploy lethal force against civilians, including children, combined with its importation of foreign militia forces and its control over communications infrastructure, should not be underestimated. History provides examples of regimes that, through extraordinary brutality and control of information, have suppressed protests despite conditions of extraordinary economic hardship.

The Syrian regime under Bashar al-Assad sustained itself through civil war despite economic collapse, mass displacement, and international isolation. North Korea has maintained control despite widespread famine and poverty. The Chinese Communist Party has suppressed dissent despite rapid economic changes, creating displaced workers and ideological confusion.

The most plausible assessment, based on available evidence and comparative analysis, is that the current Iranian protests will persist in some form for months rather than dissipating within weeks. The economic crisis underpinning unrest will not be resolved without fundamental changes that the regime appears unwilling or unable to implement.

The loss of regime legitimacy, visible in demands for Khamenei's overthrow and the invocation of monarchy, represents a psychological threshold that suppression may defer but is unlikely to reverse. However, the regime's security apparatus, supplemented by imported militia forces and operating without effective international intervention, likely has sufficient coercive capacity to prevent the emergence of a nationwide unified uprising capable of directly challenging the IRGC's control over key state institutions.

The outcome, therefore, may be neither regime collapse nor complete suppression, but rather a prolonged conflict combining periodic demonstrations, security force crackdowns, possible localised insurgency in ethnic minority regions, and the slow erosion of the regime's capacity to govern effectively. Such an extended conflict would exact enormous human costs, further devastate the economy, and create space for external actors to increase pressure or intervene if they assess that regime collapse has become feasible.

FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS AND POTENTIAL TRAJECTORIES

Futures Fractured: Three Scenarios for the Coming Crisis

The path forward for Iran's political crisis encompasses several possible scenarios, each with distinct implications for the country's population, regional stability, and international relations.

The first scenario is continued suppression and eventual stabilisation of the regime through overwhelming force, internecine crackdowns targeting suspected sympathisers within state institutions, and modest economic concessions. In this scenario, the IRGC and Basij would intensify lethal force application, potentially resulting in death tolls numbering in the hundreds or thousands.

The regime would likely increase internet blackouts and restrict access to communications platforms. It would expand the deployment of foreign militias or accelerate the recruitment of domestic forces willing to engage in mass violence.

Economic measures would be implemented—perhaps including negotiations with the International Monetary Fund or individual foreign governments for sanctions relief or limited investment—that would provide temporary relief but would not resolve structural fiscal problems. Over time, the psychological shock of failed protests would dampen widespread enthusiasm for sustained mobilisation, and the regime would consolidate control over the security apparatus.

However, this stabilisation would rest on increasingly naked coercion rather than any restoration of legitimacy, creating the conditions for subsequent waves of unrest.

The second scenario involves cascading regime institutions and the emergence of competing power centres unwilling to maintain the current structure. In this scenario, divisions within the IRGC leadership, between the IRGC and the civilian government, or among senior religious authorities would prevent coordination of a unified security response. Significant defections of military or security personnel would occur, providing the protest movement with access to weapons and operational knowledge.

Regional security forces or ethnic minority militias might seize the opportunity to challenge central authority. International actors, assessing that the regime's collapse had become likely, would intensify pressure through military strikes on Iranian nuclear and missile facilities or through explicit support for successor regimes. In this scenario, the outcome could range from the emergence of a military junta to the installation of a transitional government dominated by exile figures like Reza Pahlavi to the fragmentation of Iran into autonomous regions controlled by ethnic and religious communities or warlord factions.

The third scenario, intermediate in likelihood and consequence, involves a prolonged phase of contested state authority combining intermittent protests, security force crackdowns, and localised insurgency, particularly in ethnic minority regions. In this scenario, the regime would maintain formal control over Tehran and major urban centres while losing effective authority in the peripheral areas.

Baloch, Kurdish, Lur, and Arab minorities, encouraged by the visibility of their grievances and emboldened by the central authority's distraction with the main protest movement, would escalate demands for autonomy or independence. Organised nationalist groups would engage in operations against security forces, creating a multi-theatre conflict that would strain the regime's resources and create opportunities for international actors to provide support to anti-regime forces.

Economic conditions would continue to deteriorate without resolution of the underlying fiscal crisis, perpetuating the conditions for mobilisation. In this scenario, Iran would enter a prolonged period of instability lasting years, with enormous humanitarian consequences, regional spillover effects, and the potential for external intervention at multiple stages.

Each scenario carries profound implications for the Iranian population, the region, and the international system. The first scenario preserves formal regime continuity but deepens the authoritarianism and coercive apparatus. The second scenario offers the potential for fundamental change but also risks civil conflict and external intervention, with unpredictable consequences.

The third scenario creates conditions for a humanitarian catastrophe through prolonged conflict while remaining compatible with the regime's nominal survival. Notably, none of these scenarios involves the regime's easy restoration of legitimacy or a return to the status quo ante of December 2025.

CONCLUSION

When History Accelerates: Iran at the Threshold

The Iranian protests that commenced on December 28, 2025, and have persisted through January 8, 2026, represent a watershed moment in the Islamic Republic's trajectory. Unlike previous cycles of unrest driven by discrete grievances susceptible to policy adjustment, the current crisis stems from structural economic collapse and has crystallised into explicit demands for regime change.

The government's response—escalating from relative restraint to lethal force, importing foreign militia forces to supplement the domestic security apparatus, and implementing coordinated campaigns of intimidation and coercion—reveals both the regime's perceived imperative and its underlying weakness.

The allegations of foreign orchestration that the regime has deployed to delegitimise the protests do not withstand scrutiny. While the United States and Israel have issued public statements supporting the demonstrators, there exists no credible evidence of material foreign involvement in instigating, financing, or directing the protests.

The unrest is fundamentally rooted in Iran's structural economic crisis, compounded by decades of accumulated discontent with the Islamic Republic's governance, prioritisation of regional proxy spending over citizen welfare, and systematic corruption. Foreign actors have sought to advance their interests through rhetorical support, but they have not created the conditions for protest.

The question confronting the international community is not whether the current unrest will immediately result in regime collapse, but rather whether the structural conditions underpinning the protests will persist, intensify, or be ameliorated through regime policy changes or external interventions.

The evidence suggests that without a fundamental transformation—cessation of proxy warfare, dramatic restructuring of expenditure priorities, successful sanctions-relief negotiations, or massive foreign investment—the underlying drivers of unrest will persist and likely intensify. The regime's reliance on lethal force and imported militia forces indicates that it possesses adequate coercive capacity to prevent immediate collapse but insufficient legitimacy to restore stable governance.

The duration and intensity of the coming conflict remain uncertain, but the trajectory points toward months or years of contested state authority rather than rapid resolution in either direction.

For the Iranian population, this trajectory promises extraordinary hardship: deepening economic crisis, expanding state violence, and the potential for civil conflict. For regional actors, it creates space for escalation in proxy competition, for opportunities to intervene militarily, and for the redrawing of Middle Eastern power configurations.

In the international system, it represents a test of whether established norms regarding national sovereignty and non-interference will hold when a significant regional power faces potential collapse, or whether Great Power competition will override them. The outcome of Iran's current crisis will reverberate across global politics for decades.