From Kent State to Minneapolis: What Deadly Government Force Teaches the Country

INTRODUCTION

SEEING PEOPLE DIE ON CAMERA

In recent years, many people in the United States have watched phone videos from Minneapolis that show federal immigration officers shooting and killing two different 37-year-old citizens, Renee Good and Alex Pretti. The scenes are hard to forget. In one video, a mother in a car near her home is shot within seconds of officers approaching her. In another, a nurse at a protest ends up on the ground surrounded by agents and is shot after trying to help someone else.

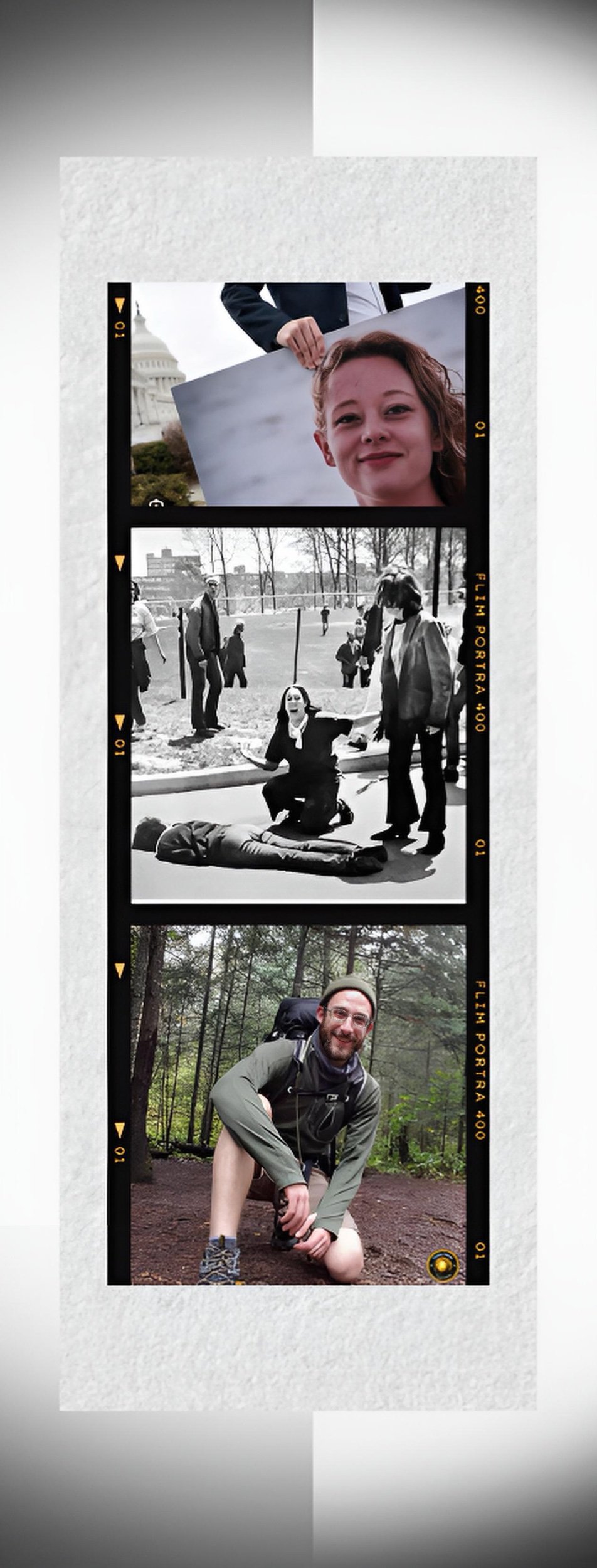

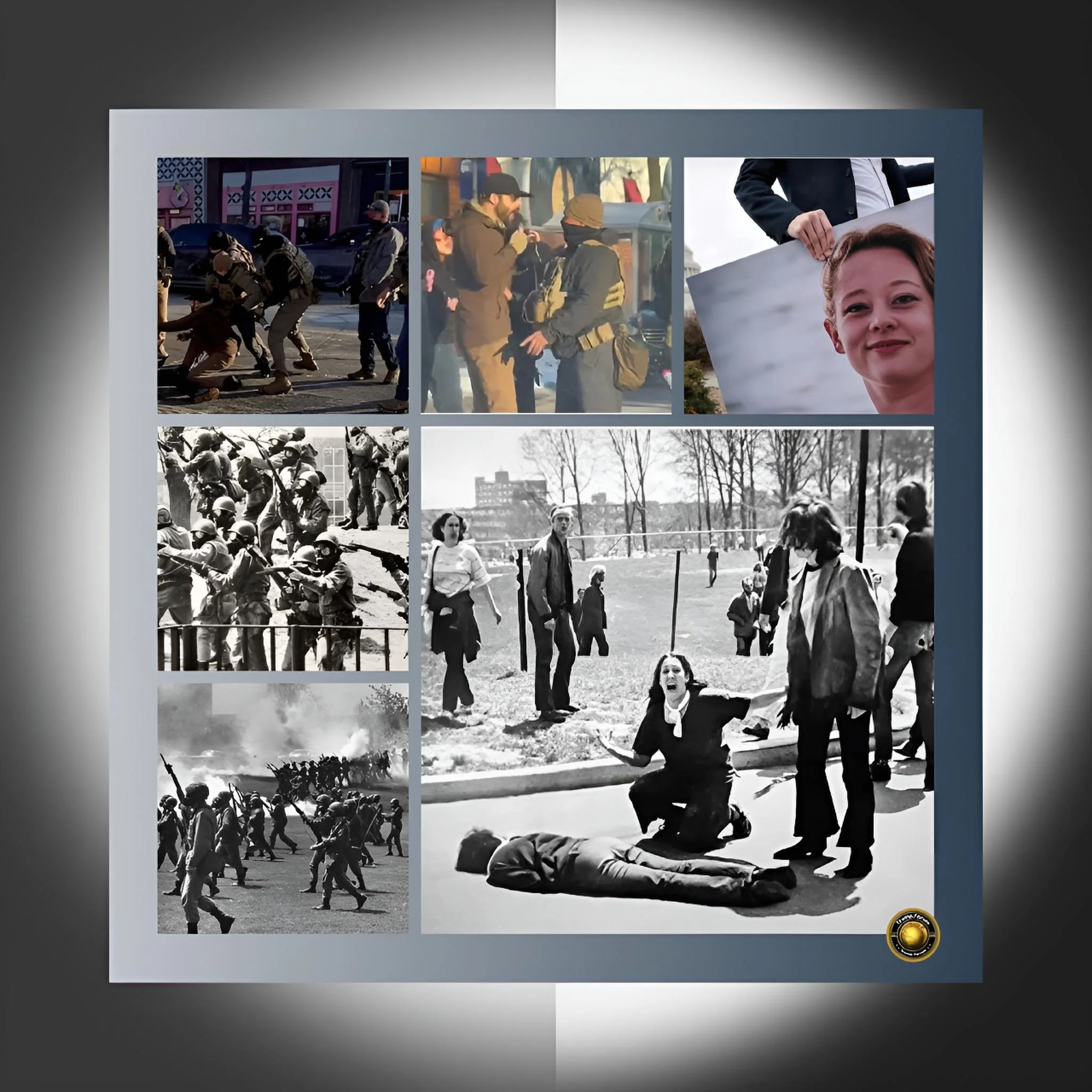

For older generations, these images feel disturbingly similar to the old black-and-white photos from Kent State University in 1970. In those photos, young students lie dead or wounded on a campus hillside after soldiers from the Ohio National Guard fired into a crowd during an anti-war protest.

One of the most famous pictures shows a woman screaming over the body of a student who has just been shot. That photograph, like today's phone videos, traveled far and wide. It made millions of people ask: how can a democratic government turn deadly force on its own people?

FAF article explains in clear language what happened at Kent State, what is known about the Minneapolis shootings, what "state violence" means, and what lessons these events may hold for the future. It uses everyday examples to show how decisions made by officials far from the street can shape life-and-death moments on the ground.

WHAT HAPPENED AT KENT STATE IN 1970

In early May 1970, the United States had been fighting in Vietnam for years. Many young Americans, especially college students, believed the war was wrong and wanted the government to end it. When the president announced that U.S. troops would expand the war into neighboring Cambodia, anger boiled over on campuses across the country, including at Kent State University in Ohio.

At Kent State, students organized rallies and marches. Some protests turned rowdy. In town, people broke store windows; on campus, an ROTC building linked to the military was burned. No one was killed or injured in these earlier events, but they alarmed local leaders. The mayor asked the governor for help. The governor sent in the Ohio National Guard—soldiers carrying rifles and bayonets—to take control of the campus.

Imagine a college campus that suddenly looks like a military zone: troops in helmets, armed vehicles, and students who one day are going to class and the next find themselves facing soldiers. The governor publicly called the protesters terrible names and described them almost like enemies in a war. In that kind of atmosphere, it became easy for some officials and citizens to see the students not as young people with strong opinions, but as dangerous troublemakers who needed to be stopped.

On May 4, a large group of students gathered on the campus commons for a planned protest, even though officials said the rally was banned.

Around noon, National Guard officers tried to break up the crowd. They drove a jeep through the students with a bullhorn, ordering people to leave, but many could not hear well and many simply refused to go. The Guardsmen fired tear gas, but the wind blew much of it away. Some students shouted and threw rocks from a distance. The soldiers moved across a large open field and up and down a hill, pointing their rifles.

Then something devastating happened. As the Guardsmen climbed back up the hill, a group of them turned, aimed, and fired their weapons toward the students and bystanders.

The shooting lasted only about 13 seconds, but in that short time they fired dozens of rounds.

Four students were killed. Two of them had only been walking nearby on their way to class, not even taking part in the protest. Nine others were wounded, one of them permanently paralyzed.

Later, a national commission studied the tragedy and concluded that the soldiers did not face a serious enough threat to justify shooting. The commission said the use of live ammunition against unarmed students was "unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable."

In simple terms, that means there was no good reason to fire. The report also pointed out that bringing heavily armed soldiers with little training in crowd control onto a college campus was itself a dangerous choice. It made a deadly outcome much more likely.

WHAT "STATE VIOLENCE" MEANS IN EVERYDAY TERMS

To see why Kent State and the Minneapolis shootings cause such strong reactions, it helps to understand the idea of "state violence" in plain language.

Every modern country has a government, and that government has special powers that ordinary people do not. Police can stop, search, and arrest people. Soldiers can be sent into dangerous situations with weapons. Immigration officers can detain and deport people. These powers all involve force—sometimes physical pushing and holding, sometimes weapons, and in rare cases, deadly force.

In a democracy, the basic idea is that this special power is given to the state so it can protect everyone. The police are supposed to stop assaults, robberies, or killings; soldiers are supposed to defend the country; immigration officers are supposed to follow agreed-upon rules about who may enter and stay. The state is allowed to use force when needed to enforce laws and protect life, but it is expected to use as little force as possible.

"State violence" is a way of talking about what happens when this power is used in harmful or unfair ways. If officers beat or shoot people who are not a real threat, if they silence peaceful protesters with weapons, or if they treat some groups as less deserving of safety, then the state's violence is no longer just a tool for protecting everyone. It becomes a danger, especially for those seen as outsiders or troublemakers.

A simple example helps. Imagine a neighborhood where young people like to gather in a park to hold signs and chant about an issue they care about. If the city sends community officers who talk to organizers, set clear rules, and only step in when someone is in serious danger, that is the state using its power carefully.

If, instead, the city sends armored vehicles, officers in full combat gear, and starts firing rubber bullets or live rounds when people shout or refuse to move quickly enough, that is state violence in a much darker sense. The tools may be the same—uniforms, weapons, shields—but the purpose and the restraint are very different.

WHAT HAPPENED TO RENEE GOOD AND ALEX PRETTI

The stories of Renee Good and Alex Pretti show how quickly state power can tip from "keeping order" into deadly force, especially when federal agents are dropped into tense city situations.

Renee Good was a 37-year-old mother of three living in Minneapolis. One winter morning, she drove her child to school and was returning through her neighborhood. At the same time, immigration officers were operating nearby. On a narrow, snowy street, Good's vehicle became involved in a sudden encounter with agents whose own car was stuck.

In a matter of seconds, the situation went from shouting to gunfire. Neighbors' videos show officers surrounding her car and shots being fired into her windshield. Good died where she sat.

Think about how ordinary that morning was up until that point. Most parents have had the experience of rushing to get a child to school and then hurrying on to the next task. The distance between that everyday scene and a fatal shooting is measured in a few unwise steps: where officers chose to park, how they chose to approach, whether they stepped in front of the car, and how quickly one of them decided to pull the trigger. Each of those choices was shaped by training, policy, and attitude.

Seventeen days later, another tragedy unfolded. Protests had broken out in Minneapolis over Good's killing and over broader immigration raids.

At one such protest, 37-year-old nurse Alex Pretti was present. He worked in an intensive care unit and, like many health-care workers, had spent years trying to preserve life. On that day, he was helping direct traffic and recording federal agents with his phone as they pushed people back.

When one agent shoved a woman to the ground and used pepper spray, Pretti moved to help her, putting his arms around her to shield or lift her.

Several agents then tackled them both. In the struggle, they discovered a handgun in a holster at his waist. Pretti had a legal permit to carry that weapon, and there is no evidence he had drawn it. Nevertheless, once the gun was noticed, the situation escalated quickly. Within seconds, agents on top of him opened fire, and he died from multiple gunshot wounds.

For many observers, these two stories feel like warnings that ordinary life—driving a child to school, attending a protest, helping someone on the ground—can cross paths with armed state power in ways that ordinary people cannot control. When the state's first answer to confusion or resistance is a gunshot, it becomes very hard to believe that the power to use force is truly reserved for the most extreme situations.

WHY THESE SHOOTINGS MATTER FOR DEMOCRACY

Events like Kent State and the Minneapolis shootings do more than break hearts; they shake people's faith in the basic deal between the government and the public.

In a healthy democracy, citizens accept that the government has special powers partly because they believe those powers will not be used against them without very strong reasons.

You might not like getting a speeding ticket, but you accept that the police have the right to stop you for driving dangerously. You understand that if someone is actively shooting in a crowd, officers may have to shoot that person to protect others. There is a balance: the state gets power; in return, it promises restraint and fairness.

When people see unarmed students lying dead on a campus, or a mother or nurse killed in unclear circumstances, they begin to doubt that balance.

They ask: if this can happen to them, what protects me?

Will officers assume the worst about me because of my race, my immigration status, my political views, or simply because I am in the wrong place at the wrong time?

Will the story the government tells after the fact match what really happened—or will it always lean toward defending its own agents?

These doubts spread. Some people grow afraid and stay away from protests even when they care deeply about the issues. Others become angrier and more willing to confront officers, which can make future clashes more intense.

Trust between communities and government weakens. And because democracy depends on people believing that they can safely speak, assemble, and challenge those in power, that weakening of trust harms more than just the immediate victims—it harms the whole system.

HOW GOVERNMENT CHOICES CAN MAKE THINGS WORSE

It is tempting for officials to think that when protests grow or when enforcement actions become controversial, the answer is to show more force. The history of Kent State, the civil-rights era, and more recent protests suggests that this instinct is often wrong.

At Kent State, bringing in troops with rifles into a campus full of angry and fearful young people did not calm the situation. It raised the stakes and made every small incident—a rock thrown, a shout, a misheard order—potentially explosive.

A similar pattern has appeared when federal agents in heavy gear have been sent into cities to face protesters. Instead of reducing tension, their presence can feel like an occupation, prompting more people to come out and resist.

In Minneapolis, sending heavily armed immigration and border agents into dense neighborhoods and protest sites created a dangerous mix. These agents are trained to chase suspects, make arrests, and think in terms of threats. They are not always trained to view a chaotic protest scene as a place where the main job is to protect the rights and safety of everyone present, including those who are shouting at them.

A simple comparison makes this clear. Imagine two responses to a noisy but mostly peaceful protest. In the first, city leaders send negotiators and community officers who talk with organizers, agree on routes, and step in when tempers flare, but avoid charging into the crowd.

The event may be tense, but it ends with people going home. In the second, leaders send in armored federal agents who push, grab, and fire weapons when people do not move fast enough. That second approach might feel strong in the short term, but it is also far more likely to end with people injured or dead—and with deeper anger afterward.

WHAT COULD HELP PREVENT FUTURE TRAGEDIES

No set of rules can remove all risk. But past experience suggests several changes that could make events like Kent State and the Minneapolis shootings less likely.

First, the bar for using deadly force must be kept very high. Officers and agents should be taught, again and again, that firing a weapon is the last option, not the first instinct when things feel out of control. Training should include realistic practice in staying calm under stress, in backing off when a situation is confused, and in recognizing that a person's mere presence with a legal weapon, or their refusal to move instantly, does not automatically mean they are trying to kill.

Second, the state should be careful about who it sends into protest situations. Local officers who know the area and its people are more likely to understand how protests in that city usually unfold. Federal agents who normally work at borders or in raids may be less prepared for the special challenges of crowded, emotionally charged demonstrations. If they must be present, they should receive special training and be clearly told that protecting constitutional rights is part of their job, not an obstacle to it.

Third, honesty and transparency after incidents matter greatly. When the government's first story about a shooting later turns out to be wrong or incomplete, trust is destroyed. Releasing body-camera and bystander footage as soon as possible, allowing independent investigators to examine the scene, and admitting mistakes when they occur are all basic steps toward rebuilding trust.

Finally, leaders should watch their words. Calling protesters "animals," "thugs," or "terrorists" does not just insult them; it sends a signal to officers that harsh treatment is acceptable and that the normal rules may not apply. When leaders instead affirm that protest is a right, that officers must protect both safety and freedom, and that deadly force is almost never acceptable against demonstrators, they help set a safer tone.

CONCLUSION

LEARNING THE RIGHT LESSONS FROM PAST AND PRESENT

Kent State should have taught the United States that when soldiers with loaded guns face students on a campus, terrible things can happen. The deaths of Renee Good and Alex Pretti show that the lesson has not been fully learned. The details differ, but the core problem is the same: when the state uses its special power to kill too quickly, ordinary people doing ordinary things—walking to class, driving home, filming a protest, helping a stranger—can end up dead.

The question now is whether these events will change anything. They could become just more sad stories that fade over time, or they could push the country to take concrete steps: clearer rules, better training, more transparency, and more respectful language toward those who dissent.

Remembering Kent State and Minneapolis side by side makes one thing clear.

The power of the state to use violence inside its own borders is the most dangerous power it has. If that power is not tightly controlled, no one can feel truly safe—no matter how strong the laws look on paper.