From Kent State to Minneapolis: State Violence, Democratic Legitimacy, and the Repetition of History

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

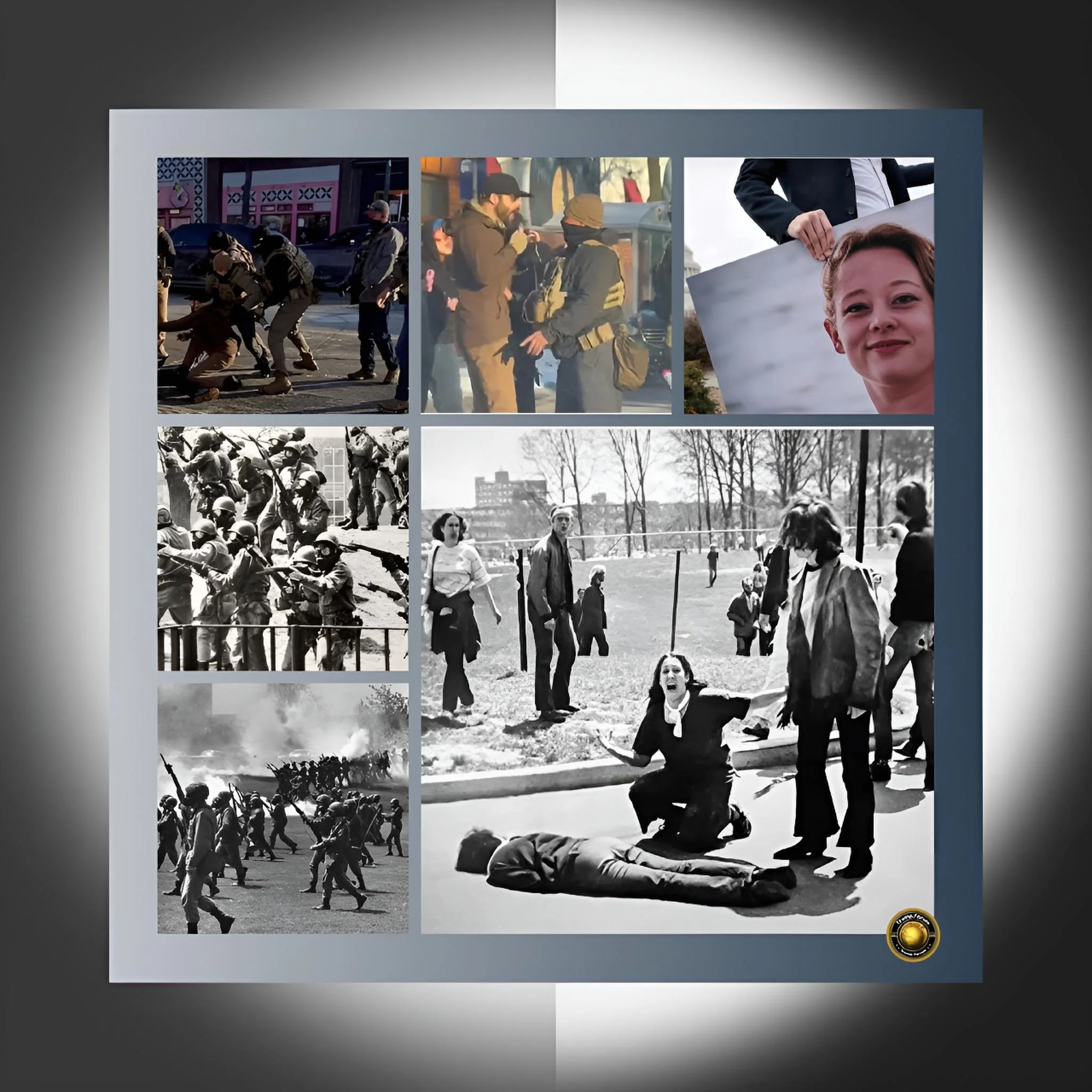

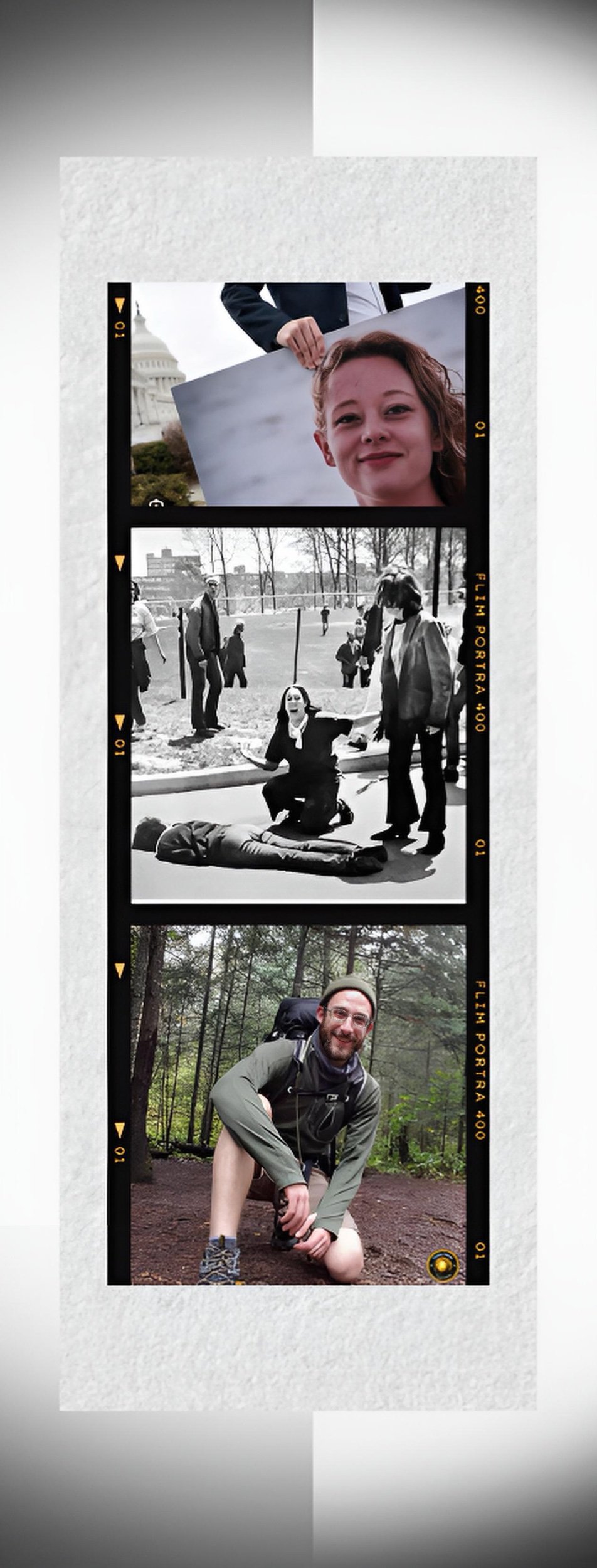

The lethal use of force by state agents against their own citizens has always been a decisive test of American constitutionalism. When Ohio National Guardsmen killed four students and wounded nine at Kent State University in May 1970, the event forced the country to confront the possibility that young people peacefully opposing government policy could be met with military gunfire on their own campus. Kent State became a symbol of state violence turned inward, and of the fragility of rights when "law and order" rhetoric overrides constitutional restraint.

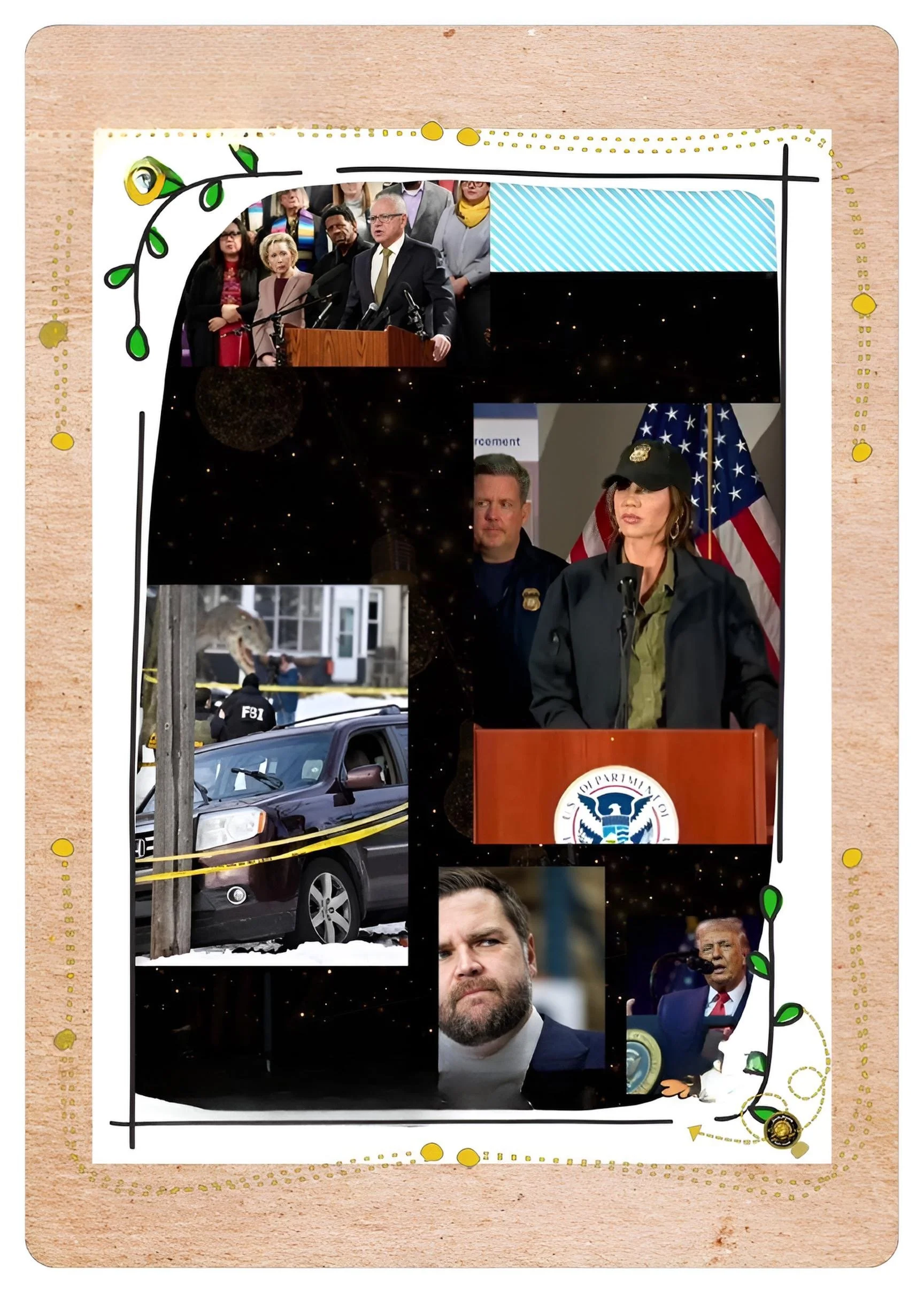

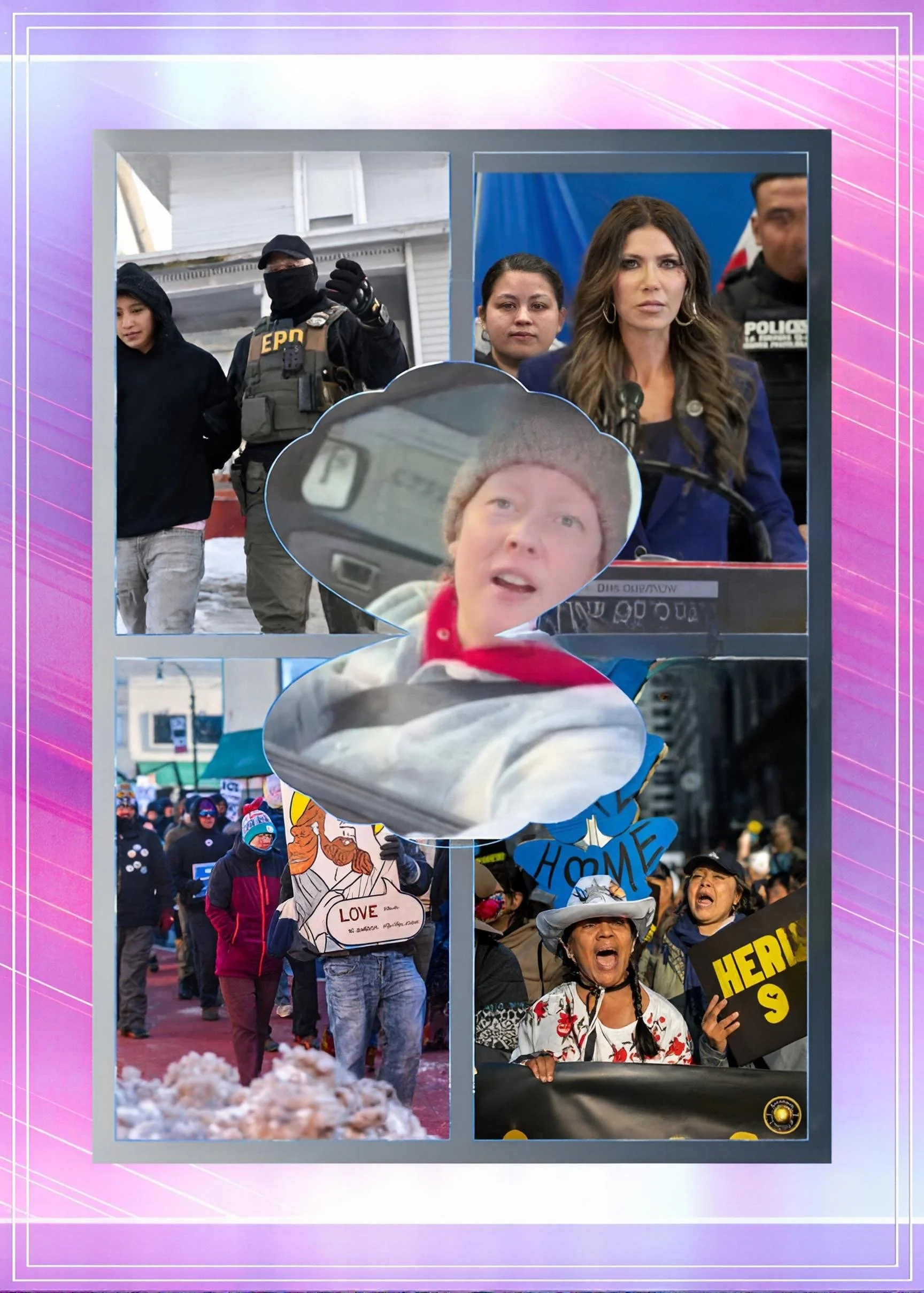

The recent killings of Renee Good and Alex Pretti by federal immigration officers in Minneapolis revive those questions in a new register.

Once again, state representatives armed with the authority to use deadly force have killed citizens in contested circumstances. Once again, widely shared visual evidence has exposed a sharp gap between official narratives that depict the dead as dangerous aggressors and public perceptions that they were, at most, ambiguous threats and at least, vulnerable civilians. And once again, the government's resort to militarized force has escalated, rather than calmed, civic unrest.

The FAF article argues that Kent State is not simply a historical reference point but a continuing diagnosis of how the United States handles dissent. It examines the history and current status of protest policing from 1970 to the present, outlines key legal and institutional developments, analyzes the causal dynamics by which state violence deepens political crisis, and considers what future steps might meaningfully constrain such violence.

The core claim is that unless legal standards, institutional cultures, and public narratives are reshaped to treat protest as a central democratic practice rather than a quasi-insurrection, the United States will remain trapped in a cycle in which state violence repeatedly undermines the state's own legitimacy.

INTRODUCTION

THE RECURRING SHOCK OF LETHAL STATE POWER

The killing of an unarmed or nonthreatening person by government officials produces a kind of shock that outstrips normal partisan conflict. It forces citizens to ask whether the state that claims to protect their rights is, in fact, prepared to extinguish them when they become inconvenient.

The force of that question does not depend on ideological agreement about the victim's politics. It turns on something more elemental: the intuition that the state's unique power to injure and to kill must be subject to strict and visible constraint, or it ceases to be legitimate.

Kent State introduced this problem to a mass television audience. Images of students lying dead or wounded on an American campus, killed not by foreign enemies but by their own government, blurred the line between distant war and domestic peace. Today, smartphone videos of agents shooting citizens in Minneapolis perform a similar function.

They collapse the distance between official press releases and observable reality, inviting millions of viewers to conduct their own, often damning, assessments of what occurred.

The Minneapolis killings are not identical to Kent State. The agencies involved are different, the legal environment has evolved, and the rhetoric of "national security" and "border control" now permeates internal policing.

Yet the underlying structure is strikingly similar: political leaders frame certain groups as threats; heavily armed state agents are deployed into tense civilian environments; and in the resulting confusion and fear, the threshold for lethal violence collapses.

HISTORY AND CURRENT STATUS

FROM KENT STATE TO THE AGE OF MILITARIZED ENFORCEMENT

On 4 May 1970, students at Kent State gathered to protest the widening of the Vietnam War and the presence of military force on their campus. The days preceding the shootings were disorderly but not catastrophic: there had been vandalism, clashes with local police, and the burning of the ROTC building. State officials responded with escalation, summoning the National Guard and endorsing a maximalist "law and order" stance. The governor's public portrayal of student protesters as an internal enemy created a climate in which restraint became politically suspect.

The deployment itself was structurally flawed. Young Guardsmen, minimally trained for riot control, were sent into a dense campus environment with loaded rifles, bayonets, and tear gas.

Communications were poor, the chain of command was confused, and no clear rules of engagement were established. When tear gas failed to disperse the crowd, and some students shouted and threw stones, the situation became a volatile mixture of fear, anger, and lethal weaponry.

The subsequent 13-second volley of rifle fire into a distant crowd was not an unforeseeable accident; it was the predictable outcome of a series of decisions that treated force as the primary instrument of control.

In the years that followed, formal protest management in the United States changed.

Police departments developed specialized crowd-control units and adopted a range of so-called "less-lethal" technologies intended to reduce the use of live ammunition. At the same time, however, policing became increasingly militarized. Federal programs channeled surplus military equipment to local agencies; SWAT teams spread from a few major cities to thousands of jurisdictions; and tactical thinking imported from overseas battlefields found domestic application in drug raids, gang suppression, and, eventually, protest policing.

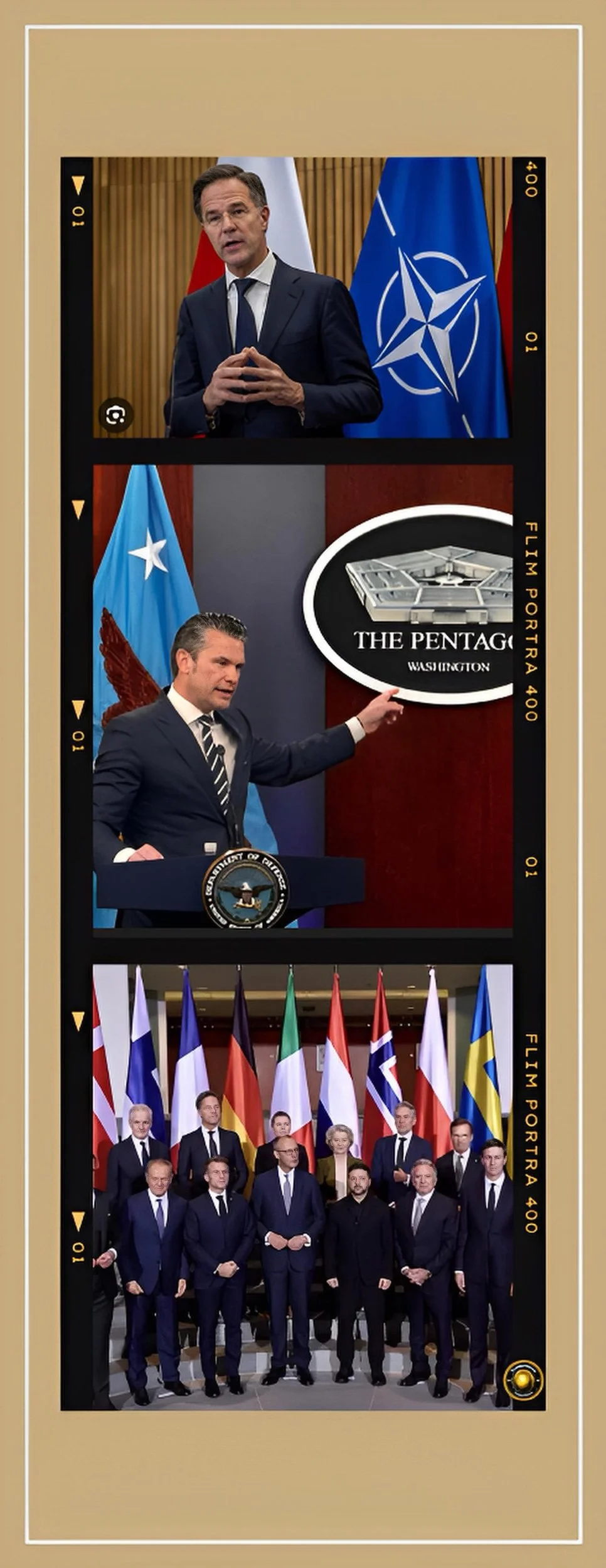

Parallel to this, the federal security apparatus expanded dramatically. Immigration enforcement, in particular, moved from a relatively narrow, border-focused mission to a sprawling interior presence. Immigration officers, border agents, and other federal units began operating more visibly in American cities.

They acquired heavy weaponry, armored vehicles, and broad legal authorities, but often without the local accountability structures that constrain municipal police. The Department of Homeland Security, created after 9/11, consolidated many of these powers and placed them in a counterterrorism frame that blurs the line between foreign adversaries and domestic dissenters.

By the time federal agents in camouflage appeared on the streets of Portland and other cities in 2020 to confront racial justice protesters, a long evolution had already taken place.

The state's capacity to project military-style force into domestic space—once episodic and shocking, as at Kent State—had become normalized.

KEY DEVELOPMENTS

LAW, INSTITUTIONS, AND THE EXPANSION OF STATE VIOLENCE

Kent State exposed the dangers of unregulated force but did not immediately produce comprehensive legal reform. Over the next two decades, however, courts did articulate constitutional limits on police killings.

The Supreme Court's decisions in Tennessee v. Garner and Graham v. Connor established that lethal force is permissible only when a suspect poses a significant threat of serious physical harm and that all force must be "objectively reasonable" in light of the circumstances.

On paper, this jurisprudence was a sharp break from older "fleeing felon" rules that allowed officers to shoot any felony suspect attempting to escape. In practice, the effect was more modest. The doctrine of objective reasonableness has often been applied in a way that heavily defers to officers' real-time perceptions, even when those perceptions later appear mistaken.

As a result, the formal standard that deadly force must be a last resort sits uneasily alongside a pattern of non-prosecution and civil immunity in many contested shootings.

Institutionally, the expansion of federal enforcement agencies has altered the landscape. Immigration and border agencies have acquired overlapping roles in domestic policing, frequently operating with less transparency than local counterparts. Their internal use-of-force policies and training regimes are rarely subject to robust democratic oversight. When such agencies deploy into protest spaces—as in Minneapolis—they carry with them a culture shaped less by the rhythms of ordinary community policing than by the logics of interdiction, pursuit, and threat neutralization.

At the same time, political rhetoric has grown sharper. From the late twentieth century onward, waves of crime panics, drug panics, and national security scares have offered repeated justification for expanding the coercive reach of the state. Protest movements—whether against war, racial injustice, or immigration policy—have often been folded into these narratives, portrayed not merely as dissent but as destabilizing threats that must be controlled. This framing makes it easier, at both the policy and street levels, to see protesters, migrants, and their allies as adversaries rather than as rights-bearing citizens.

LATEST FACTS AND CONCERNS

MINNEAPOLIS AS A CONTEMPORARY FLASHPOINT

Within this historical and institutional context, the Minneapolis killings occupy a particularly charged position. In each case, federal officers were operating in civilian neighborhoods under the banner of immigration enforcement but, in fact, performing a hybrid role: pursuing enforcement objectives, controlling crowds, and projecting federal authority in a politically contested city.

Renee Good was not the target of a long-planned operation; she was a citizen whose everyday life intersected, by bad luck or poor planning, with an armed federal presence on her street. The speed with which the encounter escalated from verbal commands to gunfire highlights the brittleness of a policing strategy that treats quick, aggressive action as a default. It also reveals the danger of introducing heavily armed, externally controlled agents into spaces saturated with the memory of prior police violence.

Alex Pretti's death raises parallel concerns. Here, the context was a protest environment already inflamed by Good's killing and by broader anger at mass raids and detentions. When armed federal agents confront citizens in such settings, their every action is freighted with political meaning. For protesters, they are embodiments of an oppressive policy regime; for the agents themselves, protesters can easily blur into the category of hostile actors. In that atmosphere, the presence of a legally carried firearm, combined with physical struggle and panic, becomes the spark for irreversible tragedy.

A common thread in both cases is the disjunction between official narratives and visual evidence. Statements that present the dead as would-be killers or terrorists sit uneasily beside footage that shows confused, chaotic, but hardly calculated attacks. This gap intensifies public distrust. When the state's story appears to bend reality to exonerate its own agents, citizens reasonably infer that accountability is less a principle than a slogan.

CAUSE-AND-EFFECT ANALYSIS

HOW STATE VIOLENCE DEEPENS CRISIS

State violence does not occur in a vacuum; it is the product of political, institutional, and cultural chains of causation.

Politically, leaders choose whether to describe dissenters as fellow citizens or as internal enemies. At Kent State, talk of "bums" and threats to civilization created a climate in which military confrontation with students was framed as defense of the social order. In contemporary Minneapolis, similar patterns are visible when protesters are branded as "domestic extremists" or immigration raids are sold as battles in a war for national survival. Such language is not mere rhetoric; it shapes how officers interpret ambiguous situations. When someone already coded as a threat makes a sudden move, the mental leap from uncertainty to fatal danger is faster.

Institutionally, the decision to rely on militarized actors in civilian contexts generates foreseeable risks. A Guardsman trained primarily for battlefield conditions, or an immigration agent habituated to aggressive raids, carries a different mindset into a crowd than a community officer with deep local ties. When these agents encounter resistance—even in the form of shouted insults, thrown objects, or efforts to document their behavior on camera—they are more likely to interpret it through a combat lens. The result is a lower threshold for the use of force.

Culturally, each episode of state violence changes expectations. When officers see colleagues escape serious consequences after questionable shootings, they internalize a belief that the institution will protect them. When citizens repeatedly watch the state close ranks around those who kill in its name, they internalize the countervailing belief that appeals to law will be futile. These expectations interact. Officers, feeling shielded, may act more aggressively; citizens, feeling unprotected, may respond with more anger and defiance. The stage is set for confrontation.

The Minneapolis killings illustrate this feedback loop. Good's death, and the perceived impunity surrounding it, drew more people into the streets. The presence of larger crowds and heightened emotions then increased the sense of danger among federal agents, which in turn made the escalation that ended in Pretti's death more probable. State violence thus functions not merely as an endpoint but as a generator of further instability.

FUTURE STEPS

REASSERTING LIMITS ON THE STATE'S DEADLIEST POWER

Breaking this cycle requires more than disciplinary action in particular cases. It demands a re-articulation, in law and in practice, of what the state may and may not do to its citizens.

At the legal level, federal standards governing the use of force by all agencies should be clarified and unified. The core principles are conceptually simple: deadly force must be a last resort; it must be tied to an immediate and specific threat to life; and it must be subject to independent review whenever it is used. Embedding these principles in statute rather than relying solely on judge-made doctrine would strengthen their democratic legitimacy and make them more resistant to erosion.

Institutionally, federal agencies that frequently operate in domestic space should be required to adopt transparent, publicly accessible use-of-force policies and to submit to external oversight. Immigration enforcement should be disentangled, as far as possible, from protest policing; where protest and immigration operations intersect, local authorities with experience in crowd management should take the lead. Training should emphasize de-escalation and the protection of First Amendment rights as core mission elements, not as secondary constraints.

Culturally, political leaders and senior officials must abandon the temptation to demonize protesters. It is possible to condemn property destruction or individual acts of violence without painting entire movements as existential threats. A sober, rights-affirming rhetoric is not mere decoration; it is a signal to both officers and citizens that the state's default posture toward dissent is protection, not suppression.

There is also a need for public remembrance and civic education. Kent State should not be treated as an isolated tragedy but as a case study that informs training, policy, and public debate. The names of more recent victims of state violence, including those killed in Minneapolis, should be woven into this narrative so that the country understands them as part of a continuum rather than as detached incidents.

CONCLUSION

REFUSING REPETITION AS DESTINY

Kent State was once described as a moment when the war came home. The recent killings in Minneapolis suggest that the conditions that made that moment possible—fear of dissent, militarized responses to domestic problems, and a culture of impunity—have not been fully resolved. The state retains, and must maintain, the capacity to use force. But when that capacity is exercised against citizens engaged in or adjacent to political activity, it demands the most exacting scrutiny.

The distance between an armed agent and an unarmed citizen should be measured not only in meters but in norms. It is the work of law, institution-building, and culture to ensure that the space between them is filled with procedures, restraints, and habits of mind that make the pulling of a trigger extraordinarily rare. Kent State revealed how easily that space can collapse.

Minneapolis demonstrates that it can happen again in a different guise. The task for a democratic society is to ensure that these events remain warnings rather than precedents—and that the state's deadliest power is never allowed to harden into a routine tool of domestic governance.