Prague Spring 1968 and the Architecture of Spheres of Influence: How Soviet Lessons Still Shape Great Power Behavior in 2026

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Whole World Was Watching, But Watching Alone Could Not Stop the Tanks

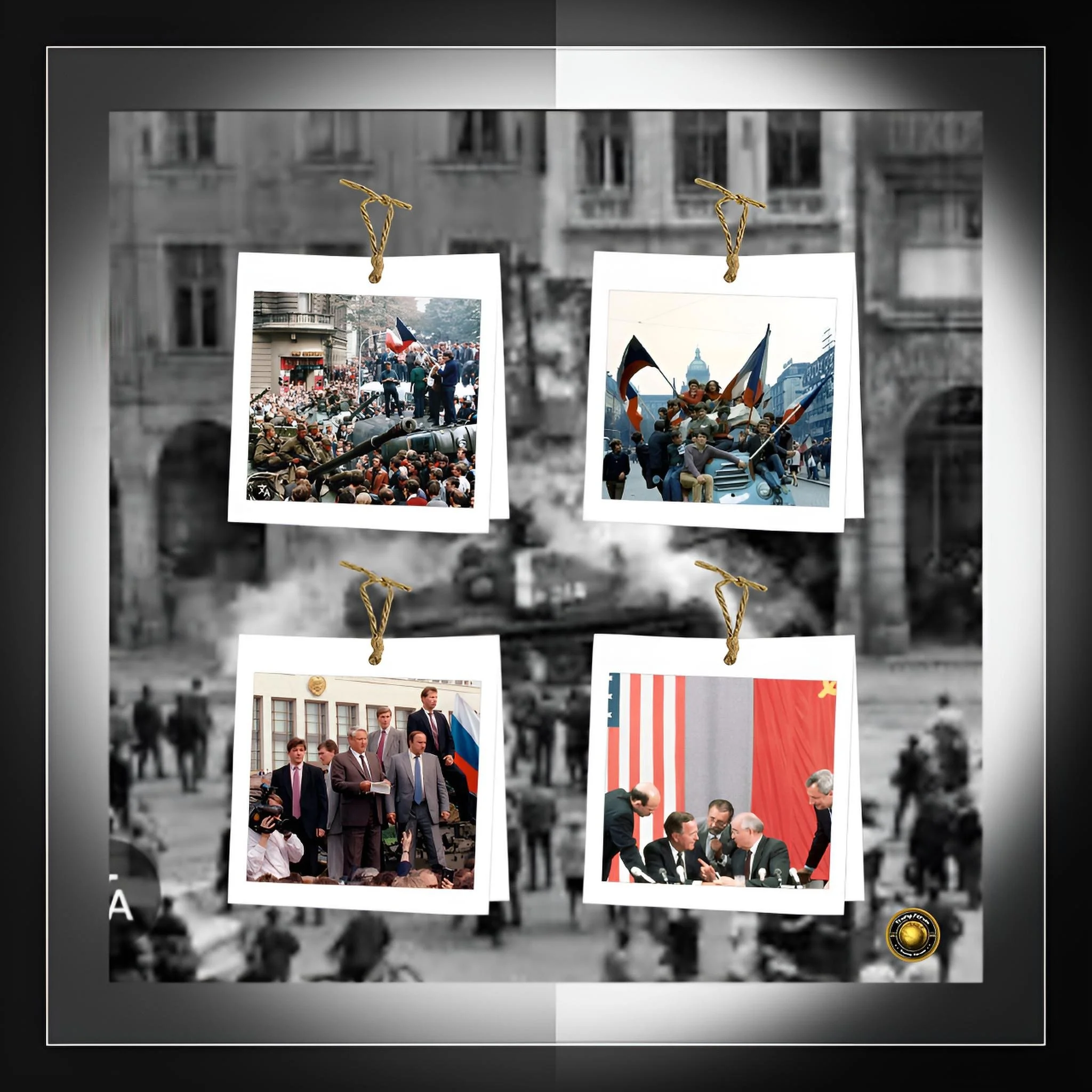

The Prague Spring of 1968 began as an attempt by Czechoslovak communist reformers under Alexander Dubček to create a more humane version of socialism, featuring limited media liberalization, economic decentralization, and civic engagement.

The movement represented a genuine effort to modernize the socialist system while maintaining loyalty to the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet bloc. Between January and August 1968, Czechoslovak society experienced a remarkable flowering of public discourse, as censorship eased, newspapers became lively forums for genuine debate, and ordinary citizens engaged in mass political deliberation.

Yet in August, the Soviet Union and its allies dispatched approximately half a million troops to crush the reform movement and restore hardline control.

The invasion produced the Brezhnev Doctrine, which declared that socialist countries' sovereignty was conditional on their alignment with Soviet-defined "correct" orientation.

Soviet leaders drew three enduring lessons from this episode: that ideological and political deviation on the periphery must be prevented through force if necessary, that Western rhetorical condemnation poses no serious constraint to such interventions, and that control of information environments is essential to preventing further reform contagion.

These lessons remain foundational to Russian strategic culture and explain significant aspects of Russian behavior toward Ukraine, Georgia, and other neighbors in the contemporary period.

Understanding Prague's aftermath provides crucial insight into how great powers manage their perceived spheres of influence, how they rationalize coercive interventions, and why structural reforms to the international system remain so difficult to achieve.

INTRODUCTION: PRAGUE AS A THRESHOLD MOMENT IN COLD WAR HISTORY

The Prague Spring of 1968 occupies a paradoxical place in Cold War historical consciousness. For Western observers, it exemplifies the tragic contradiction of Soviet imperialism: a people reaching toward freedom only to have tanks crush their aspirations. For Eastern European dissidents and later reformers, it serves as both inspiration—proof that alternative visions were possible—and cautionary tale—evidence that partial liberalization without security guarantees proves perilous. For the Soviet leadership and subsequently for Russian strategists, it was a successful management of a critical threat to bloc cohesion, though one that required the articulation of new doctrine to justify the intervention.

The Prague Spring's significance extends beyond its immediate outcomes. It was, simultaneously, a genuine mass political movement; an experiment in reform communism; a media event that revealed the power of information when it escapes state control; a watershed moment in which the limits of Western commitment to peripheral allies became unmistakable; and an episode that established precedents in how great powers police their spheres of influence.

For contemporary observers seeking to understand Russian behavior toward Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and Moldova, the Prague Spring provides an essential historical template: it shows how a threatened great power calculates the costs and benefits of military intervention, how it rationalizes such interventions ideologically, and how it hardens doctrines of regional hegemony in response to perceived contagion risks.

HISTORY: THE PRAGUE SPRING AND ITS ABRUPT CONCLUSION

In January 1968, Alexander Dubček became First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and initiated a program explicitly framed as "socialism with a human face." This was not a call for capitalism, NATO membership, or the dissolution of communist party authority.

Rather, it was an attempt to humanize socialism, to allow a degree of public debate about past injustices, to introduce limited economic decentralization, and to restore legitimacy to communist rule by making it more responsive to public concerns. It was, in the language of the time, a reform-communist project: an effort to preserve socialism while updating its mechanisms and ideology.

The immediate effects on Czech and Slovak society were transformative. Censorship, which had been absolute and comprehensive, was dramatically eased. The press began publishing articles that would have been unthinkable months earlier: investigations into the Stalinist show trials of the 1950s, discussions of economic reform, debates about the role of the communist party, and critiques of hardline orthodoxy. Radio and television programming became livelier and more varied.

Universities became sites of genuine intellectual discussion. Cafes and streets filled with political conversations. Intellectuals, workers, farmers, and ordinary citizens participated in an extraordinary explosion of public discourse. Contemporary observers described it as a "media orgy"—a society intoxicated by the sudden permission to speak what had long been silenced.

For ordinary Czechoslovak citizens, the Prague Spring represented a redemptive moment. It was not a revolution against socialism but an effort to reclaim socialism from bureaucratic rigidity and to make it meaningful.

Dubček himself became an embodiment of reform communism: a figure who seemed capable of modernizing the system without abandoning its fundamental principles. Older members of the population felt that their suffering under Stalinism might finally be publicly acknowledged. Younger people saw possibilities for a different future. The society seemed unified in optimism that change was possible and that it would be orderly, managed from within the party, and ultimately acceptable to Moscow.

The Soviet leadership, however, interpreted these developments with alarm. The Kremlin's concerns were multifaceted.

First, historically, the Soviet Union had learned from the Hungarian uprising of 1956 that allowing one satellite state to move toward liberalization could trigger chain reactions: if Czechoslovakia reformed, why not Poland? Why not East Germany? The specter of contagion haunted Moscow's calculations.

Second, Soviet leaders saw the liberalization of Czech and Slovak media as dangerous in itself. The explosion of public discourse, the questioning of past policies, the discussion of alternatives—these were precisely the dynamics that threatened the legitimacy of hardline communist regimes everywhere. If such openness was permitted in one Warsaw Pact state, it might become difficult to justify its absence elsewhere.

Third, the Soviet leadership worried about geopolitical slippage. Czechoslovakia, under hardline communist control, was a reliable Warsaw Pact member. But if it moved toward the model of Yugoslavia or Romania—states that maintained socialism but exercised greater independence—it might begin to tilt westward. The geographic location of Czechoslovakia, in the heart of Eastern Europe, made such a development particularly threatening.

A Czechoslovakia moving away from strict Soviet orthodoxy could eventually become a bridge between Eastern and Western Europe, undermining the Warsaw Pact's cohesion.

By late spring and summer of 1968, Soviet communications to Dubček became increasingly threatening.

The Kremlin demanded that Czechoslovakia tighten censorship, purge reformers from the party apparatus, and reaffirm Soviet bloc orthodoxy.

Dubček initially resisted, believing he could convince Moscow of his reformism and loyalty. But it became clear that the Kremlin was not interested in reassurance.

From the Soviet perspective, the Prague Spring had already gone too far; the only solution was military intervention.

On the night of August 20–21, 1968, approximately half a million troops from the Soviet Union, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, and Bulgaria crossed into Czechoslovakia. The operation was conducted with overwhelming force: tanks rolled into Prague, other major cities were occupied, and key government buildings were seized. Dubček and other reform leaders were arrested. The Czechoslovak military, under orders not to resist, stood aside. There was no conventional military conflict because conventional military conflict was unnecessary.

What followed was not, however, a silent occupation. The population engaged in mass nonviolent resistance. Workers and students blocked roads with barricades. Citizens painted over street signs and removed them to confuse the invaders. They engaged Soviet and allied soldiers in intense conversations, trying to explain that no "counter-revolution" was underway, that they remained good communists, that they were not enemies of socialism.

Czechoslovak radio and television broadcasts, conducted from improvised studios and transmitters, continued to inform the population about developments and to appeal to international solidarity. The resistance was courageous, dignified, and ultimately futile.

Within days, the overwhelming force of the invasion had achieved its immediate objective. The reform leadership was removed from power. Military control was established. The occupation would last for the next twenty years.

What followed was a period called "normalization"—a carefully orchestrated restoration of hardline communist rule, the repression of remaining reformers, the reinstitution of censorship, and the reassertion of Soviet dominance. The lesson was brutally simple: attempt to reform the system, and you will be crushed.

CURRENT STATUS AND LONG-TERM AFTERMATH: THE BREZHNEV DOCTRINE AND ITS LEGACIES

In November 1968, three months after the invasion, Leonid Brezhnev articulated what became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine. In a speech to the Polish Communist Party, Brezhnev declared that while individual socialist countries possessed sovereignty, this sovereignty was necessarily limited by the interests of the socialist commonwealth as a whole. When forces hostile to socialism attempted to turn a socialist country in a capitalist direction, this was not merely a domestic matter but a concern for all socialist countries. "The sovereignty of each socialist country cannot be opposed to the interests of the world of socialism," Brezhnev declared. In practical terms, this meant that any movement toward political pluralism, media freedom, economic decentralization, or geopolitical realignment could be treated as grounds for military intervention.

The Brezhnev Doctrine represented a significant evolution in Soviet ideology. Where earlier rhetoric had acknowledged the diversity of paths to socialism, the Doctrine asserted a rigid orthodoxy: there was one correct model, and deviations from it threatened the whole bloc. Any Eastern European government that moved away from this model could expect Soviet military force. The doctrine retroactively justified Prague but also established precedent for future interventions.

Inside Czechoslovakia, the aftermath of the invasion was one of profound demoralization and systematic repression. Reformers were removed from positions of authority. Censorship returned with a vengeance. The secret police reasserted control. A generation of intellectuals, writers, and reformers left the country or withdrew into internal emigration. Yet the memory of the Prague Spring endured as a "lost alternative"—proof that a different socialism had once seemed possible and that people had yearned for it.

For later generations of dissidents, Prague became a foundational reference point: evidence that the communist system was not immutable, that change was possible, and that ordinary people could act with courage and dignity in the face of overwhelming force.

Across Eastern Europe, the impact was chilling. Warsaw Pact governments understood that the Brezhnev Doctrine meant the end of any ambitions for domestic reform without prior permission from Moscow.

The doctrine was partially internalized as a rule of the game: Eastern European leaders could manage their internal affairs within parameters defined by Moscow, but any serious attempt at fundamental change would trigger intervention. This constraint shaped Cold War politics for the next twenty years, until the emergence of Gorbachev and ultimately the Soviet Union's collapse.

Interestingly, the Brezhnev Doctrine also had contradictory effects on bloc cohesion. While designed to cement Soviet dominance, it also exposed and deepened fractures. Romania, under Nicolae Ceaușescu, had refused to participate in the invasion and used that refusal as a foundation for a more independent foreign policy. Yugoslavia, outside the Pact, used Prague as further justification for its non-aligned posture.

Albania, which had been moving away from Moscow since the 1960s, saw Prague as confirmation that Soviet communism was an imperialism. Thus, while the Doctrine was meant to strengthen the bloc, it also revealed the limits of Soviet authority over even formally obedient allies.

KEY DEVELOPMENTS: THE INVASION'S GLOBAL IMPACT

The international response to the Prague invasion was sharp but limited. The United Nations Security Council convened to discuss the invasion; the Soviet Union vetoed any resolution critical of its actions. Western governments issued strong condemnations. The invasion appeared in newspaper headlines and television broadcasts worldwide.

The image of Soviet tanks confronting unarmed Czechoslovak civilians became iconic. Yet this global attention did not translate into material intervention.

For NATO countries, the key calculation was straightforward: Czechoslovakia was understood to be within the Soviet sphere of influence, and the risk of direct military confrontation with the Soviet Union was deemed unacceptable.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 had demonstrated how close the world could come to nuclear war; intervening militarily in Eastern Europe seemed likely to escalate into exactly such a scenario. Western leaders, whatever their sympathy for the Czechoslovak people, were not willing to risk nuclear war over a country they had no treaty obligation to defend.

This calculation had profound implications. It meant that people living in Eastern Europe could look to the West and see that rhetorical support, however strong, did not ensure protection. It meant that great powers understood and accepted spheres of influence: the Soviet Union had its zone within which it could act without automatic NATO response, and this zone included Czechoslovakia. It meant that for populations under Soviet control, liberation by external military force was extremely unlikely.

The phrase "the whole world is watching," though most famously associated with anti-Vietnam War protesters at the Democratic Convention in Chicago just weeks after the Prague invasion, captured a broader 1968 sensibility. Movements from Prague to Paris to Mexico City believed that visibility, media coverage, and global public opinion could constrain state violence.

The premise was that if the world was watching, if atrocities were documented and broadcast, the perpetrators would face reputational consequences and possibly external pressure.

The Prague Spring seemed to confirm this belief: the invasion was covered in detail, the resistance was documented, international solidarity movements emerged.

Yet the outcome revealed the limits of this logic. The Soviet Union, having calculated that the benefits of maintaining control over Czechoslovakia outweighed the costs of international condemnation, proceeded with the invasion and sustained its occupation.

International attention produced reputational damage but did not prevent military action or change outcomes.

For Soviet strategists, this was an important learning: global outrage, while undesirable, was manageable and did not necessarily alter the calculation of national interest.

SOVIET LESSONS AND STRATEGIC CULTURE

The Soviet leadership extracted several deep and durable lessons from the Prague Spring. Understanding these lessons is essential for comprehending Russian behavior in the contemporary period.

First, the Kremlin learned that ideological and political deviation on the periphery could not be tolerated and must be prevented through force if necessary. Dubček had not renounced socialism or sought NATO membership, yet his experiment was crushed. This established a principle: within the Soviet sphere, even ideological experiments that remained nominally socialist would be suppressed if they threatened bloc orthodoxy.

The takeaway was not merely that revolution must be prevented but that any significant deviation from Soviet-defined correct orientation must be stopped early, before it could spread. This logic would later justify Soviet intervention in Afghanistan (1979), where a communist regime's moves were deemed insufficiently aligned with Soviet interests.

Second, Soviet leaders concluded that military force remained a legitimate and effective instrument of internal empire management. The invasion succeeded in its immediate objectives: the reform movement was crushed, the country was brought back under control, and the Warsaw Pact remained intact.

There was no direct war with NATO, no nuclear confrontation, no long-term economic disaster for the Soviet Union. From this perspective, the intervention was successful. The cost-benefit analysis suggested that using conventional military force to police one's sphere of influence was rational policy.

Third, the Soviet leadership internalized a certain cynicism about international norms and legal constraints. The invasion of a country and overthrow of its government would normally be considered a violation of international law. The United Nations condemned it.

Formally, it represented an egregious breach of state sovereignty. Yet the Soviet Union faced no serious consequences for this breach. The UN veto protected it from formal censure. No military response was forthcoming. NATO did not mobilize. Western trade continued.

This taught the lesson that international law and norms were only as binding as the willingness of major powers to enforce them, and that in one's own sphere of influence, enforcement was unlikely.

Fourth, Moscow learned that control over information environments was essential to preventing and managing reform contagion. The Prague Spring had been facilitated by the explosion of Czech and Slovak media: if censorship had remained absolute, the reform movement would not have been able to communicate and mobilize.

The invasion itself had been met with continued Czechoslovak broadcasting, which sustained resistance and communicated defiance to the broader population. Soviet leaders concluded that maintaining tight control over media in their own country and in allied states was essential.

This reinforced the Soviet regime's paranoia about information and its investment in censorship, propaganda, and the suppression of foreign broadcasts.

Fifth, the episode confirmed the importance of maintaining bloc discipline through explicit doctrine. The Brezhnev Doctrine was not inevitable; it was a choice to make explicit and unambiguous the limits of satellite sovereignty. By articulating this doctrine, Moscow signaled to other Eastern European leaders and to its own public that military intervention to maintain bloc orthodoxy was not aberration but policy.

This had a chilling effect: it discouraged future reform attempts and made clear that any such attempt would face overwhelming force.

CAUSE-AND-EFFECT: FROM PRAGUE TO CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAN BEHAVIOR

The line from Prague 1968 to Russian behavior toward Ukraine, Georgia, Belarus, and other post-Soviet states is neither direct nor simple, but it is unmistakable. Russia today is not the Soviet Union, but much of the Russian strategic culture that emerged from the Prague Spring remains influential.

Like the Soviet leadership in 1968, contemporary Russian leadership views neighboring states less as fully sovereign entities with legitimate autonomy and more as parts of a "near abroad" where Russia believes it has special rights, interests, and even obligations. When Ukraine moved toward pro-democracy revolutions (the Orange Revolution in 2004, the Euromaidan in 2013–2014) and signaled interest in NATO and EU membership, Russian leaders interpreted this not as benign democratic choice but as hostile encroachment.

Like Soviet leaders observing the Prague Spring, contemporary Russian leaders feared that a successful, Western-aligned democracy on their border would undermine the narrative that Russia's own autocratic path was inevitable and necessary.

The Russian invasion of Crimea and fomentation of conflict in eastern Ukraine in 2014, followed by the full-scale invasion launched in February 2022, reflect the same logic that justified the Prague invasion. From the Russian perspective, Ukraine was attempting to move in a direction incompatible with Russian security interests; therefore, military force was justified.

The rhetoric differs—Putin speaks of protecting Russian-speakers and preventing NATO encroachment rather than maintaining "socialism"—but the underlying structure of thinking is similar.

The doctrine Russia has articulated regarding Ukraine also echoes the Brezhnev Doctrine. Russian officials have repeatedly asserted that Ukraine does not enjoy full sovereign latitude regarding its security alignments, that NATO membership would be unacceptable, and that Russia has a special responsibility for Ukraine's fate.

The language of limited sovereignty for neighbors in Russia's sphere, which Moscow has made explicit, reflects the same logic that Brezhnev articulated in 1968.

Moreover, like the Soviet Union after Prague, Russia has demonstrated its willingness to use military force to enforce what it sees as legitimate interests in its sphere. The invasion of Georgia in 2008, the intervention in Ukraine, and the pressuring of Belarus and Moldova all show a Russia willing to use coercive instruments to prevent neighbors from fully aligning with the West.

And like the Soviet Union, Russia has calculated that the Western response—sanctions, arms deliveries, diplomatic isolation—is manageable compared to the perceived catastrophic risk of losing control of the near abroad.

There is also a lesson about information control. Like the Soviet Union after Prague, Russia has invested heavily in controlling domestic media, suppressing foreign broadcasters, and managing international narratives about its military interventions.

The proliferation of Russian state media agencies, the emphasis on information warfare, and the deployment of disinformation campaigns all reflect, in part, the lesson that information environments cannot be allowed to escape state control if regime narratives are to be maintained.

IMPLICATIONS FOR CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN RESPONSE

For Central and Eastern European states that lived through the Prague Spring or its aftermath, 1968 is not merely historical but deeply personal. The Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and the Baltic countries all remember what it meant to live under Soviet dominance and to have their fates decided in Moscow. The Prague Spring became a symbol of roads not taken, possibilities foreclosed by force.

This historical memory profoundly shapes how these countries have responded to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. They have been among the strongest supporters of Ukrainian resistance and the most hawkish advocates for Western sanctions and military aid. When Czech, Polish, or Baltic leaders speak about Ukraine, they invoke the ghost of 1968: they do not want to see another Prague, another case in which a neighboring state's attempt to choose its own path is crushed without external assistance.

This explains why Poland and the Baltics have been willing to host large numbers of Ukrainian refugees, why they have pushed for stronger military support to Ukraine, and why they have been skeptical of diplomatic solutions that might leave Russia in a dominant position. From their perspective, having once been on the receiving end of Soviet military intervention and Western inaction, they are determined that Ukraine should not face the same fate. They understand viscerally what it means when the West's response to invasion is rhetorical support without material backing.

FUTURE IMPLICATIONS AND LESSONS FOR 2026

As of 2026, the Prague Spring's legacy remains deeply relevant to geopolitics in several ways. First, it serves as a warning for would-be reformers in authoritarian systems.

The lesson many states near great powers draw from Prague is that partial liberalization without security guarantees is perilous. A state cannot simultaneously reform internally and move geopolitically without risking military intervention by a threatened neighbor.

This constraint shapes behavior in countries along Russia's borders, where leaders must decide whether to move decisively toward the EU and NATO (accepting the risk of escalation), remain in Russia's orbit (accepting the constraints on their sovereignty), or attempt to hedge.

Second, the Prague Spring highlights the structural tension between managing escalation and preventing the normalization of aggression. Western policymakers face a dilemma: if they respond too aggressively to Russian intervention, they risk nuclear escalation; if they respond too passively, they risk establishing a precedent that great powers may redraw borders and suppress smaller nations with relative impunity. This is, in many ways, the same dilemma that haunted 1968, and it remains unsolved.

Third, Prague illustrates how lessons are learned and propagated within strategic cultures. Russian strategists can read the Prague invasion as a successful management of a regional challenge.

Western strategists can read it as a cautionary tale about the limits of rhetorical commitment. These competing lessons shape how each side calculates risks and benefits in current confrontations.

CONCLUSION: THE PRAGUE SPRING AS AN ENDURING MIRROR

The Prague Spring of 1968 was a brief moment in which Czechoslovak society reached toward a different future, only to have that possibility crushed by overwhelming force. For the people involved, it was a tragedy: hopes were raised and then destroyed, reformers were imprisoned or exiled, and the society settled into decades of demoralization.

For the Soviet Union, it was a successful assertion of control that required the articulation of new doctrine to justify future similar actions.

Nearly six decades later, the Prague Spring remains a crucial historical reference point for understanding how great powers manage their peripheries, how they rationalize coercive interventions, and how the international community struggles to balance the desire to support smaller states with the fear of escalation into great-power conflict.

The lessons the Soviet Union learned in 1968—that force works, that Western outrage has limits, that information control is essential—remain embedded in Russian strategic thinking.

The countervailing lesson that Central and Eastern European states learned—that external support matters, that military force can be effectively resisted with sufficient backing, that the world does not forget—shapes their responses to contemporary threats.

As of 2026, with Russia's war in Ukraine ongoing and questions about the future stability of the post-Cold War order unresolved, the Prague Spring remains a haunting reference. It shows what happens when a neighboring great power believes it has the right to decide the political fate of smaller states.

It demonstrates the limits of international law and global public opinion when interests collide. And it poses a question that remains unanswered: whether the world can establish a system in which smaller states enjoy genuine sovereignty, or whether great powers will continue to police their spheres of influence through means that ultimately corrode legitimacy and stability.

The tanks that rolled into Prague in 1968 have long since been removed, and the Prague Spring has entered history. But the logic that those tanks embodied—that control of one's sphere of influence is a paramount interest, that force is a legitimate instrument of that control, and that international opposition can be weathered—remains operative in the calculations of great powers.

Understanding Prague is thus understanding not history alone, but the present moment and the stakes it carries.