A Brief Hope, A Brutal Ending, and Lessons That Still Shape the World Today

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Prague Spring 1968: What Happened and Why It Still Matters in 2026

In 1968, Czechoslovakia tried to make its communist system kinder and more open. For a few months, called the Prague Spring, people had more freedom to speak and write. But in August, tanks from the Soviet Union rolled in and crushed this hope. The Soviet leaders learned something important from this: they could use force to stop countries from changing their political systems, and the West would protest but not fight back. Today,

In 2026, Russia still thinks the same way about countries on its borders. Understanding what happened in Prague and what the Soviet Union learned helps us understand why Russia invades Ukraine, why it threatens neighboring countries, and why the world still struggles to protect smaller nations from bigger powers. This article tells the story in clear, simple language and explains why it matters now.

INTRODUCTION: A SPRING OF HOPE IN A COMMUNIST WINTER

Czechoslovakia in the 1960s was a communist country where life was tightly controlled. The government censored newspapers and books. Secret police watched people and made them afraid to speak their true thoughts. People in the streets did not have honest discussions about politics. The schools taught only what the communist party wanted taught. Freedom of speech and thought were not permitted.

In January 1968, a new leader took over the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. His name was Alexander Dubček. He believed that communism did not have to be cruel and rigid. He thought the system could be improved, made fairer, and made more humane, while remaining communist. He called his idea "socialism with a human face." What he meant was simple: keep the basic communist structure, but allow people to speak more freely, the media to be more honest, and to debate the country's future.

When Dubček took power, something amazing happened. The government immediately loosened censorship. Newspapers began printing real news and honest opinions rather than just propaganda. Radio and television became more interesting and more truthful. People began to talk openly in cafes and streets about what they wanted the country to become. Older people could finally speak about the terrible things they had experienced in the 1950s, when the communist government had killed many innocent people in brutal show trials. Younger people could dream about a different future.

For a few months, from spring into summer 1968, Czechoslovakia felt like a completely different country. It was like someone had suddenly turned on the lights after decades of darkness. This period is called the Prague Spring. The word "spring" means that after a long, cold winter, a warm and hopeful spring has arrived. That is what people felt—that hope was on the way. But the spring would be very short.

WHAT WAS THE PRAGUE SPRING?

Dubček's reforms did not challenge the basic idea of communism. He did not say the country should join NATO or become capitalist. He did not tell people to have multiple political parties or that the Soviet Union should have no say in Czechoslovak affairs. What he said was that communism could be more democratic, more open, and more responsive to people's needs.

The reforms included allowing newspapers more freedom to publish real news. It meant allowing radio and television to discuss serious topics, not just propaganda. It meant that people could have political discussions without fear. It meant that the government would listen to suggestions from workers, students, and ordinary people about how to improve the economy. Dubček believed that a more open, more honest communism would be more substantial and more legitimate, because people would support it willingly rather than out of fear.

Czechoslovak society responded to this opening with extraordinary energy. Newspapers became fascinating to read. Writers began to publish stories and essays that had been forbidden before. Philosophers and economists gave lectures about new ideas. Students organized discussions about history, politics, and philosophy. Workers' meetings became genuine forums for debate, not just rubber-stamp exercises. Ordinary citizens filled cafes and streets to argue and discuss what a better Czechoslovakia might look like. Intellectuals felt they could finally use their minds freely. Young people thought that the future might be different from the past.

A historian later described this explosion of public speech and writing as a "media orgy"—meaning that the whole society was talking, writing, and broadcasting constantly, almost in a frenzy of released expression. After decades of silence and fear, people could finally say what they thought. It was exhilarating, and for a time it seemed as if the country was waking from a very long sleep.

THE SOVIET UNION BECOMES ALARMED

While the Czechoslovak people were celebrating their new freedom, the leaders of the Soviet Union were becoming very worried. The Soviet leaders understood that what was happening in Czechoslovakia could inspire similar movements in other countries that were under Soviet control. Poland, Hungary, East Germany, and Bulgaria—all of these countries had populations that wanted more freedom. If the Soviet Union allowed Czechoslovakia to liberalize, people in these other countries might ask: "Why can't we have the same freedoms? Why can't we have the same kind of open media and honest discussions?"

The Soviet leaders also worried that Czechoslovakia might start to move away from Soviet control. Although Dubček promised loyalty to the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet alliance, the Soviets were unsure they could trust him. Once Czechoslovaks tasted freedom and openness, might they want to become more independent, like Yugoslavia and Romania, which were communist but not completely under Soviet control? Czechoslovakia was geographically in the heart of Eastern Europe. If it slipped out of Soviet control, it could become a bridge between Eastern and Western Europe, threatening Soviet power.

The Soviet leadership sent warnings to Dubček. They told him to tighten censorship, remove reformers from the government, and stop allowing such open discussion. They said the changes were dangerous to the whole communist bloc. Dubček tried to convince Moscow that he was still loyal, still communist, and still committed to the Soviet alliance. But the Soviet leaders did not believe him. In their view, the Prague Spring had already gone too far. The only way to stop it was to send in a military force.

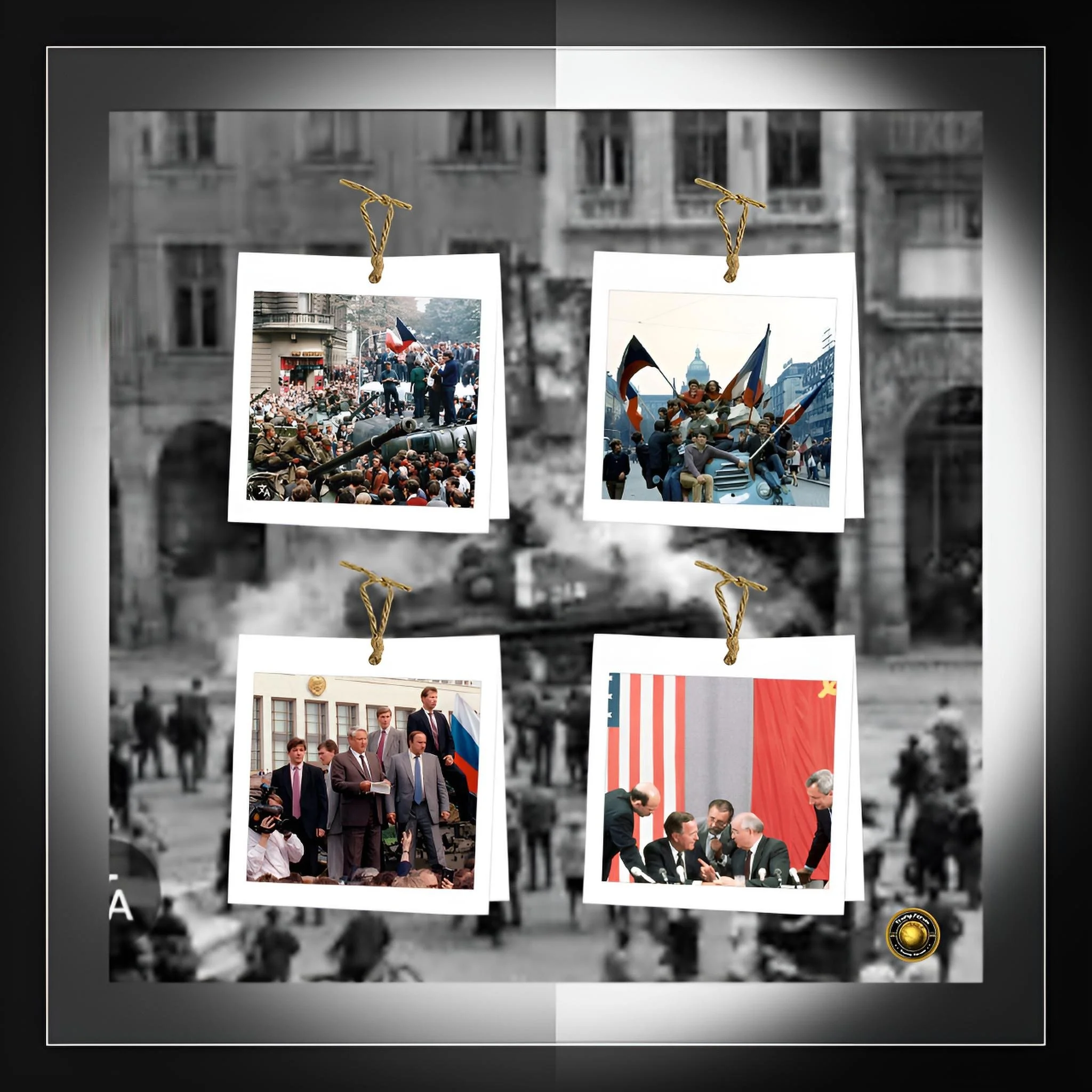

THE TANKS ARRIVE: AUGUST 20-21, 1968

On the night of August 20th and early morning of August 21st, 1968, an enormous number of tanks and soldiers crossed the border into Czechoslovakia. About half a million troops from the Soviet Union and allied countries invaded. They occupied cities, took over government buildings, and arrested Dubček and other leaders who wanted reform. It was one of the most significant military invasions Europe had seen since World War II.

But because Czechoslovak military forces had been ordered not to fight back, no major battles or armies clashed. Instead, the invasion mainly involved tanks and soldiers moving into cities that could not resist. What did happen was that ordinary people showed great courage. They stood in front of tanks, trying to block them with their bodies. They removed street signs and painted over them so soldiers would get lost. They argued face-to-face with soldiers, trying to explain that they were not enemies of communism, that they just wanted freedom and honesty.

Radio stations and television broadcasters continued broadcasting from hidden locations, telling people what was happening, calling for calm, and reminding the population not to give up hope. Czechoslovak radio became the voice of the resistance, broadcasting the truth about what was happening, keeping people informed, and maintaining a sense of unity in facing the occupation.

But ultimately, the massive military force was too great. The Czechoslovak people could show courage and resist, but they could not stop tanks with their bare hands. Within days, the occupation was complete. The Soviet Union had successfully crushed the Prague Spring.

THE BREZHNEV DOCTRINE: EXPLAINING WHY THE INVASION WAS ACCEPTABLE

After the invasion, the Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev explained to the world why the Soviet Union had the right to invade Czechoslovakia. He said something that became famous as the Brezhnev Doctrine. He said that while each communist country had some independence, the interests of all communist countries together were more important than the independence of any single country. He said that if a communist country started to move away from true communism and toward capitalism or Western influence, the Soviet Union and its communist allies had a duty to stop it, even by using military force. He called this "socialist internationalism."

In plain language, the Brezhnev Doctrine meant: you communist countries are not really independent. You are part of a Soviet-controlled bloc. You can only be independent if you do what we tell you to do. If you try to go a different direction, we will stop you by force.

This was an essential and dangerous new rule. It said that smaller countries had limited sovereignty—limited freedom to make their own choices. It meant that the Soviet Union gave itself the right to invade any of its neighboring countries if it felt those countries were not being communist "correctly."

WHAT THE SOVIET UNION LEARNED FROM THE PRAGUE SPRING

The Soviet leadership took several vital lessons from the Prague Spring. These lessons shaped how they acted for decades, and they still influence how Russia acts today.

First lesson: The Soviets learned that they could use military force to stop reform movements, and the West would not go to war over it. The United States and its allies protested at the United Nations. Newspapers criticized the invasion. But no Western army came to help Czechoslovakia. No missiles flew. No direct fighting happened between Soviet and Western troops. The Soviet leaders realized that the West saw Czechoslovakia as being in the Soviet sphere—an area where the Soviet Union could act as it wanted without risking a big war with the West.

Second lesson: The Soviets learned that you have to control the media and public speech. The Prague Spring had become strong partly because newspapers and radio had become free to report the truth and broadcast discussions. The Soviets realized that if they kept tight control over what people could say and what the media could print, it would be harder for reform movements to develop. This is why the Soviet Union, after 1968, kept rigorous control over television, newspapers, and radio.

Third lesson: The Soviets learned that if you are an immense power and a smaller neighbor starts to change its political system or move toward your enemies, you should stop it early with military force. Do not wait and hope it will change on its own. Do not hope that the person in charge will keep their loyalty. Just send in tanks and crush it.

Fourth lesson: The Soviets learned that words of protest from the rest of the world are less important than control over their sphere of influence. The world was angry. Newspapers everywhere criticized the Soviet Union. But the Soviet Union kept Czechoslovakia anyway. This taught the lesson: international anger matters less than having power and control.

WHY DOES PRAGUE SPRING MATTER IN 2026?

Understanding what happened in Prague in 1968 is crucial to understanding world events in 2026. Here is why.

Today's Russia still thinks as the Soviet Union did in 1968. Russia looks at Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, and Moldova as countries that should be under Russian influence or Russian control. When Ukraine tried to become more democratic and more Western-oriented, Russia saw this as a threat, just like the Soviet Union saw the Prague Spring as a threat. Russia believed it had the right to stop Ukraine from making this choice. In 2014, Russia took the region called Crimea from Ukraine. In 2022, Russia invaded the whole country.

Russia acts today as if smaller countries do not have complete freedom to choose their own path. Russia says that Ukraine and other neighbors should not join NATO or the European Union. Russia uses military force and the threat of military force to try to make neighbors obey. This is precisely like the Brezhnev Doctrine: it is saying that smaller countries' independence is limited by what Russia wants.

Also like the Soviet Union after 1968, today's Russia keeps very tight control over the media and what people can say. The Russian government does not allow a free press. It controls what television and newspapers print. It punishes people who criticize the government. It seems that Russia learned the lesson from Prague that managing information is necessary to prevent resistance to its power.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR COUNTRIES NEAR RUSSIA?

For countries in Central and Eastern Europe that remember the Soviet Union and the Prague Spring, the memory is very personal.

The Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and the Baltic countries all lived under Soviet control.

They remember what it was like to have their freedom taken away. They remember that when the Soviet Union wanted to do something, other countries' protests did not stop it.

These countries have been influential supporters of Ukraine since Russia invaded in 2022. They push for more weapons, more help, and stronger sanctions against Russia.

They do this partly because they remember Prague—they do not want to see Ukraine treated the way Czechoslovakia was treated. They have said: "We were once like Prague. We know what it feels like to be crushed by a big neighbor. We will not let it happen again if we can help it."

WHAT DOES PRAGUE SPRING TEACH US ABOUT THE FUTURE?

The Prague Spring teaches us several hard truths. First, it shows that great powers will sometimes use military force to control smaller neighbors, and the rest of the world's disapproval alone will not always stop them. Second, it shows that if a small country wants to change its political system and move toward the West, it needs strong protection from powerful allies. Without that protection, a threatened neighboring great power may invade.

Third, it teaches that freedom and hope can suddenly be crushed if the people who enjoy them lack the military power to defend them. The Czech and Slovak people showed tremendous courage and unity during the Prague Spring, but when the tanks came, courage alone could not stop them. They needed military support, but they did not have it.

CONCLUSION: HISTORY IS NOT OVER

The tanks that rolled into Prague in August 1968 are long gone. The Prague Spring lasted only about eight months. But the memory of what happened in Prague has lasted for decades, and it remains crucial to how we understand the world in 2026.

The Prague Spring reminds us that history is not finished. It shows that great powers still believe they have the right to control their neighbors. It shows that military force remains a way that big countries enforce their will. It shows that the world watching and caring is not always enough to protect smaller nations.

But the Prague Spring also reminds us of something hopeful: people will keep trying to be free, to speak honestly, and to choose their own future, even in the face of overwhelming force. The Czechoslovak people in 1968 showed extraordinary courage. They may not have won their freedom at that moment, but they showed that freedom is what people want. And eventually, after the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s, Czechoslovakia did become free and democratic.

They are still important. We must remember what happened in Prague.

We must understand why small countries cannot always protect themselves. And we must decide whether the world will allow great powers to determine the fate of smaller nations, or whether we will work to build a system in which smaller countries can truly be free to choose their own futures.

The world is still watching. The question, as it was in 1968, is whether watching will be enough.