Greenland, Tanks, and History: What the Soviet Union Teaches Trump About Power

Summary

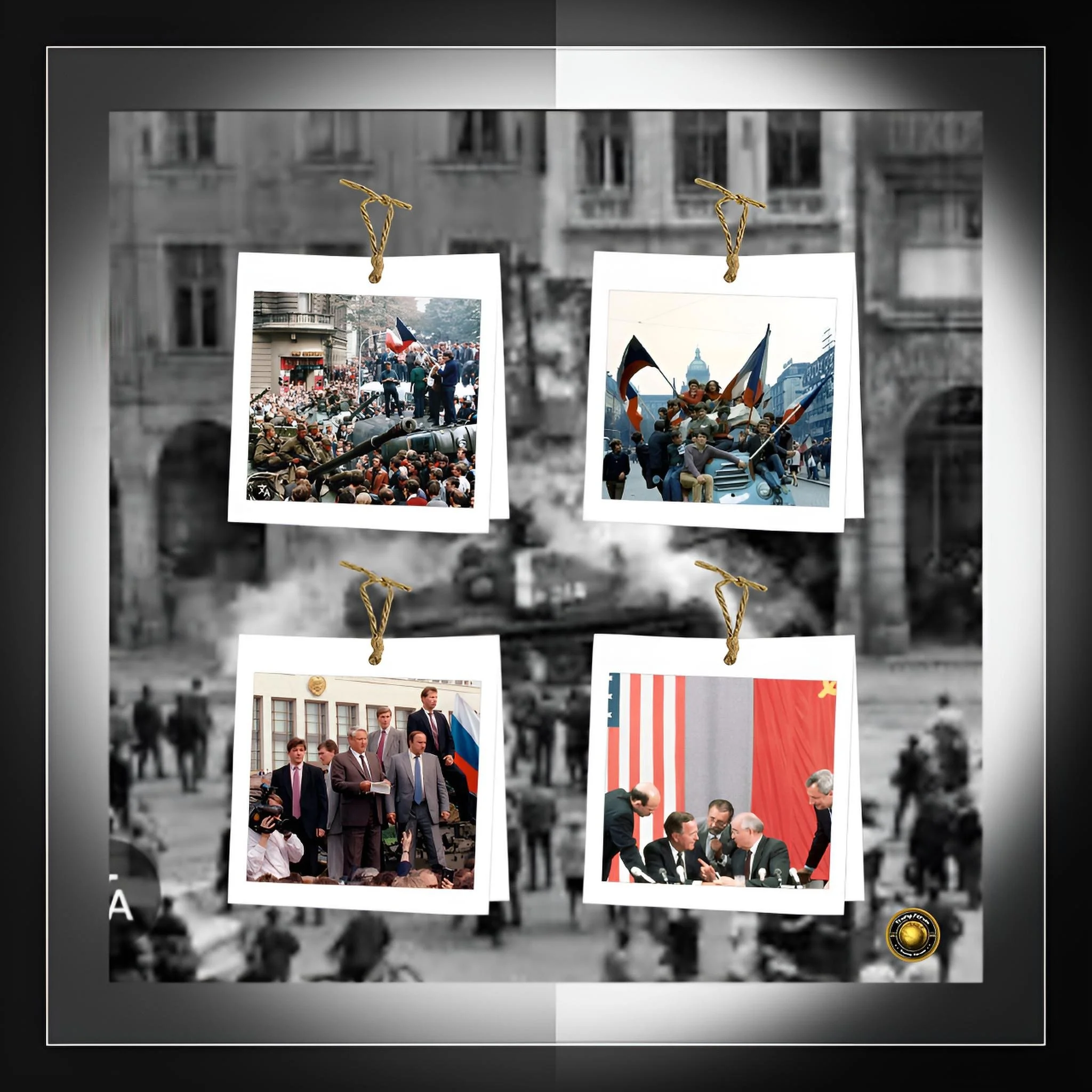

What Happened in 1968 That Matters Today? A Historical Parallel Worth Understanding

In August 1968, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev made a crucial decision. He sent 500,000 troops from the Soviet Union and allied communist countries to invade Czechoslovakia.

The reason was simple: the Czech government, led by a reformer named Alexander Dubček, had started allowing more personal freedom and democratic discussion. Soviet leaders panicked.

They believed that if Czechs could have freedom, citizens in other communist countries might demand the same thing. So they invaded.

The military operation succeeded. Soviet troops occupied Czechoslovakia, arrested the reform leaders, and shut down the reform movement.

From a military perspective, it looked like a victory.

But here is the crucial point that historian now emphasize: This military victory turned into a strategic defeat that lasted decades.

Twenty years later, in 1989, the people of Czechoslovakia rose up again in what became known as the Velvet Revolution. This time they succeeded in ending communist rule completely.

The 1968 invasion had planted seeds of resentment that grew for two decades until they finally bloomed into successful revolution.

The invasion showed Czechoslovak citizens that Soviet power ultimately depended on military force and fear, not on genuine authority or legitimacy. Once people understood this, they could never again view Soviet communism as inevitable or legitimate.

Now, in 2026, President Donald Trump has begun a campaign to acquire Greenland. At first, he demanded that Denmark sell him Greenland. Then he threatened military seizure. Then he imposed economic tariffs against European nations that opposed the sale. Finally, by late January 2026, he shifted toward negotiating "framework agreements" for American military access.

The parallels to the Soviet experience are striking. Just as Soviet leaders tried to force their will on a resistant population through military and political pressure, Trump attempted to force American acquisition through threats of military action and economic coercion. And just as the Soviets discovered, coercive pressure against determined populations and allied nations produces the opposite of intended results.

Why Did the Soviet Union Invade Czechoslovakia?

Understanding the Historical Context

To understand why this history matters for today's Greenland situation, we need to understand what happened in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s. After World War II, the Soviet Union took control of Eastern Europe, including Czechoslovakia.

For nearly two decades, the Soviet Union imposed strict communist rule. Citizens had no freedom of speech or press. The government controlled all businesses and made all economic decisions. People could not travel freely or choose their own professions. Life was highly controlled and often miserable.

In the 1960s, however, reform movements began emerging throughout Eastern Europe. The Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had given a famous speech in 1956 attacking the brutal dictator Stalin. This speech opened the door for people to think that communism might be reformed and made less oppressive. In Czechoslovakia, intellectuals, students, workers, and even some communist party members began pushing for change.

By 1968, a man named Alexander Dubček became the leader of the Czech Communist Party. Dubček was not a rebel trying to overthrow communism. Rather, he believed communism could be reformed and made better. He wanted to give Czechs more freedom to speak, more freedom for the media to publish, and some economic reforms. He called this "socialism with a human face"—meaning communism that was less brutal and more humane.

The Prague Spring, as this period became known, inspired enormous hope among Czechs and Slovaks. Citizens felt like their country might finally change. Newspapers began publishing critical articles. Young people organized discussions about freedom. Workers talked about improving working conditions. The atmosphere in Prague became electric with the possibility of change.

But Soviet leaders became deeply frightened. Brezhnev and his advisers feared that if Czechoslovakia experienced liberalization, other communist countries in Eastern Europe would demand the same. Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, and East Germany might all rebel against Soviet control. Worse, they feared that a free Czechoslovakia might eventually leave the Warsaw Pact (the Soviet-led military alliance) and even join NATO (the American-led alliance). Soviet leaders could not tolerate this possibility.

At first, Brezhnev tried negotiation. Soviet and Czechoslovak leaders met at Cierna and Bratislava, trying to find compromise. Dubček appeared to accept Soviet constraints on how far liberalization could go. But the problem was that once Czechs had tasted a bit of freedom, they wanted more. Dubček could not control the reform movement even if he wanted to. The population pushed for greater freedom than Dubček or Brezhnev had agreed upon.

Soviet hardliners, including conservative Czech communist leaders, convinced Brezhnev that negotiation would not work. Dubček could not be trusted to constrain the reforms. Military action was necessary.

On the night of August 20-21, 1968, without asking permission from the Czech government or inviting the invasion, Soviet tanks rolled across the border. Troops poured into Prague and other cities. The invasion forces arrested Dubček and other leaders. Within hours, Soviet military power had overcome all Czechoslovak resistance.

What Did the Soviet Invasion Accomplish?

Immediate Military Success and Long-Term Political Failure

The invasion achieved exactly what the Soviet military planners intended. Soviet troops occupied the entire country. Czechoslovak armed forces, which were weak and poorly equipped, could not resist. Czechoslovak leaders negotiated a surrender in what became known as the Moscow Protocol.

They agreed to reverse the reforms. Soviet troops would remain in Czechoslovakia to ensure Soviet control. Hardline communist leaders replaced Dubček. A period called "normalization" followed, during which the secret police suppressed dissent and arrested protesters.

By any military measurement, the invasion was a triumph. Five hundred thousand troops overwhelmed a much smaller opponent. The country was occupied. Soviet authority was restored. The reform movement was crushed.

However, something else happened that Soviet leaders had not anticipated. The invasion revealed a crucial truth about Soviet power: It depended entirely on military force and fear. Soviet communism did not actually have the support or loyalty of the Czech population.

The Czechs had not freely chosen Soviet rule. They had not happily accepted communist ideology. Soviet power existed only because Soviet tanks were pointed at them. This lesson sank deeply into the consciousness of every Eastern European population.

Over the following two decades, Czechoslovak society became psychologically alienated from Soviet communism. Surveys showed that young Czechs and Slovaks had no faith in communist ideology. Intellectuals who had hoped for reform became cynics. Workers lost faith in the system. Families retreated into private life, caring for their own households but showing no loyalty to communist institutions.

More importantly, the invasion demonstrated to every Eastern European nation that Soviet power, while militarily supreme, was ultimately fragile and depended on continuous violence.

If communism truly provided a superior system that citizens willingly supported, why was military occupation necessary?

Why were tanks needed?

The answer implied that communist rule was not legitimate in the eyes of the people and could be maintained only through coercion.

This memory remained encoded in the consciousness of Czech, Polish, Hungarian, and other Eastern European populations. In 1989, when Mikhail Gorbachev signaled that the Soviet Union would no longer intervene militarily in Eastern Europe, all these nations moved simultaneously to overthrow communist rule.

The Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia succeeded within weeks because the psychological groundwork had been prepared by the 1968 invasion. People remembered that Soviet power was fragile, dependent on military force, and ultimately unsustainable against determined resistance.

Trump's Greenland Campaign

A Parallel Story of Coercive Pressure and Resistance

Now let us examine Trump's campaign to acquire Greenland, which began in late 2024 and continues through January 2026. The parallels are striking. Like the Soviet leaders who believed their military superiority would enable them to dictate terms, Trump assumed that American military and economic power would ultimately compel Denmark and Greenland to accept American acquisition.

Trump's campaign began with assertions of inevitability. He declared, "One way or the other, we are going to have Greenland." He suggested that American power and resources would eventually overcome any resistance. He claimed that America's ability to purchase or seize the territory was simply a matter of willpower and time. He criticized Denmark for possessing Greenland, arguing that historical claims from "five hundred years ago" gave Denmark no right to the island. His rhetoric suggested that American power would ultimately prevail regardless of what Greenlanders or Danes wanted.

The Trump administration's motivations resembled Soviet fears about losing control. Trump and his advisers believed that failing to control Greenland would result in Chinese or Russian dominance. They argued that China might seize Greenlandic rare earth minerals. They claimed that Russia might establish military bases on the island. These threats were exaggerated or unfounded, but they created a sense of strategic urgency justifying American acquisition.

Trump emphasized the strategic location of Greenland, sitting between North America and Europe, positioned in the Arctic where new shipping routes are opening as ice melts. He noted that Greenland possesses rare earth minerals essential for batteries, military equipment, and electronics. These are legitimate strategic concerns, but Trump presented them as justifying full American sovereignty acquisition rather than cooperative arrangements.

The Trump administration's initial approach mirrored the Soviet playbook: Assert military and economic superiority, make demands without negotiation, expect compliance through intimidation. Danish and Greenlandic leaders were expected to realize that they could not resist American power and would therefore surrender voluntarily.

What Happened When Trump Applied Pressure?

The Response Surprised Him

But something unexpected happened. Instead of capitulating, Denmark and Greenland unified in resistance. Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen visited Greenland in a highly publicized gesture of solidarity. She declared that "sovereignty is not for negotiation" and reminded Trump that Denmark had been America's loyal ally for decades. She refused to be intimidated.

Leaders from across Europe—France, Germany, Poland, Britain, Spain, and others—issued a joint statement declaring that Greenland "belongs to its people" and that decisions about Greenland's future must be made by Greenlanders themselves, not by external powers. Conservative European leaders who might have been expected to accommodate American demands publicly supported Denmark.

Greenlandic public opinion remained firmly opposed to American acquisition. Opinion polls showed that eighty-five percent of Greenlanders opposed annexation to the United States. The Greenlandic government, which had campaigned on pursuing independence from Denmark, would not accept a shift to American rule.

When Trump announced ten percent tariffs on Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, French, German, British, Dutch, and Finnish exports, expecting this to break resistance, the opposite happened.

Europeans saw this not as intimidation to be surrendered to but as evidence that Trump was willing to harm NATO allies for his own purposes. This accelerated European discussions about reducing dependence on American military protection and developing independent European defense capabilities.

The more pressure Trump applied, the more unified the resistance became. The economic threat against NATO allies actually strengthened European cohesion rather than fracturing it. The implied military threat against Greenland strengthened rather than weakened NATO's commitment to defending Danish sovereignty. Exactly as with the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, coercive pressure generated the opposite of intended results.

What Does This Parallel Tell Us?

The Limits of Coercive Power in the Modern World

The fundamental similarity between the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and Trump's Greenland campaign is that both reflect attempts by powerful nations to employ military or economic coercion to force resistant populations and allied governments to accept outcomes those populations and governments have clearly rejected.

The Soviet Union, despite enormous military superiority, could occupy Czechoslovakia only through military force. Once the occupation occurred, the Soviets discovered they could not transform occupation into legitimacy. They could not persuade Czechs to willingly support Soviet rule. They could suppress dissent temporarily, but they could not prevent the psychological alienation that would ultimately enable the Velvet Revolution.

Similarly, Trump's administration discovered that American military and economic power, while overwhelming in raw capability, could not compel Denmark or Greenland to surrender sovereignty. Military capability to seize Greenland proved irrelevant given NATO alliance structures and international legal norms that make annexation diplomatically catastrophic. Economic threats against allies produced unified European resistance rather than fragmentation.

The core insight is this: In modern international systems characterized by alliances, international law, and economic interdependence, coercive power proves ineffective for compelling territorial acquisition or hegemonic expansion. Military superiority alone cannot achieve political objectives that determined populations and allied governments oppose.

Each application of coercive pressure reveals the limitations of raw power and generates resistance that ultimately undermines hegemonic authority. This was the Soviet lesson from Czechoslovakia, and it is becoming the American lesson from Greenland.

How Did Trump's Campaign End?

The Shift Toward Negotiation

By late January 2026, Trump's strategy had fundamentally shifted. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Trump announced that he and NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte had negotiated a "framework for a future deal" regarding Greenland and Arctic security. Trump simultaneously withdrew his threats of military action and his tariff announcements.

The new framework appears to involve American military access and enhanced Arctic security cooperation with Greenland and Denmark, achieved through negotiated agreement rather than conquest. Trump announced that America was "getting everything we want at no cost," suggesting that the framework would provide American strategic objectives without requiring sovereignty acquisition.

However, fundamental questions remain unresolved. The exact dimensions of American military access remain negotiated. Denmark and Greenland continue insisting that sovereignty cannot be transferred. Greenland remains committed to eventual independence from Denmark rather than absorption into another power's rule.

The shift from coercive demands to negotiated frameworks represents a recognition that coercion does not work. But whether this recognition will prove sustained or merely temporary remains uncertain. Trump's rhetoric continues to oscillate between acquisition language and cooperative security frameworks.

What Happens Next?

The Path Forward and What History Suggests

The Davos framework presumably establishes the trajectory for future negotiations. American military presence in Greenland may expand through negotiated base agreements. American participation in Arctic resource development through private companies may increase. NATO collective Arctic security cooperation may strengthen.

However, successful implementation requires what coercive approaches systematically fail to deliver: genuine respect for Greenlandic and Danish sovereignty, recognition of Greenlandic aspirations for independence, and American commitment to collaborative rather than dominative frameworks.

European engagement with the framework has been cautious. NATO allies have acknowledged shared Arctic security interests but have simultaneously begun developing parallel European Arctic strategies. The European Union's December 2025 decision to grant a thirty-year exploitation license for graphite mining to a European company suggests that Europeans intend to pursue independent Arctic policies rather than deferring to American leadership.

History suggests that coercive initiatives against determined populations and allied governments generate consequences opposite to those intended. The Soviet Union learned this too late, after two decades of occupation that ultimately proved unsustainable. The question for the Trump administration is whether it will absorb this lesson quickly or whether continued application of coercive pressure will further accelerate the erosion of American alliance relationships and strategic influence.

Conclusion

What the Soviet Experience Teaches About American Power Today

The story of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia and the subsequent Velvet Revolution offers a crucial lesson for understanding contemporary American strategy regarding Greenland. Military and economic superiority, while providing short-term tactical advantages, prove strategically ineffective when deployed against determined populations and alliance partners within integrated international systems.

The Soviet Union possessed overwhelming military power but discovered that this power could maintain occupation only through permanent garrison forces and permanent repression. The invasion revealed Soviet hegemony as dependent on force rather than legitimate authority. This revelation, while tactically reversible temporarily, strategically undermined Soviet communism for two decades until it finally collapsed entirely in 1989.

Trump's Greenland campaign demonstrates analogous dynamics. Coercive pressure against NATO allies produced unified resistance rather than compliance. Threats of military seizure proved ineffectual given alliance structures and international law. Economic threats against allies generated European discussions about strategic autonomy—outcomes that reduce rather than enhance American hegemonic authority.

The Soviet Union learned its crucial lesson through the Czechoslovak experience: that power exercised through coercion against resistant populations and allied governments ultimately erodes rather than reinforces hegemonic authority. Whether the Trump administration absorbs this lesson through the Greenland episode or continues pursuing coercive strategies remains to be seen.

What seems evident is that the historical trajectory of declining superpowers follows a predictable pattern. They attempt to compensate for underlying decline through displays of military and economic force against targets perceived as vulnerable. But these displays, rather than reversing decline, accelerate it by demonstrating the brittleness of hegemonic authority and accelerating the search by other powers for alternative partnerships and strategic autonomy.

The Soviet experience suggests that superpowers confronting genuine strategic challenges would do far better to invest in alliance relationships, collaborative frameworks, and mechanisms for generating voluntary compliance rather than attempting to compel submission through coercion.

Whether great powers absorb this lesson before historical circumstances force that learning proves to be the recurring question of international politics.