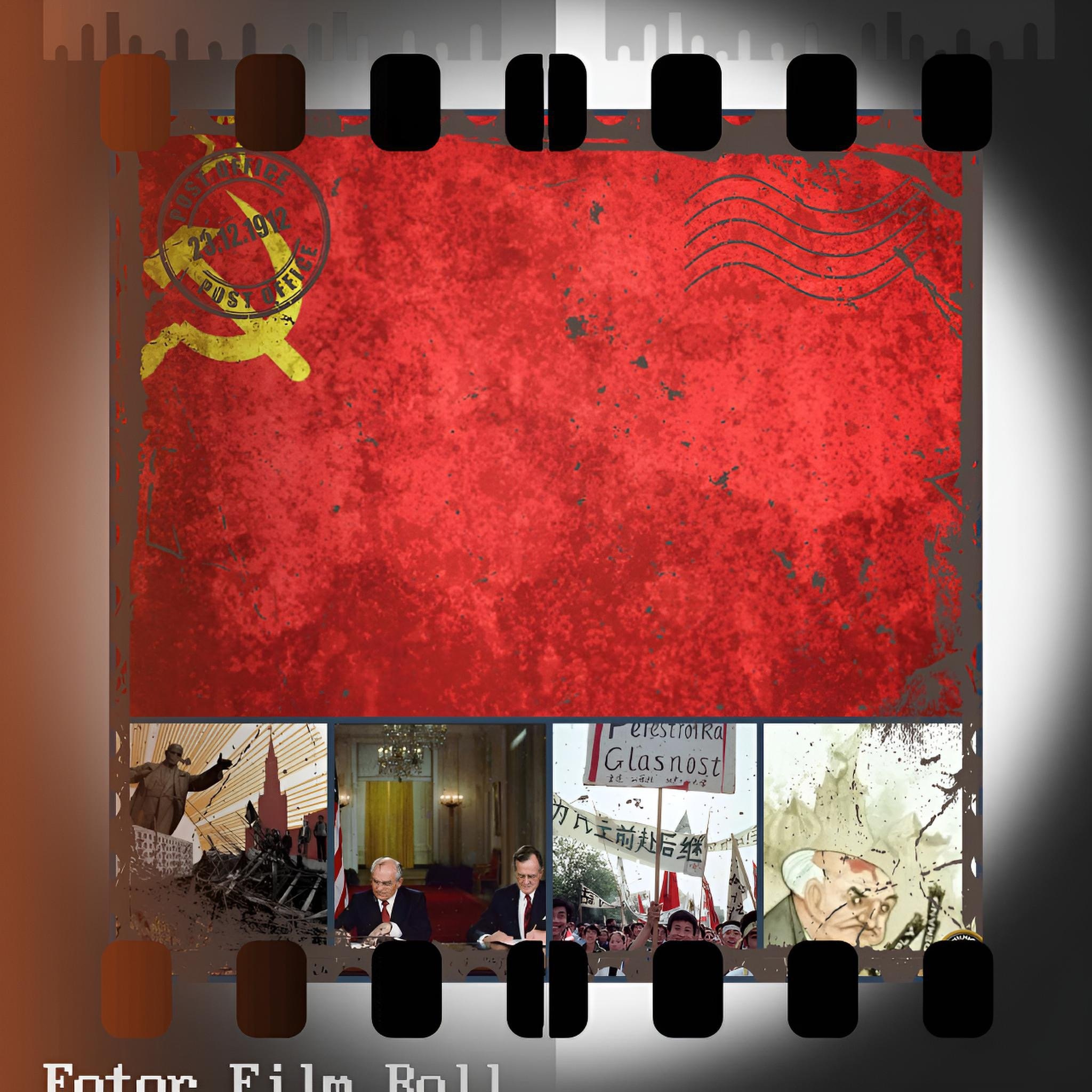

From the Ashes of Communism: The Rise of a Corrupt, Nihilistic, and Warmongering Elite

Introduction

The Collapse of the Communist Dream

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the Soviet Union dissolved barely two years later, many hailed it as the “end of history.”

Western intellectuals such as Francis Fukuyama suggested liberal democracy and capitalism had triumphed as the ultimate forms of human governance. Yet, beneath the surface celebration of freedom and market reform, something darker was stirring in the ruins of the communist world.

Communism, for all its failings, had been an ideological system premised—at least rhetorically—on moral promises: equality, fraternity, collective welfare, and international solidarity. The Soviet narrative, though deeply flawed and often violently enforced, gave people a sense of participation in a grand historical mission.

When that mission collapsed, it left behind not only a political void but a profound moral one. Out of that vacuum, new powerbrokers arose—unconstrained by ideology, unburdened by morality, and driven by sheer ambition, greed, and the hunger for dominance.

In the 1990s, countries across Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the former Soviet republics underwent “shock therapy” economic reforms: rapid privatization, liberalization, and deregulation, advised largely by Western economists.

The intent was to transform centrally planned economies into market-driven democracies. The outcome, however, was an orgy of asset stripping, corruption, and organized crime. State enterprises—built over decades through collective labor—were sold off for pennies to well-connected insiders.

Overnight, a new class of oligarchs emerged, controlling vast swaths of national wealth while ordinary citizens plunged into poverty.

In Russia, Ukraine, and beyond, the collapse of the communist order did not herald the birth of democracy—it produced kleptocracy.

The Rise of the Oligarchs

The new elites of the post-communist world were not revolutionaries or reformers; they were opportunists. Many had backgrounds in the Communist Party, the KGB, or state industrial management. They understood power not as a tool for collective advancement, but as an instrument for personal enrichment.

In Russia, the privatization of the 1990s allowed a tiny number of individuals—such as Boris Berezovsky, Roman Abramovich, and Mikhail Khodorkovsky—to acquire ownership of national resources like oil, gas, and metals. They did so through rigged auctions, insider networks, and the manipulation of weak state institutions.

By 1996, these oligarchs wielded more influence than the government itself, bankrolling political campaigns and shaping policy to ensure their privileges remained untouched.

In Ukraine, similar dynamics prevailed. Former Communist apparatchiks transformed themselves into businessmen and political powerbrokers, entrenching corruption as a fundamental feature of the state. In Central Asia, authoritarian rulers like Nursultan Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan and Islam Karimov in Uzbekistan built personal fiefdoms, suppressing dissent while enriching family members and loyalists.

The ideology that replaced communism was not capitalism in its moral or civic sense—it was a kind of nihilistic materialism. The old collectivist ethos was gone, replaced by a belief in money as the only source of meaning and authority. “Success” became synonymous with wealth and power, not production or innovation.

This new elite class was both post-ideological and post-moral: they no longer pretended to serve a cause beyond themselves.

The Moral Vacuum: From Ideology to Nihilism

The end of the Soviet era was not only a political event but a metaphysical rupture. Millions had built their lives around the belief that they were part of a universal struggle against exploitation and injustice. When that myth collapsed, it was replaced not by a renewed humanism, but by cynicism and despair.

The generation that came of age in the 1990s lived amidst economic chaos, collapsing institutions, and rising criminality. The social safety nets of the communist system—housing guarantees, free education, stable employment—disappeared almost overnight. In their place came deep inequality, consumerism, and the pervasive sense that rules no longer applied. Under such conditions, nihilism became the default philosophy of survival.

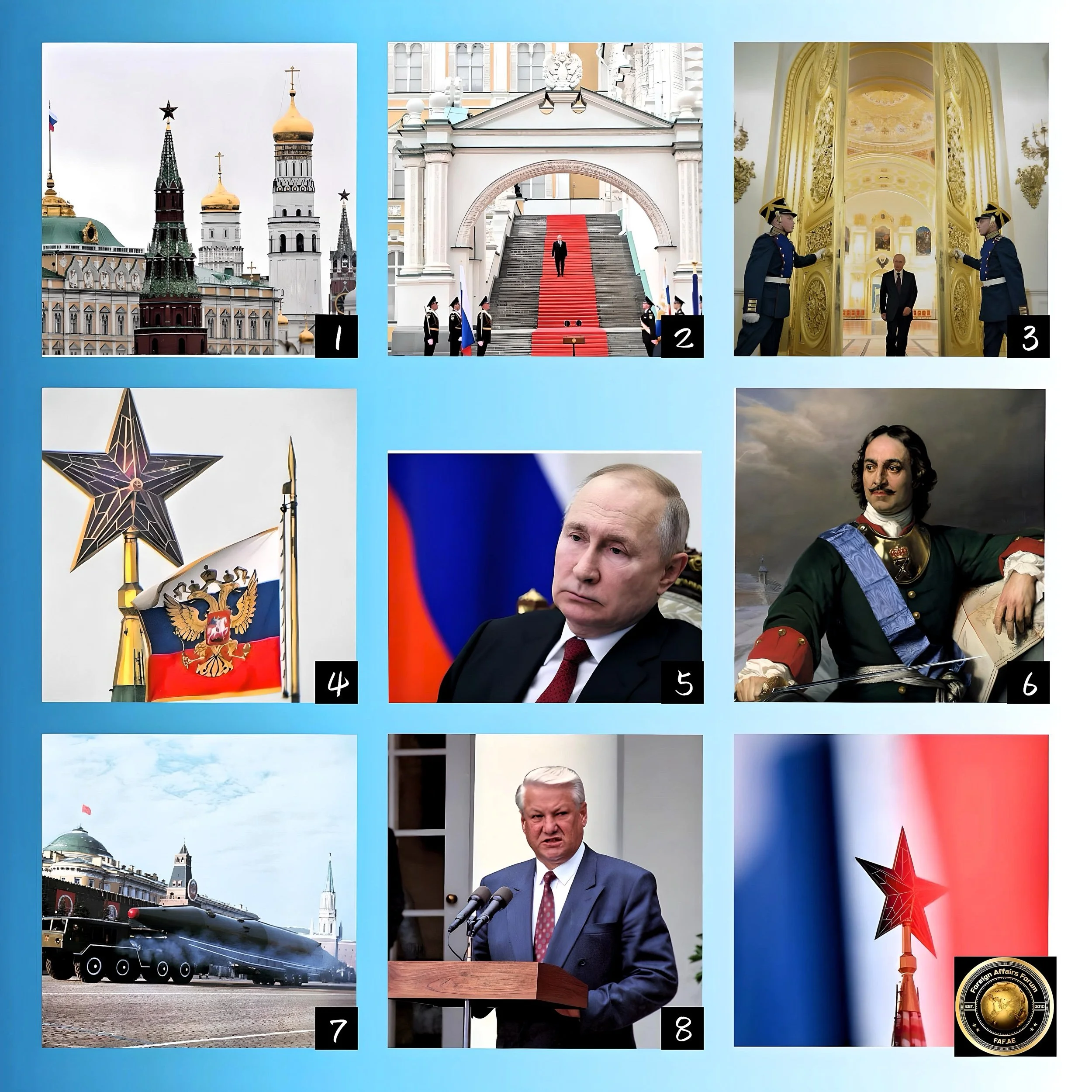

This nihilism wasn’t merely personal; it infected political culture. In Russia, as Vladimir Putin rose through the ranks of the post-Soviet security establishment, he grasped the essential truth of this cultural vacuum: people no longer believed in anything except strength.

Putin built his regime on that insight, promising not freedom or justice, but stability and pride. He restored the symbols of empire and replaced the Marxist-Leninist dream with a neo-imperial one, sanctified by nationalism and Russian Orthodoxy. The moral reckoning that might have followed communism’s crimes was buried under nostalgia and authoritarianism.

The Western Role: Hubris and Miscalculation

Western policymakers misread the 1990s. They viewed post-Soviet transitions through the lens of neoliberal triumphalism, assuming that market reforms would spontaneously produce democracy and civil society. But they underestimated how fragile institutions were in post-communist states. Without strong courts, transparent governance, or a culture of accountability, privatization simply handed public assets to the most ruthless.

International financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank demanded austerity and rapid liberalization that crippled social services. Western corporations, meanwhile, exploited the chaos to secure lucrative deals in energy and raw materials.

In Russia, Western consultants helped design the notorious “loans-for-shares” schemes that concentrated wealth in the hands of a few. The West, in effect, midwifed the rise of the very kleptocratic elite that would later turn openly hostile.

For the emerging elites of the post-communist world, Western hypocrisy became both a shield and an inspiration. They saw Western economies dominated by corporate lobbies, media manipulation, and offshore finance.

They concluded—accurately or not—that corruption was simply the universal language of power. The promise of Western democracy rang hollow amid NATO’s expansion, economic inequality, and the moral bankruptcy of the global financial crisis that followed.

Power Without Purpose: The New Authoritarianism

If communism sought to transform humanity, the new post-communist authoritarianism seeks only to control it. Its ruling class possesses no ideology beyond self-preservation, no vision beyond maintaining order and extracting profit. Yet that very absence of conviction grants these regimes flexibility—they can justify repression as patriotism, militarism as defense, and censorship as stability.

In Putin’s Russia, the state reasserted control over strategic industries under the pretext of national security, while the oligarchs were forced into submission or exile.

The Kremlin’s new compact was simple: loyalty in exchange for impunity. This system of “controlled corruption” allowed a centralized elite to maintain the appearance of legality while enriching itself massively from energy rents and state contracts.

But corruption has consequences beyond economics—it corrodes institutions, breeds paranoia, and fosters aggression. As domestic legitimacy weakens, regimes driven by such elites turn outward, seeking validation and distraction through conflict. War becomes both a political tool and a moral narcotic.

War as Salvation: The Turn to Militarism

The wars fought by post-communist regimes—from Chechnya to Georgia, from Crimea to the Donbas—are not ideological crusades but instruments of survival. They serve to rally public support, silence dissent, and reaffirm the myth of national greatness. In this sense, warmongering is not a symptom of strength but of existential insecurity.

Militarism offers the perfect antidote to nihilism. Where corruption erodes belief in the state, war restores a sense of collective purpose. Where ideology has failed, nationalism provides meaning. The same elites who looted their nations present themselves as patriots, defenders of civilization against imagined enemies—NATO conspiracies, Western decadence, or internal traitors.

This transformation is tragically circular: the system reproduces crisis to justify its existence. Economic failure fuels repression; repression fuels militarization; militarization demands new conquests or confrontations.

Each war becomes a temporary solution to the deeper moral void left by the death of communism. As long as power is concentrated in the hands of nihilistic elites, peace remains unsustainable because peace threatens to expose their emptiness.

The Globalization of Kleptocracy

The post-communist elites did not isolate themselves behind the new Iron Curtain—they globalized their wealth. Through offshore accounts, real estate in London or Dubai, and shell companies in tax havens, they integrated themselves into the bloodstream of international finance.

Western banks, law firms, and consultants facilitated this process, turning political theft into legitimate investment.

Yachts, mansions, and football clubs became symbols of status for ex-KGB operatives and former Soviet industrial managers. The moral distinction between East and West blurred as money flowed seamlessly between Moscow, Cyprus, and Manhattan.

This globalization of kleptocracy eroded democratic norms far beyond post-communist borders. It corrupted political systems in the West, distorted property markets, and fostered lobbying networks that served foreign autocracies.

The “transnational elite” that emerged after 1991 was united not by ideology but by shared cynicism and impunity.

From the ashes of communism indeed arose a new ruling class—one that spoke the language of capitalism but retained the psychology of authoritarianism: secrecy, brutality, and contempt for the weak.

The Erosion of Truth and Meaning

One of communism’s legacies was the manipulation of truth through propaganda; one of neoliberalism’s legacies has been the commodification of truth. In the post-communist world, both merged into a new form of informational nihilism.

In Putin’s Russia, truth became purely instrumental. State media no longer sought to convince people of specific narratives—it sought to exhaust their capacity for belief. When every version of reality seems equally false, only power feels real.

This is the essence of the post-modern autocracy: rule not by terror alone, but by confusion and fatigue.

This epistemic decay is both symptom and strategy of the post-communist elite. The same pattern appears, in milder forms, across other former socialist states: populism, conspiracy theories, the weaponization of nostalgia.

These phenomena reflect a society that has lost faith in reason and justice, where the only remaining moral principle is “everyone lies.”

Cultural Reflections: From Utopia to Despair

Art, literature, and cinema in post-communist societies mirrored this descent from utopia to nihilism. The socialist-realist optimism of earlier decades gave way to dark humor, existential fatigue, and moral ambiguity.

Directors like Aleksei Balabanov, whose films portrayed post-Soviet Russia as a wasteland of money and violence, captured the spirit of the age more accurately than any political analysis could.

Writers chronicled the absurdity of freedom without meaning—where capitalism brought not opportunity but humiliation, where every dream was for sale.

The “Russian soul” that once sought transcendence through suffering now found itself mired in consumerism, nationalism, and fear.

This cultural malaise was not unique to Russia; it echoed across Eastern Europe, where disillusionment with both socialism and capitalism fueled populist backlashes.

The Geopolitical Consequences

The corrupt and warmongering elite born from communism’s ashes has reshaped global power itself. Russia, no longer the ideological superpower of the Cold War, became a spoiler state—exporting instability rather than revolution.

Its military interventions in Georgia (2008), Ukraine (2014 and 2022), and Syria (2015) served to project strength while concealing domestic stagnation.

China, though formally communist, followed its own path of hybrid authoritarian capitalism, demonstrating that economic liberalization could coexist with political repression. Its ruling elite—technocratic, nationalistic, and surveillance-driven—represents another version of post-ideological governance.

Across Eastern Europe, illiberal movements took power by appealing to cultural traditionalism while enriching their cronies through state capture.

Thus, what replaced communism was not democracy but a new global authoritarian network—a family of regimes united by corruption, mutual defense, and shared hostility toward liberal values. Their alliance is not doctrinal but transactional, bound by a common interest in preventing accountability.

The Illusion of Modernization

Many observers once believed economic modernization would inevitably lead to liberal democracy. Post-communist regimes disproved that assumption. They demonstrated that industrial and technological progress can thrive even under corrupt or authoritarian rule—so long as elites maintain control over resources and security apparatuses.

In Russia, technological resurgence in the defense and cyber sectors did not translate into openness or prosperity for the population. Instead, it reinforced the militarized state.

Likewise, in Central Asia, glittering new cities like Astana or Ashgabat coexist with deep political repression. These are showcases of “authoritarian modernity”—an aesthetic of progress masking moral decay.

The Psychology of the New Elite

What defines the mentality of those who replaced communist leadership is not ideology but ressentiment—an emotional mixture of humiliation, envy, and revenge. They resent the West for winning the Cold War, yet desire its wealth and luxury. They despise democracy’s messiness but crave its legitimacy. They view law not as a principle to protect society, but as a weapon to control it.

This dual consciousness—both cynical and inferiority-driven—creates a regime psychology that oscillates between imitation and defiance. The same figures who denounce Western decadence send their children to Western universities.

The same leaders who reject globalization stash their fortunes in offshore accounts. Their worldview is incoherent, but coherence is unnecessary when power itself provides purpose.

Resistance and Renewal

Despite the apparent dominance of this corrupt elite, resistance persists. In Ukraine, millions risked their lives in two revolutions to reject oligarchy and demand accountable government. In Belarus, protesters defied brutal repression after fraudulent elections.

In Russia itself, independent journalists, artists, and activists continue to challenge authoritarian structures, often at great personal cost.

The moral renewal of post-communist societies is possible—but it requires confronting not only political corruption but the deeper cultural nihilism that sustains it.

Societies must rediscover a moral vocabulary that transcends both the dogmas of communism and the cynicism of unrestrained capitalism. Without that, even democratic forms become hollow, mere theater performed for the cameras of a disillusioned age.

The West’s Reckoning

The West also bears responsibility for the world that emerged after communism. Its complacency, moral inconsistency, and worship of markets helped entrench the very forces it sought to defeat. By tolerating kleptocracy as long as it served economic interests, Western institutions undermined their own credibility.

Sanctions against post-Soviet oligarchs, though belated, reflect a growing recognition that corruption is a global security threat. Yet addressing its roots means rethinking the relationship between money and power in the West itself.

When the line between legal wealth and illegitimate influence blurs, democracy becomes vulnerable to the same disease that destroyed the moral core of the East.

The Unfinished Reckoning of History

Communism’s collapse was not the end of history, as some hoped—it was merely the end of one illusion. The systems that replaced it are not free of the past; they are haunted by it.

The authoritarian elite that governs much of the post-communist world are the heirs not of Marx or Lenin, but of the very cynicism that communism was supposed to eradicate: the belief that human beings are instruments, not ends.

History did not conclude in 1991; it mutated. What we witness today—in wars, disinformation, and moral decay—is the long, lingering aftershock of that unfinished collapse.

Until societies confront the spiritual bankruptcy that replaced communist dogma, the cycle of corruption and conflict will continue.

Toward a Moral Reawakening

To break this cycle, post-communist societies need not return to ideology, but to conscience. The genuine alternative to nihilism is not another “ism” but the restoration of moral agency—the belief that individuals and institutions can act with integrity, restraint, and empathy.

Examples exist. The Baltic States built functional democracies through transparency and civic responsibility.

In Eastern Europe, civil society movements have challenged authoritarian tendencies with persistence and creativity.

Even in Russia, underground networks nurture independent thinking and moral courage against overwhelming odds.

The global community, too, must learn humility. True solidarity with these struggles requires consistency—holding autocracies accountable not just when convenient, but always.

To confront corruption abroad, the West must confront complicity at home.

Conclusion

Ashes and Seeds

From the ashes of communism indeed emerged a corrupt, nihilistic, and warmongering elite. But from those same ashes, the potential for renewal also survives.

The story of post-communist societies is not only one of decay—it is also one of endurance, adaptation, and the slow rediscovery of moral meaning after ideological exhaustion.

The tragedy of the post-communist world lies not in the failure of any single system, but in the loss of faith—in truth, in justice, in the capacity of politics to serve humanity rather than enslave it. Yet history’s ashes often hide seeds.

The challenge for this century is whether those seeds will take root before the new elite—drunk on power, blinded by greed—consumes the ground entirely.