When the Dollar Lost Its Magic: Inside America’s Growing Capital Flight Crisis and What It Means for Global Power

Executive Summary

The United States faces an incipient phase of capital flight occasioned by policy unpredictability and structural fiscal imbalances.

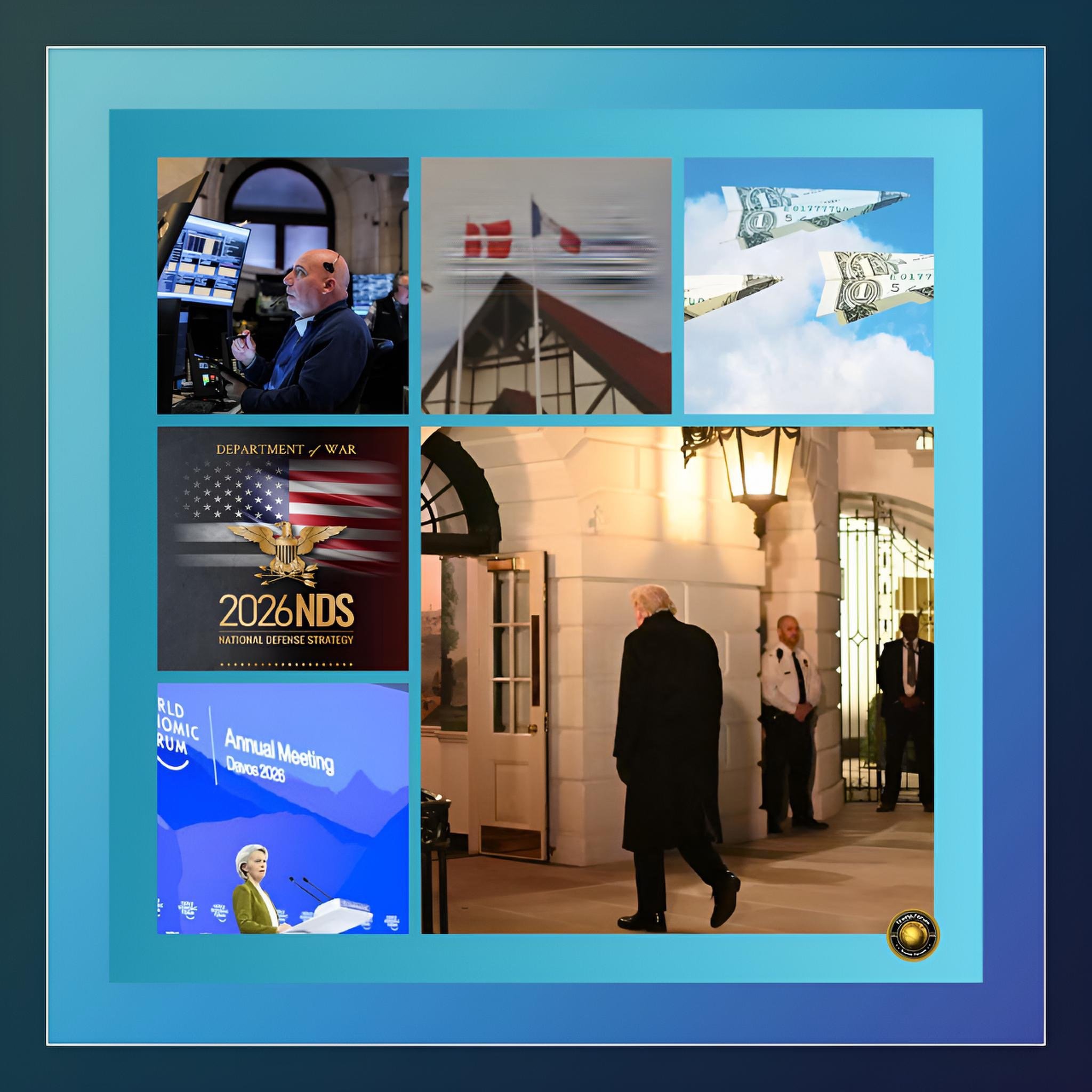

The proximate trigger emerged in January 2026, when the Trump administration's threats to acquire Greenland precipitated a synchronized decline in Treasury demand and a depreciation of the dollar, a phenomenon market analysts characterized as the reemergence of a "Sell America" trade.

This capital reallocation reflects a fundamental erosion of confidence in American institutional predictability and the long-term viability of dollar-denominated assets, as evidenced by measurable shifts among both foreign official holders and multinational investors.

The structural vulnerability of the United States to capital flight stems from its unprecedented net international investment position deficit of $27.61 trillion, coupled with declining foreign ownership of Treasury obligations and an accelerating decentralization of the global monetary architecture away from dollar hegemony.

If capital outflows persist at current trajectories and foreign demand for Treasury securities continues to decline, the consequences would include elevated borrowing costs, currency depreciation, domestic credit constraints, and, ultimately, a diminished capacity for global fiscal and military intervention.

Introduction

Capital flight refers to the rapid withdrawal of financial assets from a jurisdiction due to concerns about political stability, exchange rate risk, or anticipated macroeconomic deterioration.

While economies experiencing hyperinflation, authoritarian governance, or imminent sovereign default classically experience capital flight, the contemporary risk to the United States represents a qualitatively novel phenomenon: a developed economy possessing reserve currency status confronting potential investor reallocation not from weakness of fundamental demand for American assets, but rather from deteriorating confidence in political institutions and the predictability of policy frameworks.

The distinction is consequential. The United States maintains intense and liquid capital markets, technological dominance, demographic advantages relative to other developed economies, and geopolitical hegemony. Yet capital flight, by definition, cannot be remedied through marginal improvements in fundamentals if the drivers of flight are institutional and policy-based.

This analysis examines the mechanics of capital flight in the American context, historical precedents, the current trajectory of foreign disinvestment, and the multiplicative economic consequences should current trends not be arrested.

Current Status and Recent Developments

The proximate manifestation of capital flight emerged in mid-January 2026 when President Trump articulated his intention to acquire Greenland through economic or military means. The European Union, Denmark, and Greenlandic leadership uniformly rejected these overtures.

Trump subsequently threatened to impose escalating tariffs on eight NATO nations—Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Finland—commencing at 10% on February 1, 2026, and escalating to 25% on June 1, absent capitulation to American territorial demands.

The market response was immediate and diagnostic.

The Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index declined to a three-week low, marking the dollar's worst week since June 2025.

Critically, this decline occurred simultaneously with elevated Treasury yields, a configuration that contradicts historical correlations wherein capital flight triggers flight-to-safety inflows into dollar assets. Instead, the concurrent depreciation of the dollar and the rise in Treasury yields signal capital reallocation away from American assets toward foreign alternatives—a pattern economists have termed a "Sell America" trade.

Foreign investor behavior substantiated this interpretation. The Dutch pension fund ABP, Europe's largest, reduced its Treasury holdings from approximately $27.5 billion at year-end 2024 to $22 billion by September 2025, a contraction of more than 20%. This divestment was executed irrespective of Treasury price movements; bond valuations remained stable or appreciated during the period, indicating voluntary reallocation rather than valuation-driven losses.

Treasury International Capital data for October 2025 registered net foreign official outflows of $19.2 billion, while November 2025 recorded net private inflows of $167.2 billion. Official sector liquidation continued at $44.9 billion, revealing a dichotomous market in which private speculators accumulate while official holders divest.

The dimensional scale of foreign ownership compression cannot be overstated. Foreign holdings of United States Treasury securities have contracted from 49% of domestically held debt in 2011 to 32% by 2025.

More strikingly, China and Japan—historically the two largest foreign creditors of the federal government—have systematically reduced their direct Treasury allocations from a combined 50 % of all foreign-held Treasuries immediately following the global financial crisis to 25 % presently.

China's nominal holdings declined from $1.3 trillion in 2011 to $780 billion currently, though increased indirect holdings through custodial accounts partially obscure this deterioration.

Foreign Direct Investment and Equity Capital Flows

The contraction in capital flows extends beyond the Treasury market. Foreign direct investment—encompassing new acquisitions, mergers, and greenfield manufacturing facilities—experienced a precipitous deceleration commencing in Q1 2025.

New foreign equity investment plummeted 62.5 percent from the final quarter of 2024 to the initial quarter of 2025. Specifically, foreign portfolio equity purchases fell from $167.8 billion to $23.2 billion, a 86.2 percent contraction. Foreign direct investment fell more moderately but substantially, declining 33.7 percent from $88.5 billion to $58.7 billion over the same period.

These figures reflect the confluence of elevated business uncertainty stemming from Trump's "Liberation Day" tariff announcements in April 2025 and ongoing trade policy tensions.

The broader trajectory warrants emphasis. New foreign direct investment into the United States totaled $150.2 billion in 2025, representing a 14.2 percent decline from 2023 and standing 42 % below the 2015 peak of $450 billion.

This erosion has persisted despite the United States maintaining its global primacy as a destination for foreign capital; the country attracted approximately 20 % of worldwide foreign direct investment in 2024.

The deterioration is thus not absolute but relative—capital continues flowing into American assets, but at diminishing rates relative to historical precedents and to alternative jurisdictions.

These flows conceal compositional complexity. Private investors, predominantly multinational corporations and institutional asset managers, continue acquiring American assets, particularly given the elevated valuations and growth prospects of the technology sector.

Official investors—central banks and sovereign wealth funds—exhibit markedly divergent behavior, progressively reducing their dollar-denominated holdings as part of explicit de-dollarization strategies.

This bifurcation represents a qualitative shift from the immediate post-financial crisis epoch, when foreign official demand anchored Treasury markets and absorbed tremendous supply.

The Structural Vulnerability: The United States International Investment Position

The United States net international investment position represents the aggregate difference between American residents' foreign financial assets and the market value of liabilities owed to foreign entities.

This metric synthesizes all categories of cross-border investment—portfolio securities, foreign direct investment, banking claims, and derivatives.

The figure for the third quarter of 2025 stood at minus $27.61 trillion, an amplification from minus $26.16 trillion in the preceding quarter. American residents held $41.27 trillion in foreign assets, whilst foreign residents held $68.89 trillion in United States assets, a structural imbalance unprecedented in American history.

This inversion is not transient but reflects decades of current account deficits, whereby the United States continuously imports more goods and services than it exports, necessitating financing through capital inflows. The deficit persists despite the dollar's status as a reserve currency, which, in theory, should incentivize foreign accumulation of dollar assets.

That foreign investors continue to acquire American assets despite a negative net international investment position indicates the residual attractiveness of United States assets relative to available alternatives—but margins are compressing.

The compositional dynamics of this deficit warrant particular scrutiny. The deterioration from Q2 to Q3 2025 of $1.46 trillion was partially due to financial transactions of minus $386.1 billion, indicating net disinvestment, and partially to valuation effects of minus $1.07 trillion.

These valuation shifts, paradoxically, reflected United States stock price appreciation exceeding foreign stock market gains, thereby augmenting the market value of foreign liabilities in American markets.

In other contexts, such equity appreciation would be salutary; in this configuration, it signals a malign dynamic wherein foreign assets appreciate whilst foreign ownership of American assets simultaneously expands in percentage terms.

Historical Precedents: Capital Flight and Economic Catastrophe

The international economic record furnishes instructive precedents concerning the consequences of capital flight.

The 1997 Asian financial crisis originated not from fundamental deterioration in Thai economic productivity but from unsustainable currency pegs, foreign exchange reserve depletion, and inadequate foreign debt management. When Thailand exhausted its capacity to defend the baht, a rapid reversal ensued.

Bank lending to Asian borrowers inverted from net inflows of $40 billion in 1996 to net outflows exceeding $30 billion, representing approximately seven percent of regional GDP. This capital withdrawal, characterized by simultaneity across multiple jurisdictions, manifested contagion dynamics wherein investors reduced exposures to all Asian emerging markets, not merely crisis-origin Thailand.

The consequence was devastating. Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand experienced currency collapses, equity market depreciations exceeding 50 %, widespread corporate insolvency, banking system failures, and unemployment surges. GDP per capita contracted sharply across the region.

Recovery, whilst relatively rapid by historical standards, required International Monetary Fund intervention, structural adjustment, and multi-year adjustment periods.

The 1997 crisis, despite originating in a region accounting for less than 2% of global GDP, triggered contagion that spread to Russia, Brazil, and hedge funds in developed markets, illustrating the mechanisms by which peripheral capital flight can cascade.

Argentina's experience from 1998 to 2002 illuminates the domestic consequences of capital flight in a mature economy. Beginning in 1998, Argentina entered a recession, transitioning into a depression by 2001 as economic activity contracted sharply.

The capital flight was immense: $150 billion left the country during the 1990s, exceeding the nation's total foreign debt. The government, constrained by its commitment to a currency board pegging the peso to the dollar, could neither expand monetary aggregates to offset capital outflows nor devalue to restore competitiveness.

Instead, the nation entered a liquidity trap in which depositors rushed to withdraw funds, foreign exchange reserves depleted, and the government imposed a corralito—a freeze on bank withdrawals that restricted citizens to minimal daily withdrawals.

The economic contraction was apocalyptic by developed-world standards.

GDP per capita fell approximately 20 percent from peak to trough. Unemployment surged from 13% in 1998 to 25% by 2002. The social fabric fractured: over 50 % of the population fell below the official poverty line, with 25 % classified as indigent.

The government defaulted on $85 billion of sovereign debt, the largest default in history at that juncture. The president resigned, and successive interim administrations followed, unable to command legislative confidence. The peso collapsed from one-to-one parity with the dollar to three pesos per dollar within weeks.

Argentina's recovery, whilst dramatic post-2003, required a decade for living standards to recover to pre-crisis levels.

The recovery itself was contingent upon a global commodity boom, which inflated prices for Argentine agricultural exports, providing the foreign exchange necessary to service debt. Absent such exogenous fortune, the recovery trajectory would have extended substantially longer.

The pertinent lesson transcends national specificity: once initiated, capital flight becomes self-reinforcing. Investors who observe capital departing anticipate currency depreciation and accelerate their own exits, creating a vicious cycle wherein assets depreciate far beyond fundamentals-justified levels.

Mechanisms of Capital Flight and Interest Rate Dynamics

The transmission mechanism through which capital flight affects macroeconomic outcomes operates principally through the Treasury market. The United States federal government issues approximately $29 trillion in Treasury obligations, making the Treasury market the largest, most liquid sovereign debt market globally.

Foreign investors have historically provided significant demand for these securities, with foreign holdings reaching nearly 50 percent of domestically-held debt during the early 2010s.

The economics underlying this demand are straightforward. Treasuries provide a liquid, nominally risk-free investment denominated in the global reserve currency, offering genuine value to foreign central banks that must maintain foreign exchange reserves and to private investors seeking geopolitical stability. The demand for Treasuries, however, exhibits price elasticity variations across investor categories and temporal periods.

Scholarship using Treasury International Capital data suggests that a one-standard-deviation decrease in foreign holdings—approximately $141 billion—would raise yields on the ten-year Treasury by approximately 57 basis points, or 0.57 percentage points.

The mechanism deserves explication. As foreign investors reduce purchases or liquidate existing holdings, the supply of Treasuries available for domestic absorption increases. Domestic investors—principally banks, insurance companies, and pension funds—have distinct yield elasticities compared to official foreign investors.

Official foreign investors, motivated substantially by transaction settlement requirements and strategic reserve accumulation rather than yield maximization, demonstrate considerable price inelasticity. Domestic private investors, by contrast, exhibit pronounced yield-sensitivity; they require compensation to absorb additional supply.

This compositional shift assumes profound significance given the structural transition in the Treasury market since the global financial crisis. Before 2008, foreign official institutions—central banks and governments—rapidly accumulated Treasuries, driven by persistent mercantilist trade surpluses and foreign-exchange intervention in Asian and Middle Eastern economies.

This demand was relatively insensitive to price movements, anchoring yields at lower levels than pure market-clearing mechanics would generate. Since 2008, however, the Federal Reserve has conducted sustained Treasury purchases through quantitative easing programs, establishing itself as the marginal buyer and, critically, demonstrating price-insensitive demand contingent upon financial stress metrics.

The transition from foreign official demand to Federal Reserve demand to private domestic demand fundamentally alters the yield dynamics of the Treasury market. When marginal demand emanates from price-insensitive foreign officials, yields remain compressed. When the Federal Reserve becomes the marginal buyer during stress episodes, yields decline despite potential supply expansion.

Conversely, when marginal demand emanates exclusively from price-sensitive domestic investors, the same incremental supply requires substantially elevated yields to clear markets. The ongoing capital flight, combined with the Federal Reserve's constrained capacity to purchase Treasuries without inflating the monetary base, creates a structural configuration in which yields must rise substantially to absorb the remaining supply.

The consequence for fiscal sustainability becomes apparent. The United States federal government confronts a budget deficit approaching 6.0% of GDP in fiscal year 2025, despite positive economic growth.

The federal debt exceeds $38 trillion, representing more than 100 percent of annual GDP. Most alarmingly, net interest on the national debt has nearly tripled over the past five years and now accounts for approximately 14% of federal spending.

This interest burden is mathematically destined to rise further as existing low-yield debt matures and must be refinanced at elevated rates. Should capital flight persist, and foreign demand for Treasuries continue to attenuate, refinancing pressures would intensify, potentially triggering fiscal crisis dynamics.

De-Dollarization and the Erosion of Reserve Currency Status

Capital flight from the United States manifests as a component of broader de-dollarization trends, in which central banks and international investors reduce their allocations to dollar-denominated assets in favor of alternative reserves—gold, euros, yuan, and emerging alternative arrangements.

These trends predate the Trump administration but have accelerated notably since 2024.

The incentives driving de-dollarization are multifaceted.

First, the dollar's reserve currency status confers upon the United States an "exorbitant privilege," in economist Valéry Giscard d'Estaing's formulation, allowing the federal government to borrow at lower costs than would otherwise be available and to finance persistent fiscal deficits through capital inflows rather than through adjustment.

Second, reserve currency status empowers American authorities to weaponize the dollar through sanctions and asset freezes, exemplified by the post-2022 freeze of Russian central bank reserves and the sequential imposition of sanctions against Iran, Venezuela, and other geopolitical adversaries.

This weaponization, whilst advancing American interests, simultaneously incentivizes alternative jurisdictions to construct monetary systems less dependent upon dollar access.

Third, the concentration of the Treasury market liquidity in a single jurisdiction creates tail risks. Should capital flight accelerate sufficiently, the liquidity and safety attributes of Treasuries could themselves degrade, creating a cascade in which investors rationally reduce holdings, further degrading those attributes, inducing additional reductions. This adverse feedback cycle represents the classic dynamic of currency crises.

The empirical manifestations of de-dollarization appear across multiple dimensions. The dollar's share of global foreign exchange reserves has contracted from approximately 65% in the early 2000s to roughly 56% by late 2025, a decline of approximately 9 percentage points, representing a significant erosion of dominance. Central banks have accelerated purchases of gold, with global acquisitions exceeding recent historical averages.

The yuan has expanded its role in international trade settlements, though from a modest base. Emerging economies increasingly engage in bilateral trade arrangements denominated in non-dollar currencies, reducing their dependence upon dollar intermediation.

The Atlantic Council and Federal Reserve analyses have characterized these trends as genuine existential challenges to the dollar's reserve status, though not yet determinative.

The political fragmentation and institutional polarization within the United States, coupled with what market participants perceive as policy unpredictability and brinksmanship over the debt ceiling, have accelerated the psychological transitions underlying de-dollarization. Investor perception, not purely objective fundamentals, determines a reserve currency's status; once confidence erodes sufficiently, the decline becomes self-reinforcing.

The Policy Uncertainty and Institutional Predictability Crisis

The contemporary episode of capital flight differs from historical crises in emerging markets in its origins. Thailand in 1997 exhibited external imbalances, currency pegs, and financial fragility—classical antecedents to a currency crisis. Argentina in 2001 possessed unsustainable fiscal positions and current account deficits—recognizable precursors.

The United States in 2026 exhibits no equivalent fundamental deterioration. American labor productivity remains among the highest globally. Demographic trends, whilst suboptimal relative to prior decades, exceed those of Europe and Japan. Technological dominance, particularly in artificial intelligence infrastructure, remains unchallenged. Energy security has improved dramatically through domestic natural gas production.

What has deteriorated is institutional and political predictability. The Trump administration has articulated policy positions inconsistent with postwar international economic institutions.

The 2025 "Liberation Day" tariff announcements, whilst subsequently revised, demonstrated the administration's willingness to impose trade barriers on allied nations without extended consultation. The January 2026 Greenland acquisition rhetoric, initially expressed with ambiguity regarding military versus economic means, signaled unpredictability concerning territorial and alliance relationships.

The administration's threats to eliminate the Federal Reserve's independence, whilst not formally operationalized, created uncertainty concerning monetary policy transmission mechanisms.

These developments, individually manageable, collectively created psychological conditions that led sophisticated foreign investors to reassess their holdings.

The process exhibits self-reinforcing dynamics. As the dollar depreciates due to incipient capital flight, American exports become more competitive and imports more expensive, mechanically improving the current account balance. Conversely, as the dollar weakens and Treasury yields rise, the attractiveness of dollar assets diminishes further, accelerating capital flight.

The virtuous cycle from stable institutional expectations could invert into a vicious cycle absent policy course correction.

Consequences of Persistent Capital Flight

Should capital flight persist, and foreign demand for American assets continue to attenuate, multiple economic consequences would manifest across temporal horizons.

Immediate Effects encompass Treasury market volatility and elevated yields. A $141 billion reduction in foreign holdings would raise ten-year yields by approximately 57 basis points. Given that foreign holdings exceed $8 trillion, even modest reductions would have a substantial impact on yields.

Elevated Treasury yields would cascade through corporate bond markets, as corporations finance investment at the risk-free rate plus spreads. Higher borrowing costs would reduce capital expenditure, slowing investment and growth. The stock market, which has benefited from exceptional liquidity and low discount rates, would face valuation compression as the cost of capital increases.

Medium-Term Effects involve monetary-fiscal interaction and crowding-out dynamics. The Federal Reserve, confronting elevated Treasury yields stemming from foreign disinvestment, would face pressure to accommodate by purchasing additional Treasury securities to stabilize financial conditions.

Such accommodation would expand the monetary base without corresponding economic growth, creating inflationary pressures. Simultaneously, elevated Treasury yields crowd out private investment; corporations rationally reduce capital expenditure when government borrowing costs rise. The net effect would be slower productivity growth and elevated inflation—a stagflationary configuration.

Long-Term Consequences encompass loss of reserve currency status and geopolitical implications. Should the dollar's international role contract materially, the United States would lose the exceptional borrowing privileges it currently enjoys.

Federal borrowing costs would converge toward rates required to attract purely economically-motivated investors rather than official holders. The fiscal adjustment would necessitate either substantial tax increases or entitlement spending reductions—politically intractable decisions. The reduced financial capacity would constrain military expenditure, curtailing American capacity for sustained overseas military engagement and alliance maintenance.

Empirical models suggest that loss of reserve currency status would not occur rapidly but rather over decades.

The euro, despite the European Union's institutional deficiencies, has not remotely approached the dollar's dominance after more than two decades of existence. Nonetheless, the trajectory matters enormously for American strategic capacity and living standards.

Conclusion

The capital flight presently manifesting in American markets represents not a discrete crisis but rather the incipient phase of a potential loss of confidence in American institutional stability and fiscal sustainability.

The January 2026 Greenland episode served as a psychological inflection point, triggering reallocation that had been building through 2025 but had not yet registered in asset prices.

The structural vulnerabilities underlying this Capital flight are not transient.

The United States international investment position deficit of $27.61 trillion cannot be remedied through growth alone; it requires either current account improvement, which would necessitate either a depreciation of the dollar or a reduction in consumption relative to investment, or continued foreign willingness to accumulate dollar assets at current rates.

The fiscal trajectory—deficits approaching 6% of GDP, debt exceeding 100% of GDP, and interest expense consuming 14% of federal spending—is mathematically unsustainable. The institutional deterioration in perceived predictability and independence of the Federal Reserve further compounds investor hesitation.

Historical precedents—the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 2001 Argentine catastrophe—demonstrate that capital flight, once initiated, exhibits extraordinary persistence and cascading consequences.

The transmission mechanism through which capital flight constrains growth operates via interest rates, currency depreciation, and reduced fiscal capacity. Prevention requires restoring institutional confidence and demonstrating fiscal sustainability through policy reform.

The immediate issue for policymakers, investors, and strategic planners is whether capital flight remains reversible through policy course correction or whether the erosion of confidence has advanced sufficiently to become path-dependent.

The magnitude and duration of the January 2026 capital flight episode will provide signals concerning whether the process remains tractable or whether structural transitions toward a multipolar monetary system have become inevitable.

The consequences of mismanagement extend far beyond financial markets, encompassing the long-term geopolitical position and living standards of the United States itself.