Summary

A Simple Explanation: Why Foreign Money Matters to America

Imagine America is like a big business. For decades, investors from around the world have sought to buy stakes in this business. They buy government bonds (essentially loans to America), buy stocks of American companies, build factories here, and keep money in American banks. This foreign investment is like oxygen for the American economy—it keeps things running smoothly.

But what happens if foreign investors suddenly lose confidence and start withdrawing their money?

That is capital flight, and it is happening right now in early 2026.

Understanding this process is essential because the consequences touch everything from jobs to gas prices to the military's ability to protect American interests overseas.

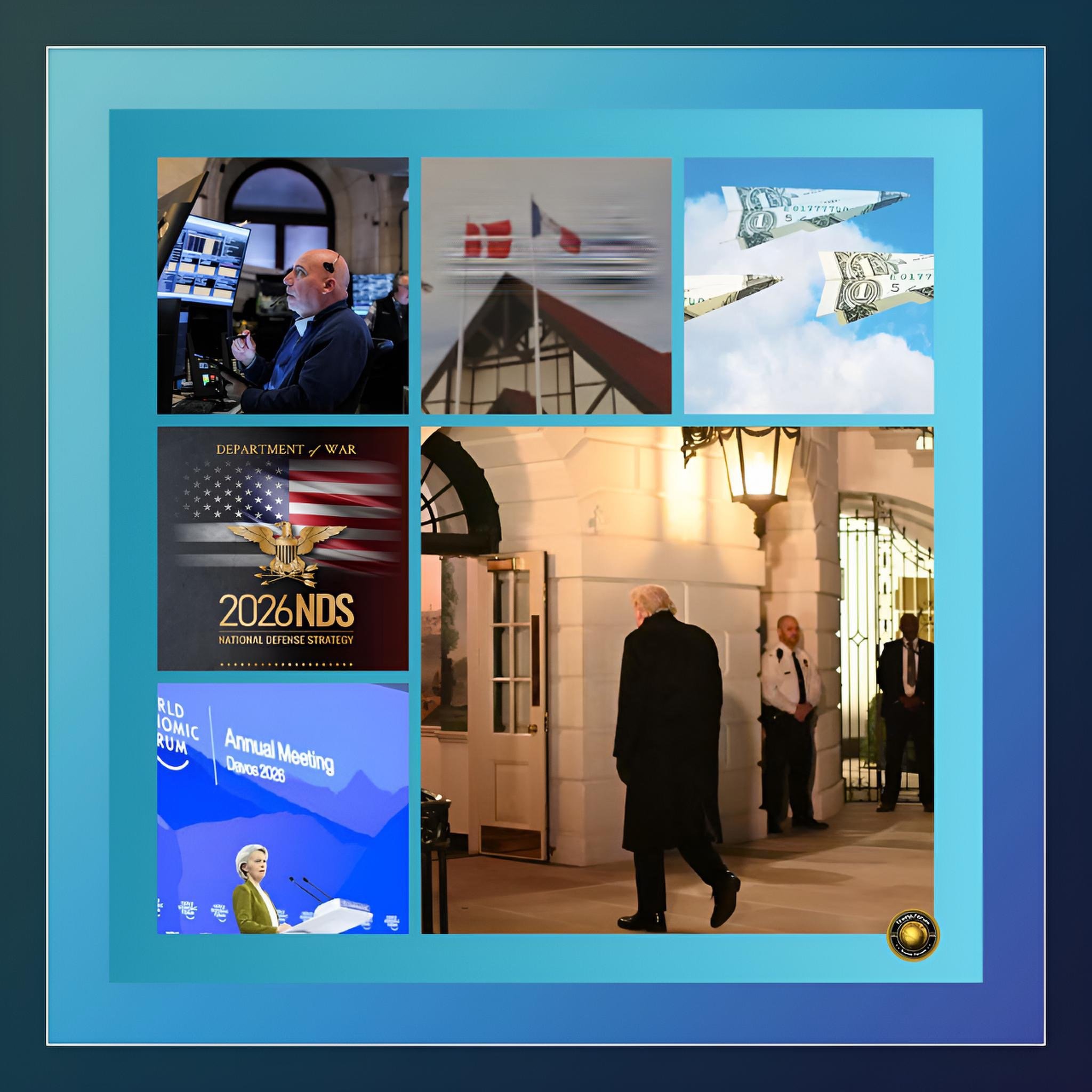

The Current Situation: January 2026 and the Greenland Crisis

In January 2026, President Trump announced his intention to acquire Greenland from Denmark. He said the United States might do this "the hard way" if Denmark refused. He threatened Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Finland with a 10 % tax on their products, effective February 1, 2026. If they still refused to agree to America having Greenland by June 1, those taxes would jump to 25 %.

Foreign investors watched this and became nervous. They started thinking: "Is America predictable anymore?

Can we trust this government?"

Within days, foreign investors and banks began selling American investments.

The dollar weakened against other currencies. American government bond prices fell. This pattern was so clear that financial experts nicknamed it the "Sell America" trade.

Here is what happened in absolute numbers: Europe's largest pension fund (which manages retirement money for Dutch workers) cut its holdings of American bonds from about $27.5 billion at the end of 2024 to $22 billion by September 2025.

That is cutting their investment in America by more than one-fifth.

Pension funds do not make these decisions lightly—when they reduce American investments, it signals genuine concern about America's future.

Why Foreign Money Matters: The Mechanics

The United States government borrows enormous amounts of money. Right now, the government has borrowed about $38 trillion—more than any American household earns in ten years.

How does it borrow this much? By selling Treasury bonds (basically IOUs) to investors worldwide.

Here is where the problem begins: The United States no longer saves enough internally to fund its own spending. The government needs foreign investors to buy its bonds. Without them, the government would not be able to pay for the military, roads, schools, and social programs.

In 2011, foreign investors owned nearly 50% of all American government bonds held by the public. Today, foreign investors own only about 30%.

This means America is increasingly dependent on domestic (American) investors to fund government borrowing. But domestic investors are more picky than foreign investors were.

Domestic investors say, "If I am going to lend America money, I want higher interest rates because I am uncertain about the future."

When interest rates rise, government borrowing costs rise too. Mortgages for homebuyers become more expensive. Loans for small businesses cost more. Car loans increase. Credit card interest rises. The Federal Reserve, America's central bank, has less power to lower interest rates when capital is fleeing.

The Greenland Crisis and the Dollar Decline

The Greenland situation triggered what investors call a "currency crisis signal."

Something unusual happened: the dollar weakened while government bond yields rose.

Typically, these move in opposite directions. When investors become nervous about America in general (not just specific bonds), they usually buy Treasury bonds as a "haven." This demand pushes bond prices up and yields down. But in January 2026, both the dollar and bond yields moved in the wrong direction—the dollar fell while yields rose.

This signal meant: "Foreign investors are not just adjusting their portfolios. They are getting out of America entirely."

One analyst explained it this way: "They are not moving from American stocks to American bonds. They are moving from American dollars to euros, yen, and other currencies."

The dollar index, which measures the dollar's strength against a basket of other major currencies, fell to a three-week low.

This was the worst week for the dollar since June 2025. Options traders (who bet on currency movements) started paying premiums to protect themselves against further dollar losses—something they rarely do unless they fear significant disruption.

Capital Flight in History: What Happens

To understand America's risk today, it helps to look at what happened to other countries when capital flight occurred. History shows a clear pattern.

Thailand 1997: The Asian Financial Crisis

In July 1997, Thailand ran out of foreign currency reserves trying to keep its currency stable.

Investors panicked. Instead of investing new money in Thailand, they raced to withdraw money.

Bank lending to Thailand and nearby countries flipped from $40 billion flowing in (1996) to $30 billion flowing out (1997)—a swing of $70 billion in just one year.

The damage spread like a disease. Because investors worried about the entire region, they also pulled money from South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

The crisis spread beyond Asia to Russia and Brazil. This "contagion" happened because investors treated entire regions as risky, not just individual countries.

The human cost was severe. In South Korea, millions lost their jobs. In Indonesia, poverty spiked. Currency values collapsed—imagine your savings are suddenly worth half as much.

The crisis took years to recover from, and required help from the International Monetary Fund (basically, emergency loans from the world's financial institutions).

Argentina 2001: A Developed Nation in Crisis

Argentina in the late 1990s seemed stable. It had a currency board—meaning its peso was worth exactly one American dollar, guaranteed by law. But the government kept spending more money than it collected in taxes. Companies struggled to compete globally. Investment slowed.

Between 1990 and 2001, $150 billion fled Argentina—more than the country's entire foreign debt. Investors wanted their money out.

The government, desperate, imposed a "corralito"—a rule that limited people to withdrawing only small amounts of cash from their bank accounts per day. Imagine needing to buy groceries or pay rent, only to be told: "You can only withdraw $100 today."

The impact was apocalyptic. Between 1998 and 2002, the economy shrank by 28%.

Unemployment rose from 13% to 25%.

More than half the population fell below the poverty line. The government defaulted on $85 billion of debt—the largest default in history at that time. The currency, supposedly worth one dollar forever, collapsed to three pesos per dollar within weeks.

Argentina did recover, but it took years.

Even today, Argentines describe 2001-2002 as a national trauma. The lessons: Once capital flight starts, it becomes self-reinforcing.

Each investor who sees money leaving thinks, "I should leave too." Predicting where it stops is nearly impossible.

The Structure Problem: Why America Is Vulnerable

America has a serious problem hiding in the statistics. The country owes more to foreigners than foreigners owe to America. This is called the net international investment position, and America's is negative $27.61 trillion as of late 2025.

What does this mean?

Americans own about $41 trillion in foreign assets (factories, stocks, bonds, and businesses abroad).

But foreigners own about $69 trillion in American assets (factories, stocks, bonds, and real estate here).

The difference is $28 trillion of debt-like exposure. This is the most significant deficit of this type in American history.

This happened because America has run trade deficits for decades—the country imports more goods from China, Germany, Japan, and others than it exports to them.

To pay for these imports, foreigners accumulated American assets. The process continued because foreigners wanted these assets.

But now, that willingness is weakening.

The Three Ways Capital Flight Hurts the Economy

If foreigners continue pulling money out of America, three concrete problems emerge:

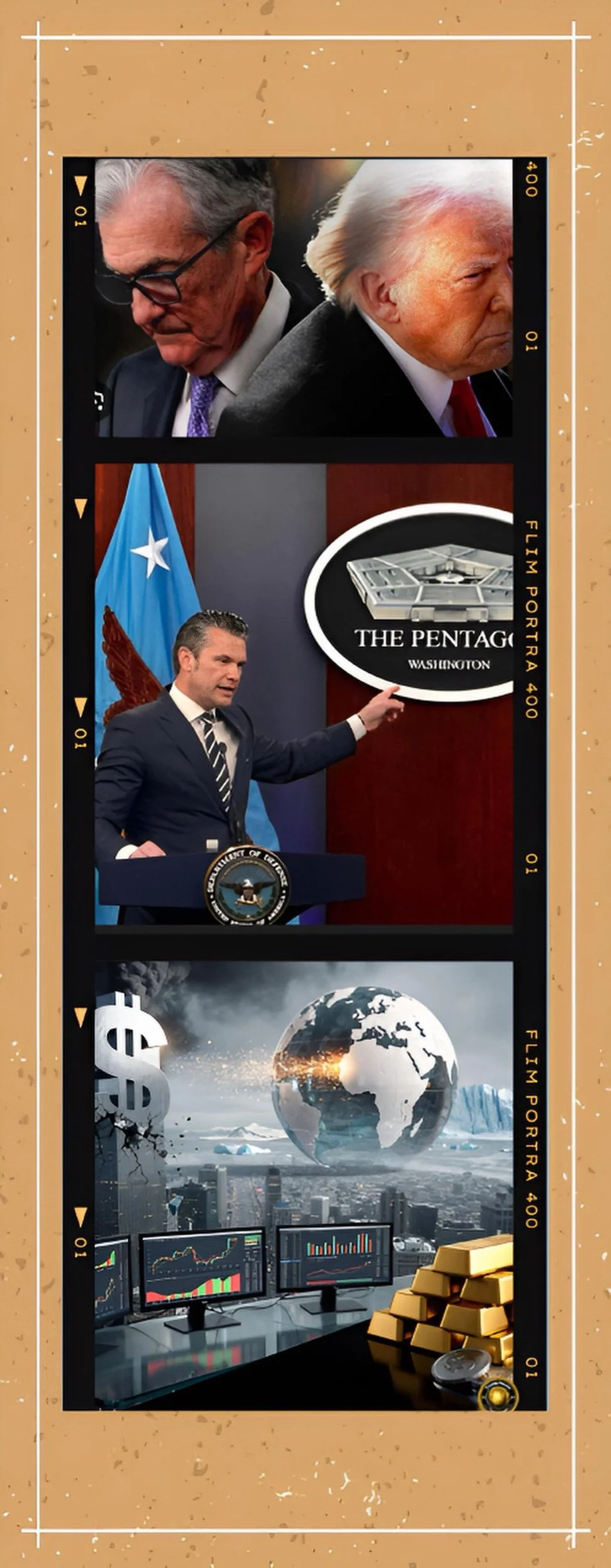

First: Interest Rates Rise

When foreigners stopped buying as many government bonds in October 2025, the government needed to attract domestic buyers. To do that, it had to offer higher interest rates. Research shows that losing $141 billion in foreign demand for Treasury bonds pushes ten-year interest rates up by about 57 basis points—more than half a percent.

When government borrowing rates rise, everything rises. Banks borrow from the Federal Reserve at the government bond rate plus a small spread. When that government rate goes up, the bank's cost increases. To maintain profits, banks charge customers more. A mortgage that cost 6 % becomes 6.5 % or 7 %.

A car loan becomes more expensive. A small business struggling to expand abandons its plans because the interest on a $500,000 loan has become unaffordable.

Multiply this across millions of decisions, and growth slows. Companies invest less. Workers are not hired to build new factories. Wages stagnate.

Second: The Dollar Weakens

Capital flight causes the dollar to depreciate. Foreigners holding dollars sell them—the supply of dollars increases. Like any supply increase, the price falls.

A weaker dollar has two consequences.

Positively, it makes American products cheaper for foreigners to buy, boosting exports and manufacturing jobs.

Negatively, it makes imported goods more expensive for Americans. If you purchase clothing made in Vietnam, or electronics made in China, or cars with parts from Mexico, prices rise. This increases inflation.

A weaker dollar also means traveling abroad becomes expensive. A European vacation costs more dollars because euros cost more.

Third: Fiscal Constraints and Hard Choices

The federal government currently runs deficits of nearly 6 % of GDP despite the economy growing. It borrowed $38 trillion.

Interest payments on this debt now account for 14% of all federal spending—roughly $1 trillion per year. This is the fastest-growing category of government spending.

If capital flight continues and interest rates rise, the government faces a choice.

It can:

(A) Raise taxes—unpopular politically

(B) Cut spending on military, Social Security, Medicare, or other programs—also unpopular

(C) Keep borrowing at higher costs—making the debt problem worse

(D) Reduce the dollar's value through printing money, causing inflation

None of these options is attractive. Each involves sacrifices. But continuing the current policy is mathematically impossible. Eventually, choices become forced.

The Geopolitical Angle: Reserve Currency Status

The dollar's dominance is not accidental. After World War II, America was the world's largest economy with the strongest military.

Countries trusted America and agreed to use the dollar for international trade. This "reserve currency status" gives America exceptional power.

With a reserve currency status, America can borrow cheaply and run deficits for decades. No other country gets this privilege. China, Japan, and Germany cannot borrow as cheaply because investors do not trust their currencies as global currencies.

But reserve currency status depends on trust. If enough countries decide the dollar is not stable, they will stop using it. They will trade in euros, yuan, gold, or other currencies. This would be catastrophic for America because:

First, borrowing costs would jump. America would pay what other countries pay, much higher.

Second, the military would be constrained. Military power is expensive. Without cheap borrowing, the US cannot afford bases worldwide and a rapid response to distant conflicts.

Third, geopolitical influence would evaporate. When America cannot easily fund allies or respond to crises, other powers (such as China and Russia) fill the vacuum.

The evidence of decline is already visible.

In 2000, the dollar represented about 70% of global foreign exchange reserves.

By 2025, it is about 56%. Central banks are buying gold instead of dollars. The yuan is gaining a role in international trade. The dollar is gradually being displaced.

What Would a Real Crisis Look Like?

If capital flight accelerated dramatically, America could face a scenario resembling Argentina 2001 in a few particulars, though with differences due to America's size and reserve currency status.

Scenario: A Spreading Crisis

Suppose foreign governments decide the United States is becoming politically unstable. Central banks, pension funds, and investors simultaneously sell American assets—the dollar plummets. Treasury yields spike—stock markets crash. Credit becomes expensive. Companies delay hiring. Unemployment rises.

At this point, consumers become nervous. They reduce spending. Businesses, seeing falling demand, cut jobs. Unemployment rises further. Federal revenues fall because fewer people are working. But spending on social programs rises because more people are unemployed. Deficits explode. The government borrows more at higher costs. Interest rates spike again. The cycle becomes self-reinforcing.

In extreme scenarios, the government might face a choice: default on debt or print money. Both options are catastrophic. Default destroys the dollar's credibility. Printing money causes inflation, which destroys the dollar's value.

This scenario is unlikely—America has tremendous advantages, including technological dominance, military power, and the world's largest economy. But it is possible if institutional confidence erodes sufficiently.

How Likely Is This?

Several factors suggest the risk is real but not imminent.

Positive Factors:

America has deep, liquid financial markets. Capital flight takes time. It does not happen instantly.

America still dominates technology, particularly artificial intelligence and semiconductors. This attracts investment.

American demographics are better than those in Europe or Japan, supporting long-term growth.

The dollar still dominates global finance. Alternatives are not ready to replace it.

American military power, while expensive, remains unchallenged.

Risk Factors:

The federal budget deficit is unsustainable at current levels.

Institutional predictability has declined—tariffs are imposed suddenly, debt-ceiling crises loom, and Federal Reserve independence is questioned.

Foreign holders of Treasury bonds are already reducing holdings.

Central banks are explicitly diversifying away from dollars.

The Greenland episode signaled instability to international investors.

Fiscal pressure will force difficult choices within a decade.

The Historical Record Suggests a Gradual Decline, Not a Sudden Collapse

Reserve currencies have been displaced before, but slowly. The British pound dominated global finance from the 1800s through the 1940s. The shift to the dollar took decades. The transition to a post-dollar system, if it occurs, would similarly unfold over years or decades, not months.

This gradual trajectory actually makes the problem harder in some respects. Because decline is slow, policymakers can convince themselves that action is not urgent. But compound effects accumulate. At some point, thresholds are crossed, and cascades become unstoppable.

What Would Fix This?

To restore confidence and prevent capital flight from accelerating, America would need to address the underlying causes:

First: Restore Fiscal Sustainability

The government must demonstrate that deficits will decline and debt will stabilize. This requires either raising revenue (through taxes) or reducing spending (on programs). Both are politically difficult. But without visible progress on deficits, investors will remain skeptical.

Second: Demonstrate Institutional Stability

Policy should become more predictable. Tariffs should be announced with notice, not suddenly. The Federal Reserve should be treated as independent. Debt ceiling negotiations should be treated as formalities, not as opportunities for brinkmanship. International partners should be consulted before major policy shifts.

Third: Support the Dollar's International Role

This might seem contradictory—if capital is fleeing, should America encourage the use of dollars? Yes. The dollar's dominance benefits America. Policies that undermine other economies' faith in dollar-denominated assets accelerate de-dollarization. The solution is not to weaponize the dollar through sanctions—which encourages alternatives—but to make the dollar attractive through stability.

Fourth: Reform Long-Term Growth Engines

America needs policies supporting productivity, investment, and innovation. With faster growth, deficits naturally decline. With more rapid growth, fiscal sustainability becomes achievable. But this requires sustained focus, not shifting priorities every administration.

Conclusion

Why This Matters to You

Capital flight might sound like an abstract financial concept, but it directly affects your life. If interest rates rise due to capital flight, your mortgage becomes more expensive, or your home purchase becomes unaffordable.

If inflation rises because the dollar weakens, your grocery bill increases. If the government faces fiscal constraints, it cuts programs you depend on or raises taxes on you. If America loses its reserve currency status, its military capability and geopolitical influence decline, potentially creating security risks.

The January 2026 Greenland crisis was a warning signal. It showed that foreigners will react to perceived instability by moving money. If such signals are ignored and trends continue, America faces not an acute crisis but a slow-motion erosion of the advantages that have made it the world's leading economic and military power.

Prevention is still possible. It requires fiscal discipline, institutional stability, and recognition that America's global position is not automatically permanent—it must be maintained through competent governance.

The window for course correction remains open, but it is gradually closing. The decisions made in 2026 and beyond will determine whether American economic dominance extends another century or whether the twenty-first century becomes defined by American decline.