The Empire Strikes Back: How Tehran’s Massacre Exposed the Regime’s Terminal Desperation

Summary

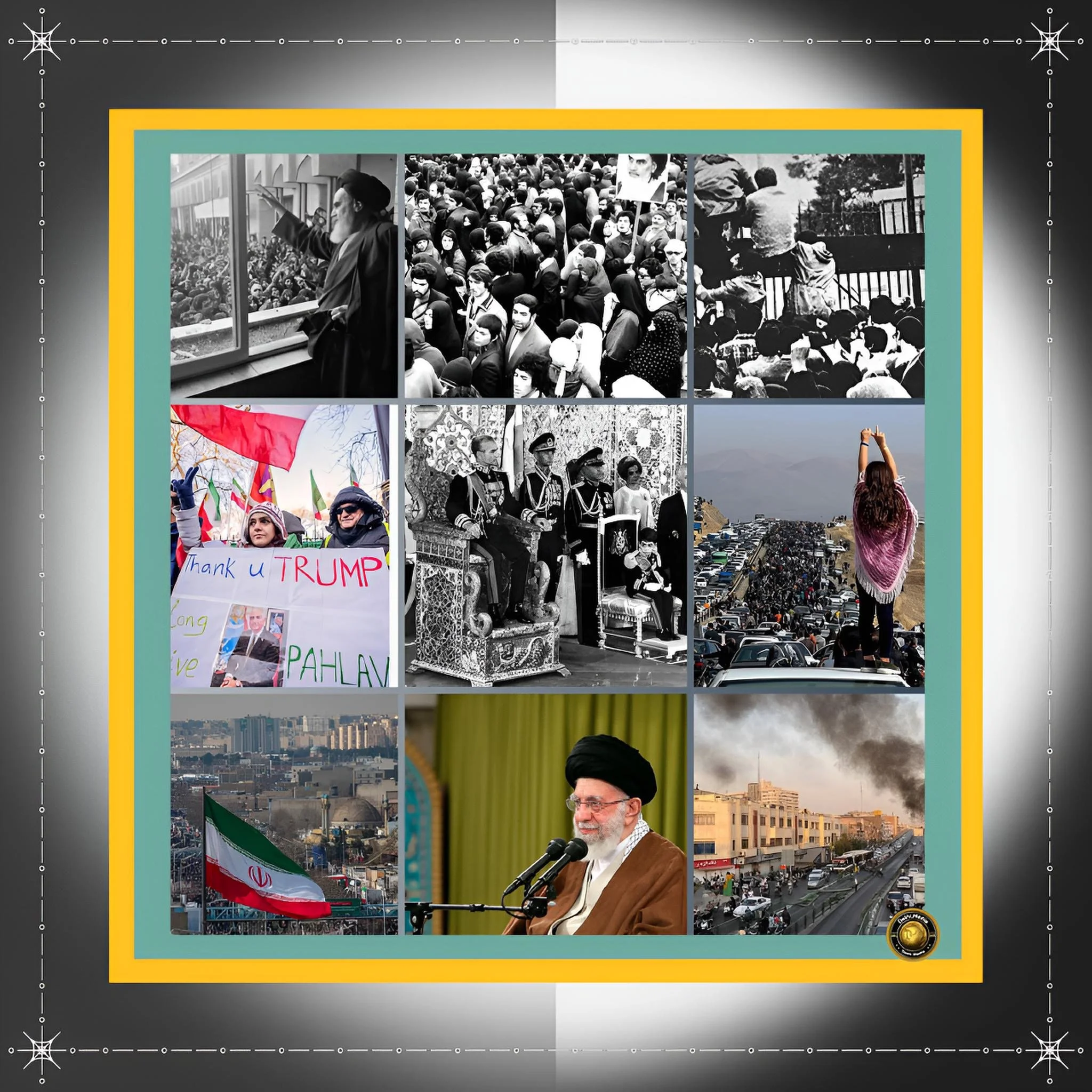

In the opening weeks of 2026, the Islamic Republic of Iran embarked upon a course of action that may ultimately prove to be the beginning of its end. Not because the massacres of January will necessarily topple the regime—such predictions are notoriously unreliable—but because the regime's leadership has demonstrated, in blood and terror, that it possesses no other solution to the fundamental crises arrayed against it.

The story begins, as so many crises do, with money. Iran's currency, the rial, has been in slow-motion collapse for decades, a steady drain of purchasing power reflecting international sanctions, chronic mismanagement, and the extraordinary costs of maintaining regional proxy networks. But in 2025, the deterioration accelerated catastrophically.

The rial commenced the year at 817,000 per US dollar and finished near 1.5 million—an eighty percent depreciation in twelve months. This was not a financial technicality. For ordinary Iranians, it meant that a loaf of bread that cost a certain amount on January 1 was unaffordable by July. A middle-class salary that had provided modest comfort became inadequate. Savings accumulated over a lifetime evaporated.

The implicit social contract—that people would accept restricted political freedoms in exchange for basic material security—was shattered not by regime policy but by economic reality.

When merchants in Tehran's Grand Bazaar shuttered their shops on December 28, they were not making a political statement. They were responding to the immediate fact that they could not afford to purchase inventory at parallel-market currency rates while selling at prices consumers could pay.

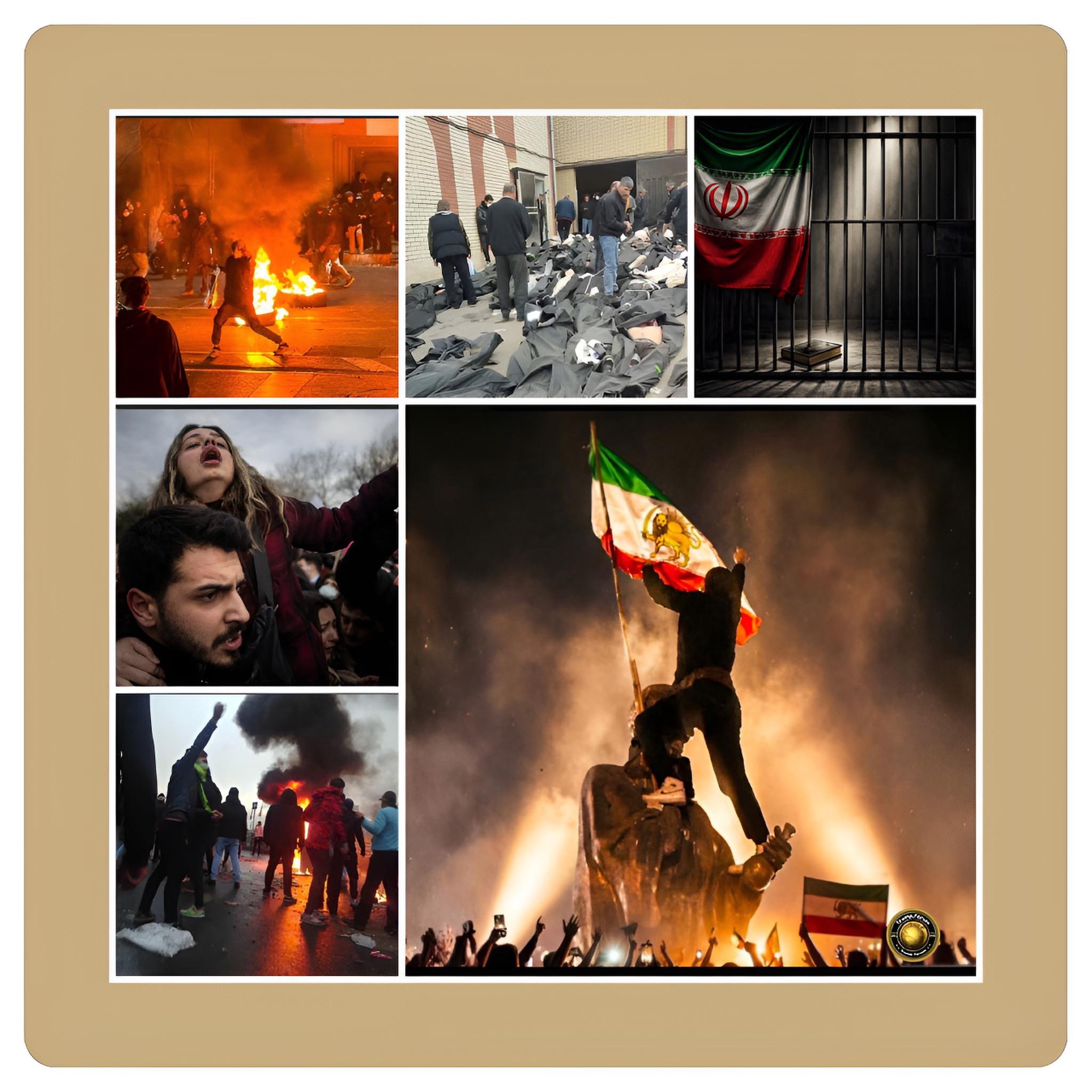

This economic behavior, rooted in rational self-interest, rapidly became a political uprising. Within days, the movement had metastasized from merchant complaints to university students, younger cohorts, and ordinary citizens demanding not merely economic relief but fundamental change. The chants evolved from "we want currency stabilization" to "Death to the whole regime."

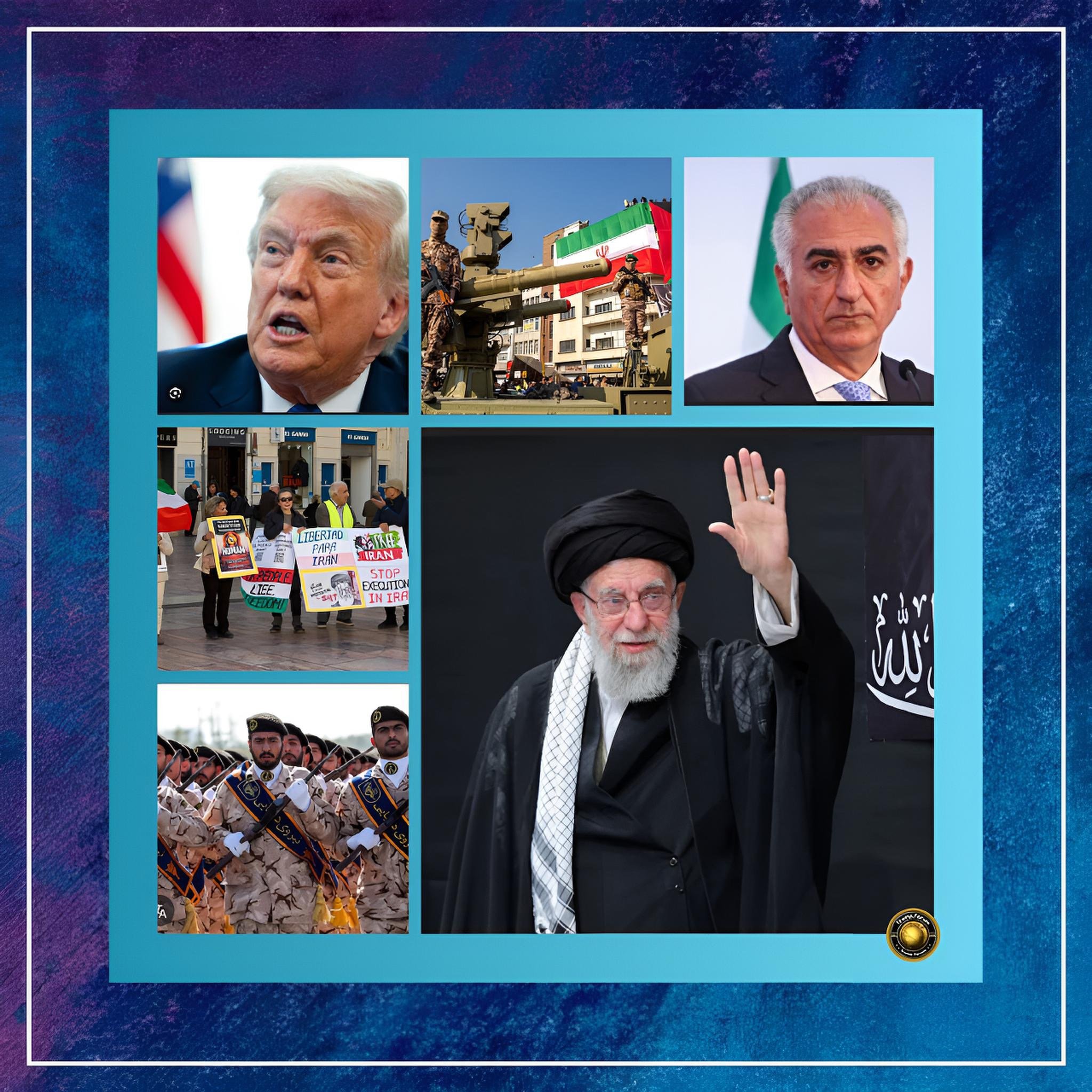

The regime's response reveals much about its true situation. Having presided over the systematic erosion of all non-coercive sources of power, Iran's leadership possessed essentially one tool remaining in its kit: violence. It was not a tool born of strength but rather of desperation. A confident, legitimacy-endowed regime might have attempted negotiation, policy concession, or the appointment of new officials. These moves would have been risky, but they would have acknowledged the legitimacy of the population's grievances and offered space for political maneuver. Instead, the regime chose the path of overwhelming massacre.

Between January 8 and 12, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and its allied security forces systematically murdered thousands of largely unarmed protesters. The death toll remains uncertain—ranging from approximately 2,677 conservatively documented deaths to estimates of 12,000 to 20,000 based on hospital records and medical facility reports. What is certain is that the scale was unprecedented in contemporary Iranian history. What is also certain is that it was organized from above rather than emerging from chaotic crowd suppression. Intelligence sources indicate clear orders to escalate lethally; hospital staff describe casualties consistent with execution-style killings; the coordination across multiple cities points to a centralized command decision.

The regime accompanied this bloodbath with a nationwide internet blackout that persists even as these words are written. This blackout serves multiple purposes simultaneously: it prevents protesters from coordinating; it obscures the scale of casualties from international observers; it limits the spread of images that might galvanize further resistance; and it grants the regime monopoly control over information. When the state controls the only information channel and can pressure families to falsify death certificates, the truth becomes whatever the state declares it to be.

Yet for all its brutality, the massacre has not solved any of the regime's underlying problems. The rial remains near historic lows. Inflation continues above 42 percent. Food prices are up 72 percent year-on-year. No policy change has been implemented that addresses the economic collapse that sparked the uprising.

This means that any temporary suppression of overt dissent will prove exactly that—temporary. The economic conditions that produced protest in December will produce protest again, whether in the coming weeks or in the coming months. The regime has dealt with a symptom of its disease through extreme violence but has not altered the disease itself.

This is where the regime's calculation becomes visible as an act of desperation rather than strength. Why choose mass murder when it solves nothing and creates its own costs?

The answer appears to lie in the regime's assessment that it is facing not a cyclical episode of discontent but an existential threat. The composition of the January movement—merchant, student, worker, and ordinary citizen united—suggested to regime commanders that this was different from earlier protests. The geographic breadth was unprecedented. The explicitly nationalist messaging ("Marg bar Gaza, marg bar Hamas; man tanha baraye Iran"—death to Gaza, death to Hamas, I have no interest but for Iran) directly repudiated the regime's foundational ideological commitment to pan-Islamic revolutionary struggle.

Intelligence assessments available to Ayatollah Khamenei and the IRGC leadership, combined with explicit military threats from the American president, appear to have convinced them that delay in implementing repression would only increase the challenge. A movement that was already broad and unified could only grow broader and more unified if tolerated for weeks or months. The regime thus made a choice that would have seemed unthinkable to a confident power: it chose to gamble that overwhelming brutality in the present would succeed where political flexibility might fail.

This gamble may prove correct in the short term. The streets of Iranian cities are indeed quieter in mid-January than they were in early January. The climate of fear is real and has deterred renewed mobilization. The regime has, in the narrowest sense, reasserted physical control over territory. From the perspective of the next few weeks, the massacre accomplished its immediate objective.

But in any longer time frame, this strategy becomes untenable. Societies do not indefinitely tolerate rule through terror from populations that possess no exit option and no prospect of material improvement.

The regime has now explicitly established that it will kill its own population on a mass scale rather than countenance challenge to its authority. This is information that changes how people calculate their relationship to the state. It eliminates any remaining space for ambiguity about the regime's nature. It validates every pessimistic assessment of the system's brutality and incapability of reform.

The regime has also, in choosing this path, acknowledged something crucial about its own weakness. A genuinely strong power facing genuine threat would not respond by massacring thousands. It would respond by addressing the sources of threat—by stabilizing the currency, by reducing the cost of living, by demonstrating responsiveness. That it instead chose massacre reveals that it has assessed these options as infeasible.

The regime cannot restore the rial without eliminating sanctions or accepting austerity that would contract living standards further. It cannot reduce inflation without addressing monetary expansion, which would require it to curtail spending on security apparatus and regional proxy networks. It cannot demonstrate responsiveness without accepting political constraints on its power. All of these options are, from the regime's perspective, equivalent to surrender.

Thus it has chosen violence instead. This choice may permit it to remain in power for months or even years. But it has done so by exhausting the last remaining sources of soft power and legitimacy that might have sustained the system through inevitable crises ahead.

The regime that emerges from January 2026 is not a system of governance but a security apparatus wearing the robes of state. Such arrangements can persist for surprisingly long periods, as the history of authoritarian rule demonstrates. But they are inherently unstable and ultimately fragile.

The true test will come not in the next few weeks, when fear still dominates public consciousness, but in the coming months, when economic conditions fail to improve and the psychological reality of living under a terrorizing state becomes the permanent condition rather than an acute crisis. At that point, the regime's choice to massacre in January will be revealed not as a demonstration of strength but as an act of terminal desperation—the final move of a power that has run out of alternatives.

History suggests that such moments often herald the beginning of the end, even if the end itself remains distant and uncertain.