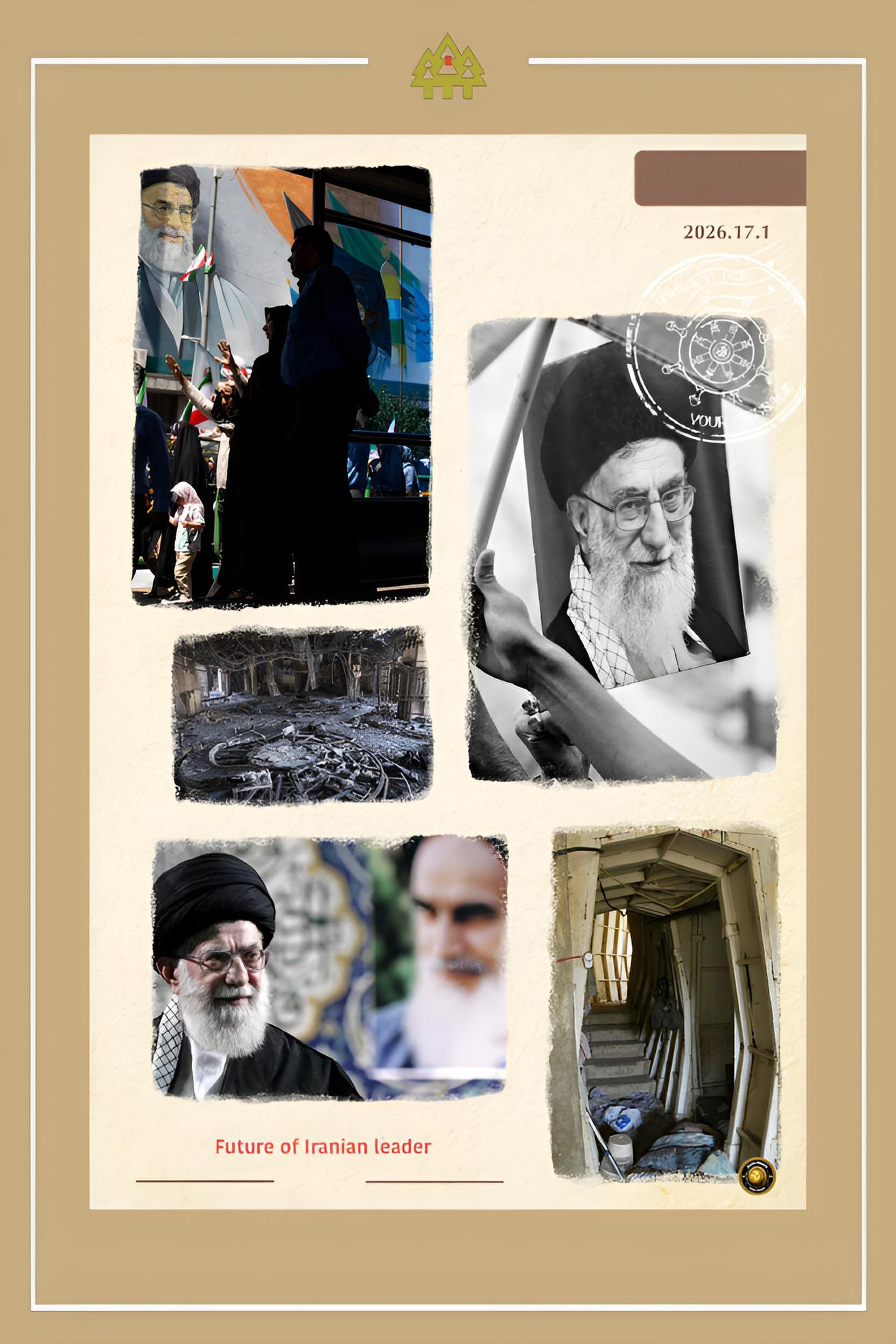

Marked man: scenarios for Iran’s Supreme Leader after Nasrallah’s death

Executive summary

A regime on borrowed time

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei enters 2026 as both the most powerful figure in Iran and perhaps the most vulnerable individual in the Middle East.

The precedents that hang over him are stark: Qassem Soleimani eliminated by a U.S. drone strike in 2020, Abu Bakr al‑Baghdadi hunted and cornered in Syria, and Hassan Nasrallah killed in a bunker some 60 feet beneath a residential block in Beirut on 27 September 2024. These events have demonstrated that deep underground facilities and the aura of revolutionary charisma no longer guarantee physical security.

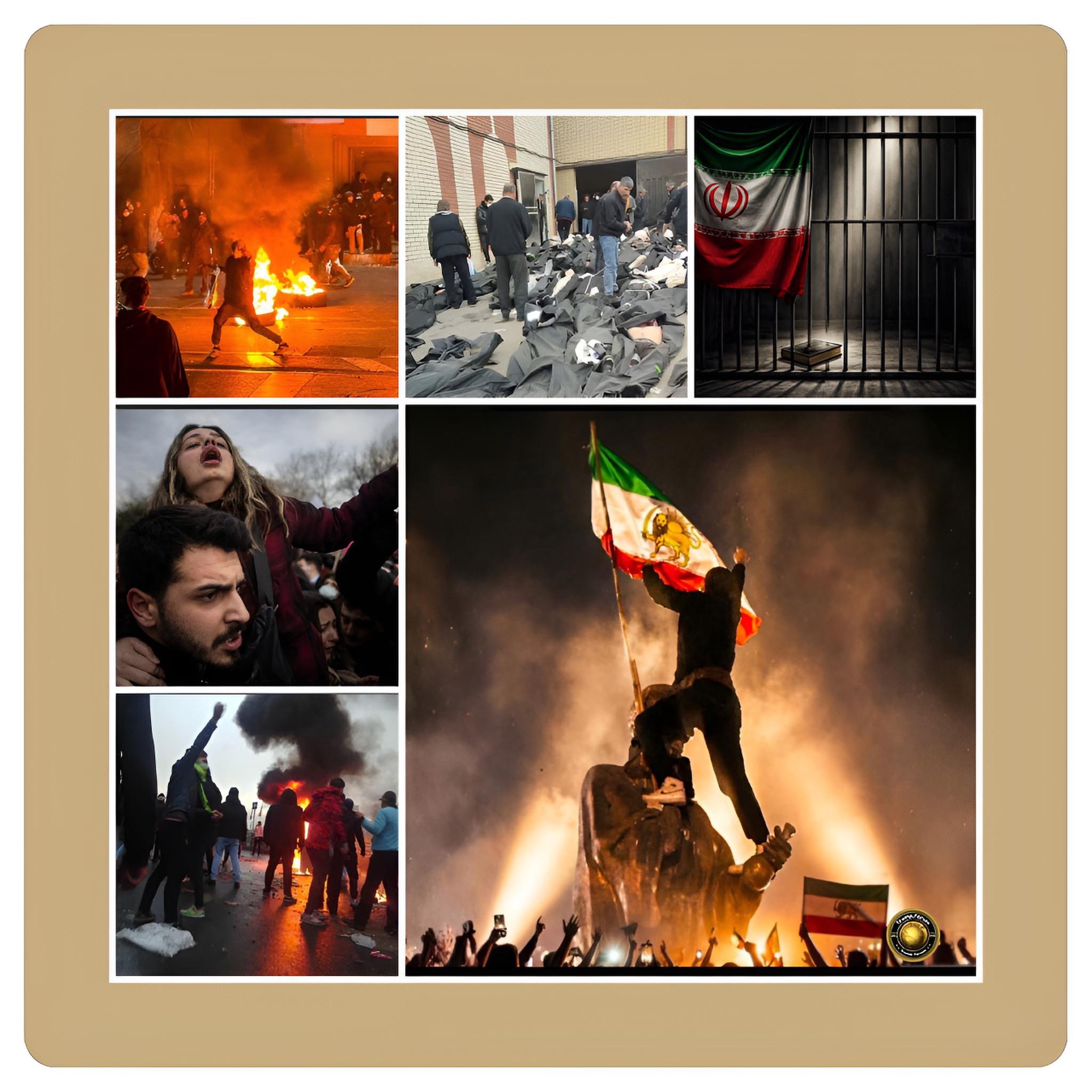

At the same time, Khamenei presides over a country in the throes of cumulative crises. The “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising of 2022–2023 shattered the regime’s social contract, even if it did not topple the Islamic Republic.

Subsequent waves of unrest have culminated in nationwide protests since late December 2025, met with a brutal crackdown that has killed thousands and triggered new U.S. sanctions and threats of intervention under President Trump.

Khamenei’s own succession plans have been thrown into disarray by the death of President Ebrahim Raisi in a 2024 helicopter crash, removing a key heir‑apparent and deepening factional maneuvering within the elite.

Strategically, Iran is more dangerous and more exposed than at any time since 1979. The nuclear program has pushed enrichment to 60% and amassed enough highly enriched uranium for several potential weapons within weeks, even after recent strikes and sabotage.

Yet Israel’s campaign culminating in Nasrallah’s assassination has exposed the limits of Iran’s “Axis of Resistance” strategy and shown that even its premier proxy can be decapitated in its deepest sanctuary.

The most likely trajectory for Khamenei in the near term is a combination of heightened physical seclusion, intensified domestic repression, and cautious regional recalibration.

He will seek to choreograph an orderly succession—probably around his son Mojtaba and a circle of loyal clerics and Revolutionary Guard commanders—while avoiding a direct war with the United States or Israel that could invite a decapitation strike.

Yet the very measures that promise regime survival in the short run—violence at home, nuclear brinkmanship, and proxy warfare abroad—also increase the risk that his final years are overshadowed by uncontrolled crisis rather than a managed transition.

Introduction

From untouchable to target: the shrinking sanctuary of Iran’s Supreme Leader

To understand “what next” for Iran’s Supreme Leader, one must recognize that Khamenei today lives in a different strategic universe from the one that sustained his rule for three decades. The Islamic Republic was long built on the premise that geography, deep bunkers, and layered deterrence through proxies would shield its top leadership from direct attack.

That assumption died in stages: when a U.S. drone destroyed Soleimani’s convoy outside Baghdad airport in January 2020; when Baghdadi’s last refuge in rural Syria was penetrated by special forces; and when Israeli jets in 2024 collapsed the subterranean headquarters where Nasrallah believed himself untouchable.

Layered on top of this is Khamenei’s deepening confrontation with his own people and with a re‑empowered White House willing to speak in the language of “rescue” and military readiness.

In early 2026, President Trump publicly warned that if Iranian forces continue to “violently kill peaceful protesters,” the United States is “locked and loaded and ready to go,” while Congress debates potential authorizations and constraints on the use of force.

Symbolically, Trump repeatedly invokes Soleimani and Baghdadi as examples of what Washington can do to enemies of the United States, a rhetorical move that Khamenei cannot safely ignore.

The question is therefore not only whether Khamenei can outlive this storm, but whether he can exit the stage on his own terms.

That question has three dimensions: the internal balance of power in Tehran, the evolving regional landscape after Nasrallah’s death, and the calculus of the United States and Israel as they weigh the costs and benefits of striking the person of the Supreme Leader.

History and current status

How Khamenei built an impregnable throne on crumbling foundations

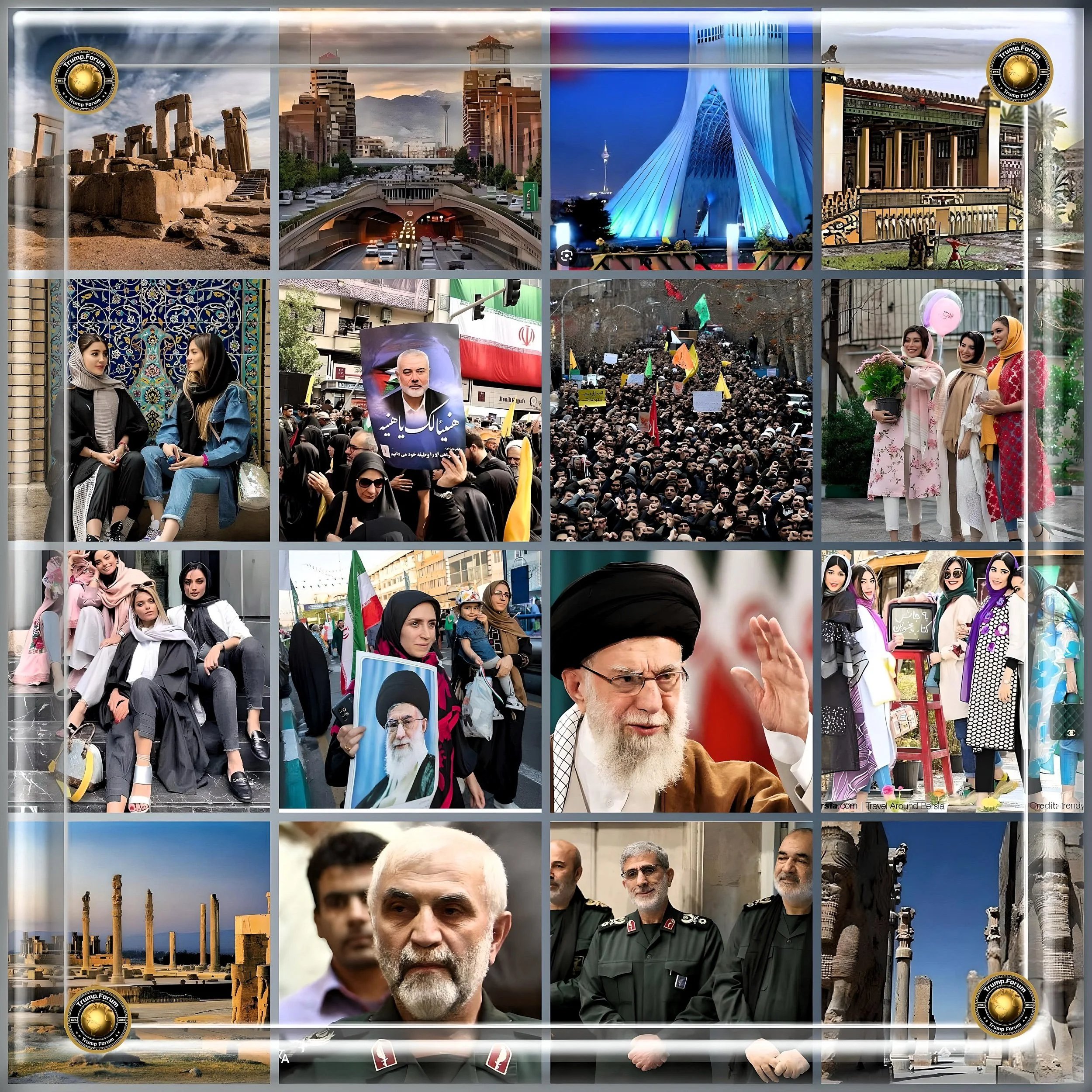

Khamenei has ruled since 1989, longer than any leader in modern Iranian history. His authority combines formal constitutional prerogatives—as Supreme Leader and commander‑in‑chief—with informal control over the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), intelligence services, state media, and the vetting institutions that sculpt every election.

Under his stewardship, the Islamic Republic has evolved into a highly securitized, ideologically rigid, and increasingly personalized system in which real power is concentrated in networks of clerics and Guards officers beholden to him.

Domestically, the turning point came with the Mahsa (Jina) Amini protests in 2022. Amini’s death in morality‑police custody ignited the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, which rapidly expanded from opposition to compulsory hijab to explicit calls for an end to the Supreme Leader’s rule and the Islamic Republic itself. Although the regime ultimately suppressed mass street mobilization through deadly force, mass arrests, and executions, it failed to restore the aura of legitimacy that once surrounded revolutionary authority.

Rights groups describe a “quiet revolution” in everyday life, as women refuse to comply with hijab rules and younger Iranians defy state narratives in their social and cultural choices.

In response, Khamenei doubled down on coercion. In 2024 the authorities launched the Noor Plan, a nationwide campaign to enforce veiling through intensified patrols, surveillance, and economic penalties.

By late 2025, new protests driven by economic collapse, corruption, and accumulated grievances erupted across dozens of cities. Security forces responded with live fire, mass detentions, and a near‑total information blackout, prompting the United States to impose fresh sanctions on senior officials and “shadow banking” networks in January 2026.

Khamenei’s personal health has been the subject of persistent speculation since at least his 2014 prostate surgery and rumored subsequent intestinal surgery.

Some reports have suggested episodes of serious illness or cognitive decline, while others stress that he continues to appear in public and deliver lengthy speeches. What can be stated with confidence is that he is of advanced age—mid‑80s—and that the political elite increasingly organize themselves around the inevitability of a succession struggle, even as the official line insists on his vigor.

On the nuclear front, Khamenei has overseen a dramatic expansion of Iran’s capabilities. After the collapse of the 2015 nuclear deal, Tehran gradually breached its limits, enriching uranium first to 20% and then to 60%, installing advanced centrifuges, and building up a stockpile that international watchdogs now judge sufficient for multiple weapons within weeks if further enriched to weapons‑grade.

Israel and, more recently, U.S. strikes and cyber‑operations have damaged several facilities and set back portions of the program, but they have not reversed Iran’s acquisition of a latent nuclear weapons option.

Regionally, Khamenei’s signature achievement has been the construction of the “Axis of Resistance,” a network of allied militias and political movements—Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas and Islamic Jihad in Gaza, armed groups in Iraq and Syria, and the Houthis in Yemen—designed to surround Israel and project Iranian influence without inviting direct interstate war.

For decades, Hezbollah under Nasrallah was the crown jewel of this architecture: a disciplined, heavily armed movement on Israel’s northern border that deterred large‑scale strikes on Iran itself.

Nasrallah’s assassination in September 2024 gravely weakened that deterrent shield and forced Tehran to rethink how it deters Israel from attacking Iranian territory and nuclear infrastructure.

Key developments reshaping Khamenei’s position

From Soleimani to Nasrallah: the chain of blows that cornered Tehran

Four recent developments have fundamentally altered the strategic environment in which Khamenei operates.

First, the death of Qassem Soleimani in 2020 and President Ebrahim Raisi in 2024 has robbed the regime of the two figures most carefully groomed to manage succession and maintain elite cohesion after Khamenei.

Soleimani was the charismatic architect of Iran’s regional influence; Raisi, an ultraconservative jurist, was widely seen as a leading contender for Supreme Leader and for chairmanship of the Assembly of Experts, the body constitutionally mandated to choose the next leader. Their absence has increased the likelihood of factional infighting among Guards commanders and clerics once Khamenei dies.

Second, the March 2024 election to the Assembly of Experts consolidated hardline control over this crucial institution. Moderates and relative pragmatists were barred or sidelined, while Raisi and a cadre of loyalists secured seats, positioning them—before his death—to influence the choice of Khamenei’s successor. With Raisi gone, attention has shifted to Mojtaba Khamenei, the Supreme Leader’s second son and de facto gatekeeper, along with figures such as Alireza Arafi.

Mojtaba lacks formal religious standing and carries the stigma of potential hereditary succession, but he commands extensive networks within the IRGC and security apparatus.

Third, Nasrallah’s killing in a fortified underground headquarters in Beirut dramatically changed the regional balance. Israel’s use of bunker‑buster munitions to collapse a command center 60 feet below an apartment block—and then publicly release footage of the operation—sent a clear message about its capability and will to decapitate key leaders of the “Axis of Resistance.”

Analysts across the region note that this strike has both weakened Iran’s deterrent posture and demonstrated the vulnerability of even the most heavily protected command sites, including those believed to house Iran’s own top leadership.

Fourth, the eruption of nationwide protests in late 2025 has forced Khamenei into a more explicit confrontation with Washington. The new wave of unrest, driven by economic collapse, currency freefall, and anger at corruption and repression, prompted an especially bloody crackdown, with outside groups estimating thousands of deaths.

The Trump administration responded not only with sanctions on officials and financial networks, but also with rhetoric suggesting readiness to “rescue” protesters and to use force if killings continued. Congressional briefing papers explicitly discuss options ranging from enhanced internet support to covert action and, at the outer edge, military strikes.

Latest facts and concerns

Bunkers, bombs, and breakdown: the risks closing in on Khamenei

The immediate concerns surrounding Khamenei’s future fall into four broad categories: physical security, internal political stability, nuclear risk, and regional deterrence.

On physical security, Nasrallah’s fate casts a long shadow. The Israeli strike that killed him relied on prolonged intelligence collection and deep penetration of Hezbollah’s security, reportedly aided by an informant.

The message is that no bunker is invulnerable, no chain of command impermeable. Iranian and Western analysis since then has increasingly focused on the possibility that, in a major regional war or in response to certain thresholds—such as an imminent Iranian nuclear breakout—Israel or even the United States might contemplate a direct strike on the Supreme Leader or his narrow command circle. This does not mean such an operation is imminent or likely, but it means Khamenei must now plan as if it cannot be categorically excluded.

Internally, the death of Raisi has profoundly complicated succession engineering. With one major rival removed from the field, Mojtaba’s profile has risen, but so have concerns among insiders that an overtly dynastic handover could discredit the regime’s anti‑monarchical founding narrative and provoke further unrest, including within the clerical establishment.

Rumors and orchestrated media hints highlighting Mojtaba’s supposed anti‑corruption zeal suggest a deliberate effort to launder his image and present him as a necessary savior, even as critics warn that such a move would deepen elite fractures rather than resolve them.

The nuclear program is another source of acute concern. International monitoring indicates that by mid‑2025 Iran possessed over 400 kilograms of uranium enriched to 60%—a quantity sufficient, if further enriched to 90%, for multiple nuclear warheads.

Some assessments estimate that Iran could produce enough weapons‑grade material for five to eight bombs in a matter of one to two weeks, assuming full use of its advanced centrifuge cascades at Natanz and Fordow.

At the same time, satellite imagery and technical analyses suggest that recent Israeli and U.S. operations during and after a short but intense “12‑day war” in 2025 inflicted significant damage on key enrichment facilities and air defenses, partially degrading Iran’s breakout capacity and complicating its ability to protect nuclear sites from further attack.

Regionally, with Hezbollah decapitated and battered, Iran must increasingly rely on a more diffuse network of proxies and partners—particularly the Houthis in Yemen and emerging militias in Syria—to maintain pressure on Israel and U.S. assets while avoiding direct war.

This decentralization reduces Tehran’s dependence on any single actor but also dilutes control and complicates coherent strategy. Furthermore, Gulf Arab states and other regional governments, while still wary of Iran, now increasingly view Israel as a destabilizing actor and have opened quiet diplomatic channels with Tehran to avoid escalation spilling onto their soil.

Cause‑and‑effect analysis

When deterrence backfires: how Khamenei’s grand strategy made him vulnerable

Khamenei’s predicament is the product of long‑term choices converging with immediate shocks. His core strategic bet since the 1990s has been that exporting the revolution via proxies, pursuing a latent nuclear capability, and suppressing dissent at home would guarantee regime survival and elevate Iran’s status.

Those policies have produced undeniable gains in regional leverage, but at three systemic costs that now feed back into his personal vulnerability.

First, the proxy strategy has created enemies who are both powerful and increasingly willing to strike high‑value targets. Israel’s systematic campaign against Iran’s regional network—assassinating militia leaders, bombing weapons depots, and finally killing Nasrallah—was justified in Tel Aviv’s calculus precisely by the expansion of Iran’s missile and drone capabilities and the perception that Tehran was approaching a nuclear threshold.

By using Hezbollah as a forward deterrent, Khamenei made Hezbollah’s leadership a legitimate military target; by pushing Hezbollah into a more open confrontation during the Gaza war and thereafter, he raised the stakes to the point where Israel judged that decapitation was worth the risk. The same logic applies, at least in principle, to Khamenei himself in the event of full‑scale war.

Second, the nuclear program has shifted the locus of deterrence from diffuse ambiguity to measurable timelines. In the era of limited enrichment, the risk of a preventive strike on top leadership seemed distant; Western and Israeli planners could assume years, not weeks, before Iran could assemble a bomb.

By compressing the breakout window to days or weeks, Tehran has forced its adversaries to plan for highly time‑sensitive contingencies in a crisis. In those scenarios, decapitating the decision‑maker who might order a nuclear dash—or, in some scenarios, order a massive regional escalation in response to strikes—appears as one option within a larger set of escalatory moves.

Third, relentless domestic repression has eroded the regime’s legitimacy and narrowed Khamenei’s political options. The repeated use of lethal force against protesters, executions of dissidents, and securitized social policies such as the Noor Plan have convinced a broad swathe of the Iranian population that incremental reform is impossible.

This, in turn, bolsters those within the U.S. and regional policy circles who argue that only maximal pressure—including the threat of force—can induce behavioral change. President Trump’s promise to “come to the rescue” of Iranian protesters and his administration’s comparison of new sanctions architects to past “terrorist” targets are themselves effects of a narrative in which Khamenei is cast not as a conventional head of state but as the mastermind of a criminal enterprise.

The feedback loop is vicious. The more Khamenei relies on coercion at home, the easier it becomes for external actors to portray strikes against his regime as morally justified. The more he leans on proxies and a nuclear shield to deter those actors, the more they are incentivized to demonstrate that no shield is impenetrable.

Nasrallah’s death is the clearest single illustration of this dynamic: a tactical success for Israel that simultaneously undermines Iran’s long‑term security calculus and intensifies Khamenei’s personal sense of being hunted.

Future steps: plausible trajectories

Three endgames for the Islamic Republic’s last patriarch

Khamenei’s future is best understood not as a single forecast but as a set of interlocking scenarios, all of which he and his circle must now plan for. Three stand out as the most plausible in the next one to five years.

First Scenario

The first and most likely scenario is a “securitized continuity.”

In this pathway, Khamenei survives physically, perhaps in increasing seclusion and under elaborate protective measures, and continues to rule through a tightened inner circle of IRGC and clerical loyalists.

Domestic policy remains repressive, with periodic concessions on economic management but no meaningful political opening.

The nuclear program continues to hover just short of weaponization, using its bargaining power to extract concessions while avoiding the single step that might trigger an all‑out strike.

Succession is gradually choreographed around Mojtaba Khamenei, possibly embedded within a leadership council framework constructed by the Assembly of Experts to give a veneer of institutional legitimacy.

Second Scenerio

The second scenario is “managed succession under crisis.” Here, a health crisis or sudden escalation forces an expedited activation of constitutional mechanisms.

The Assembly of Experts, under intense pressure from the IRGC, would be compelled to name a successor rapidly, perhaps first in the form of a temporary leadership council.

Mojtaba, Arafi, and a small group of senior Guards officers would likely dominate this body, but the need to placate different factions could yield compromises that dilute any one figure’s authority.

Under such conditions, the risk of internal purges, defections, or localized uprisings would spike, particularly in regions already alienated by economic deprivation or ethnic discrimination.

Khamenei’s own final role in this scenario would depend on whether he has the time and capacity to bless a successor or whether his death—or incapacitation—precedes a settled deal.

Third Scenario

The third and least likely, but most dramatic, scenario is “decapitation amid regional war.”

This would involve a sequence in which Iran either crosses clear nuclear thresholds or launches large‑scale attacks via proxies or directly on Israel or U.S. forces, prompting a regional conflict far beyond current levels of violence. In that context, Washington or Tel Aviv might calculate that striking Khamenei and his command nucleus—much as Soleimani and Nasrallah were targeted—would shorten the war or shatter the regime’s coordination.

The operational feasibility of such a strike is no longer a theoretical question; the political calculus remains the principal barrier. Even those in Washington who advocate maximal pressure often warn that the aftermath of a leaderless, nuclear‑capable Iran could be more dangerous than the status quo.

Under all scenarios, the United States and its allies will continue to face hard choices. Expanding covert and overt support for Iranian protesters carries moral weight but risks feeding the regime’s narrative of foreign conspiracy and justifying even more violent repression.

Targeting the nuclear program and IRGC proxies may slow Iran’s regional ambitions but can also strengthen hardliners in Tehran and narrow the space for any future accommodation.

The question “what next for Khamenei?” is inseparable from “what next for U.S. strategy?”—and neither can be answered without acknowledging the gap between the desire to punish an oppressive regime and the dangers of regional chaos or war.

Conclusion

The man who became Iran’s single point of failure

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei stands at the convergence of three implosions: of a decaying revolutionary ideology at home, of a regional deterrent architecture punctured by Nasrallah’s death, and of a nuclear diplomacy process that has given way to cycles of escalation and sabotage. He remains, for now, the arbiter of Iran’s fate, but his margins for maneuver shrink with each protest, each targeted killing of an ally, and each increment of uranium enrichment.

In practical terms, the most probable outcome is that Khamenei dies in office after a period of mounting seclusion, having done everything in his power to engineer a hardline succession that preserves the system he built. Yet the forces he has unleashed—social radicalization from below, militarization of regional rivalries, and proliferation risks at the nuclear level—make a controlled denouement far from guaranteed.

History is rarely kind to leaders who rule too long, personalize power too completely, and leave too little oxygen for peaceful change.

In that sense, Khamenei is indeed a marked man—not only in the crosshairs of rival intelligence services, but in the judgment of a generation of Iranians for whom his rule has come to symbolize stagnation, repression, and missed possibilities.

Whether his final chapter is written by an assassin’s warhead, a doctor’s note, or a quiet communiqué from the Assembly of Experts, the deeper story will be the same: a revolutionary state that, in trying to insulate its leader from accountability, ultimately made him the single point of failure for an entire system.