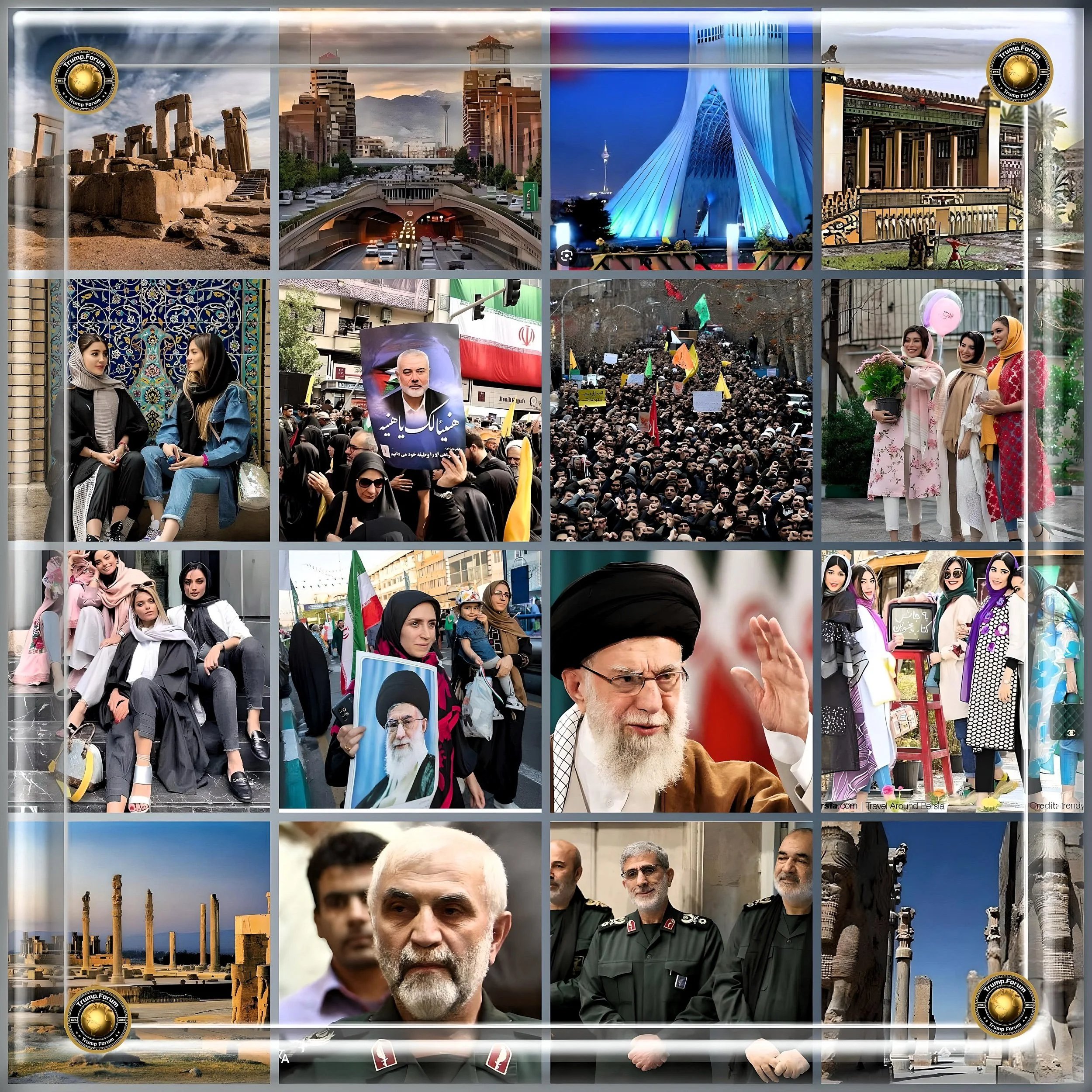

Gulf.Inc : Iran’s Rich History: From Ancient Persia to Modern Islamic Republic

Introduction

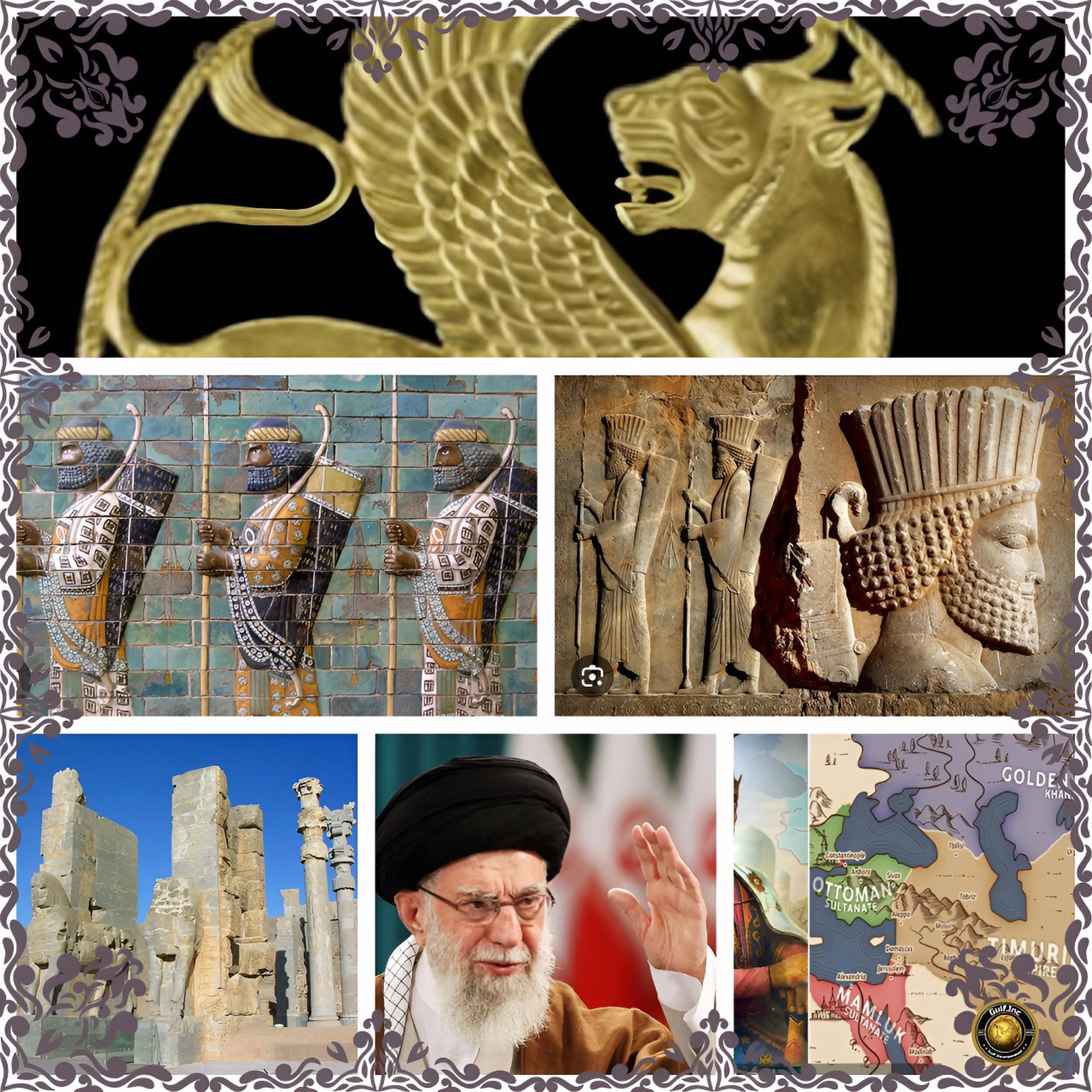

Ancient Persian Empires: The Foundation of Iranian Civilization

The history of Iran, historically known as Persia, spans thousands of years and represents one of the world’s oldest continuous civilizations.

The first major Iranian empire, the Achaemenid Empire, was founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BCE.

This empire quickly became the largest in history, spanning 5.5 million square kilometers from the Balkans and Egypt in the west to the Indus Valley in the southeast.

Under Cyrus’s leadership, the Persian Empire defeated the mighty city of Babylon in 539 BCE, a victory that marked the true beginning of Persian imperial dominance.

The Achaemenid dynasty established a successful model of centralized bureaucratic administration, implemented multicultural policies, built complex infrastructure, including road systems and postal services, and maintained a large professional army.

These advancements would later inspire similar governance styles in subsequent empires. Notable rulers of this dynasty included Cyrus I, Cambyses I, Cyrus II (the Great), Cambyses II, and later Darius I, who excelled as an administrator and secured the empire’s borders.

Following the Achaemenid Empire’s fall to Alexander the Great in 330 BCE, Iran experienced rule under the Seleucid Dynasty (312-63 BCE), which introduced Hellenistic influence while preserving Persian traditions.

This was followed by the Parthian Empire (247 BCE- 224 CE), which served as a cultural bridge between Rome and Asia and facilitated East-West trade.

The Sasanian (or Sassanid) Empire (224-651 CE) emerged when Ardashir I overthrew the Parthian Empire.

Under the Sasanians, Iran was once again a leading world power for over 400 years, alongside its neighboring rival, the Roman and later Byzantine Empires.

The Sasanians created a distinctive Iranian self-image with new trappings of kingship, splendid royal art, centralized administration, and an aggressive military policy.

They called their empire “Erânshahr” (“Dominion of the Aryans” or “of Iranians”). The Sasanian era is considered one of the most important and influential periods in Iranian history, representing the highest achievement of Persian civilization before the Muslim conquest.

Islamic Era and Medieval Dynasties

The Arab conquest in 651 CE ended the Sasanian Empire and brought Islam to Iran. Persian cultural influence remained strong despite this political change, transforming the Islamic conquest into a Persian renaissance.

Much of what later became known as Islamic culture, architecture, writing, and other skills were borrowed from the Sasanians and spread throughout the broader Muslim world.

Following the Islamic conquest, Iran experienced a period of fragmentation (651-1501 CE) under various dynasties, including the Buyids, Samanids, and Seljuks.

This period sparked a Persian literary renaissance, notably with creating the epic poem Shahnameh, and saw cultural integration with Islam.

The Rise of Modern Iran: Safavid to Pahlavi Dynasties

Safavid Dynasty (1501-1736)

The Safavid dynasty, established in 1501, is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history.

Under Shah Ismail I, the Safavids established Twelver Shi’a Islam as the official religion of Persia, marking one of the most crucial turning points in Islamic history.

This decision continues to shape Iran’s religious and political identity.

The Safavids originated from a Sufi order established in Ardabil, in the Iranian Azerbaijan region.

From their base, they established control over parts of Greater Iran. They reasserted the region's Iranian identity, becoming the first native dynasty since the Sasanian Empire to establish a national state officially known as Iran.

At their height, the Safavids controlled all of modern Iran, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Armenia, eastern Georgia, parts of the North Caucasus, Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan, as well as parts of Turkey, Syria, Pakistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

The Safavid Empire reached its zenith under Shah Abbas I (reigned 1587-1629). Abbas revitalized the empire by modernizing the military, removing traditional chieftains from command, and integrating foreign expertise.

His reign saw the flourishing of arts and architecture, with the city of Eşfahān becoming the cultural heart of the empire. The Safavid government encouraged intellectual pursuits and fostered a vibrant literary culture.

Qajar Dynasty (1794-1925)

Following the Safavid decline, Iran experienced brief rule under the Afsharid (1736-1796) and Zand (1751-1794) dynasties before the rise of the Qajar dynasty.

The Qajars ruled from 1794 to 1925 and played a pivotal role in Iran's unification.

However, during this period, Iran lost significant territory to the Russian Empire in the Caucasus, comprising modern-day eastern Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan, and Armenia.

Despite these territorial losses, Qajar Iran maintained relative political independence but faced significant challenges to its sovereignty, predominantly from the Russian and British empires.

Foreign advisers became powerbrokers in the court and military, and the European powers eventually partitioned Qajar Iran in the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention, carving out Russian and British influence zones.

Pahlavi Dynasty (1925-1979)

The Pahlavi dynasty was founded in 1925 by Reza Shah, a non-aristocratic Iranian soldier who took power following the 1921 coup d’état.

The dynasty replaced the Qajar dynasty and ruled Iran until the Islamic Revolution of 1979. The Pahlavis espoused Iranian nationalism rooted in the pre-Islamic era, particularly based on the Achaemenid Empire.

Reza Shah had initially planned to declare the country a republic, similar to what Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had done in Turkey, but abandoned the idea due to British and clerical opposition.

The dynasty ruled Iran for 28 years as a form of constitutional monarchy from 1925 until 1953, and following the overthrow of the elected prime minister, for a further 26 years as a more autocratic monarchy.

The Iranian Revolution and Islamic Republic

The Iranian Revolution 1979 transformed Iran from an absolute monarchy under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

The revolution was fueled by widespread perceptions of the Shah’s regime as corrupt, repressive, and overly reliant on foreign powers, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom.

Many Iranians felt that the Shah’s government was not acting in the best interests of the Iranian people and was too closely aligned with Western interests at the expense of Iranian sovereignty and cultural identity.

The Shah’s government finally occurred on February 11, 1979, when the Supreme Military Council declared itself “neutral in the current political disputes… to prevent further disorder and bloodshed.”

All military personnel were ordered back to their bases, effectively giving Khomeini control of the country.

Revolutionaries took over government buildings, TV and radio stations, and palaces of the Pahlavi dynasty, marking the end of the monarchy in Iran.

The revolution included the approval of a new theocratic constitution in December 1979, whereby Ayatollah Khomeini became Supreme Leader.

Populist and Islamic economic and cultural policies replaced Iran’s modernizing, capitalist economy.

Industries were nationalized, laws and schools were Islamicized, and Western influence was restricted.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: From Humble Origins to Supreme Leader

Early Life and Education

Ali Hosseini Khamenei was born on April 19, 1939, in the holy city of Mashhad in northeastern Iran. He was born into a clerical family of modest means, the second son among eight children.

His father, Seyyed Javad Khamenei, was a respected religious scholar of Azeri descent who had studied in Najaf, Iraq, one of the holiest cities in Shi’a Islam.

Despite being a well-known religious figure, Khamenei’s father led an ascetic lifestyle, unconcerned with materialistic goods or worldly affairs.

Khamenei often describes his childhood as poverty, which was common for clerical families at that time.

He recalls growing up in a small house with only one room and a gloomy basement, where his family sometimes had nothing but bread and raisins for supper.

Despite these economic hardships, Khamenei attributes his early life’s enrichment to his close-knit family and their shared love for Islam, literature, and poetry.

At the age of four, Khamenei and his older brother Mohammad were sent to maktab, the traditional primary schools of that time, to learn the alphabet and the Holy Quran.

He later attended a religious primary school called “Dar ut Ta’lim e Diyanati”.

After completing his primary education, Khamenei pursued his studies at the theological seminary in Mashhad under the supervision of his father and other religious scholars.

Khamenei began his advanced religious studies at the exceptionally young age of eighteen.

In 1957, he made a pilgrimage to the holy shrines in Iraq and studied briefly in Najaf under eminent scholars such as Ayatollah Hakim and Ayatollah Shahrudi.

However, in 1958, he returned to Iran to continue his advanced studies in the holy city of Qom, respecting his father's wish.

He studied under great scholars and grand ayatollahs, including Ayatollah Borujerdi and Ruhollah Khomeini, who would later lead the Iranian Revolution.

Political Activities and Revolutionary Role

Khamenei’s political consciousness was first awakened at 13 when he heard a fiery speech by Nawwab Safavi, a brave cleric who spoke against the Shah’s anti-Islamic policies.

As a young cleric, Khamenei became actively involved in protests against the monarchy of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Due to his political activities, he was imprisoned several times by Iran’s security services.

During the Iranian Revolution, Khamenei remained closely associated with Ayatollah Khomeini.

Immediately after Khomeini’s return to Iran in 1979, Khamenei was appointed to the Revolutionary Council.

He subsequently held several important positions in the newly established Islamic Republic, including deputy minister of defense and Khomeini’s representative on the Supreme Defense Council.

Briefly, he commanded the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

In 1981, Khamenei was the target of an assassination attempt when a bomb hidden in a tape recorder exploded while he was addressing a mosque.

The attack left him with serious injuries and permanently paralyzed his right arm.

Following the assassination of President Mohammad Ali Rajai and Prime Minister Mohammad Javad Bahonar in August 1981, Khamenei ran for the presidency and won with 95 percent of the votes.

Rise to Supreme Leadership

Khamenei was president of Iran from 1981 to 1989, coinciding with the Iran-Iraq War.

As president, he sought to cement the clerical establishment’s control of key organs of power, often clashing with more left-leaning figures.

However, during this time, the presidency was largely ceremonial, with most executive authority vested in the prime minister.

The death of Ayatollah Khomeini on June 3, 1989, marked a crucial turning point for Iran.

Khomeini’s long-time designated successor, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, had been sidelined three months earlier due to his calls for more political pluralism.

The Assembly of Experts designated Khamenei as Iran’s new Supreme Leader, despite Khamenei initially arguing he was not qualified for the position.

At the time of his appointment, Khamenei held only the middle-ranking clerical position of hojatoleslam, not the higher rank of ayatollah that was traditionally required for the position of Supreme Leader.

This led to modifications in the constitution to allow him to assume the role.

The constitutional changes stated that it was more important for the office holder to be “aware of the times” and politically minded than to derive authority solely from specific religious qualifications.

Khamenei was officially elected as the new Supreme Leader by the Assembly of Experts on June 4, 1989.

Despite his initial protestations of unworthiness, saying “my nomination should make us all cry tears of blood,” he accepted the position.

Since then, Khamenei has worked to consolidate his power, tightening his grip on the country’s political, military, and security apparatus.

Iran’s Nuclear Program and International Tensions

Origins and Development of Iran’s Nuclear Program

Iran’s nuclear ambitions began under the rule of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, with support from the United States and Western Europe.

In 1957, Iran and the US signed a civil nuclear cooperation agreement as part of President Dwight Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” program.

This led to the construction of Iran’s first nuclear research facility in Tehran.

In 1967, the Tehran Research Reactor went critical, initially running on highly enriched uranium fuel provided by the US.

In the mid-1970s, the Shah expanded Iran’s nuclear energy ambitions, establishing the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) in 1974 and announcing plans to produce 23,000 megawatts of electricity from nuclear power plants over 20 years.

Contracts were signed with Western firms, including a $1 billion stake in a French uranium enrichment consortium and an agreement with West Germany’s Kraftwerk Union to build two reactors at Bushehr.

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, Iran’s nuclear program was temporarily frozen as the new government terminated contracts with Western firms.

However, the program was secretly resumed during the 1980s Iran-Iraq War.

In the late 1990s, Iran launched a nuclear weapons research program codenamed the AMAD Project, aimed at designing and building an arsenal of five nuclear warheads by the mid-2000s.

International Concerns and Sanctions

In 2002, revelations about Iran’s secret nuclear projects spurred years of diplomacy and pressure aimed at curbing the program.

The international community, particularly Western powers, expressed concerns that Iran’s uranium enrichment activities could be directed toward developing nuclear weapons, despite Iran’s insistence that its program was for peaceful purposes only.

Over the years, sanctions have taken a serious toll on Iran’s economy and people.

The United States has led international efforts to use sanctions to influence Iran’s policies, including its uranium enrichment program.

The UN Security Council passed several resolutions imposing sanctions on Iran following reports by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) regarding Iran’s non-compliance with its safeguards agreement.

These sanctions were designed to block the transfer of weapons, components, technology, and dual-use items to Iran’s nuclear and missile programs; target select sectors of the Iranian economy relevant to its proliferation activities; and induce Iran to engage constructively in discussions with major world powers.

The Nuclear Deal and Its Aftermath

After years of negotiations, Iran and six world powers (the P5+1: the United States, the United Kingdom, Russia, France, China, plus Germany) concluded the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal, in 2015.

The agreement aimed to limit Iran’s nuclear activities and increase transparency through expanded monitoring by the IAEA.

Under the JCPOA, Iran agreed not to produce either highly enriched uranium or plutonium that could be used in a nuclear weapon.

The accord limited Iran's ability to operate a number and type of centrifuges, the level of enrichment, and the size of its stockpile of enriched uranium.

In return, the EU, United Nations, and United States committed to lifting their nuclear-related sanctions on Iran.

However, in 2018, the United States under President Donald Trump withdrew from the deal and reinstated sanctions.

A year later, Iran began decreasing its compliance with the agreement, and by 2020, Iran announced it would no longer observe any limits set by the JCPOA.

This has brought Iran closer to nuclear threshold status.

Regional and Global Security Concerns

Many foreign policy experts warn that if Iran were to acquire nuclear weapons, it would be broadly destabilizing for the Middle East and nearby regions.

A primary concern is that Iran’s possession of nuclear weapons would pose a significant, perhaps existential threat to Israel.

This worry has driven Israel’s strong opposition to Iran’s nuclear program, culminating in military strikes against Iranian nuclear facilities in June 2025.

There is also concern that Iran’s acquisition of nuclear weapons would incentivize other countries in the region, particularly Saudi Arabia, to pursue their atomic programs, potentially catalyzing a dangerous nuclear arms race.

Saudi Arabia has indicated that if diplomatic efforts fail to prevent Iran from producing a nuclear weapon or enriching uranium beyond acceptable levels, it would be compelled to acquire its nuclear deterrent.

The international community remains divided on how to address Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

While Western powers generally oppose Iran’s nuclear program, countries like Russia and China have provided political and diplomatic cover for Iran.

This division complicates efforts to generate multilateral diplomatic pressure on Tehran.

In June 2025, the IAEA Board of Governors passed a resolution indicating that Iran was not adhering to its obligations regarding international nuclear safeguards.

This decision prompted Iran to announce plans to build a new uranium enrichment facility and upgrade its nuclear centrifuges at Fordow, further escalating tensions with the international community.

Conclusion

Iran at a Crossroads

Iran’s rich history, spanning many centuries, has shaped its national identity and regional aspirations.

From the glorious days of the Persian Empire to the establishment of the Islamic Republic, Iran has maintained its cultural continuity while adapting to changing political realities.

The rise of Ayatollah Khamenei from humble beginnings to becoming one of the most powerful figures in the Middle East exemplifies the complex interplay of religious authority and political power in modern Iran.

The ongoing dispute over Iran’s nuclear program represents a significant challenge not only for Iran but for regional and global security.

As Iran continues to develop its nuclear capabilities despite international pressure, the country finds itself at a crossroads between isolation and integration into the global community.

The decisions made by Iran’s leadership and the international response to its nuclear ambitions will have profound implications for the future of the Middle East and beyond.

Iran has demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability to external pressures and internal challenges throughout its long history.

Whether the current tensions over its nuclear program will lead to further confrontation or eventual reconciliation remains one of the most pressing questions in international relations today