US Keeps Iran’s Exiled Prince on Standby as Protesters Die: Secret Meeting Reveals ‘Break Glass’ Transition Plan

Executive summary

A prince in Washington’s shadows: the conditional bet on Iran’s exiled heir

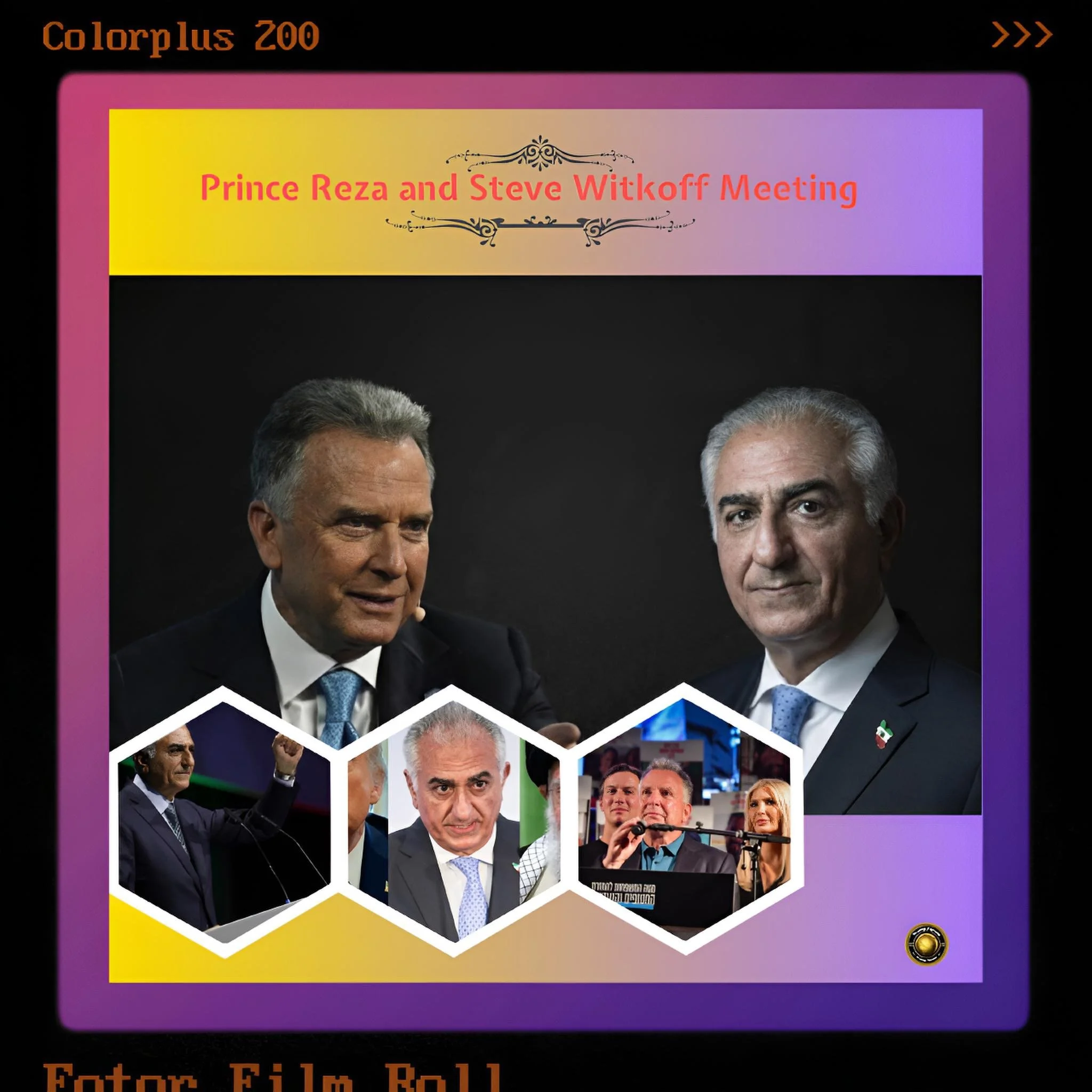

The clandestine meeting between White House envoy Steve Witkoff and exiled Iranian crown prince Reza Pahlavi, held amid the most serious nationwide protests Iran has seen in years, signals a qualitative shift in how Washington thinks about regime change and political transition in Tehran.

Publicly, the Trump administration continues to insist that Iranians must decide their own future and that all options remain on the table, from diplomacy to force.

Privately, however, the evidence suggests that Pahlavi is being treated as a contingency asset: a potential transitional figure, a political symbol to amplify protestors’ morale, and a lever against the Islamic Republic in parallel to ongoing back-channel contacts with Tehran.

There is, at present, no formal, codified “US plan for Prince Reza” comparable to an occupation blueprint or a public doctrine.

What exists instead is an evolving, layered posture: exploratory political coordination with Pahlavi; careful testing of his social base and legitimacy; integration of his role into broader options for coercive diplomacy; and hedging against the risks that overt American sponsorship could discredit him inside Iran or fracture an already fragmented opposition.

The net effect is that Pahlavi is neither being groomed as a straightforward restoration monarch nor discarded as an irrelevant exile. He is being positioned by both himself and key figures in Washington as one plausible node in a potential transition, to be activated if and only if the regime’s internal cohesion starts to collapse under protest, economic strain, and external pressure.

Introduction

From exile to option: why Reza Pahlavi is back on the US policy radar

The question “What is the US plan for Prince Reza?” arises at the intersection of three dynamics: a Trump administration that openly embraces regime-pressure tactics; a protest wave that has shaken nearly 200 cities across Iran; and an exiled crown prince who has spent decades on the margins but now sees an opening to recast himself as a democratic transitional leader rather than a nostalgic monarch.

Between a prince and a hard place: how Washington is really thinking about Reza Pahlavi

Steve Witkoff’s secret weekend meeting with Pahlavi, described by US officials as the first high-level contact between the administration and the Iranian opposition since the current unrest began, is a pivotal data point. It follows a series of statements in which Pahlavi has urged Iranians to escalate their protests, appealed to soldiers and security forces to defect, and assured demonstrators that “American help is on the way.” It also comes against the backdrop of Trump’s own rhetoric encouraging protestors to “take over your institutions” and warning Tehran of “very strong action” if executions of demonstrators proceed.

History and current status

From fallen throne to floating mandate: Pahlavi’s long exile and fragile comeback

Reza Pahlavi is the eldest son of Mohammad Reza Shah, overthrown in the 1979 Islamic Revolution. He has lived in exile in the United States for nearly half a century and has long been a polarizing figure in Iranian politics: to some, he represents continuity of the pre‑revolutionary state; to others, he is an emblem of dictatorship and foreign alignment.

For much of the post‑revolutionary period, US policy makers treated Pahlavi as marginal to serious Iran strategy. Even during earlier protest waves, Washington was cautious about overt engagement, wary that any visible US–Pahlavi axis would validate regime narratives of foreign-orchestrated unrest and further endanger demonstrators. Trump himself had, until recently, declined to meet Pahlavi and publicly signalled scepticism about his political relevance.

The latest protests, however, have altered this calculus. Reports from inside Iran describe chants of Pahlavi’s name at demonstrations in multiple cities, and polling by Ammar Maleki and others indicates that roughly one-third of Iranians express support for him while another third strongly oppose him, with the remainder undecided. This is a remarkably high level of name recognition and relative support compared to other fragmented opposition figures.

Concurrently, Pahlavi has invested substantial political capital in rebranding himself. He speaks less of restoring monarchy and more of shepherding a time‑bound transition to a democratic republic through a referendum and a constitutional conference of Iranian representatives. He has even circulated a “hundred‑day” plan for a transitional government, emphasising that “it is not about restoring the past.”

Key developments

Several developments over the past weeks and months are essential to understanding US thinking around Pahlavi’s role.

First, the protests that erupted in late December quickly spread to nearly 200 cities, combining socioeconomic grievances with explicit anti‑regime slogans.

Security forces responded with live fire, mass arrests, and an aggressive information blackout; casualty estimates range from roughly two thousand confirmed deaths to higher figures shared privately by foreign governments.

Second, Pahlavi has moved from the periphery of the conversation to its centre. He has used satellite channels, social media, and appearances on Western television to call for sustained civil resistance, frame the struggle as one of national liberation, and present himself as a secular, democratic alternative to the Islamic Republic.

In his recent statements, he has urged the regular army to abandon the regime and join the people, and he has called on diaspora Iranians to symbolically reclaim embassies by raising the pre‑revolutionary flag.

Third, Trump administration rhetoric has shifted from generic condemnation to increasingly explicit promises of support. The president has told Iranians that “help is on the way,” cancelled meetings with Iranian officials, and warned that the United States is prepared to take “very strong action” if executions of protesters proceed.

At the same time, key officials such as Secretary of State Marco Rubio have stressed that non‑military options remain under active consideration, including sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and support for the protest movement short of direct intervention.

Fourth, there is now a dual‑track engagement with Tehran and with Pahlavi. Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi has, according to multiple reports, used back channels to communicate with Witkoff, exploring the possibility of de‑escalation and negotiating over both the protests and the nuclear file.

In parallel, Witkoff’s secret in‑person meeting with Pahlavi has given the crown prince his first direct channel into the White House at the level of a designated envoy.

Latest facts and concerns

High stakes, thin ice: the hard limits of a Pahlavi‑centric strategy

Several facts constrain any US “plan” involving Reza Pahlavi and generate serious policy concerns in Washington and among regional allies.

The first is the opposition’s fragmentation. The Iranian anti‑regime landscape includes monarchists, republicans, leftists, ethnic and religious minorities, and figures across the secular–religious spectrum. Analysts and think tanks have repeatedly warned that there is no unified leadership or coherent shadow government ready to step in.

Pahlavi’s support, while significant compared with others, remains far from hegemonic; for many Kurds, Baluchis, and other minorities, the prospect of a centralized monarchy in new clothing is deeply unattractive, and alternative visions such as federalism or decentralisation command strong loyalty.

The second is the risk of foreign‑intervention stigma. Tehran has long framed exiled opposition groups, especially monarchists, as tools of the United States, Israel, or the United Kingdom. Public US endorsement of Pahlavi as a “chosen” leader would hand the regime a powerful narrative weapon, potentially discrediting both him and the broader protest movement as foreign puppets.

The third is operational: installing or even facilitating the return of an exiled prince to oversee a transition in a country of nearly ninety million people would require an extraordinary degree of external intervention, ranging from military strikes to coercive diplomacy and economic warfare.

Military, legal, and intelligence assessments in Washington stress both the scale of the undertaking and the potential for unintended consequences, including civil war, regional escalation, and a consolidation of hardline elements such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Cause-and-effect analysis

Echoes and escalations: how one quiet meeting ripples through Tehran and Washington

At a strategic level, the Witkoff–Pahlavi contact can be seen as both a consequence and a cause of shifting US calculations. The cause lies in the protest movement’s durability and the unexpected resonance of Pahlavi’s name inside Iran.

US officials admit they were “surprised” to hear his name chanted spontaneously at demonstrations, and public‑opinion surveys corroborate that he commands a base of support unmatched by other opposition aspirants. That empirical reality has triggered a re‑evaluation: a figure once dismissed as a relic is now treated as a serious, if controversial, option in contingency planning.

The meeting is also a cause in its own right, altering expectations and incentives for multiple actors. For Pahlavi, White House access validates his claim that he is in “direct communication” with the Trump administration and that they “already know what we propose as an alternative, as a transition.” That, in turn, enables him to tell protestors that “help is on the way,” fusing their domestic struggle with a promise of external backing.

For the regime, the same development reinforces its perception that the protests are embedded in a broader external campaign to bring about regime change. Tehran’s messaging to domestic audiences, its warnings about “foreign mercenaries,” and its threats against US assets in the region all draw energy from any visible coordination between Washington and exiled opposition figures.

This increases the likelihood of harsh crackdowns, escalatory posturing in the Gulf, and efforts to exploit divisions among the opposition.

For Washington, the meeting deepens the commitment problem. The more visibly it flirts with Pahlavi as a transitional leader, the more it will be held responsible—by both Iranians and allies—if it ultimately declines to act when repression intensifies. Yet acting too decisively on Pahlavi’s behalf risks not only military escalation but also the delegitimisation of the very revolution it purports to support. Thus, the contact creates a feedback loop in which symbolic alignment raises expectations faster than the United States can credibly meet them.

Future steps

Playing the Pahlavi card: four ways the US could move without committing

Given these constraints, the likely US approach over the coming months will be cautious, layered, and deliberately ambiguous. In practical terms, this means four broad lines of effort.

First, continued exploratory engagement with Pahlavi and other opposition actors. Witkoff and other officials are likely to use private meetings to map the spectrum of opposition demands, test Pahlavi’s readiness to work within a pluralistic coalition, and pressure him to frame his role in strictly transitional and democratic terms rather than dynastic restoration.

Second, integration of Pahlavi into information and psychological operations without formal anointment. US statements will probably continue to emphasise Iranians’ right to self‑determination while amplifying messages that emphasize unity, non‑sectarianism, and the possibility of a post‑Islamic Republic political order.

Pahlavi’s speeches and calls for defections from the army may be quietly signal‑boosted through sympathetic media, but official US documents are unlikely in the near term to designate him the “leader” of the Iranian people.

Third, parallel pressure and negotiation tracks with Tehran. Back‑channel contacts such as those between Araghchi and Witkoff will persist, seeking to trade de‑escalation and limited concessions for restraint in the crackdown, nuclear transparency, or regional behaviour.

Pahlavi’s mere existence as a credible alternative leader will serve as an implicit bargaining chip: the worse the regime behaves, the more seriously Washington can threaten to empower him.

Fourth, contingency planning for extreme scenarios. Within the US national security bureaucracy, the current moment will accelerate planning for contingencies such as sudden regime collapse, coup attempts, or mass defections. In those plans, Pahlavi may be scripted as one of several possible civilian figures to front a transitional authority, with heavy emphasis on convening a broad constitutional assembly and a referendum rather than restoring a simple monarchy.

Conclusion

No coronation, only contingency: why the future of Iran still lies in Iranian hands

There is no secret, fully articulated US blueprint to “put the Shah’s son back on the Peacock Throne.”

The available evidence instead points to something more fluid and more characteristic of contemporary US foreign policy: a hedged posture that simultaneously courts an exiled prince, keeps diplomatic channels open to the regime he seeks to replace, and bets heavily on the agency of Iranians themselves to determine whether Pahlavi is an asset, an obstacle, or an irrelevance.

In that posture, the “plan for Prince Reza” is less a discrete project than a conditional option—a card Washington is willing to keep in its hand, especially as protests radicalise and casualties mount, but not yet one it is prepared to slam on the table at the risk of regional war and domestic backlash.

Whether that calculus shifts will depend less on the eloquence of Pahlavi’s appeals or the secrecy of Witkoff’s meetings than on the evolution of power inside Iran: the behaviour of the IRGC, the cohesion of the ruling elite, and the capacity of ordinary Iranians to sustain a revolutionary movement under conditions of brutal repression and international ambiguity.