The prince in the toolbox: Reza Pahlavi and America’s reversible bet on Iran’s future

Summary

The sudden elevation of Reza Pahlavi from a largely ceremonial exile to a man discreetly courted by the White House encapsulates the opportunistic pragmatism of current US policy toward Iran.

Washington has not discovered a new ideological love for monarchy, nor has it drafted a restoration script in the style of twentieth‑century coups. Instead, the Trump administration appears to be folding Pahlavi into a broader repertoire of pressure tools and contingency options, treating him less as a destined sovereign than as a movable piece on a volatile chessboard.

The catalyst for this reappraisal is not romance but arithmetic. Protesters in city after city are reported to chant Pahlavi’s name, not out of nostalgia for the secret police and crony capitalism of the 1970s, but because he represents, for a significant minority, a familiar symbol of a non‑theocratic state.

Polling that attributes roughly one‑third support to him—offset by roughly one‑third active opposition—tells US officials two things at once: no other exile commands comparable recognition, and any attempt to anoint him as the sole leader would be deeply divisive.

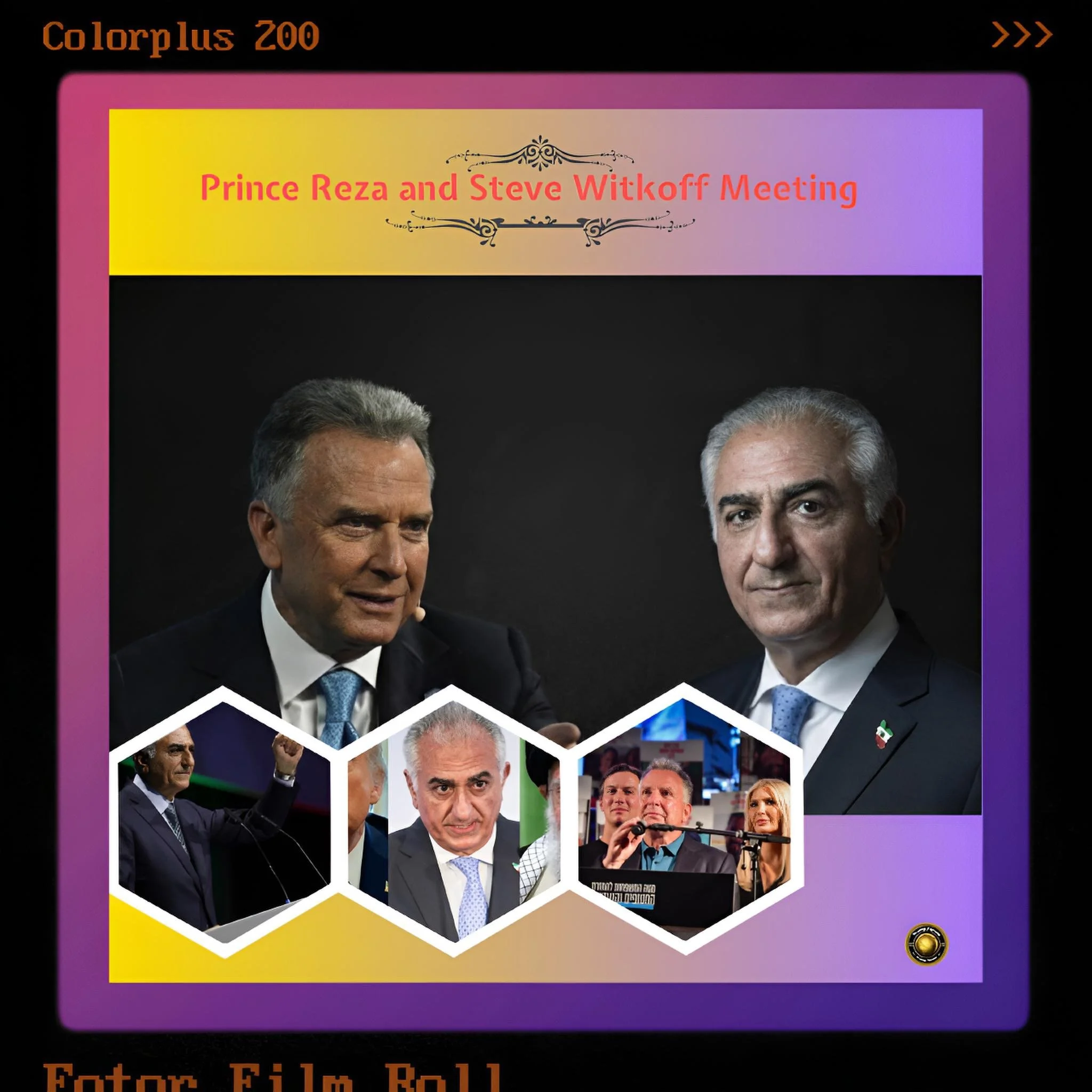

The Witkoff–Pahlavi encounter, held in secret over a Washington weekend, must be read against that ambiguous backdrop. Pahlavi comes to the table as a man with a carefully rehearsed script: a hundred‑day transition plan, a promise of a referendum, a pledge that he seeks not to “restore the past” but to midwife a democratic future.

Witkoff, for his part, arrives not as a romantic monarchist but as an envoy tasked with synthesizing three pressures on the administration: a domestic political base that cheers muscular talk of regime change, a protest wave that begs for moral and material support, and an intelligence community that warns of the perils of owning Iran’s next revolution.

What emerges from that meeting, if one connects scattered public hints, is not a coronation but a conditional alignment.

Pahlavi gains what he craves most: recognition that he is no longer a lonely voice shouting into satellite channels but an interlocutor taken seriously by an American administration that has rediscovered the language of regime pressure. He can now credibly claim, as he has in recent interviews, that he is in “direct communication” with the White House and that his transition blueprint is understood at the highest levels.

The United States, in turn, gains a flexible instrument whose value is almost entirely situational. In a low‑escalation scenario, in which protests ebb under repression, and the regime regains its footing, Pahlavi remains useful primarily as a moral and rhetorical figure: a reminder that an alternative Iran exists in the imagination of millions and a symbol to which the diaspora can attach its lobbying and advocacy. Washington can meet with him, quote him, and host him without committing itself to onerous security obligations.

In a high‑escalation scenario, by contrast, his role could expand dramatically. If the regime were to fracture—if the IRGC splintered, if the supreme leader died without a managed succession, if the regular army refused orders to fire on protesters—there would be an urgent demand for some form of civilian anchor to stabilize a transition.

Pahlavi’s pedigree, his long‑standing relationships in Western capitals, and his own declared preference for a narrow, time‑bound transitional mandate would make him a tempting candidate to front a provisional authority or a constitutional conference.

That does not, however, mean that the United States is quietly plotting a “Pahlavi option” in isolation from other variables.

On the contrary, serious analysts in and around government stress that any externally blessed transition figure must be nested inside a broad coalition that includes republicans, ethnic and religious minorities, women’s rights activists, labour organisers, and elements of the technocratic elite willing to break with the Islamic Republic.

One of the hard lessons of the past two decades—from Baghdad to Kabul—is that over‑investment in a single charismatic exile can produce hollow states and brutal backlashes.

An additional complication is the narrative. The Islamic Republic’s legitimacy has always rested partly on its claim to have expelled foreign domination and royal decadence. Tehran’s hardliners would welcome nothing more than a US–Pahlavi embrace as proof that the protests are a foreign plot to “reinstall the Shah.”

Any visible American attempt to choreograph Pahlavi’s return risks toxifying him among precisely the constituencies—workers, minorities, pious urbanites—whose participation would be essential to a sustainable democratic transition.

For that reason, the emerging US strategy seems to rely on calibrated ambiguity. Trump can tell Iranians that “help is on the way” without specifying whether that help will be airstrikes, sanctions, technology, or simply words.

Pahlavi can tell his compatriots that the administration “knows our alternative” without explicitly pledging to make him president. Witkoff can listen to both Araghchi and Pahlavi in the same week, signalling to each that the United States has options other than the other side’s survival.

This ambiguity serves Washington’s interest in one more respect: it keeps the burden of agency on the Iranians themselves.

If protests subside, if security forces hold, and if the regime weathers the storm, US officials can say with some justification that they respected the limits of external influence and avoided plunging the region into another catastrophic war.

If, however, the regime implodes under its own contradictions, Washington can argue that it merely helped midwife an outcome Iranians themselves brought about—while being ready to lean on a pre‑vetted, internationally legible figure like Pahlavi to prevent chaos.

The cost of this approach is moral and psychological. Protesters inside Iran are not abstract variables; they are human beings who read the duplicate headlines and social‑media posts that Western audiences do. When they hear both their exiled prince and the president of the United States talk in the register of imminent assistance, they may reasonably infer that the world is preparing to act.

If that assistance never materializes beyond sanctions and statements, the resulting sense of abandonment could deepen cynicism toward both Pahlavi and the United States, poisoning the well for future cooperation.

In this sense, the “plan” for Prince Reza is less about him than about how Washington manages expectations. The administration is trying to square an impossible circle: to keep Pahlavi close enough that he is usable if history turns, but distant enough that his association does not prematurely deform the uprising or drag America into a war it does not want.

That is not a strategy designed to satisfy either monarchists dreaming of a triumphant return or anti‑imperialists warning of an impending palace coup. It is a strategy designed to keep options open in a landscape where every choice carries intolerable risks and no actor—not Trump, not Pahlavi, not the clerical establishment—fully controls the script.