July 11, 1995: The Srebrenica Genocide - 30 Years On - The promise of Never again

Introduction

On July 11, 1995, the town of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina became the site of Europe’s worst atrocity since World War II.

Today marks the 30th anniversary of the genocide that claimed the lives of 8,372 Bosnian Muslim men and boys, representing not just a single act of violence but the culmination of a systematic campaign of ethnic cleansing driven by radical Serbian nationalism and the ideology of “Greater Serbia.”

The Path to Genocide

Historical Context and Yugoslav Disintegration

The Srebrenica genocide did not occur in isolation but was the horrific climax of a carefully orchestrated campaign that began decades earlier.

The roots of the tragedy can be traced back to the death of Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980, which unleashed long-suppressed ethnic tensions within the socialist federation.

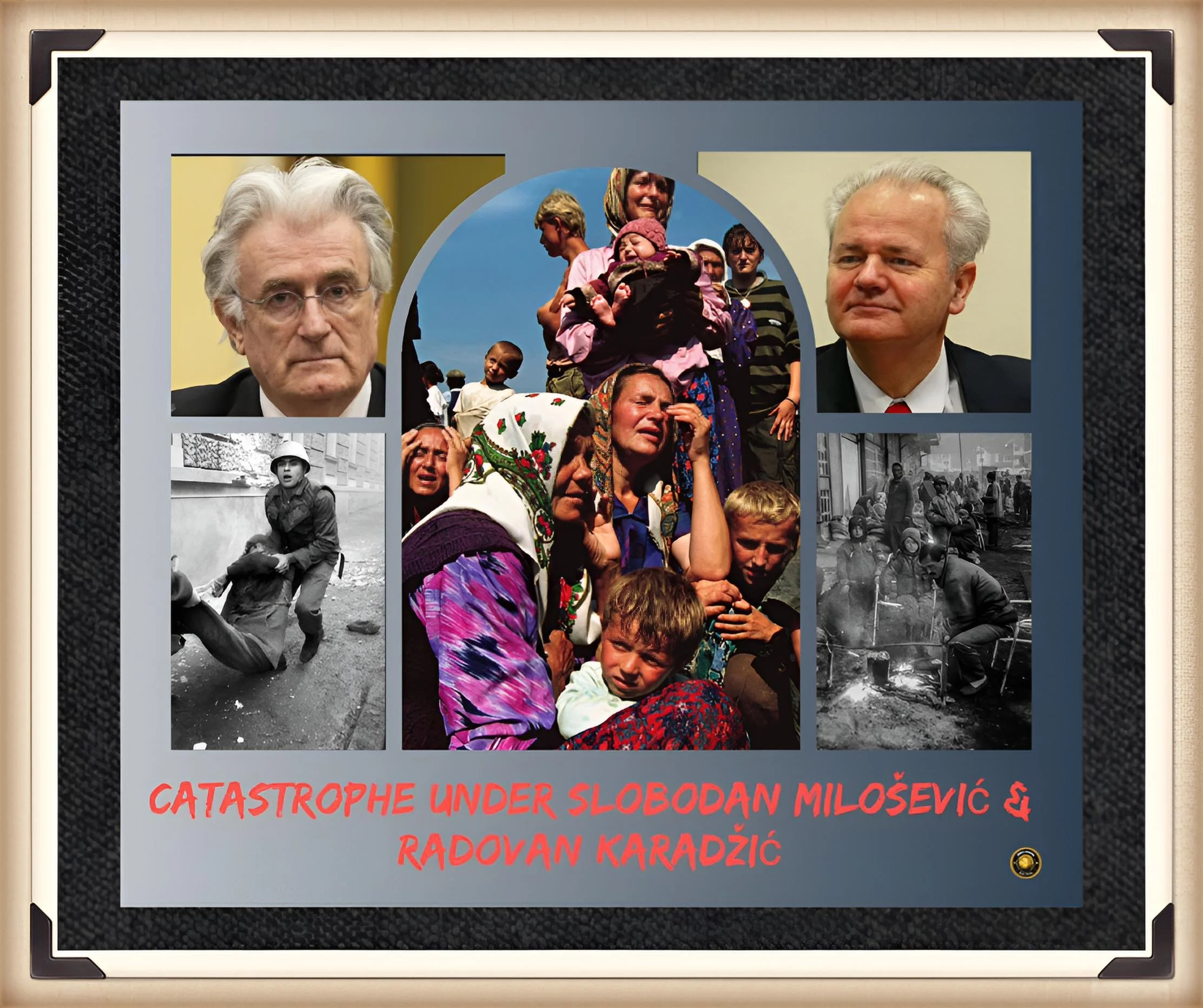

Following Tito’s death, the rise of Serbian nationalism under Slobodan Milošević fundamentally transformed the political landscape of Yugoslavia.

Milošević, who became president of Serbia in 1989, actively promoted the “Greater Serbia” concept - an expansionist ideology that sought to unite all Serbian-populated territories under one state.

This vision required systematically removing non-Serbian populations from coveted territories, particularly Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Greater Serbian ideology was not merely territorial but deeply rooted in ethnic supremacist thinking.

As documented by scholars, this nationalism portrayed Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) and Croats as obstacles to Serbian historical destiny.

The ideology drew upon a distorted interpretation of medieval Serbian history, particularly the 1389 Battle of Kosovo, which became a rallying cry for Serbian nationalism and territorial expansion.

The Bosnian War and Ethnic Cleansing Campaign

When Bosnia and Herzegovina declared independence on March 3, 1992, following a referendum in which 99.7% of voters supported independence, the stage was set for systematic ethnic cleansing.

The Bosnian Serbs, led by Radovan Karadžić and supported by Belgrade, immediately rejected the referendum results and launched a military campaign to carve out ethnically pure Serbian territories.

The ethnic cleansing campaign was comprehensive and systematic, involving “killing of civilians, rape, torture, destruction of civilian, public, and cultural property, looting and pillaging, and the forcible relocation of civilian populations”.

The United Nations Security Council noted that while all sides committed violations, there was “no factual basis for arguing that there is a ‘moral equivalence’ between the warring factions,” with Serb forces being responsible for the vast majority of systematic ethnic cleansing.

By mid-1992, the campaign had displaced approximately 2.7 million people, making it the largest exodus in Europe since World War II.

The methods employed were deliberate and calculated, designed not just to remove populations but to ensure they could never return by destroying their cultural and religious heritage.

The Srebrenica “Safe Area” and International Failure

In April 1993, the UN Security Council designated Srebrenica as a “safe area” under Resolution 819, promising to protect the civilian population. However, this designation proved to be a fatal illusion.

The UN peacekeeping contingent consisted of only 400 lightly armed Dutch soldiers, completely inadequate to defend against the well-equipped Bosnian Serb forces.

The international community’s failure was not merely due to insufficient resources but also to political will.

As UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan later acknowledged in a critical 1999 review: “Through error, misjudgment and an inability to recognize the scope of the evil confronting us, we failed to do our part to help save the people of Srebrenica from the Bosnian Serb campaign of mass murder”.

The Genocide Unfolds: July 11-16, 1995

The final assault on Srebrenica began on July 6, 1995, with Operation Krivaja 95.

By July 11, Bosnian Serb forces under General Ratko Mladić had overrun the town. In a chilling statement recorded on film, Mladić declared: “We give this town to the Serb nation…The time has come to take revenge on the Muslims”.

The systematic nature of the genocide was evident in its execution. Men and boys were separated from women and children, with the latter being forcibly expelled on buses while the former were detained in various locations.

The killing began on July 12 and continued through July 16, with mass executions taking place at multiple sites, including schools, warehouses, and fields.

The genocide was not limited to murder but included widespread sexual violence, with testimonies documenting systematic rape and torture.

The perpetrators also attempted to cover up their crimes by moving bodies between mass graves using heavy machinery, scattering remains across multiple sites to impede identification.

The Architects of Genocide

The highest levels of Bosnian Serb leadership orchestrated the Srebrenica genocide.

Radovan Karadžić, the president of Republika Srpska, was the political mastermind who issued Directive 7 in March 1995, ordering his forces to “create an unbearable situation of total insecurity with no hope of further survival or life for the inhabitants of Srebrenica”.

General Ratko Mladić, commander of the Bosnian Serb Army, directly oversaw the military operation and the subsequent massacre.

Both men were later convicted of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY).

The genocide was not the work of rogue elements but represented the systematic implementation of an official policy of ethnic cleansing.

As the ICTY determined, the killings were part of a broader joint criminal enterprise aimed at permanently removing Bosnian Muslims and Croats from Serb-claimed territory.

International Justice and Recognition

The international legal response to Srebrenica has been groundbreaking. The ICTY, established in 1993, conducted extensive investigations and trials that resulted in multiple convictions for genocide.

The International Court of Justice also ruled in 2007 that the Srebrenica massacre constituted genocide.

In May 2024, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 78/282, designating July 11 as the International Day of Reflection and Commemoration of the 1995 Genocide in Srebrenica.

The resolution passed with 84 countries in favor, 19 against, and 68 abstentions, demonstrating continued divisions over the genocide’s recognition.

Genocide Denial and Contemporary Threats

Despite overwhelming evidence and legal rulings, genocide denial has become official state policy in both Serbia and Republika Srpska. Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and Republika Srpska President Milorad Dodik have systematically promoted denial, with Dodik calling the genocide “a fabricated myth”.

This denial is not merely historical revisionism but an active political strategy. Dodik has embedded genocide denial into educational curricula, glorified war criminals by naming public spaces after them, and used denial as a tool for separatist politics.

The denial campaign has been supported by commissioned reports, such as the controversial Greiff report, which attempted to challenge established legal facts about the genocide.

The New Generation and Memory

Thirty years after the genocide, a new generation of Bosnians has grown up with its legacy.

In Srebrenica today, children of different ethnic backgrounds attend school together, yet they carry the burden of intergenerational trauma and divided historical narratives.

Educational systems remain deeply divided, with some schools operating “under one roof” - physically separating students by ethnicity and teaching different curricula.

In Republika Srpska, the genocide was omitted from school curricula until 2018, and even now, students learn competing versions of history depending on their ethnic background.

Young people like Nia Abadžić, a university student in Sarajevo, reflect on how “war traumas that my generation did not experience first-hand can still shape young minds, depending on how they are passed down to us”.

This highlights the ongoing challenge of breaking cycles of inherited trauma and division.

International Perspective and Global Commemoration

The international community’s response to the 30th anniversary demonstrates progress and persistent challenges.

Following the UN resolution, at least ten countries are officially commemorating the genocide this year. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen described Srebrenica as “among the darkest chapters in Europe’s collective memory”.

However, significant gaps remain. The vote on the UN resolution revealed deep divisions, with major powers like Russia and China voting against it, while many countries abstained.

This reflects broader geopolitical tensions and the selective application of international justice.

Luigi Soreca, Head of the EU Delegation to Bosnia and Herzegovina, emphasized that “there is no place for genocide denial, historical revisionism or the glorification of war criminals in societies that value truth and justice”.

Yet the persistence of such denial, particularly in the context of ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, demonstrates the fragility of international commitment to preventing genocide.

Lessons and Contemporary Relevance

The Srebrenica genocide offers crucial lessons for genocide prevention that remain tragically relevant today.

As noted by scholars and survivors, the warning signs were present but ignored by the international community. Civil society organizations and UN Special Rapporteurs raised alarms about the impending catastrophe, but their warnings were brushed aside.

The genocide also demonstrates how political leaders can weaponize extremist ideologies to justify mass atrocities.

The Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences’ 1986 Memorandum provided intellectual justification for Greater Serbian nationalism, while political leaders like Milošević and Karadžić transformed these ideas into genocidal policies.

Perhaps most importantly, Srebrenica shows how genocide denial can become a tool for ongoing oppression and potential future violence.

As Justice Info notes, “denial of the Srebrenica genocide is intensifying” and “has hardened into official state policy” in Serbia and Republika Srpska.

The Path Forward

As Bosnia and Herzegovina marks this somber anniversary, the country remains divided between those who remember and deny.

The Srebrenica Memorial Centre continues its vital work of preserving memory and educating new generations, having formed partnerships with Holocaust memorial institutions worldwide to protect historical facts from revisionist attacks.

The challenges are immense. Milorad Dodik continues to threaten secession of Republika Srpska, using genocide denial as a political weapon.

His threats have intensified following his recent legal troubles, including a conviction for defying international authority and an outstanding arrest warrant.

Yet there are also signs of hope. Organizations like the “House of Good Tones” music school in Srebrenica bring together children of all ethnicities, showing that reconciliation is possible.

Survivors like Almasa Salihovic, now a spokesperson for the Srebrenica Memorial Centre, continue to share their stories to ensure the genocide is never forgotten.

The 30th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide serves as both a commemoration of the victims and an urgent reminder of the work that remains.

As survivor Munira Subašić, president of the Mothers of Srebrenica, told the UN General Assembly: “When you kill a mother’s child, you have killed a part of her”. The pain of loss endures, but so does the determination to ensure that such horrors never happen again.

The promise of “Never Again” can only be fulfilled through continued vigilance, education, and the unwavering commitment to truth and justice.

As the international community faces new threats of genocide and ethnic cleansing around the world, the lessons of Srebrenica remain as relevant and urgent as ever.