The 1969 Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: How the World’s Closest Nuclear Powers Nearly Triggered World War III

Introduction

The 1969 Sino-Soviet border conflict represents arguably the most dangerous nuclear crisis of the Cold War era, bringing two nuclear-armed communist superpowers to the brink of atomic warfare over a small, strategically insignificant river island.

This seven-month undeclared military conflict between the Soviet Union and China escalated from localized border skirmishes to serious consideration of nuclear first strikes, requiring unprecedented American diplomatic intervention to prevent a global catastrophe.

FAF, Defense.Forum analyzes the crisis demonstrated how ideological splits between former allies could rapidly escalate beyond conventional warfare, with both sides placing their nuclear forces on high alert and Soviet leadership actively contemplating preemptive strikes against Chinese nuclear facilities.

The conflict’s resolution ultimately reshaped Cold War geopolitics, accelerating Sino-American rapprochement and fundamentally altering the strategic balance that had defined the post-World War II era.

Historical Context and Rising Tensions

The roots of the 1969 border conflict stretched back decades to what China considered “unequal treaties” imposed by Tsarist Russia during the Qing Dynasty’s period of weakness.

The 1860 Treaty of Peking established the Ussuri River as the boundary between Chinese and Russian territory.

Still, by the 1960s, Chinese leaders under Mao Zedong began challenging these historical arrangements as illegitimate.

The Chinese government argued that over 600 of the river’s 700 islands, including the strategically located Zhenbao Island (known to the Soviets as Damansky Island), rightfully belonged to China based on the international legal principle that river boundaries should follow the main channel’s center line.

The immediate context for the 1969 crisis emerged from the broader Sino-Soviet split developing since the late 1950s.

By 1964, both sides had begun dramatically increasing their military presence along the 4,000-mile border, transforming what had once been a peaceful frontier into one of the world’s most heavily militarized boundaries.

The situation deteriorated further following the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 and the subsequent announcement of the Brezhnev Doctrine, which asserted Moscow’s right to intervene militarily in any socialist country deemed to be deviating from orthodox communist principles.

Chinese leaders interpreted this doctrine as directly threatening their sovereignty, particularly given ongoing ideological disputes over Mao’s interpretation of Marxism-Leninism versus Soviet “revisionism.”

The Cultural Revolution’s domestic dynamics also played a crucial role in escalating tensions. Mao Zedong actively promoted an anti-Soviet campaign that portrayed the USSR as a “social imperialist” power no different from the United States.

This ideological assault served multiple domestic purposes: it helped consolidate Mao’s authority during internal party turmoil, provided a unifying external enemy to rally Chinese nationalism, and offered an opportunity to demonstrate China’s independence from both superpowers.

The March 2 Zhenbao Island Incident

The catalyst for the 1969 crisis came on the morning of March 2, when what appeared to be a routine border patrol encounter escalated into the deadliest Sino-Soviet confrontation since the end of World War II.

According to Soviet accounts, approximately 30 Chinese soldiers were observed crossing the frozen Ussuri River toward Zhenbao Island, prompting Soviet Border Guard Senior Lieutenant Ivan Strelnikov to lead a patrol of border guards to intercept them.

This encounter had become commonplace along the disputed border, typically resulting in verbal confrontations and demands that the opposing side withdraw from contested territory.

However, this incident fundamentally differed from previous encounters because it represented a carefully planned Chinese ambush rather than a spontaneous confrontation.

Soviet investigations later revealed that approximately 300 Chinese soldiers had infiltrated the island under cover of darkness on March 1, positioning themselves in concealed positions throughout the island’s terrain.

When the Soviet patrol approached the visible Chinese contingent on the morning of March 2, the first line of Chinese soldiers suddenly scattered, revealing a second line of troops who immediately opened fire on the exposed Soviet forces.

The resulting firefight lasted several hours and involved mortars, artillery, and anti-tank weapons from both sides. The Soviet casualties were devastating: 31 border guards were killed on March 2 alone, including Senior Lieutenant Strelnikov, with 14 additional personnel wounded.

The Chinese forces, benefiting from their prepared positions and numerical superiority, inflicted these casualties before withdrawing to their side of the border.

Soviet forces claimed to have killed over 200 Chinese soldiers, though more accurate estimates based on Chinese cemetery records suggest approximately 20-21 Chinese fatalities on March 2.

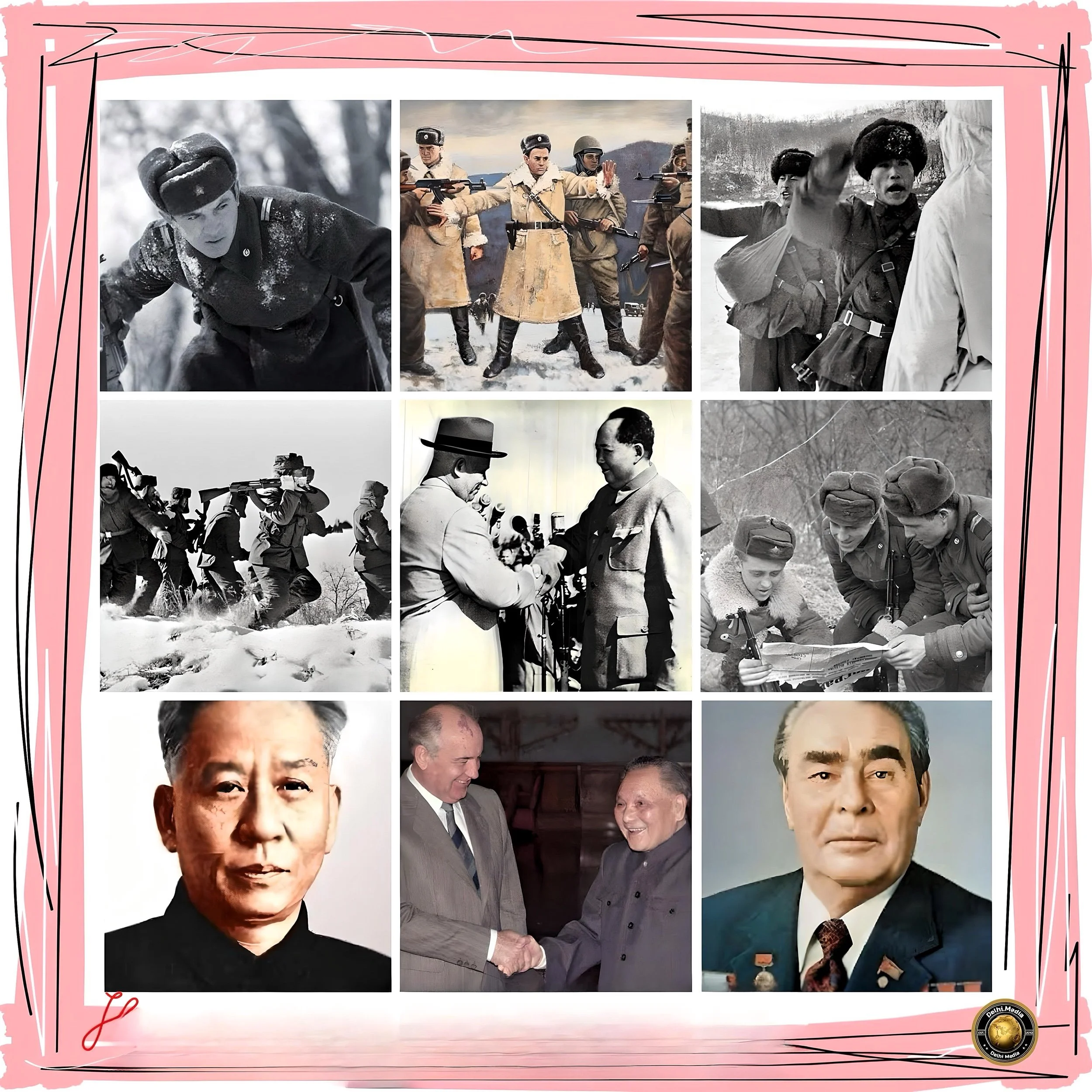

Escalation and the March 15 Battle

The March 2 incident was only the beginning of an escalating series of confrontations that would bring the world closer to nuclear war than any previous Cold War crisis.

The Soviet leadership, stunned by what they perceived as unprecedented Chinese aggression, began planning a massive retaliation.

On March 15, a much larger and more destructive battle erupted when Chinese forces moved as many as 2,000 troops onto Zhenbao Island to confront approximately equal numbers of Soviet forces.

The March 15 engagement represented a significant escalation in both scale and intensity. Soviet forces employed heavy artillery, including massive barrages that Chinese observers later described through loudspeakers, calling out the names of specific Soviet commanders and pleading for them to cease fire.

The battle resulted in 24 additional Soviet casualties (both border guards and regular army personnel), while Chinese losses, though officially stated at only 12 men, were likely much higher based on testimony from later Chinese defectors who claimed “several hundred bodies” were secretly buried in mass graves.

The psychological impact of these confrontations on Soviet leadership cannot be overstated.

As one Russian specialist noted, “It was a surprise to Moscow… none of the border provocations had ever approached a military clash. We did not expect a conflict and were entirely unprepared for a serious one”.

The Soviets had grown accustomed to routine border incidents that were resolved through diplomatic protests rather than armed confrontation, making the Chinese willingness to shed blood particularly shocking to Moscow’s leadership.

Nuclear Escalation and Global Crisis

The most dangerous phase of the crisis began in the summer of 1969 when Soviet frustration with Chinese intransigence led to serious consideration of nuclear options.

Moscow adopted what military analysts would later term a “coercive diplomacy strategy,” combining repeated negotiation proposals with increasingly provocative threats of nuclear escalation.

Soviet leaders calculated that the threat of nuclear attack would force Beijing to enter serious negotiations about border demarcation and broader Sino-Soviet relations.

The nuclear dimension of the crisis reached its most alarming point in August 1969, when Soviet officials began conducting what amounted to a diplomatic reconnaissance mission regarding international reaction to a potential nuclear strike against China.

On August 20, Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin met with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to gauge American reactions to a hypothetical Soviet attack on Chinese nuclear facilities.

This extraordinary diplomatic démarche represented one of the most dangerous moments in Cold War history, as it indicated serious Soviet consideration of preemptive nuclear action against China’s nascent nuclear program.

Chinese leadership recognized the gravity of the Soviet nuclear threats and responded with unprecedented mobilization measures.

In October 1969, Chinese leaders implemented what amounted to a national preparation for nuclear war: Mao Zedong relocated to Wuhan, Defense Minister Lin Biao moved to Suzhou, and the general staff transferred to nuclear-proof bunkers in the Western Hills outside Beijing.

The Chinese military scattered 940,000 soldiers, 4,000 aircraft, and 600 naval vessels from their regular bases while central archives were evacuated from Beijing to southwestern China.

This represents the first and only time in history that China placed its nuclear forces on full alert status.

American Intervention and Crisis Resolution

The resolution of the nuclear crisis required unprecedented American diplomatic intervention that fundamentally altered Cold War dynamics.

When Nixon administration officials learned of Soviet nuclear contingency planning against China, they made a calculated decision to prevent what could have become a catastrophic escalation

According to Chinese state media accounts, Henry Kissinger delivered an ultimatum to Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin, stating that “as soon as the Soviets set off their first missile against China, the US will launch nuclear missiles at 130 Soviet cities”.

This American intervention represented a remarkable strategic reversal, given that the United States and China remained technically enemies with no formal diplomatic relations.

However, Nixon and Kissinger recognized that a Soviet nuclear attack on China would fundamentally alter the global strategic balance in Moscow’s favor, potentially making the Soviet Union the world’s unchallenged superpower.

The American nuclear threat proved credible enough to deter Soviet action, demonstrating how the triangular dynamic between the three powers had already begun reshaping Cold War calculations.

The immediate crisis began de-escalating in September 1969 when Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin met with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai at Beijing Airport.

This hastily arranged meeting, requested by the Soviet side, focused primarily on the urgent need to prevent further military escalation along the border.

Zhou Enlai emphasized that while ideological debates between the two countries might continue indefinitely, they should not lead to armed conflict or affect normal state-to-state relations.

Both leaders agreed to provisional measures to maintain the status quo along the border and disengage military forces in disputed areas.

Long-term Consequences and Strategic Realignment

The 1969 Sino-Soviet border conflict produced far-reaching consequences that extended well beyond the immediate resolution of border tensions.

Most significantly, the crisis accelerated the process of Sino-American rapprochement that would culminate in Nixon’s historic 1972 visit to China.

Chinese leaders, having experienced firsthand the credibility of Soviet nuclear threats, recognized the strategic necessity of counterbalancing Soviet power through improved relations with the United States.

The border negotiations, which resumed in October 1969, proved to be protracted and largely unsuccessful for over two decades.

Despite periodic diplomatic contacts, serious progress on resolving the territorial disputes did not occur until 1991, coinciding with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The final resolution required a comprehensive agreement signed in 2003, followed by additional protocols in 2008 that conclusively settled all outstanding border issues between China and Russia.

The nuclear dimension of the crisis also had lasting implications for both countries’ strategic doctrines.

For China, the experience of Soviet nuclear coercion reinforced Mao’s determination to develop an independent nuclear deterrent capable of surviving a first strike.

For the Soviet Union, the crisis demonstrated the limitations of nuclear coercion against a determined adversary willing to accept significant risks rather than submit to pressure.

Assessment: The World’s Closest Approach to Nuclear War

Multiple factors support the argument that the 1969 Sino-Soviet crisis represented the world’s closest approach to nuclear warfare during the Cold War era.

Unlike the Cuban Missile Crisis, which involved careful diplomatic communication between Kennedy and Khrushchev throughout the crisis, the 1969 conflict featured minimal direct communication between Chinese and Soviet leaders for months after the initial fighting.

This lack of communication channels increased the risk of miscalculation and uncontrolled escalation.

The scope of military mobilization on both sides exceeded even what was seen during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

China’s decision to place its entire nuclear arsenal on high alert and evacuate major population centers represented preparations for actual nuclear warfare rather than diplomatic maneuvering.

Similarly, Soviet consideration of preemptive strikes against Chinese nuclear facilities indicated a willingness to cross the nuclear threshold that had not been seriously contemplated during previous Cold War crises.

The resolution of the crisis required direct American threats of nuclear retaliation against the Soviet Union, demonstrating how close the situation came to triggering a three-way atomic exchange.

Had the United States not intervened diplomatically and had Soviet leaders proceeded with planned strikes against Chinese nuclear facilities, the resulting Chinese retaliation against Soviet territory could have escalated into the global nuclear war that strategists had long feared.

Conclusion

The 1969 Sino-Soviet border conflict stands as a stark reminder of how quickly localized disputes between nuclear powers can escalate toward global catastrophe.

What began as competition over small river islands ultimately brought the world closer to nuclear war than any other Cold War crisis, requiring unprecedented diplomatic intervention to prevent catastrophic escalation.

The conflict demonstrated that ideological divisions between communist powers could prove just as dangerous as the East-West rivalry that dominated Cold War narratives.

The crisis also highlighted the crucial role of triangular diplomacy in preventing nuclear conflict.

American willingness to threaten nuclear retaliation against the Soviet Union to protect China represented a remarkable strategic calculation prioritizing global stability over ideological alignment.

This intervention prevented immediate nuclear escalation and set the stage for the strategic realignment that would define the final decades of the Cold War.

The lessons of 1969 remain relevant today, as rising tensions between nuclear-armed powers continue to pose risks of miscalculation and uncontrolled escalation in an increasingly multipolar world.