The Sino-Soviet Alliance and Subsequent Schism: Evolution from Cooperative Partnership to Escalating Hostility (1917-1991) culminating in a strong alliance by 2025.

Introduction

The evolution of Sino-Soviet relations represents one of the most dramatic reversals in 20th-century international relations. It transformed from a strategic alliance to a bitter rivalry that nearly precipitated nuclear war.

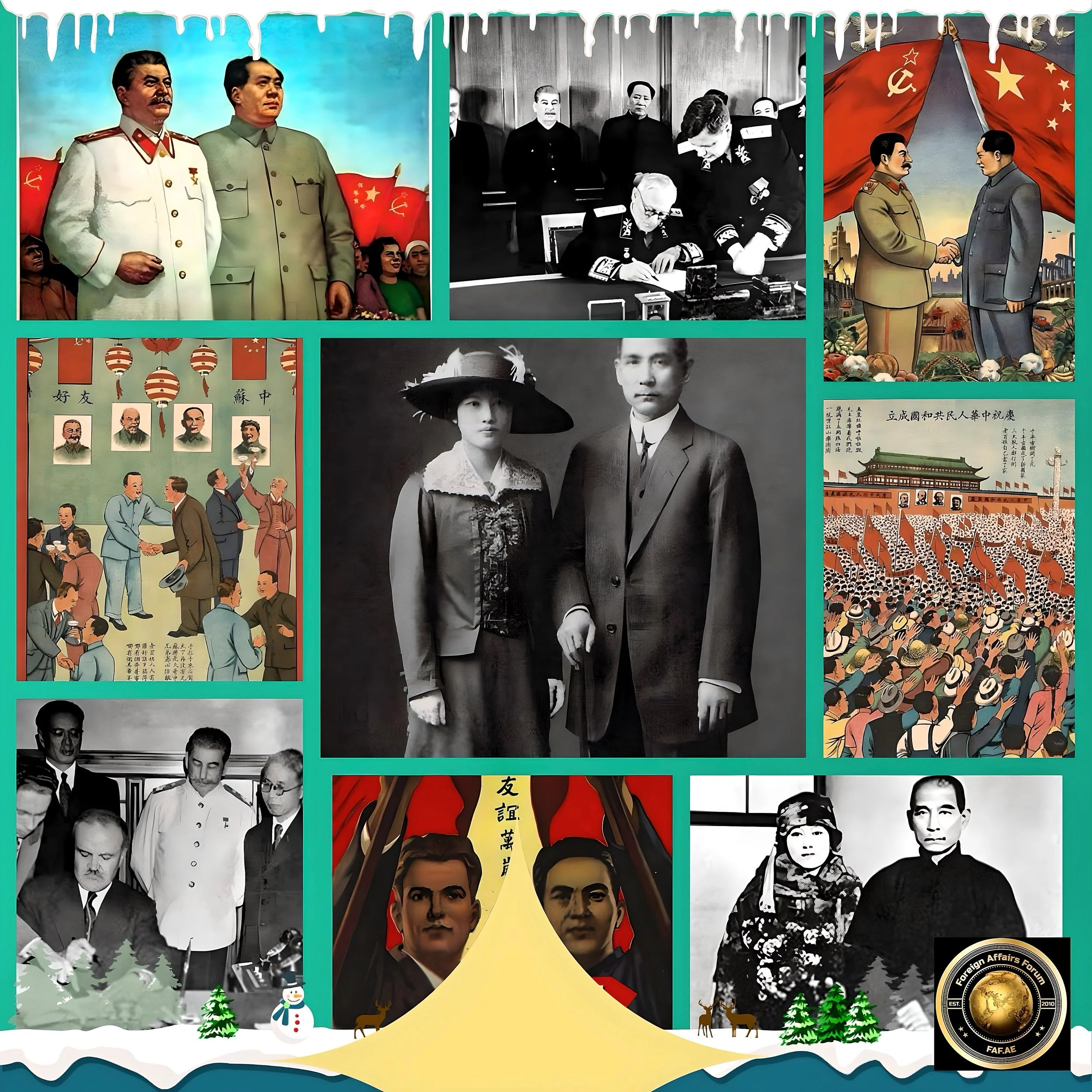

The relationship began with Soviet support for Chinese revolutionary movements in the 1920s. It culminated in a formal alliance in 1950, but it deteriorated rapidly due to ideological disputes, territorial conflicts, and competing claims to leadership of the global communist movement.

FAF. Imperialism.Forum analyzes the split between two great powers that fundamentally reshaped Cold War dynamics and ultimately contributed to China’s rapprochement with the United States. This demonstrates how ideological affinity alone cannot overcome geopolitical tensions and personal rivalries between communist leaders.

Early Soviet Involvement in Chinese Revolution (1917-1949)

Soviet Support for Multiple Chinese Factions

The Soviet Union’s involvement in Chinese affairs began almost immediately after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, reflecting Moscow’s strategic need for allies in its international isolation.

Contrary to expectations of consistent support for Chinese communists, Soviet policy toward China was remarkably pragmatic and often contradictory.

In 1921, Soviet Russia began supporting the Kuomintang (KMT), and by 1923, the Communist International instructed the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to sign a military treaty with the KMT.

This pragmatic approach reflected both Marxist orthodoxy, which held that feudal societies needed to develop capitalism before transitioning to socialism, and immediate geopolitical concerns about Japanese expansion in East Asia.

The establishment of Moscow Sun Yat-sen University in 1925 exemplified this dual approach to Chinese revolutionary politics. From 1925 to 1930, this Comintern institution served as a training camp for Chinese revolutionaries from the KMT and CCP, demonstrating Moscow’s hedging strategy.

The university was named after Sun Yat-sen, who contributed to the Chinese Revolution. Its curriculum focused on educating students in Marxism and Leninism while training cadres for both organizations.

This educational initiative reflected the Soviet Union’s belief that China needed unified revolutionary leadership to combat internal warlords and external imperialism.

The Complex Dynamics of Soviet Aid

The Soviet approach to China during the 1920s and 1930s was fundamentally shaped by strategic calculations rather than ideological purity.

Stalin thought the Chinese communists were “done for” and sought to secure an alliance with the Kuomintang as an anti-imperialist republican party, particularly because the Soviet Union was diplomatically isolated and needed allies.

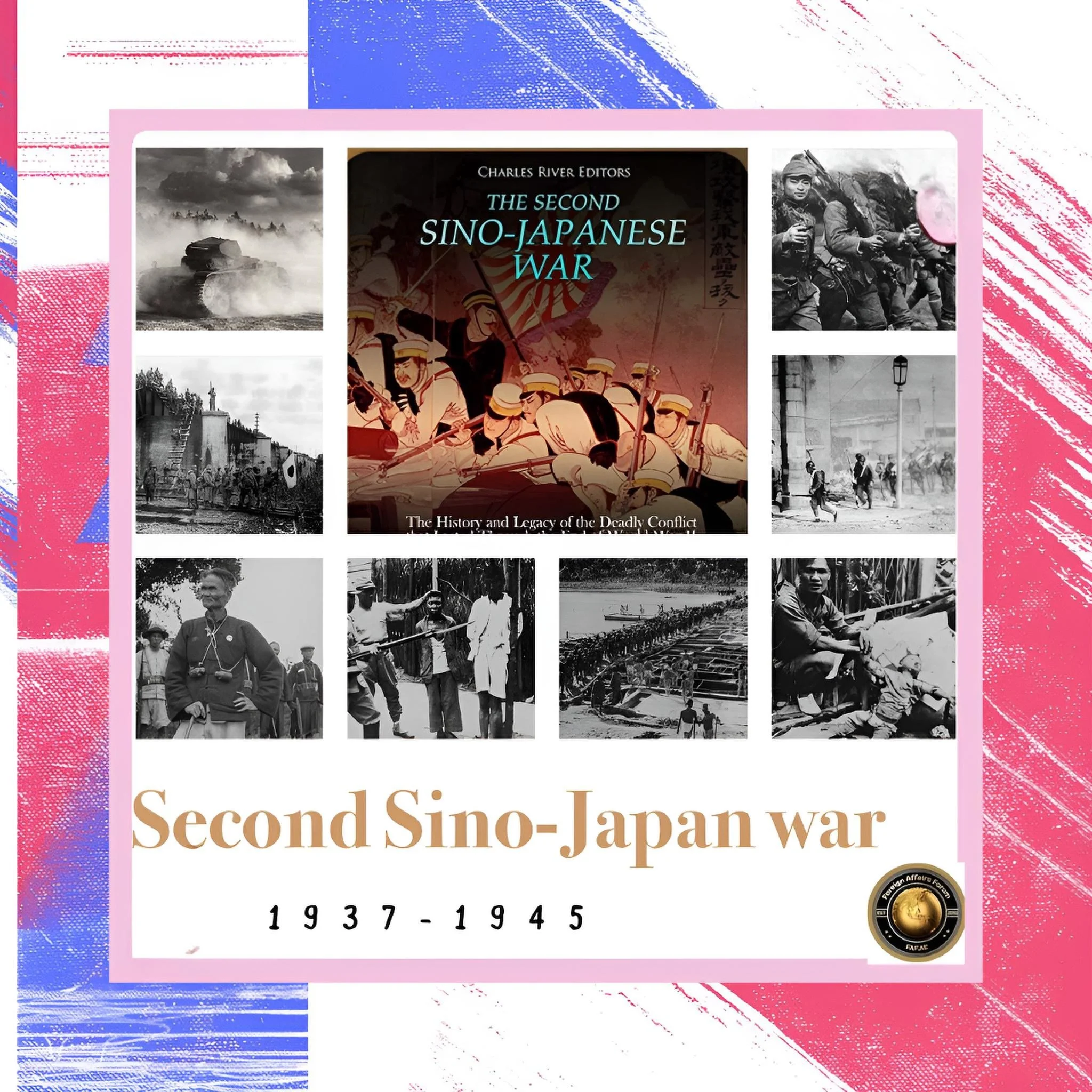

This pragmatic calculation proved prescient during the Second Sino-Japanese War when Soviet assistance to China became crucial for Chinese resistance.

The New China newspaper acknowledged in 1941, “Over the four years of our sacred war, the most critical and reliable foreign assistance has come from the Soviet Union. "

The KMT received most of this aid, while the CCP had to settle for more modest assistance.

Soviet military adviser Vasily Chuikov later explained the logic behind this seemingly contradictory policy: “The Communists would seem closer to us than Chiang Kai-shek… But this assistance would look like the export of revolution to a country with which diplomatic relations link us.

The CCP and the working class are still too weak to lead the struggle against the aggressor. “

This assessment reflected Moscow’s understanding that premature support for the CCP could jeopardize broader strategic objectives, including maintaining diplomatic relations with the internationally recognized Chinese government and preventing Western powers from replacing Chiang Kai-shek with someone even more hostile to Soviet interests.

World War II and Shifting Allegiances

The dynamics of Soviet support for Chinese factions underwent significant changes during World War II and its aftermath.

With Nazi Germany’s attack in June 1941, Soviet assistance to both Chinese parties almost completely ceased as Moscow focused on European survival. However, the end of the European war marked a dramatic shift in Soviet China policy.

Alongside mounting rapprochement between the KMT and the United States, Soviet support for the Chinese Communists increased substantially.

The August 14, 1945, Treaty of Friendship and Alliance between the Soviet Union and Chiang Kai-shek’s government proved to be the final chapter of Soviet-KMT cooperation rather than the beginning of a new partnership.

The Soviet occupation of Manchuria following Japan’s defeat provided a crucial turning point in the CCP's fortunes.

After liberation from Japanese forces, Red Army units temporarily stationed in northeastern China actively assisted the clandestine infiltration of Chinese Communists into the region and helped establish their revolutionary base.

The scale of Soviet assistance to the CCP in Manchuria was unprecedented, including the transfer of 861 airplanes, 600 tanks, artillery, mortars, 1,200 machine guns, rifles, and substantial ammunition stocks captured by Japanese forces.

This material support, combined with Soviet training of Chinese Communist military cadres and preferential loans for warfare, proved decisive in the CCP’s eventual victory in the Chinese Civil War.

Formation and Early Years of the Sino-Soviet Alliance (1950-1956)

The 1950 Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance

The establishment of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949 created the preconditions for a formal Sino-Soviet alliance, but the negotiations proved more complex than anticipated.

Mao Zedong’s visit to Moscow in late 1949 and early 1950 represented one of only two occasions when he left China, underscoring the enormous significance he attached to securing Soviet support.

The resulting Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Alliance, and Mutual Assistance, signed on February 14, 1950, created a thirty-year bilateral treaty of alliance, collective security, aid, and cooperation between the two communist giants.

The treaty emerged against Mao’s foreign policy directive of “leaning to one side” toward the socialist camp and Stalin’s strategic considerations regarding Soviet influence in East Asia.

Beyond the formal alliance provisions, the agreements included practical arrangements for the eventual restoration to complete Chinese control of the Chinese Changchun Railway, Port Arthur, and Dairen, as well as an extension by the Soviet Union of a $300-million credit over five years to the People’s Republic of China.

An additional exchange of notes provided for mutual recognition of the independence of the Mongolian People’s Republic, effectively legitimizing Soviet influence in this buffer state between China and the USSR.

However, Mao’s experience in Moscow revealed underlying tensions that later contributed to the alliance’s breakdown.

Despite achieving his primary objective of a formal alliance, Mao left Moscow feeling dissatisfied with Stalin’s dominant position in their partnership and the limited scope of Soviet financial support.

Stalin’s initial reluctance to sign a new treaty reflected his fear of losing Soviet privileges to use Lüshun (Port Arthur) and the China Eastern Railway, strategic assets crucial for Soviet access to the Pacific Ocean.

These infrastructure concessions had long been central to Russian and Soviet Far East security strategies.

Stalin eventually agreed to transfer them to China after extracting other concessions that preserved Soviet strategic interests in the region.

Early Cooperation and Hidden Tensions

The early years of the Sino-Soviet alliance witnessed substantial cooperation across multiple domains but also revealed the seeds of future discord.

The Korean War provided the first significant test of the alliance, with Stalin endorsing Kim Il-sung’s war plan during Mao’s Moscow visit.

Stalin’s decision to support North Korean aggression served multiple Soviet strategic objectives, including preventing the Chinese reclamation of full sovereignty over key strategic installations and ensuring Chinese dependence on Soviet support.

When Stalin later reneged on his promise of Soviet air support for Chinese forces in Korea, even if it meant giving up North Korea, this put Mao in an awkward position but demonstrated Soviet willingness to subordinate Chinese interests to broader strategic calculations.

The alliance provided China with crucial security guarantees and increased the scope of economic cooperation between the two countries.

Soviet technical assistance proved invaluable for Chinese industrialization efforts, while the security umbrella allowed China to focus on domestic reconstruction rather than external defense.

However, the relationship was fundamentally asymmetrical, with the Soviet Union maintaining the dominant position and China relegated to junior partner status. This dynamic became increasingly problematic as Chinese capabilities grew and Mao’s confidence in his revolutionary model increased.

The death of Stalin in 1953 created new uncertainties in the relationship. Still, the transition to collective leadership under figures like Nikita Khrushchev initially appeared to offer opportunities for more equal partnership.

However, Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization campaign and policy of peaceful coexistence with the West would soon create new sources of tension that proved irreconcilable with Chinese revolutionary objectives and Mao’s vision of continuous struggle against imperialism.

The Ideological Divergence and Growing Tensions (1956-1960)

Khrushchev’s De-Stalinization and Chinese Reactions

The fundamental break in Sino-Soviet relations began with Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Joseph Stalin in his 1956 speech “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences,” which initiated the de-Stalinization of the USSR.

Mao and the Chinese leadership were appalled by this development, as the PRC and USSR progressively diverged in their interpretations and applications of Leninist theory.

For Mao, Stalin’s legacy represented not only the success of socialist construction but also a validation of revolutionary methods that paralleled his approach to Chinese development.

Khrushchev’s critique of Stalin’s personality cult and authoritarian methods implicitly challenged the legitimacy of Mao’s leadership style and China’s development model.

The ideological disputes centered on competing interpretations of orthodox Marxism and practical applications of socialist theory.

Chinese leaders viewed Soviet policies of national de-Stalinization and international peaceful coexistence with the Western Bloc as revisionism that betrayed fundamental Marxist principles.

Against this ideological background, China took a belligerent stance toward the Western world and publicly rejected the Soviet Union’s policy of peaceful coexistence between the Western and Eastern Blocs.

The Chinese position reflected Mao’s belief that class struggle remained the driving force of historical development and that accommodation with capitalist powers represented ideological compromise rather than tactical flexibility.

By 1961, these intractable ideological differences provoked the PRC’s formal denunciation of Soviet communism as the work of “revisionist traitors” in the USSR.

The PRC also declared the Soviet Union to be “social imperialist,” a term that implied the Soviet Union had abandoned socialist principles while maintaining imperialist ambitions.

This rhetoric escalated the dispute beyond policy disagreements to fundamental questions about the nature of socialism and the legitimate leadership of the international communist movement.

The struggle over interpretive authority became central to the conflict, as both parties understood that “only when a party had the authority to interpret Marxism could it be the legitimate leader of the movement.”

Personal Conflicts and Diplomatic Humiliations

Personal animosity between Mao and Khrushchev exacerbated the ideological tensions and contributed to the breakdown of formal diplomatic relations.

The famous swimming pool incident during Khrushchev’s 1958 visit to Beijing exemplified the deteriorating personal relationship between the two leaders. Mao, an accomplished swimmer, invited Khrushchev to swim together, knowing that the Soviet leader could not swim.

This humiliation reflected Mao’s intention to place himself in an advantageous position during their negotiations, leading Khrushchev to recall later: “It was Mao’s way of putting himself in an advantageous position. Well, I got sick of it”.

The final face-to-face meeting between Mao and Khrushchev took place on October 2, 1959, during Khrushchev’s visit to Beijing to mark the 10th anniversary of the Chinese Revolution.

By this point, relations had deteriorated, so the Chinese deliberately humiliated the Soviet leader through various diplomatic slights.

There was no honor guard to greet Khrushchev, no Chinese leader gave a welcoming speech, and no microphone was provided when Khrushchev insisted on giving his speech.

The speech praised US President Eisenhower, whom Khrushchev had recently met, representing a blatant intentional insult to Communist China.

These personal humiliations reflected the broader breakdown in trust and respect between the two communist powers.

The deterioration of personal relationships between leaders had profound implications for state-to-state relations.

The leaders of the two socialist states would not meet again for the next thirty years, effectively ending high-level diplomatic communication at the most critical period of their relationship.

This breakdown in personal diplomacy meant that subsequent disputes could not be resolved through direct negotiation, escalating tensions into military confrontation.

Competing Claims to Revolutionary Leadership

The dispute over leadership of the international communist movement became increasingly central to Sino-Soviet tensions throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s.

For Eastern Bloc countries, the Sino-Soviet split posed fundamental questions about “who would lead the revolution for world communism, and to whom (China or the USSR) the vanguard parties of the world would turn for political advice, financial aid, and military assistance.”

Both countries competed for influence through vanguard parties native to countries in their respective spheres of influence, transforming ideological disputes into geopolitical competition.

The 1960 International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties in Bucharest became a crucial battleground for this competition.

Mao and Khrushchev attacked Soviet and Chinese interpretations of Marxism-Leninism as the wrong road to world socialism, making their disagreement public before the entire international communist movement.

Mao argued that Khrushchev’s emphasis on consumer goods and material plenty would make the Soviets ideologically soft and un-revolutionary, to which Khrushchev replied: “If we could promise the people nothing, except revolution, they would scratch their heads and say: ‘Isn’t it better to have good goulash?’”.

This exchange encapsulated the fundamental disagreement between the Chinese emphasis on revolutionary purity and the Soviet focus on material improvement as the basis for socialist legitimacy.

The Albanian factor further complicated the competition for communist leadership.

Albania, upset with Khrushchev’s leadership of the USSR, allied with the Chinese, providing Beijing with a European foothold in the communist world.

The Albanians and Chinese jointly condemned the CPSU’s new program as effectively “putting an end to domestic class struggle and the dictatorship of the proletariat” and labeled it “revisionist.”

This alliance demonstrated China’s ability to challenge Soviet hegemony within the communist bloc and provided a precedent for other communist parties to choose sides in the growing dispute.

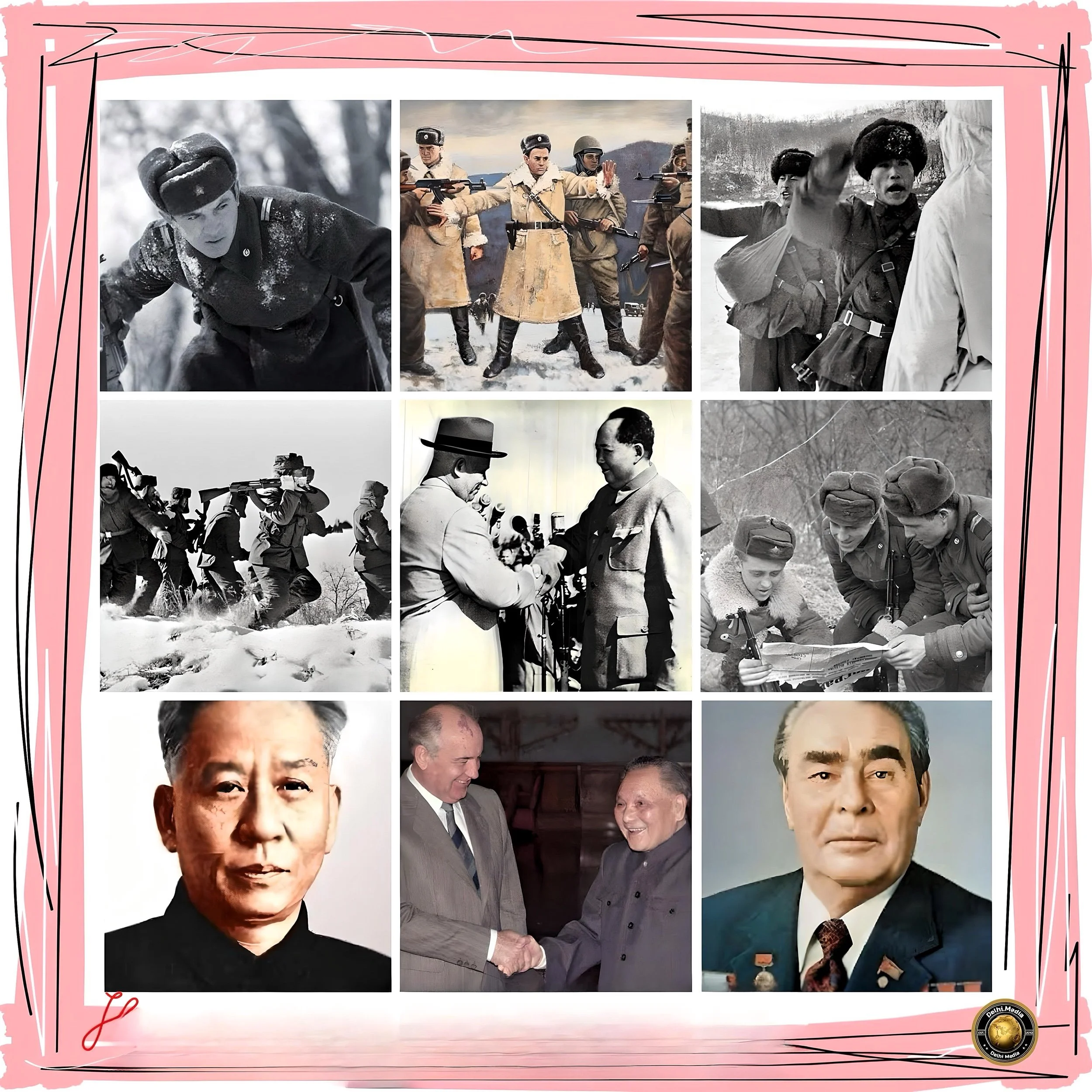

Border Conflicts and Military Confrontation (1960-1969)

Escalation of Territorial Disputes

The ideological disputes between China and the Soviet Union gradually escalated into territorial conflicts that brought the two nuclear powers to the brink of war.

In 1966, the Chinese government revisited the national matter of the Sino-Soviet border demarcated in the 19th century. This border had been initially imposed upon the Qing dynasty through unequal treaties that annexed Chinese territory to the Russian Empire.

Despite not demanding the return of territory, the PRC asked the USSR to acknowledge formally and publicly that the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Convention of Peking dishonestly realized the historical injustice of the 19th-century borde.

The Soviet government’s decision to ignore this matter reflected Moscow’s unwillingness to acknowledge any legitimacy to Chinese territorial grievances.

The militarization of the border began in earnest during the early 1960s, with both sides dramatically increasing their military presence along the 4,380-kilometer frontier. In 1961, the USSR had stationed 12 divisions of soldiers and 200 airplanes at the border.

By 1968, the Soviet Armed Forces had deployed six divisions in Outer Mongolia and 16 divisions, 1,200 airplanes, and 120 medium-range missiles specifically positioned to confront 47 light divisions of the Chinese Army along the Sino-Soviet border.

This massive military buildup reflected both sides’ preparation for potential armed conflict and demonstrated how ideological disputes had transformed into strategic military competition.

The Soviet military posture particularly concerned Chinese leaders regarding the Xinjiang frontier in northwest China, where the Soviets were positioned to induce Turkic peoples into separatist insurrection readily.

This geographical vulnerability highlighted China’s strategic weakness in defending its vast western territories against Soviet pressure.

The demographic composition of Xinjiang, with its large Turkic population and historical connections to Central Asia, made it particularly susceptible to Soviet influence and potential territorial dismemberment.

The Zhenbao Island Incident and Military Clashes

The most serious border confrontation occurred in March 1969 at Zhenbao (Damansky) Island on the Ussuri River in Manchuria. This clash brought the world’s two largest socialist states to the brink of all-out war and demonstrated how territorial disputes could escalate beyond diplomatic control.

The incident began when a group of People’s Liberation Army troops engaged Soviet border guards on the disputed island, resulting in considerable casualties on both sides.

The fighting represented the culmination of years of increasing border tensions and provided both sides with a pretext for further military escalation.

Additional clashes occurred in August 1969 at Tielieketi in Xinjiang, raising the prospect of an all-out nuclear exchange between the two communist powers.

These western border incidents demonstrated that the conflict extended beyond the eastern frontiers to encompass the entire length of the Sino-Soviet border.

The geographic spread of confrontations indicated systematic rather than accidental military engagement, suggesting both sides were prepared to use force to defend their territorial claims.

The severity of the 1969 border conflict extended beyond conventional military engagement to include the prospect of nuclear warfare.

The Soviet Union planned to launch a large-scale nuclear strike on China, including its capital, Beijing but eventually called off the attack due to intervention from the United States.

This near-nuclear confrontation revealed how completely the Sino-Soviet relationship had broken down and demonstrated the global implications of their dispute.

The United States' role in preventing a Soviet nuclear attack on China foreshadowed the eventual Chinese-American rapprochement that would reshape Cold War dynamics.

Intelligence Wars and Continued Tensions

Following the border conflicts, “spy wars” involving numerous espionage agents occurred on Soviet and Chinese territory throughout the 1970s.

These intelligence operations reflected the continuation of hostilities through clandestine means and demonstrated both sides’ commitment to gaining strategic advantages over their former ally.

The espionage activities encompassed military intelligence and political and economic information gathering, indicating the rivalry's comprehensive nature.

In 1972, the Soviet Union renamed place names in the Russian Far East to Russian language and Russified toponyms, replacing native and Chinese names.

This cultural and linguistic assertion of Soviet sovereignty represented symbolic warfare to eliminate Chinese historical claims to Far Eastern territories.

The toponymic changes reflected broader Soviet efforts to consolidate territorial control and eliminate potential sources of Chinese irredentist claims.

The crisis eventually de-escalated after Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin met with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in September 1969, leading to a ceasefire and return to the status quo ante bellum.

However, this tactical de-escalation did not resolve the underlying territorial disputes or restore normal diplomatic relations.

Sino-Soviet relations remained severely strained despite reopening border negotiations, which continued inconclusively for a decade without substantial progress.

Strategic Realignment and Cold War Implications (1969-1991)

The China-US Rapprochement

The Sino-Soviet border conflict fundamentally altered global Cold War dynamics by creating opportunities for Chinese-American cooperation against their common Soviet adversary.

To counterbalance the Soviet threat, the Chinese government actively sought rapprochement with the United States. This strategic realignment represented a dramatic reversal of Chinese foreign policy and demonstrated the primacy of geopolitical calculations over ideological considerations in international relations.

The diplomatic breakthrough began with Henry Kissinger’s secret visit to China in 1971, which paved the way for President Richard Nixon’s official visit to China in 1972.

These initiatives represented the most significant Cold War realignment since the formation of the NATO and Warsaw Pact alliances and fundamentally altered the global balance of power.

The Chinese-American rapprochement created a triangular relationship that gave both Beijing and Washington leverage against Moscow while forcing the Soviet Union to confront potential enemies on multiple fronts.

Khrushchev and Mao's stormy October 1959 meeting revealed the Soviet willingness to blame China for international tensions, including conflicts with India. During their confrontation, Khrushchev stated, “If you let me, I will tell you what a guest should not say: the events in Tibet are your fault.”

When discussing border clashes with India, Khrushchev blamed the Chinese for killing Indian soldiers, to which Mao replied, “They attacked us first, crossed the border, and continued firing for twelve hours.”

These exchanges demonstrated how the Sino-Soviet split created opportunities for Moscow’s regional partners while constraining Chinese diplomatic options.

Long-term Consequences for International Relations

The Sino-Soviet split created lasting changes in international relations that extended beyond the bilateral relationship between Beijing and Moscow.

The breakdown of communist unity fundamentally altered the Cold War from a bipolar confrontation between capitalism and socialism to a more complex triangular relationship involving the United States, the Soviet Union, and China.

This transformation gave smaller nations greater diplomatic flexibility and reduced the ideological coherence of both the Western and Eastern blocs.

The split also established precedents for using bilateral relationships to hedge against third parties.

This strategy dominated Moscow and Beijing’s triangular diplomacy with Washington until the outbreak of the contemporary U.S.-China competition and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

This hedging approach allowed China and Russia to limit their growing reliance on the West while gaining leverage over the United States without fully committing to a close partnership.

For the international communist movement, the Sino-Soviet split created permanent divisions that undermined efforts to present a unified alternative to Western capitalism.

Communist parties worldwide were forced to choose between Chinese and Soviet interpretations of Marxism-Leninism, weakening the movement’s overall coherence and effectiveness.

The split demonstrated that national interests could override ideological solidarity even among communist states committed to the same basic principles.

Gradual Normalization Under Gorbachev

The eventual normalization of Sino-Soviet relations required fundamental changes in Soviet leadership and foreign policy approach.

Mikhail Gorbachev played a crucial role in removing the “three obstacles” to improved relations that Beijing had identified: the presence of Soviet troops on China’s northern border, Soviet support for Vietnam, particularly in Cambodia, and the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

Gorbachev’s willingness to make these concessions, which his predecessors had refused, reflected Soviet domestic priorities and recognition of China’s growing international importance.

The normalization process culminated in Gorbachev’s visit to Beijing in May 1989, during which he met with Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Communist Party leadership.

While overshadowed by the Tiananmen protests and lacking immediate concrete deliverables, the visit represented a significant diplomatic success that concluded years of careful negotiations by both sides.

The timing of Gorbachev’s visit during the student demonstrations strengthened bilateral relations. Gorbachev avoided criticism of the Chinese government and firmly opposed Beijing’s position on Taiwan.

The normalization also initiated a process of resolving the territorial dispute that had poisoned relations for decades.

An agreement reached in 1991 during the final days of Gorbachev’s rule spearheaded the resolution process. Additional contracts signed in 2004 and 2008 fully settled the dispute and demarcated the border between Russia and China.

The gradual removal of this century-old obstacle significantly facilitated closer relations between Moscow and Beijing in the post-Cold War era.

Impact on Modern China-Russia Relations (2025)

Strategic Lessons and Current Alignment

Flexible Cooperation

Unlike the rigid alliance of the 1950s, the current China-Russia relationship is characterized by a flexible, strategic partnership rather than a formal military alliance.

This allows both countries to cooperate closely in military, economic, technological, and political domains while maintaining independence in foreign policy decisions.

Opposition to the West

Both countries share a desire to challenge the US-led global order.

Their cooperation is driven by mutual interests in energy, security, and maintaining stability in Central Asia rather than ideological solidarity.

Avoiding Past Mistakes

The bitter experience of the Sino-Soviet split taught both sides the risks of ideological rigidity and the dangers of open confrontation.

Today, they manage disagreements carefully, understanding that conflict would only benefit third parties.

Economic and Military Interdependence

Energy and Trade

Russia is a major energy supplier to China, which is a key market for Russian exports.

The countries have deepened their economic ties, especially after Western sanctions on Russia and trade tensions involving China.

Military-Technical Cooperation

China benefits from Russian military technology, and both countries conduct joint military exercises, signaling their close defense ties.

Geopolitical Calculus and Global Influence

War in Ukraine

China’s support for Russia in the context of the Ukraine war demonstrates the depth of their strategic partnership, but it is not unconditional.

China maintains a degree of independence, carefully calibrating its support to avoid international isolation and sanctions.

Learning from History

The legacy of the Sino-Soviet split informs contemporary Chinese and Russian leaders’ caution against over-reliance on each other and the importance of pragmatic, interest-based cooperation.

The Sino-Soviet Alliance and Split are vital for understanding the current China-Russia relationship.

The alliance laid the groundwork for cooperation, while the split demonstrated the dangers of ideological rigidity and national rivalry.

Today, both countries leverage their historical experiences to build a pragmatic, flexible, and strategically vital partnership, united by shared opposition to Western dominance but cautious of repeating past mistakes

Conclusion

The evolution of Sino-Soviet relations, from an initial alliance to confrontation and subsequent normalization, highlights critical international relations dynamics beyond mere ideological frameworks.

In the early stages, the Soviet Union's support for various Chinese factions demonstrated a pragmatic foreign policy approach, prioritizing strategic interests over ideological coherence.

Although the Soviet leadership backed the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), its underlying aim was to advance Russian geopolitical objectives, particularly concerning access to the Pacific and the establishment of buffer zones against perceived threats.

The 1950 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship represented the pinnacle of communist collaboration, yet the inherent contradictions within this partnership rendered its dissolution almost inevitable.

The relationship's asymmetry, characterized by China's subordinate role despite its burgeoning demographic and military capabilities, fostered resentments that ideological ties could not sufficiently mitigate.

Personal rivalries, especially the deep-seated animosity between Mao Zedong and Nikita Khrushchev, intensified policy disagreements into profound hostility and complicated opportunities for diplomatic resolution.

Additionally, ideological schisms in the post-Stalin era exposed diverging visions of socialist development and global strategy, reflecting fundamentally different national interests and cultural paradigms.

China’s commitment to revolutionary zeal and ongoing class struggle starkly contrasted with the Soviet Union's inclination toward stability and material progress, making compromise increasingly elusive.

Moreover, the contest for leadership within the global communist movement transitioned bilateral tensions into broader challenges that threatened the cohesion of the socialist bloc.

The near-confrontations during the Sino-Soviet border conflict in 1969 starkly illustrated how ideological divisions could escalate to the brink of a nuclear confrontation between former allies, marking a complete disintegration of socialist unity.

The subsequent rapprochement between China and the United States fundamentally transformed the Cold War landscape, establishing a framework of triangular diplomacy still relevant in contemporary international relations.

The normalization process under Mikhail Gorbachev required significant shifts in Soviet priorities, reflecting the potential to overcome deeply rooted historical animosities through strategic diplomacy and mutual concessions.

Ultimately, the Sino-Soviet narrative encapsulates the limitations of ideological congruence in sustaining international partnerships when foundational national interests diverge.

The trajectory from cooperation to conflict to normalization mirrors broader trends in international relations and underscores the preeminence of geopolitical imperatives over ideological affiliations.

This historical context is essential for a nuanced understanding of contemporary Sino-Russian relations and their implications for global stability amidst a resurgence of great power competition.