History of Persian Civilization and Iran’s Modern Political Trajectory

Introduction

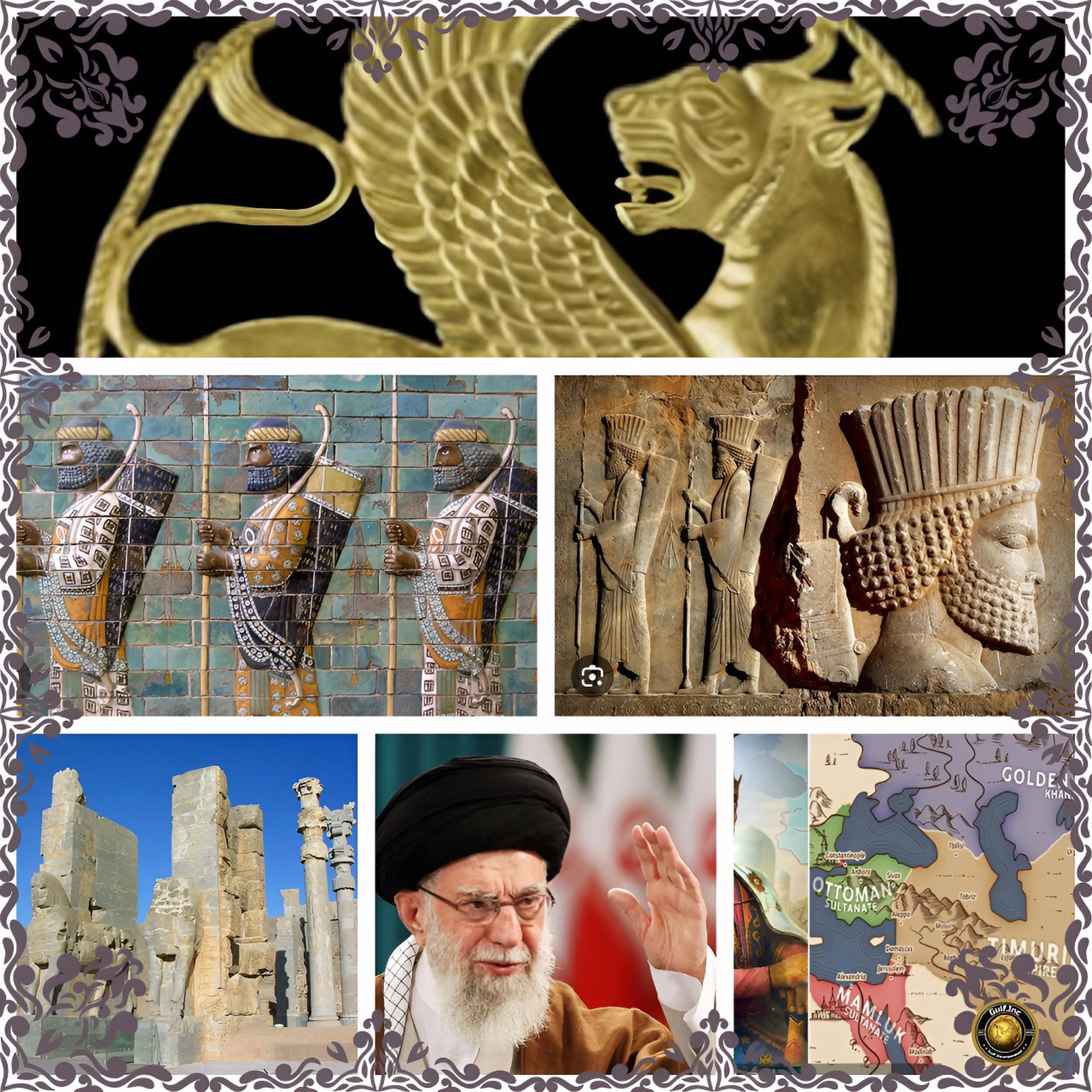

Ancient and Classical Persian Civilization

Foundational Heritage: The 2,500-Year Continuum

Persian civilization represents one of the world’s oldest continuous civilizations, with its origins predating the classical Persian empires.

Before the emergence of the Persians themselves, the Elamites flourished in southwestern Iran from approximately 2700 BCE, establishing one of humanity’s oldest civilizations and creating independent language systems and cultural identities.

The subsequent Indo-European migration brought the Medes and Persians to the Iranian plateau around 1500 BCE, fundamentally reshaping the region’s cultural and linguistic landscape.

The foundation of Classical Persian power emerged with the Median Empire under King Cyaxares around 625 BCE, who revolutionized regional warfare through military specialization and hierarchical organization—innovations that would become hallmarks of Persian military supremacy.

The definitive moment came in 550 BCE when Cyrus the Great founded the Achaemenid Empire, establishing the first truly multinational empire and creating unprecedented administrative structures.

At its zenith, the Achaemenid Empire controlled approximately 44% of the world’s population, spanning three continents.

The Achaemenid period established enduring Persian traditions including the promotion of cultural diversity through tolerance of local customs and religions, principles exemplified by Cyrus the Great’s liberation of enslaved peoples and the issuance of what some scholars consider the first declaration of human rights.

The empire maintained extraordinary longevity through administrative sophistication, sophisticated postal systems, and the use of Aramaic as a lingua franca facilitating commerce and governance across vast territories.

Following the Macedonian conquest and subsequent fragmentation, the Parthian Empire (247 BCE–224 CE) sustained Persian cultural identity while becoming a critical intermediary in the Silk Road trade networks, facilitating the first truly global commerce network connecting East and West.

Chinese historical records documented these exchanges, cementing the Parthians’ role as global players millennia before modern globalization.

The Sassanid Empire (224–651 CE) represented the final pre-Islamic Persian dynasty, distinguished by highly centralized state organization under direct royal authority and deliberate revival of ancient Persian cultural traditions.

The Sassanids established sophisticated administrative systems, developed Zoroastrianism as a state religion, and created remarkable artistic and architectural achievements.

Their forty-year conflict with Byzantine forces left the empire weakened, ultimately enabling Arab Muslim conquest between 636 and 651 CE.

Islamic Conquest and Cultural Synthesis

The Islamic conquest represented the most fundamental transformation in Persian history, yet paradoxically strengthened rather than eliminated Persian identity.

Rather than passive submission, Persians synthesized Islamic civilization with pre-Islamic Persian cultural memory, administrative sophistication, and intellectual traditions.

Persian became the literary language of Islamic courts, Persian poets dominated Islamic poetry, and Persian administrators staffed Islamic bureaucracies.

The integration proved so thorough that “Islamic civilization” became substantially Persian in its intellectual and cultural expression, despite Arab political dominance.

Modern Iranian History: The Emergence of Contemporary Political Issues

The Qajar Dynasty and the Birth of Modern Iran (1796-1925)

Modern Iranian political complexity emerged during the Qajar period, when Iran faced unprecedented external pressure from European imperial powers.

The Russo-Persian Wars resulted in territorial losses and indemnities, creating nationalist sentiment and tension between modernization advocates and traditional elites.

The Constitutional Revolution of 1906 represented Iran’s first attempt at constitutional governance, establishing a parliament (Majlis) and written constitution limiting monarchical power—a remarkable achievement for the region at that time.

The Pahlavi Era and State Modernization (1925-1979)

Reza Shah Pahlavi’s rise in the 1920s initiated aggressive modernization programs inspired by Atatürk’s Turkey, including centralization of state power, military expansion, and secular institutional development.

His son, Mohammad Reza Shah, inherited this modernization project but accelerated it during the post-World War II period.

The Shah’s 1951 attempt to nationalize oil—executed by Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh—represented genuine nationalist assertion but provoked international intervention.

The 1953 CIA-backed coup reversed nationalization, restored the Shah to power, and created enduring resentment toward Western intervention, particularly American involvement.

Despite modernization achievements, the Shah’s regime increasingly relied on authoritarian repression through the secret police (SAVAK), created political alienation across diverse segments of Iranian society, suppressed civil society organizations, and implemented media censorship and systematic targeting of political opponents.

The government’s pro-Western modernization, rapid industrialization despite unequal wealth distribution, oil boom exacerbating economic disparities, and perceived cultural Westernization created widespread discontent spanning secular nationalists, religious conservatives, and communist-oriented groups.

The White Revolution of 1963, intended to modernize rural Iran through land reform, women’s rights expansion, and industrial development, paradoxically accelerated revolution by displacing traditional landholding elites and provoking clerical opposition.

Ayatollah Khomeini’s June 1963 uprising against the Shah and White Revolution resulted in his exile to Iraq, transforming him into a revolutionary symbol while he orchestrated opposition from abroad.

The 1979 Iranian Revolution: Rupture and Reconstruction

Revolutionary Transformation

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 fundamentally restructured Iran’s political system, ending the monarchy after 2,500 years of Persian imperial tradition and replacing it with an Islamic theocratic republic.

The revolution’s coalition encompassed liberals, communists, secular nationalists, and Islamists, but clerical factions proved most organizationally cohesive and ideologically decisive.

Ayatollah Khomeini, returning from exile on February 1, 1979, became the undisputed revolutionary leader and developed the doctrine of velayat-e faqih (governance of the jurist), concentrating sweeping powers in the hands of the supreme leader.

Post-revolutionary consolidation proved brutal and ideologically transformative.

Revolutionary tribunals executed former officials, military personnel, and perceived counterrevolutionaries without due process; the 1979-1981 period witnessed systematic liquidation of non-Islamist revolutionary factions including monarchists, liberals, communists, and ethnic minority movements.

The takeover of the U.S. Embassy (November 1979), the 444-day hostage crisis, and the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) transformed Iran into an embattled revolutionary state defining itself through anti-Western, anti-Israeli resistance.

The Islamic Republic abandoned Iran’s earlier secular modernization trajectory, reoriented foreign policy around revolutionary Islamic ideology and Persian Gulf regional hegemony, and established institutional mechanisms perpetuating clerical control through the Revolutionary Guard (IRGC), intelligence apparatus, and parallel governance structures operating alongside constitutional institutions.

Modern Political Institutions and Constraints

The Islamic Republic’s political system creates persistent structural tensions. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (successor to Khomeini since 1989) possesses ultimate authority over military, judiciary, state media, and intelligence apparatus, while theoretically constrained by a president, parliament, and assembly of experts.

However, effective power concentration in the supreme leader’s hands severely limits meaningful democratic evolution.

The Guardian Council, dominated by clerics, vets political candidates and laws, ensuring ideological conformity and removing genuine reform possibilities.

Presidents from Khatami (1997-2005) through moderate Masoud Pezeshkian (elected 2024) have attempted reforms while constrained by Supreme Leader authority and IRGC institutional interests.

The IRGC, originally created as revolutionary vanguard, evolved into massive economic actor controlling extensive commercial enterprises, military-industrial sectors, and strategic resources—creating incentive structures favoring regime preservation over democratic opening.

Emergence and Persistence of Contemporary Political Issues

The Nuclear Program: From National Pride to International Flashpoint

Iran’s nuclear program, initiated in the 1950s with American assistance under the Shah, transformed into a symbol of national scientific achievement and independence following the revolution.

During the 1980s Iran-Iraq War, Iraq’s chemical weapon attacks motivated nuclear weapons consideration.

The program expanded through the 1990s with Russian and Chinese assistance, remaining undeclared until 2002 when dissident groups revealed clandestine enrichment facilities at Natanz and Arak.

International concern escalated significantly after 2002, with the United States and Israel viewing nuclear development as existential threat, while Iran maintained civilian energy justifications.

The 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) represented diplomatic breakthrough, with Iran accepting limitations on enrichment, transparent inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and sanctions relief.

However, U.S. President Trump’s 2018 withdrawal reintroduced sanctions, accelerating Iran’s enrichment expansion beyond JCPOA limits.

As of 2025, the nuclear crisis has reached unprecedented escalation.

On June 12, 2025, the IAEA found Iran non-compliant for the first time in 20 years. Israel responded with large-scale strikes on June 13, 2025, damaging multiple Iranian nuclear sites, followed by U.S. bombardment on June 21.

Iran retaliated with unprecedented missile attacks, breaching Israeli air defenses and striking military installations.

The crisis escalated further when Iran signed law suspending IAEA cooperation, signaling potential Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) withdrawal.

This nuclear escalation has catastrophic implications

IAEA inspections cessation creates accountability gaps regarding Iranian nuclear activities; intelligence disputes among international powers risk miscalculation and further conflict; potential Iranian NPT withdrawal would eliminate international legal frameworks constraining proliferation; regional domino effects could trigger Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and other states toward weapons development.

Regional Influence and Proxy Network

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran invested systematically in regional military networks through the IRGC’s Quds Force, creating allied armed groups across the Middle East—Hezbollah in Lebanon, various militias in Iraq, Houthi forces in Yemen, and armed Palestinian factions.

This network served Iranian strategic objectives of countering Israeli and American influence while projecting regional power through non-state proxies, effectively multiplying Iranian military reach without conventional military superiority.

However, Iran’s regional position has undergone dramatic deterioration since October 2023.

The Gaza conflict, Israeli military operations in Lebanon eliminating Hezbollah leadership, and Syrian civil war’s resolution with Assad’s fall (December 2024) have severely weakened Iran’s regional network.

The June 2025 Israel-Iran war and subsequent regional reconfiguration have devastated Iran’s four-decade accumulation of regional influence.

Iran’s Contemporary Political Landscape (2025)

Internal Dynamics and Reform Constraints

Iran’s current political situation presents contradictions: reformist President Pezeshkian, elected in July 2024 following hardline President Raisi’s death, promises economic recovery and diplomatic engagement, yet operates within structural constraints imposed by Supreme Leader Khamenei and IRGC institutional interests.

Pezeshkian’s agenda emphasizing nuclear diplomacy, economic stabilization, and social liberalization confronts conservative institutional resistance, limited presidential authority, and geopolitical volatility from the Israel-Iran conflict.

Civil Society and Popular Discontent

Despite regime repression, persistent protest movements challenge Islamic Republic legitimacy.

The 2022-2023 “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests following Mahsa Amini’s death represented “the biggest challenge” to the government since 1979, with at least 551 killed by security forces and estimated 19,262 arrested.

Distinct from previous protests focused on elections or economics, these demonstrations explicitly demanded regime overthrow and targeted mandatory hijab enforcement, representing generational challenge from younger Iranians experiencing repression differently than their parents.

The regime responded with intensified coercive measures, reinstating morality police patrols, implementing severe penalties for unveiled women (up to 10 years imprisonment), shuttering establishments violating hijab enforcement, and systematic arrests of protesters and families.

Yet underground resistance continues through underground journalism, diaspora networks, and civil society organizations despite operational constraints.

Women face particularly severe conditions: official unemployment for women aged 20-24 reaches 34.9%, double or triple male equivalents; women represent 42% of university graduates yet face systemic discrimination in hiring; gender apartheid laws restrict women’s rights in marriage, divorce, inheritance, child custody, employment, and political participation.

For women, Iran’s theocratic system represents systematic state-sponsored subjugation institutionalized through law and policy.

Youth unemployment broadly reaches 50-63% in some regions, with 42% of unemployed possessing university degrees, indicating severe mismatch between educational systems focused on ideological indoctrination (mandatory Islamic education, Quranic studies, Khomeini’s teachings) and actual labor market requirements.

Brain drain accelerates as educated Iranians emigrate seeking better opportunities.

Iran’s Economic Crisis and Future Development Prospects

Current Economic Catastrophe

Iran’s economy faces simultaneous recession and hyperinflation following October 2025 UN sanctions reimposition.

The World Bank forecasts economic contraction of 1.7% in 2025 and 2.8% in 2026, representing dramatic reversal from modest growth projections.

The Iranian rial plummeted from 920,000 per dollar in August 2025 to 1.1 million per dollar by October—a 19.6% depreciation in two months alone.

Inflation rates reach 40-50% officially, eroding household purchasing power and devastating fixed-income earners and middle-class households.

Oil exports, constituting approximately 25% of GDP, face renewed constraints as sanctions limit international customers beyond China.

Each dollar decrease in crude oil prices translates to roughly $500 million in annual revenue losses for Iran.

China, Iran’s largest remaining oil buyer, faces pressure to reduce imports or demand steeper discounts to avoid U.S. confrontation, potentially devastating Iran’s trade revenues.

The “resistance economy” strategy—emphasizing self-sufficiency and enhanced trade with Russia, China, and regional states—offers limited relief.

Despite Russia-Iran cooperation and China’s continued engagement, these partnerships cannot compensate for lost Western trade networks, disrupted financial systems, constrained shipping, and comprehensive international isolation.

Economic Constraints on Political Reform

Economic collapse directly undermines potential political transition.

The government holds emergency meetings attempting to avert economic collapse and contain public anger, yet officials privately admit “protests are inevitable” as unemployment rises, inflation accelerates, and state capacity deteriorates.

Paradoxically, the economic pressures threatening regime stability through potential popular mobilization simultaneously strengthen security apparatus resistance to political liberalization, as security forces perceive democratic opening as existential threat requiring intensified repression.

Prospects for Iran’s Future: 2025-2035

Political Stability Outlook

Pessimistic Scenario: Continued Authoritarian Entrenchment

Multiple indicators suggest entrenched authoritarian persistence despite reform rhetoric.

Khamenei’s institutional power remains overwhelming, the IRGC controls critical military and economic sectors, the Guardian Council filters all meaningful political participation, and security apparatus possesses demonstrated willingness for systematic violence against dissidents.

The 2022-2023 Mahsa Amini protests, despite unprecedented scale and explicitly revolutionary demands, failed to produce regime change, with security forces killing hundreds and arrests exceeding 19,000, ultimately leaving “political leadership unchanged and firmly entrenched in power.”

Pezeshkian’s reformist mandate faces severe practical constraints.

As president, he lacks authority over military (IRGC), judiciary, state media, and intelligence—domains under Supreme Leader control.

While Pezeshkian could potentially implement modest economic liberalization and cautious social reforms, fundamental political restructuring remains institutionally impossible without Khamenei’s consent, which would constitute his own power relinquishment.

The recent military defeats and regional strategic reversals paradoxically may strengthen repressive capacity rather than encourage democratic opening, as security establishment perceives regime survival threatened by both external military pressure and internal dissent, creating logic for intensified control rather than liberalization.

Historical authoritarian theory suggests regimes under existential threat typically respond through repression maximization, not democratization.

Optimistic Scenario: Reform Opening and Democratic Transition

However, precedents exist for authoritarian collapse under military defeat combined with sustained civil society pressure.

Portugal’s Carnation Revolution (1974) and Greece’s transition from authoritarianism (1974) occurred following military defeats eroding regime legitimacy, coupled with civil society mobilization.

The Mahsa Amini protests demonstrated unprecedented willingness among Iranian youth, women, and minorities to demand fundamental regime change—representing generational consciousness distinct from their parents’ revolutionary experience.

The demographic trend toward greater age diversity, university education expansion (despite ideological indoctrination), and internet connectivity despite censorship efforts have created information access and youth empowerment that constrain regime legitimacy.

The expansion of international diaspora networks, cultural production in exile, and transnational civil society organizations create pressure points and alternative Iranian identity sources the state cannot fully control.

Potential reform pathways could emerge if:

(1) economic crisis intensifies to degree forcing regime negotiation with international community as survival strategy.

(2) factional divisions within political elite create opening for reformist elements to assert greater authority

(3) accumulated civil society pressure achieves critical mass despite repression.

(4) generational succession following Khamenei’s eventual death creates transition opportunity.

Economic Development Prospects

Structural Economic Barriers

Iran’s economic future confronts fundamental obstacles unlikely to resolve within the decade without dramatic geopolitical transformation:

Sanctions persistence

Oil sanctions, banking restrictions, shipping constraints, and financial system isolation constitute deep structural barriers lasting beyond any single negotiation.

Even under optimal diplomatic outcomes, sanctions removal requires prolonged negotiation and verification periods potentially spanning years.

Oil sector constraints

Global energy transition toward renewables and electric vehicles structurally reduces long-term demand for petroleum, potentially undermining Iran’s primary export revenue regardless of sanctions status.

Additionally, Iran’s oilfields face technical aging and require substantial investment for maintenance, capital Iran lacks due to sanctions and capital flight.

Demographic liabilities

Youth unemployment reaching 50-63% reflects not just cyclical recession but structural educational-labor market mismatch and lack of job creation capacity.

Rapid aging (median age projected 35.5 by 2025) will increase dependency ratios and healthcare costs precisely when fiscal resources contract.

Brain drain acceleration

Hundreds of thousands of educated Iranians have emigrated since 2019, removing precisely the human capital necessary for economic modernization.

This exodus accelerates during economic crisis and political uncertainty, creating self-reinforcing cycle of declining capacity.

Institutional capacity deficiencies

Corruption, nepotism, regime-favoring business allocation, and IRGC commercial dominance create misallocation of resources and inefficient capital deployment.

These pathologies reflect systemic institutional design rather than temporary policy failures, requiring fundamental restructuring.

Regional Influence and Strategic Positioning

Dramatic Regional Decline

Iran’s regional position has undergone catastrophic transformation in 2024-2025.

The fall of Assad in Syria (December 2024) eliminated Iran’s primary regional ally and military foothold, Hezbollah’s decimation in Lebanon (2024) eliminated the centerpiece of Iranian proxy networks, Gaza conflict depletion of Hamas capabilities, Houthi military exhaustion, and Iraqi government distancing from Iran have systematically dismantled four decades of Iranian regional influence construction.

Multiple analysts characterize this period as Iran’s “Regional Autumn,” with one assessment noting Iran “now finds itself gravely weakened on every front, emerging from this prolonged confrontation with deep and visible wounds” and that “since its founding in 1979, the regime has never appeared so vulnerable.”

The erosion extends beyond military calculations to regime legitimacy, as core revolutionary ideology justifying clerical rule centered on “anti-imperialism” through regional resistance—a narrative loses persuasiveness when resistance fails systematically.

Eastward Pivot and BRICS Integration

Confronting Western isolation, Iran has accelerated eastward strategic reorientation through 25-year China cooperation agreement, 20-year Russia strategic partnership, accession to BRICS (2023), Shanghai Cooperation Organisation membership, and observer status in Eurasian Economic Union.

The International North-South Transport Corridor through Iran and operational role at Chabahar Port reflect connectivity infrastructure development toward Asian markets.

However, these partnerships offer limited substitutes for Western integration.

China and Russia prioritize their own interests above Iran’s, willing to reduce Iranian oil purchases if advantageous geopolitically, as demonstrated by China’s previous oil import reductions under Trump pressure.

Neither provides the capital investment, technology transfer, or market access that Western integration would enable.

Additionally, these partnerships typically accommodate rather than oppose U.S. interests when strategic calculation favors accommodation, leaving Iran vulnerable to external actor interests rather than advancing genuine independence.

Military and Security Dynamics

Persistent Confrontation with Israel and United States

The 2025 military escalation demonstrates unprecedented willingness for direct Israeli-U.S.-Iran conflict.

Israel’s June 13, 2025 strike and U.S. June 21, 2025 bombardment of Iranian nuclear facilities marked qualitative escalation from decades of covert operations toward overt military confrontation.

Iranian retaliation through coordinated missile attacks, though ultimately intercepted, demonstrated unprecedented capability and willingness for direct response.

Major General Mohsen Rezaei’s September 2025 warning that any new Israeli strike would trigger comprehensive war involving the U.S. indicates Iranian leadership perception of uncontrollable escalation risk, suggesting deterrence calculus has fundamentally shifted.

However, this deterrence currently rests primarily on missile capability and threatened economic disruption through regional conflict, not military symmetry or capacity to inflict unacceptable costs.

Over the next decade, military technological gaps between Iran and Israel/U.S. will likely widen, as Israel receives cutting-edge American systems while Iran faces sustained arms embargoes.

This technological asymmetry constrains Iran’s capacity to sustain regional deterrence, potentially creating logic for either nuclear weapons development (enhancing deterrence through non-conventional capacity) or strategic accommodation with regional rivals accepting reduced influence.

Nuclear Program’s Role in Future Trajectory

The nuclear program will remain Iran’s most consequential policy domain. Three scenarios merit consideration:

Scenario 1

Continued Escalation

Iran resumes robust enrichment, potentially withdraws from NPT, and develops weapons capability.

This pathway risks repeated military strikes, further economic devastation through escalated sanctions, and persistent regional instability.

However, nuclear weapons would provide ultimate deterrence against regime change military intervention, potentially explaining Iranian leadership attraction to this option despite massive costs.

Scenario 2

Diplomatic Resolution

International negotiation produces sustainable agreement reconciling Iranian nuclear rights with nonproliferation concerns, similar to JCPOA but with improved verification and longer-term stability frameworks.

This requires U.S.-Iranian political will that current trajectories undermine, though potential Trump administration negotiations offer limited possibility if geopolitical calculations shift.

Scenario 3

Prolonged Ambiguity

Iran maintains threshold nuclear capability—highly enriched uranium stockpiles, advanced centrifuges, scientific expertise—without formal weapons development or NPT withdrawal, creating perpetual international tension, repeated military confrontations, and economic stagnation.

This pathway aligns with current trajectory and Iran’s demonstrated preference for preserving optionality without commitments forcing irreversible decisions.

Cultural Identity Preservation

Persistent Diaspora Networks and Cultural Continuity

Despite political hostility between Iranian and American governments, the Iranian diaspora—particularly concentrated in North America, Europe, and Gulf states—maintains profound Persian cultural identity through literature, artistic production, language preservation, and community institutions.

The diaspora functions as guardian of pre-revolutionary Iranian identity while simultaneously contributing to political and social movements in host countries, creating transnational cultural networks resistant to state control.

Iranian cultural heritage encompasses poetry, calligraphy, carpet weaving, cuisine, architectural traditions, and philosophical contributions to Islamic civilization—elements transcending political regimes and maintaining continuity across millennia.

The ancient Zoroastrian tradition, preserved by diaspora Parsi communities in India for over thirteen centuries following the Islamic conquest, demonstrates capacity for cultural survival across religious and political transformation.

Iran’s cultural and civilizational identity remains decoupled from political regime.

Revolution, reform, or regime change would not fundamentally alter Persian cultural inheritance—the 2,500-year trajectory of literary production, artistic achievement, and civilizational contribution would persist regardless of political system configuration.

Cultural identity preservation represents Iran’s greatest strategic asset and most durable national characteristic, less vulnerable than political institutions to revolutionary transformation or military pressure.

Synthesis: Iran’s Prospective Future 2025-2035

Most Probable Trajectory

The most likely scenario over the next decade involves persistent authoritarian regime survival combined with gradual economic decline, regional influence erosion, and cyclical military confrontation with Israel and the United States, producing neither democratic breakthrough nor regional hegemony, but rather managed decline within constrained parameters.

This trajectory reflects several reinforcing dynamics

Regime institutional resilience

The Islamic Republic’s security apparatus possesses demonstrated capacity for sustained repression, the Guardian Council maintains ideological gatekeeping preventing genuine political pluralism, and Supreme Leader succession mechanics ensure clerical continuity absent dramatic intervention.

Historical authoritarian regimes typically prove more durable than optimistic forecasters predict.

Economic stagnation

Comprehensive international isolation, oil sector constraints, brain drain, and demographic liabilities will likely prevent genuine economic recovery regardless of sanctions status.

Iran may muddle through with modest growth years interrupted by crisis periods, but transformative development appears unlikely within the decade.

Regional recalibration

Rather than regional hegemony restoration, Iran will likely accept reduced regional role through regional power sharing with Arab Gulf states, Israel, Turkey, and potentially China.

Iraq’s government, Lebanese political restructuring, and Palestinian political fragmentation will diminish Iranian leverage, forcing strategic accommodation rather than dominance.

Nuclear program stabilization

Rather than weaponization or capitulation, Iran will likely maintain threshold capability status, preserving maximum optionality while avoiding NPT withdrawal that would trigger regime-threatening military response. This creates perpetual tension but potentially sustainable strategic equilibrium.

Constrained political evolution

Modest reforms under reformist presidents will create surface-level social liberalization (increased women’s activity visibility, entertainment expansion, business deregulation) without fundamental political democratization.

Elections will continue, but candidate vetting will ensure regime continuity.

Alternative Scenarios Meriting Consideration

Crisis-Triggered Transformation

Severity of economic collapse, combined with renewed military escalation (potential 2026-2027 Israel strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities) could trigger cascading institutional failure, elite factional violence, and security apparatus dysfunction enabling popular mobilization.

While lower probability than regime persistence, historical precedents demonstrate authoritarian regimes can collapse relatively rapidly once institutional cohesion fractures.

External Intervention and Regime Change

Major military conflict with U.S. and Israel, potentially following nuclear weapons development or regional escalation dynamics, could destroy regime military capacity and enable regime overthrow.

However, Iraq and Afghanistan historical experience demonstrates post-intervention nation-building challenges, particularly given Iran’s size, complexity, and population’s capacity for nationalist mobilization against foreign intervention regardless of internal regime opposition.

Great Power Competition and Multipolar Stability

If U.S. strategic focus shifts toward Chinese great power competition (reducing Middle East military commitment), and if Russia and China provide enhanced material support to Iran’s defense and sanctions circumvention, regional equilibrium might stabilize with U.S., Israel, and Arab Gulf states in one camp and Iran, Russia, China in opposing camp—producing persistent tension but managed escalation avoidance.

Conclusion

Cultural Continuity Amid Political Uncertainty

Despite profound contemporary challenges, Iran’s cultural and civilizational identity will almost certainly maintain continuity over the next decade regardless of political trajectories.

The 2,500-year heritage of Persian civilization represents resilience through successive empires, religions, revolutions, and external interventions.

Contemporary political configuration—Islamic Republic, monarchical restoration, or other alternatives—represents relatively superficial variation atop deeper cultural substratum.

The Islamic Republic faces genuine legitimacy erosion, economic dysfunction, and strategic vulnerability.

However, regime collapse remains uncertain within the decade, democratization faces structural barriers, and comprehensive regional isolation constrains development potential.

Most probable outcome involves managed authoritarian persistence with modest social evolution, constrained economic recovery, regional power-sharing rather than hegemony, and perpetual strategic vulnerability to external military pressure.

Yet across these grim institutional and material circumstances, the Persian cultural tradition continues through diaspora networks, artistic production, literary excellence, and civilizational memory transcending political regimes.

Whether under Islamic Republic, reformed government, or fundamentally different system, Iran’s cultural identity will persist as continuous thread through 2,500 years of transformation—representing both constraint and opportunity for Iran’s future.