Myanmar’s Historic Election: A Manufactured Legitimacy Amid Breakdown of State Authority

Executive Summary

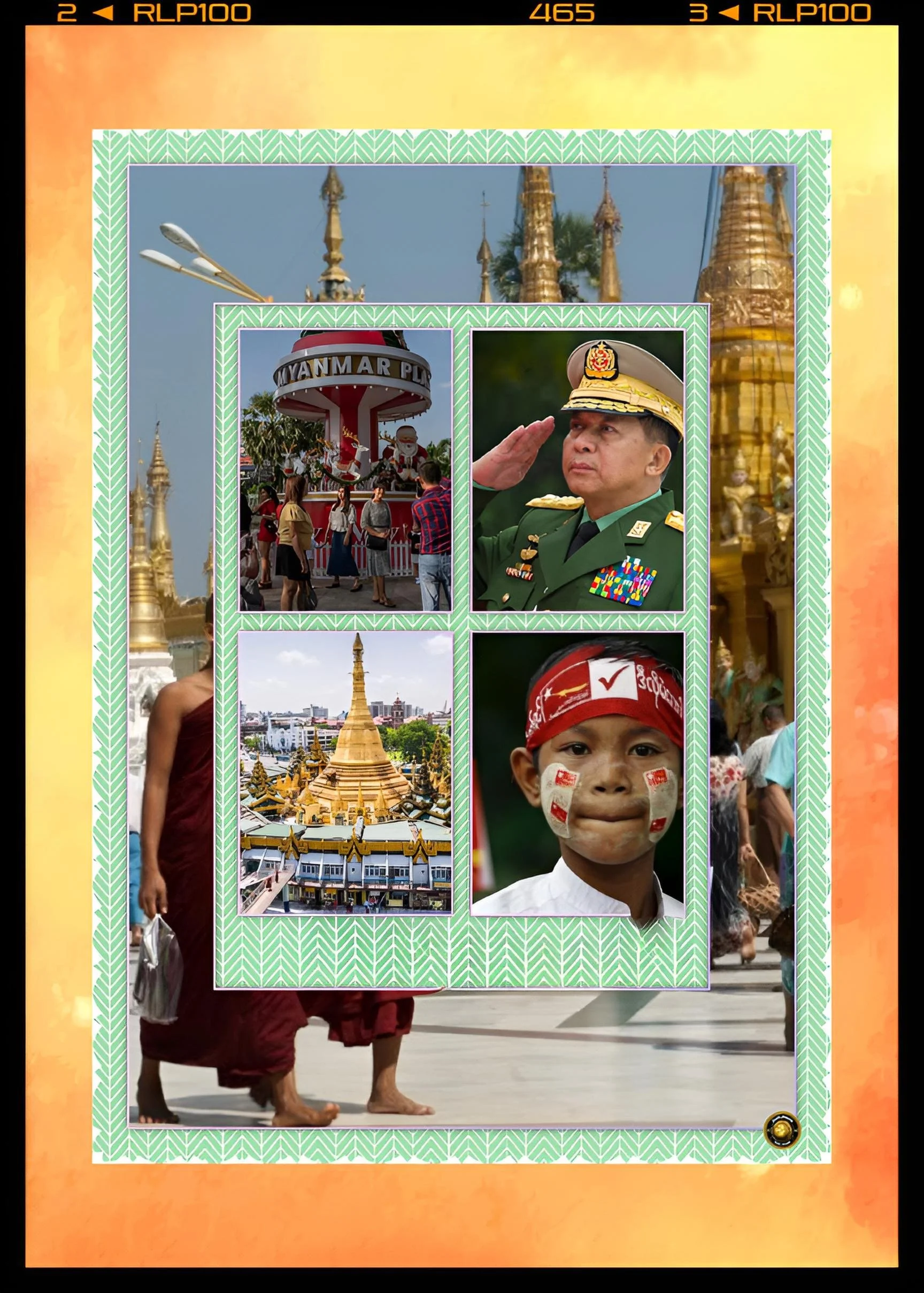

Myanmar is conducting its first general election in five years, beginning December 28, 2025, in three staggered phases across 274 of the nation’s 330 townships. This electoral exercise, orchestrated by the military junta that seized power in a coup on February 1, 2021, represents not a restoration of democracy but rather an attempt to construct a civilian veneer over sustained authoritarian military rule.

The National League for Democracy, which won 88 percent of parliamentary seats in the 2020 free and fair elections, has been forcibly dissolved and barred from participating in elections. Its leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, languishes in a 27-year prison sentence on charges widely regarded as politically motivated. In place of genuine democratic competition, voters face a landscape dominated by the Union Solidarity and Development Party. This military-aligned organization finished with a mere 11.9 percent of seats in the legitimate 2020 elections.

International observers, human rights organizations, and Western governments have unanimously condemned the 2025-26 election as neither free nor fair, occurring amid a devastating civil war in which the junta now controls only 21 percent of Myanmar’s territory. The election takes place against a backdrop of extraordinary humanitarian catastrophe: over 22,000 political detainees, more than 7,600 civilians killed by security forces, and approximately 3.6 million internally displaced persons.

The outcome is virtually predetermined—the junta seeks to secure power for Min Aung Hlaing, the 69-year-old military commander who orchestrated the coup and now rules as both chairman of the State Administration Council and prime minister. This election simultaneously reflects the international great-power competition now consuming Myanmar and exposes the profound delegitimation of state authority that the military’s own actions have precipitated.

Introduction

The question of whether Myanmar can conduct even a minimally credible election in late 2025 had been, until recently, almost academic. The military junta has controlled the electoral process entirely, dissolved or banned every major opposition party that might challenge its preferred outcome, arrested and imprisoned the nation’s most prominent democratic leader, and engineered constitutional and legal changes explicitly designed to stack the game in favor of military-affiliated parties. Yet the decision to hold elections at all, despite the junta’s secure grip on power and its repeated delays of the promised electoral timeline, signals something more complex than mere opportunism or democratic conversion.

The military seeks to transform its naked seizure of power into something resembling constitutional legitimacy, both to placate domestic constituencies exhausted by civil war and to provide strategic cover for neighboring powers—most notably China, but also India and Thailand—that provide military aid, airstrikes, and diplomatic recognition in exchange for the fig leaf of progress toward stability. In this sense, the 2025-26 election functions as a cornerstone of a larger geopolitical project: the stabilization of military rule in Southeast Asia’s most troubled nation and the prevention of any outcome that might challenge Beijing’s strategic interests in Myanmar or the broader Indo-Pacific.

The election is also, paradoxically, a confession of weakness. That the junta feels compelled to hold elections at all—rather than simply ruling indefinitely under a state of emergency—testifies to the collapse of the military’s capacity to govern legitimately.

The civil war now raging across Myanmar represents the most serious internal challenge to military authority in decades, with resistance forces and ethnic armed organizations controlling more than 60 percent of the country’s territory. In this context, the election becomes an act of desperation masked as democratic aspiration: an attempt by a weakening military elite to reclaim narrative control and shore up the minimal legitimacy needed to secure foreign military aid and prevent a terminal loss of confidence among the urban Burman population that provides the military’s cultural and political base.

History and Current Status

Myanmar’s relationship with elections and democracy has long been tumultuous, scarred by decades of military rule, insurgency, and the collision between ethnic nationalist ambitions and centralized state authority. The country languished under martial law and the army dictatorship from 1962 to 2011, when a gradual liberalization began under military leader Than Shwe.

The 2015 general elections marked a watershed: Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy won a historic landslide, capturing 258 of 330 seats in the lower house and 138 of 168 in the upper house, with international observers deeming the contest free and fair. Suu Kyi, the daughter of Myanmar’s independence hero General Aung San, had been a symbol of resistance during decades of house arrest under military rule and had won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for her commitment to nonviolent struggle. Her election promised a democratic transition in a nation where military rule had been the default setting for half a century.

That promise was short-lived. In 2020, despite the NLD’s sweeping victory—winning even more seats than in 2015—cracks in democratic institutions were already visible. Suu Kyi’s government had faced criticism for its handling of the Rohingya humanitarian crisis in Rakhine State, where military-led violence had displaced hundreds of thousands of members of a persecuted Muslim minority. She had also proven cautious on military reform and ethnic minority rights, protective of Burman ethnic dominance within a nominally federal structure, and reluctant to pursue accountability for military-era abuses. Yet the 2020 election was widely recognized as legitimate by international observers, who found no significant anomalies in the voting process. The military, despite losing decisively once again, publicly committed to accepting the results.

Then, on February 1, 2021, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing ordered the military to seize power, claiming without credible evidence that 8.6 million irregularities in voter registration had marred the 2020 election. International observers immediately rejected this claim. The military detained Suu Kyi, President Win Myint, and dozens of other NLD leaders. A state of emergency was declared, initially set to last one year, but subsequently extended through repeated six-month renewals that stretched well beyond constitutional limits.

The coup triggered immediate and widespread popular opposition. Protests erupted across major cities; security forces responded with lethal force, killing more than 600 people in the first months. The military imposed curfews, blocked internet and telecommunications, and launched a nationwide crackdown on dissent.

What the junta expected to be a brief reassertion of military dominance evolved instead into a state of civil war. Ousted lawmakers and pro-democracy activists coalesced in April 2021 to form the National Unity Government, a shadow government-in-exile that claimed to represent the legitimate voice of Myanmar. The NUG simultaneously established the People’s Defence Force, an armed wing intended to mobilize resistance against military rule. Simultaneously, Myanmar’s constellation of ethnic armed organizations—groups that had waged their own insurgencies against the Burman-dominated state for decades—increasingly allied with the anti-coup movement. By late 2023, these resistance forces had achieved a coordinated offensive that captured over 180 military outposts in Shan State and pushed junta forces back significantly. Estimates of PDF strength grew from 65,000 fighters in 2022 to approximately 100,000 by 2025, though not all were fully armed or trained. By early 2025, military control had contracted to just 21 percent of Myanmar’s territory, while resistance forces and ethnic armed organizations controlled over 60 percent.

The violence has been extraordinary. According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, an independent documentation organization, more than 22,000 people have been detained on political charges since the coup, and over 7,600 civilians have been killed by security forces. Approximately 3.6 million people have been internally displaced, driven from their homes by warfare. The economy has collapsed, the currency has devalued precipitously, and humanitarian conditions have deteriorated catastrophically. A severe earthquake in March 2025 compounded the crisis. International sanctions, imposed by the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, Australia, and others, have isolated the junta diplomatically. However, China and Russia have maintained military cooperation and provided crucial air support.

It is against this backdrop of military weakness, territorial loss, humanitarian catastrophe, and international isolation that the junta announced its intention to hold elections. The initial constitutional promise, made in 2021, was to conduct elections by February 2022. That deadline came and went. The military promised elections by August 2023, then pushed the date back indefinitely as the civil war intensified. Finally, in 2024, Min Aung Hlaing announced that a census would be conducted and elections would follow in 2025. A census did occur in October 2024. In March 2025, during a visit to Belarus, Min Aung Hlaing announced elections would be held in December 2025 or January 2026, a timeline he reaffirmed even after a devastating earthquake struck the country in March. On August 18, 2025, the military-appointed Union Election Commission formally announced the election schedule: three phases beginning December 28, 2025, with phases two and three occurring on January 11 and January 25, 2026, respectively.

Key Developments and Electoral Mechanics

The military has engineered an electoral landscape designed to ensure its victory with mathematical certainty. In January 2023, the junta enacted a new electoral law that fundamentally altered the rules of competition. Most drastically, the law switched from a first-past-the-post system, under which the NLD had consistently dominated, to a proportional representation system for the upper house. Analysts widely interpret this change as intended to dilute the voting power of concentrated opposition support, allowing the military-affiliated USDP to govern with as little as one-third of the popular vote when combined with the constitutionally reserved military seats.

Simultaneously, the law introduced onerous new registration requirements for political parties. Parties must now possess at least 100,000 members (up from 1,000), maintain at least US$35,000 in funds, and contest in at least half of all constituencies while operating offices in half of all townships. These requirements were explicitly designed to prevent smaller, ethnically-based opposition parties from participating on anything approaching equal terms.

Most consequentially, the junta enacted a new electoral law in January 2023 that mandated all existing political parties re-register under these stricter requirements. The National League for Democracy and the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy—the two parties that had won approximately 88 percent of the 2020 parliamentary seats—announced in February 2023 that they would not re-register under rules they characterized as illegitimate and undemocratic. The Union Election Commission, composed entirely of military appointees, automatically dissolved the NLD, SNLD, and 39 other parties on March 28, 2023. In a single administrative stroke, the junta eliminated every major opposition party that had demonstrated genuine electoral appeal.

The political landscape that remains is fragmented and dominated by parties with minimal track records of popular support. The USDP, which won only 26 of 330 seats in the 2020 lower house elections, is now effectively unchallenged in many constituencies. Fifty-seven parties have registered for the 2025-26 election, but most are competing only in their home regions or ethnic minority areas. Only eight parties are mounting nationwide campaigns. The parties that do participate represent narrow ethnic or regional constituencies: the Pa-O National Organisation, the Mon Unity Party, the Kachin State People’s Party, the Arakan Front Party, and several others. The combined strength of these parties in 2020 had been approximately 39 of 330 lower house seats—barely 12 percent. In 2020, parties that are now banned won approximately 276 of 330 seats (83.6 percent).

An additional layer of electoral engineering involves the constitution itself. The 2008 Constitution, drafted by the military and never submitted to a popular referendum, guarantees the military 25 percent of all parliamentary seats, appoints the military’s choice to one of the two vice presidencies, reserves key ministries for military officers, and grants the military adequate veto power over constitutional amendments. When combined with the new proportional representation system and the absence of genuine opposition parties, this constitutional guarantee virtually ensures military dominance irrespective of how voters cast their ballots.

The junta has further constrained political space through an Election Protection Law enacted in 2025, which criminalizes even mild criticism of the electoral process. Over 100 people have been arrested since July 2025 for activities as benign as distributing leaflets or posting online messages questioning the legitimacy of the elections. This legal regime is not incidental to the polls; it is central to their architecture. The junta seeks not merely to win an election, but to construct the electoral process itself as beyond legitimate contestation.

The structure of the election itself—held across three phases in 274 of 330 townships, with 65 municipalities excluded due to active conflict—further narrows the electorate. The excluded townships are precisely those where resistance forces are strongest and where the USDP would be most likely to face electoral competition. By excluding the most contested regions, the junta reduces the number of seats available for competition and concentrates voting in areas where military control is more secure.

Latest Facts and Manifestations of Contestation

Voting in the first phase occurred on December 28, 2025, in 102 townships, including the capital Naypyidaw and major cities such as Yangon and Mandalay. Early reports indicated that turnout was significantly lower than in the 2020 elections. At one polling station in Yangon’s Kyauktada township, only 524 of 1,431 registered voters (approximately 37 percent) cast ballots. Of those, 311 voted for the USDP, suggesting that opposition groups' voter boycott campaigns may have had some effect. Moreover, reported incidents of military personnel coercing voters to participate, blocking transportation to polling places, and intimidating potential voters who appeared reluctant all surfaced in early accounts.

The international response has been swift and unequivocal. The United Nations Human Rights Office characterized the election as neither free nor fair, describing it as “a theatre of the absurd.” UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk stated that there are “no conditions that permit the exercise of rights related to freedom of expression, association, or peaceful assembly,” and noted that civilians are “being coerced from all sides”—a reference to both military intimidation and threats from armed resistance groups that have warned they will target election administrators.

The International Crisis Group, a respected independent monitoring organization, issued a statement asserting that the elections are “not credible at all” because they exclude the political parties that performed well in the last two elections. Western governments have formally objected: the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Japan, Germany, and Australia have issued statements condemning the junta’s elimination of the NLD and other opposition parties and expressing no confidence in the electoral process.

Notably, India announced it would send election observers—a decision that reflects both New Delhi’s pragmatic calculation that engagement with the junta is preferable to isolation, and its fear that a complete destabilization of Myanmar would create spillover security challenges in India’s volatile northeastern frontier regions. India shares a porous border with Myanmar, and instability there directly threatens the Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland states. Thailand, similarly, has opted for cautious engagement, accepting refugees from Myanmar while maintaining functional security relationships with the junta.

China’s position has been distinctive. Beijing has provided sustained military support to the junta throughout the civil war, including airstrikes and military equipment, while declining to publicly advocate for the elections or attach conditions to its support. Chinese officials have characterized their approach as supporting stability and respecting Myanmar’s sovereignty—a framing that allows Beijing to sustain its strategic interests in Myanmar without appearing to endorse the junta’s authoritarian methods.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: Why Elections Now, and What They Reveal

The decision to hold elections, despite the junta’s secure military control and the ongoing civil war, requires explanation. Three interlocking causes drive this choice. First, the military regime faces a profound legitimacy crisis. After four years of escalating civil war, humanitarian catastrophe, and territorial loss, the junta can no longer govern effectively through the veneer of a state of emergency. The state of emergency, declared initially for one year in 2021, has been extended beyond the constitutional limit of two six-month extensions through a legal fiction that lacks legitimacy even within military-aligned circles. Holding elections, even rigged elections, allows the junta to claim a transition away from declared emergency rule toward something resembling constitutional governance. Elections create a narrative of progress, of movement toward the civilian governance that even the military publicly committed to in 2021.

Second, elections serve a critical function in managing regional geopolitics. China, India, Thailand, and other neighbors have maintained or resumed engagement with the junta partly in exchange for promises of eventual democratic restoration.

These countries—particularly China and India—have significant strategic interests in Myanmar and cannot afford its complete state collapse. Yet, they also face domestic and international pressure to appear responsive to concerns about authoritarianism and human rights. Elections, even obviously fraudulent elections, provide these powers with an exit ramp: they can claim that the junta is making progress toward democracy, that the situation is stabilizing, and that Myanmar’s trajectory toward constitutional governance justifies continued military support. China, in particular, has provided roughly 90 percent of Myanmar’s military hardware and conducted air support missions that have been crucial to the junta’s ability to maintain control of major cities.

Chinese economic interests in Myanmar—including infrastructure projects, mining concessions, and the potential use of Myanmar as a transit corridor for Chinese commerce to the Indian Ocean—depend on some minimum level of state stability. Elections enable Beijing to portray the junta as reforming and thus justify its continued military and financial support.

Third, elections represent the military elite's attempt to resolve succession questions within the officer corps. Min Aung Hlaing is now 69 years old and has led Myanmar for four years. The 2008 Constitution prevents him from assuming the presidency while remaining commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Elections create a mechanism by which he can presumably stay in power through a presidential position while ceding nominal command of the military to a loyal subordinate, or ensure his favored candidate becomes president while he retains military authority. Elections provide a constitutional mechanism for managing this succession without triggering factional conflict within the military.

The effects of holding elections in this context are multifaceted and troubling. Domestically, the elections further delegitimize state institutions. Rather than demonstrating a transition toward democracy, the rigged electoral process confirms that the junta has no intention of surrendering power or accepting genuine democratic accountability. Opposition voices that were already suppressed become even more vociferous in denouncing the elections as fraudulent.

The National Unity Government and aligned resistance forces have declared that anyone cooperating with the polls is complicit in “high treason,” creating a binary choice for many administrators and community leaders between defying the junta or being labeled traitors by resistance forces. This binary choice, in turn, deepens societal fractures and makes genuine reconciliation more distant.

Internationally, the elections provide strategic cover for China and India while simultaneously deepening the junta's isolation from Western powers. This dynamic itself becomes a geopolitical dividing line: Western nations maintain sanctions and condemn the elections. At the same time, Asian powers engage tactically with the junta and treat elections as evidence of progress. This division undermines the coherence of the international response to Myanmar’s crisis and gives the junta room to play regional powers against each other.

The elections also signal to resistance forces that armed struggle is their only viable path to power. If the regime is unwilling to accept electoral defeat—as the 2021 coup demonstrated it would not—then elections are not a mechanism for democratic change. This message encourages continued armed insurgency and makes a negotiated settlement less likely. The junta’s actions have thus created a self-fulfilling prophecy: by refusing to accept election results they dislike, they convince resistance movements that force is the only effective strategy, which, in turn, justifies the junta’s claim that it cannot risk free elections in the current security environment.

Future Steps and Geopolitical Implications

The election’s second phase is scheduled for January 11, 2026, and the third for January 25, with results expected by the end of January. The outcome is virtually inevitable: the USDP will claim a plurality or majority, depending on how votes are counted under the new proportional representation system.

Min Aung Hlaing will either become president (if he chooses to leave military command) or will orchestrate the election of a close ally to the presidency while retaining military power. In either case, the trajectory is clear: the military will convert its de facto rule into a constitutionally legitimized form of governance. The junta will claim that elections have been held, democratic processes have been restored, and Myanmar is on a path toward normalcy.

This outcome will have several downstream effects.

First, it will provide political cover for China and India to justify continued military and economic engagement with Myanmar. China has already made clear that it will recognize the results and treat them as legitimate, regardless of international condemnation. This recognition will allow Beijing to claim that Myanmar is stabilizing and that its own strategic investments and military support are bearing fruit. India, similarly, will likely adopt a pragmatic posture of engaging with the elected government while quietly noting that international attention to Myanmar has diminished.

Second, the elections will intensify the civil war rather than resolve it. The resistance movements—the NUG, the PDF, and the ethnic armed organizations—will treat the election results as confirmation that peaceful democracy is impossible under military rule and that only armed struggle offers hope. Intelligence reports already indicate that resistance forces are preparing for escalated campaigns in 2026, targeting key infrastructure, military supply lines, and administrative centers.

The Myanmar Civil War Mapping Project, which monitors territorial control in real time, indicates that resistance forces are gradually consolidating control in border regions and pursuing a long-term strategy to strangle the junta’s capacity to supply major cities.

Third, the elections risk triggering a regional security crisis if neighboring countries become more directly involved in Myanmar’s conflict.

Thailand currently hosts approximately 100,000 Myanmar refugees in camps along its border and maintains functional security relationships with both the junta and ethnic armed organizations in border areas. If the junta escalates its military campaign in regions bordering Thailand, or if refugee flows dramatically increase, Bangkok may find itself forced to choose between supporting one side or the other, with significant consequences for regional stability.

India faces similar pressures on its northeastern border, particularly in Mizoram and Manipur, where insurgent groups have traditional sanctuaries in Myanmar and cross-border military operations could spiral into a broader India-Myanmar crisis.

China’s role will be particularly consequential. Beijing has substantial investments in Myanmar and strategic interests in maintaining stability. However, China has also maintained relationships with some ethnic armed organizations and could potentially shift its support if the junta’s position became untenable.

An escalating civil war coupled with a more explicitly pro-China political outcome could also trigger American and Indian countermoves, including support for resistance forces, covert operations, or diplomatic isolation campaigns.

Fourth, the elections will accelerate Myanmar’s fracture into regional autonomous zones controlled by ethnic armed organizations and resistance forces. Already, large areas of northern Shan State, Rakhine State, and Kachin State are governed de facto by armed organizations that have little regard for central state authority.

As the junta’s control becomes more tenuous, these zones will likely solidify into semi-autonomous or autonomous territories, creating a de facto federalism that the 2020 NLD government never achieved through negotiation. This outcome would represent a profound transformation of Myanmar’s state structure, but would be achieved through conflict rather than constitutional reform.

Conclusion

Myanmar’s 2025-26 election stands as a paradoxical moment in the nation’s political trajectory. It represents, simultaneously, evidence of military strength and military weakness.

The junta’s ability to engineer an electoral outcome is undeniable—the rules have been written to ensure military-affiliated parties prevail, the most popular opposition has been dissolved, and the electoral machinery is controlled entirely by military appointees. Yet the very fact that elections are necessary, that the junta cannot simply rule indefinitely under an emergency decree, testifies to a more profound loss of legitimacy and capacity.

Myanmar’s military controls only 21 percent of the nation’s territory, faces an armed resistance movement numbering in the hundreds of thousands, and confronts a humanitarian catastrophe of its own making. In this context, elections are less an expression of democratic aspiration than an admission that military rule—unaided by democratic costume—is politically untenable.

The geopolitical implications are similarly fraught. The elections will provide strategic cover for China and India to justify continued engagement with the junta, which in turn will signal to Western powers that Myanmar is a region of secondary concern in the broader great-power competition and that the Indo-Pacific security order is being carved into spheres of influence.

China’s willingness to support the junta militarily while accepting its electoral claims signals Beijing’s confidence that Myanmar will remain within its strategic orbit regardless of the regime’s conduct. India’s pragmatism reflects a calculation that a stable Myanmar, even under military rule, is preferable to the chaos that genuine state collapse would produce.

For Myanmar’s people, the elections offer no genuine democratic choice, no mechanism for accountability, no path to justice for crimes committed since the coup. The resistance movements face an impossible situation: they have demonstrated the capacity to contest the junta militarily but lack the international recognition and support needed to defeat it decisively.

The NUG’s insistence on a return to pre-coup democratic governance, while admirable in principle, is increasingly unmoored from the reality of a fractured state in which regional armed organizations have little interest in reconstituting centralized Burman authority.

The election thus marks not a turning point toward democratic restoration but rather a hardening of Myanmar’s trajectory toward civil war, regional fragmentation, and great-power competition over the spoils of a weakening state.

The international community’s fragmented response—Western sanctions and condemnation coupled with Asian engagement and pragmatism—guarantees that Myanmar will remain a contested space. In this proxy arena, competing visions of regional order, state sovereignty, and legitimate governance will be played out through military means.

The elections themselves, whatever their immediate outcome, will change little on the ground. What matters is not the ballots cast in December 2025 and January 2026, but the military campaigns already underway in the mountain regions and the global contest for Myanmar’s strategic position in the Indo-Pacific. On those fronts, the junta’s hold on power remains increasingly precarious, its international legitimacy hollow, and the prospect of genuine democratic restoration more distant than at any point since the 2015 elections promised that Myanmar might finally escape the shadow of military rule.