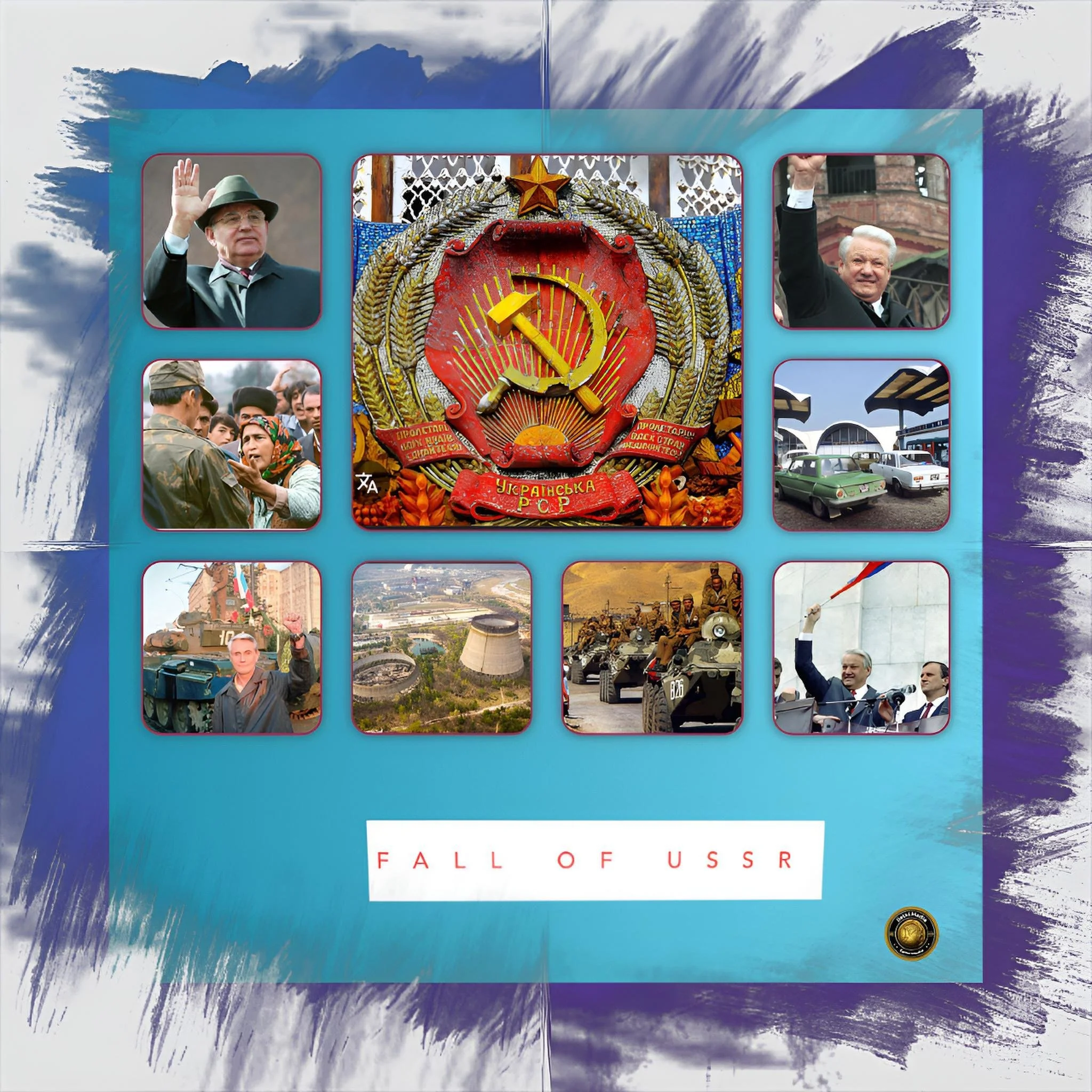

You Won’t Believe What Really Caused the USSR to Collapse—It Wasn’t What You Thought - USSR revisted -Part I

Executive Summary

The Communist Experiment Ends: Lessons from the Soviet Union’s Seventy-Year Arc

The Soviet Union, established in December 1922 as a communist federation of republics, evolved through distinct historical phases that reflected both extraordinary achievements and systemic vulnerabilities.

From its triumph as a decisive Allied power in World War II to its emergence as a technological pioneer in space exploration, the USSR presented a façade of ideological certainty and superpower status. Yet beneath this veneer, structural economic contradictions, geopolitical overreach, and failed reform efforts accumulated into a cascade of crises that culminated in the state’s dissolution on December 25, 1991.

The Soviet experience demonstrates how centralized planning, initially effective for rapid industrialization, ultimately proved incompatible with dynamic economic competition, and how reform attempts—when undertaken without ideological transformation—can precipitate rather than prevent systemic collapse.

This analysis examines the Soviet era as a coherent historical trajectory from revolutionary consolidation through superpower competition to final disintegration, with particular attention to the causal mechanisms that rendered the system unsustainable.

Introduction

When Empires Fall: Understanding the Multi-Causal Cascade Behind Soviet Collapse

The Soviet Union occupied a singular and consequential place in twentieth-century history. As the first state to attempt the wholesale implementation of Marxist communism on a continental scale, it represented both an ideological alternative to Western capitalism and a demonstration of how centralized power could mobilize resources toward state objectives.

Emerging from the ruins of Tsarist Russia following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics formally established itself on December 30, 1922, when delegations from the Russian SFSR, Ukrainian SSR, Byelorussian SSR, and Transcaucasian SFSR approved the Treaty on Creation of the USSR.

This act consolidated Bolshevik authority across the territories of the former Russian Empire and created a federal structure that, despite formal provisions allowing republics to secede, would prove remarkably durable for nearly seven decades.

The Soviet trajectory encompassed radically divergent phases of development and governance.

The era proceeded from Lenin’s pragmatic New Economic Policy of the 1920s through Stalin’s catastrophic but industrializing terror of the 1930s, his crucial role in defeating Nazi Germany on the Eastern Front, Khrushchev’s partial de-Stalinization and tentative reforms, Brezhnev’s period of apparent stability masking economic stagnation, and finally Gorbachev’s ambitious but ultimately destabilizing reform initiatives.

Each phase reflected specific historical contingencies, leadership decisions, and underlying structural dynamics. Yet the Soviet experience ultimately illustrates how authoritarian systems dependent upon centralized coercion, ideological monopoly, and command-based resource allocation face insurmountable challenges when confronted with technological change, fiscal pressures, and the diffusion of information.

Understanding the Soviet era requires examining not merely its dramatic endpoints—the purges and collectivization, the space race achievements, the Afghan quagmire, the Chernobyl catastrophe—but the interconnected economic, ideological, and geopolitical factors that rendered the system progressively less tenable across its final decades.

Key Developments: From Consolidation to Crisis

Foundational Period and the Stalin Transformation (1922–1953)

The Soviet Union emerged from ideological conviction and Marxist theory reimagined through Lenin’s organizational innovations, particularly the concept of the vanguard party concentrated in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU).

The foundational ideology, Marxism-Leninism, provided intellectual legitimacy for absolute party monopoly, explaining that the CPSU—as the enlightened representative of the working class—possessed the right and obligation to pursue policies that, however unpopular, represented objective historical necessity.

This theoretical framework enabled the justification of vast coercive apparatus, from secret police to gulag systems, as instruments of necessary class struggle.Team is

The construction of the Soviet system under Stalin transformed the USSR from a territory attempting tentative market adjustments into a totalitarian mobilization state.

Beginning in 1928, Stalin announced the “Great Turn” toward comprehensive industrialization and the forced collectivization of agriculture, abandoning the limited market mechanisms of the New Economic Policy.

The collectivization process, which compelled peasants to abandon private farms and join vast state-controlled collective farms, represented one of history’s most catastrophic instances of state-imposed suffering. The state immediately established collection quotas at deliberately unachievable levels, creating artificial famine conditions.

Between 1932 and 1933 alone, approximately three million people perished from starvation, with another six to ten million dying through execution for resistance or related deprivations.

The human cost was staggering, yet the collectivization achieved its intended economic purpose: it extracted agricultural surplus to finance the import of foreign machinery and the expansion of industrial workforce, thereby subsidizing rapid industrialization through peasant immiseration.

The Five-Year Plans, initiated in 1928, embodied Stalin’s vision of transformation through centralized command. Despite the fact that production quotas were never actually achieved and thousands died during the frenzied industrial buildup, the plans succeeded in establishing industrial parity with Western powers.

By the eve of World War II, the USSR had become the world’s third-largest industrial power, a transformation accomplished through unparalleled concentration of state authority, suppression of all autonomous economic initiative, and ruthless extraction of resources from the countryside.

The Great Purge of the late 1930s, occurring simultaneously with industrial transformation, eliminated perceived enemies of the state through execution and imprisonment, further consolidating Stalin’s absolute power and creating a society dominated by fear and propaganda.

World War II and Superpower Emergence (1941–1945)

The Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, initiated what Soviet historiography termed the Great Patriotic War and what Western historians recognize as the Eastern Front—the deadliest theater of World War II.

The conflict imposed immense human and material cost upon the Soviet Union, yet Soviet military and industrial mobilization ultimately proved decisive.

The battles of Stalingrad and Kursk represented the turning points where Soviet forces arrested German offensives and initiated the sustained push toward Berlin.

By the war’s conclusion in May 1945, the Soviet Union had emerged not merely as a victor but as a continental power controlling Eastern Europe and positioned as a co-author of the emerging international order.

The Soviet role in World War II fundamentally transformed international perceptions of communism and Soviet legitimacy. The alliance with Western democracies, though born of necessity rather than ideological affinity, demonstrated that the Soviet system could mobilize resources for collective defense.

This achievement, coupled with the USSR’s territorial acquisitions and establishment of friendly communist governments in Eastern Europe, positioned the Soviet Union as a genuine superpower.

Yet it was precisely this outcome—Soviet dominance over Eastern Europe, Soviet testing of atomic weapons in 1949, and Soviet ideological commitment to global revolutionary change—that generated the Cold War confrontation with the United States.

The Thaw and Technological Ascendancy (1953–1964)

Following Stalin’s death in March 1953, the CPSU underwent a succession crisis that ultimately brought Nikita Khrushchev to power by 1955. The Khrushchev era introduced profound rhetorical and partial practical shifts away from Stalinist coercion.

At the Twentieth Congress of the CPSU in 1956, Khrushchev delivered his famous “Secret Speech” detailing Stalin’s crimes and initiating the process of de-Stalinization. This gesture of liberalization, known as “The Thaw,” released approximately four million prisoners from the gulag system and temporarily relaxed censorship, permitting limited literary and artistic experimentation comparable to the early Soviet period.

The Khrushchev era, despite its limited and ultimately reversed political reforms, witnessed extraordinary Soviet achievements in space exploration that captured global imagination.

The successful launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957—the first artificial satellite to orbit Earth—astonished the world and demonstrated Soviet technological capability. This achievement was followed by the launch of Laika, the first animal in orbit, aboard Sputnik 2 in 1957, and most impressively, the first human spaceflight by Yuri Gagarin on April 12, 1961.

These accomplishments provided the Soviet Union with unprecedented international prestige and appeared to validate communist claims about the superiority of socialist science.

Khrushchev weaponized these achievements for propaganda purposes, arguing that Soviet technological prowess confirmed the historical inevitability of communism and demonstrated the system’s capacity for generating innovation despite capitalist competition. However, the space program’s successes obscured mounting economic and political difficulties.

Khrushchev’s attempts at economic reform—including the creation of regional Councils of People’s Economy (sovnarkhozes) designed to decentralize industrial management—generated opposition from entrenched bureaucratic interests and professional economists. His promises of reaching communism within twenty years by expanding consumer production and reducing working hours proved unrealistic, and the failure of these pledges contributed to his political isolation.

In October 1964, conservative elements of the CPSU Politburo, Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1917-1991) removed Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev from power, an outcome that would reverse the partial liberalization of the Thaw and inaugurate a period of renewed conservatism.

The Era of Stagnation (1964–1985)

The Brezhnev period, spanning from 1964 until Leonid Brezhnev’s death in November 1982, subsequently consolidated by brief tenures of Yuri Andropov (1982–1984) and Konstantin Chernenko (1984–1985), acquired the retrospective designation “Era of Stagnation.”

This label, articulated by Mikhail Gorbachev upon his ascension to power, captured the combination of economic deceleration, technological stagnation relative to Western competitors, and political rigidity characteristic of the period.

Yet the early Brezhnev years were not uniformly stagnant. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, Soviet economic growth continued, albeit at declining rates, and the Soviet Union reached the zenith of its international prestige and military-strategic parity with the United States.

The policy of détente in the early 1970s symbolized a brief moment where Cold War tensions appeared to moderate through arms control agreements and increased diplomatic engagement.

This period of apparent stability proved deceptive. The command economy, effective in mobilizing resources for state-prioritized sectors such as heavy industry and military production, proved increasingly incapable of responding to consumer demands, technological innovation, and competitive global economic change.

Growth rates declined inexorably from the 1950s onward, a phenomenon attributable to the exhaustion of extensive growth models (simply expanding labor and capital inputs) and the impossibility of intensive growth (generating productivity improvements) under conditions of centralized planning that suppressed innovation and entrepreneurial initiative.

The state’s inability to adapt rapidly to shifting global conditions, particularly the emergence of information technologies and computerized production systems in which Western economies gained decisive advantages, widened the technological and productivity gap separating the USSR from advanced capitalist economies.

The Afghanistan invasion, initiated in December 1979 as Soviet forces entered Kabul to support the Marxist Afghan government against anti-communist mujahideen insurgents, represented a critical decision point with catastrophic consequences.

The Soviets deployed approximately 100,000 troops against an estimated 150,000 guerrilla fighters equipped increasingly with American Stinger missiles and other advanced weaponry.

The conflict exacted an extraordinary toll: over 15,000 Soviet soldiers died, with another 30,000 wounded, while the Afghan civilian death toll exceeded 500,000, with millions more displaced to neighboring countries.

The war persisted for nearly a decade, consuming enormous financial and material resources and contributing substantially to the deficit spending that would accelerate Soviet economic deterioration. Beyond the direct costs, the Afghanistan adventure symbolized the overreach of Soviet power, demonstrating that military superiority could not guarantee political victory in asymmetric conflict and eroding the ideological legitimacy of socialist internationalism when confronted with manifest brutality and failure.

Crisis and Collapse (1985–1991)

Mikhail Gorbachev’s ascension to the position of General Secretary of the CPSU on March 11, 1985, at age fifty-four, initiated the period of reform that paradoxically culminated in Soviet dissolution.

Gorbachev recognized that the Soviet economy faced structural crisis: growth had stalled, technological innovation lagged Western competition, Afghanistan remained an unwinnable quagmire, and elite perception of systemic dysfunction had deepened.

His response concentrated on two interconnected reform initiatives: perestroika (restructuring) intended to revitalize the economy through partial decentralization and introduction of market mechanisms, and glasnost (openness) designed to generate transparency and permit public discussion of systemic problems.

The Chernobyl nuclear disaster of April 26, 1986, proved a pivotal moment that undermined the credibility of both reform initiatives. An explosion at reactor four of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in Ukraine released massive quantities of radioactive material across the Northern Hemisphere, necessitating the evacuation of 335,000 residents and causing immediate casualties with long-term health consequences affecting millions.

The Soviet government’s initial response—attempted concealment followed by revelation when neighboring countries detected radiation—contradicted the very transparency that glasnost was intended to introduce.

Gorbachev himself later stated that Chernobyl was “perhaps the real cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union,” a judgment that reflects the disaster’s triple impact: financial drain on already depleted state budgets, exposure of the state’s unwillingness to prioritize public safety over economic efficiency, and demonstration that Soviet technological systems could fail catastrophically despite official assurances of safety.

Gorbachev’s economic reforms, initially modest in scope, became progressively more ambitious yet simultaneously more contradictory.

The shift toward semi-market mechanisms while maintaining state ownership and subsidies of enterprises created perverse incentives: firms oriented toward meeting quotas and retaining profits rather than supplying mandated goods to other enterprises; republics began asserting control over local resources and withholding tax revenues from the center; and the disruption of centralized planning without establishment of functioning market institutions generated acute shortages and inflationary pressures.

The state responded to mounting deficits through monetary expansion, which exacerbated inflation and further eroded living standards.

Simultaneously, falling oil prices—from 30.9 billion rubles in 1984 to 20.7 billion rubles in 1988—devastated Soviet foreign exchange earnings, while Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign reduced state revenue by approximately 11.5 billion rubles annually.

The cumulative fiscal crisis, reflected in escalating budget deficits from 17–18 billion rubles in 1985 to 120 billion rubles by 1989, rendered the state effectively bankrupt.

The political consequences of economic disorder proved irreversible. Glasnost permitted media criticism of economic failure, creating public awareness of systemic crisis precisely when conditions deteriorated.

The Congress of People’s Deputies, established in 1989 through semi-free elections, introduced competitive political discourse within official structures and legitimated the existence of grievances against communist rule.

Gorbachev’s removal of the constitutional provision establishing the CPSU’s monopoly on power simultaneously opened space for political movements outside party control.

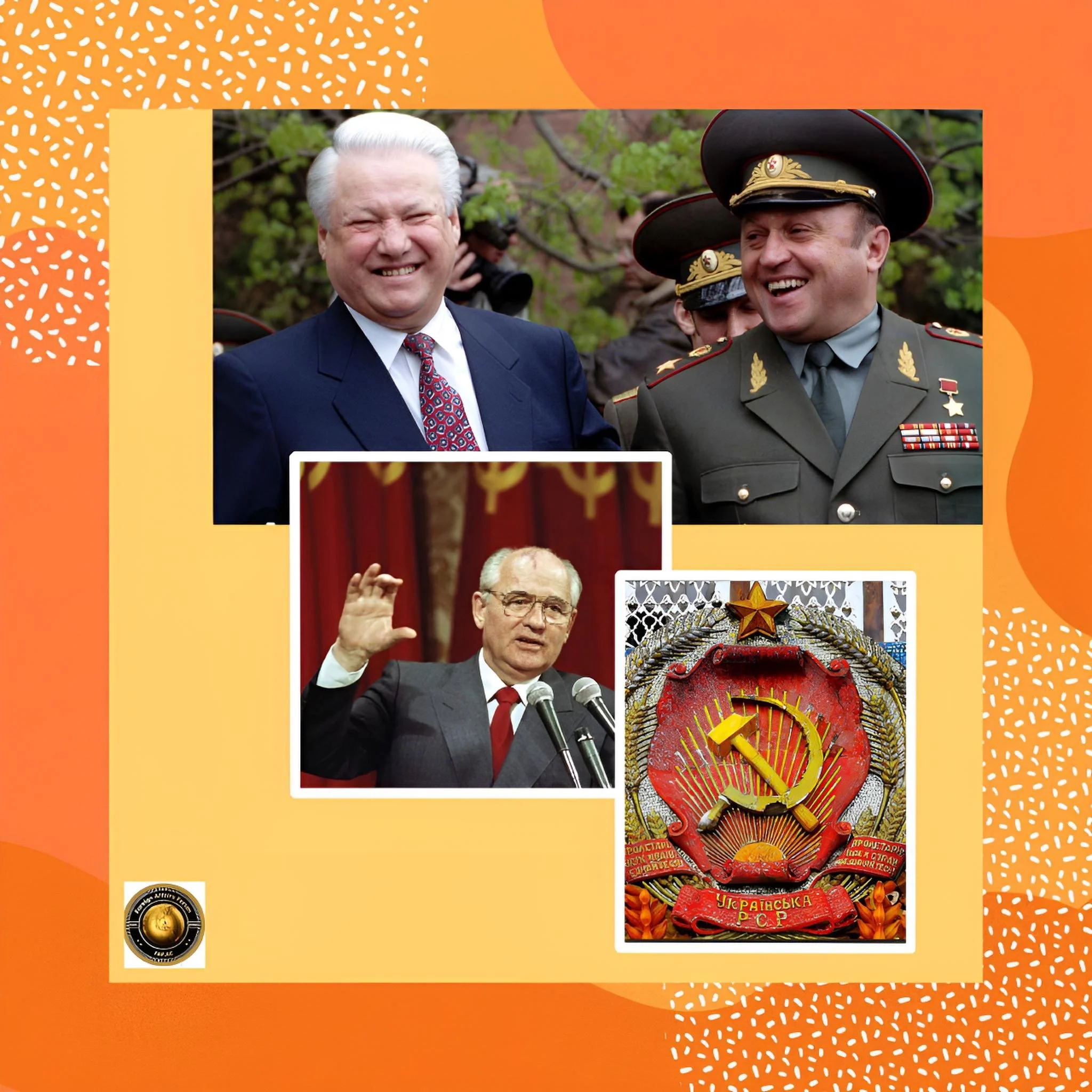

Most significantly, Boris Yeltsin’s election as President of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1991 provided an alternative power center with independent democratic legitimacy. Yeltsin capitalized on this position to demand greater Russian sovereignty, advocate radical economic transformation, and ultimately orchestrate the dissolution of the USSR.

The failed hardline coup of August 19–21, 1991, represented the final convulsion of communist power. Conservative elements within the CPSU, alarmed by the pace of reform and the prospect of complete system transformation, attempted to restore central authority through temporary suspension of Gorbachev and reimposition of orthodox communist governance.

The coup’s rapid failure—reversed within seventy-two hours by Yeltsin’s defiant leadership—destroyed whatever residual legitimacy the Communist Party possessed.

In the aftermath, the fifteen Soviet republics began declaring independence. Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia formally announced on December 8, 1991, that “the USSR as a subject of international law and a geopolitical reality ceases its existence.”

The Baltic states, which had declared independence earlier in 1990, established themselves as sovereign nations.

Gorbachev, suddenly leading a state that no longer existed, resigned on December 25, 1991, and the Soviet flag was lowered from the Kremlin to be replaced by the Russian tricolor.

The final session of the Supreme Soviet on December 26, 1991, in which the national body formally acknowledged its own dissolution, presented an ironic anticlimax: the institution that held least real power during Soviet history was the last to officially speak for the USSR.

Facts and Concerns: Ideological Foundations and Structural Vulnerabilities

The Soviet Union at 100: Examining the Rise and Fall of a Revolutionary Experiment

The Soviet system rested upon an elaborate ideological superstructure codified as Marxism-Leninism, a doctrine claiming scientific validity for communist governance.

This ideology maintained that the CPSU, as the vanguard party representing the objective interests of the working class, possessed both the right and the responsibility to exercise dictatorial power, suppressing all political alternatives and centrally directing all economic activity toward the transition toward communism.

The state professed commitment to atheism, restricting religious expression and organizing campaigns against religious belief. Yet beneath the ideological apparatus lay specific structural features that generated both the system’s apparent successes and its ultimate incapacity for sustainable development.

The command economy, characterized by centralized planning through the State Planning Committee (Gosplan), attempted to coordinate all productive activity through administrative commands rather than market prices. In theory, central planners could rationally allocate resources according to socialist principles and prioritize production of essential goods according to social need rather than profit maximization. In practice, the system generated persistent inefficiencies.

Planners, lacking adequate information about consumer preferences and technological possibilities, established production quotas that bore insufficient relation to actual demand or realistic capacity.

Enterprises, facing mandatory targets, reduced production of non-mandated items and shifted production toward higher-priced goods easiest to manufacture with existing capital, disrupting supply chains and preventing other enterprises from meeting state orders.

Consumer goods remained chronically scarce throughout the Soviet period, and technological innovation lagged Western competitors because the system provided no incentive for risk-taking or departure from established production methods.

The structural deficiency of the command economy became progressively more consequential as international competition intensified and technological advancement accelerated. Whereas in the 1950s and 1960s centralized planning could mobilize resources for dramatic achievements in heavy industry and space exploration, by the 1970s and 1980s the system’s rigidity became a decisive liability.

The computer revolution and information technologies, which generated productivity breakthroughs in Western economies, proceeded at a vastly slower pace in the USSR.

Soviet agriculture, despite periodic investment and reform, remained substantially less efficient than American agricultural production, requiring persistent grain imports and continuing subsidy. The service sector, minimal in Soviet planning, proved incapable of responding to consumer demands for adequate housing, transportation, healthcare, and retail services.

The Soviet system’s dependence upon oil and gas exports as the primary source of foreign exchange created critical vulnerability to global energy markets. Throughout the 1970s, rising energy prices supplied the Soviet government with foreign exchange enabling purchases of foreign machinery and management of external debts.

Beginning in 1980, however, oil prices declined substantially—a consequence partly of deliberate Saudi policy intended to reduce Soviet revenues—imposing severe constraints on Soviet purchasing power. This external shock, combined with the structural deficiencies of the domestic economy, created fiscal pressures that proved insurmountable.

The military burden imposed by Cold War competition consumed approximately 15 to 17 percent of Soviet GNP by the 1980s, an unsustainable proportion given sluggish economic growth.

The maintenance of 4.3 million active-duty military personnel, procurement of advanced weapons systems, development of nuclear arsenals, and support for client states in the Third World absorbed resources that might have been allocated to modernization of civilian industry or improvement of consumer living standards.

Contrary to Western arguments that American rearmament under Reagan forced Soviet military escalation and thereby precipitated economic collapse, revised CIA estimates indicate that Soviet military spending remained relatively constant throughout the 1980s.

The burden did not increase responsiveness to American military challenges; rather, military spending persisted at unsustainable levels despite economic contraction, progressively strangling civilian sectors.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: The Cascade Toward Disintegration

Post-Soviet Trajectories: Where Did Russia’s Fifteen Republics End Up After 1991?

The Soviet collapse resulted not from any single causal factor but from an interconnected cascade of structural vulnerabilities, policy failures, and historical contingencies. Understanding the mechanism of disintegration requires identifying the sequence of effects and the feedback loops that amplified initial problems into systemic crisis.

The foundational contradiction lay in the command economy’s inherent incapacity for continuous technological innovation and efficient resource allocation in an era of accelerating technological change and intensified global competition.

The system initially proved effective for rapid industrialization and mobilization of resources toward state priorities, accomplishments that generated international prestige and genuine economic advance. Yet this success depended upon factors that became progressively less available: the possibility of continuing extensive growth by expanding labor forces and capital inputs, the salience of heavy industrial production for which centralized planning proved adequate, and international isolation permitting inattention to global competitive standards.

As growth became dependent upon productivity improvements, consumer demand intensification, and technological competition with advanced capitalist economies, the system’s structural defects became increasingly consequential. The command economy that had produced Sputnik and Gagarin proved incapable of generating computer chips, software, advanced materials, or service innovations.

Simultaneously, geopolitical overreach through the Afghanistan invasion initiated a process of resource bleeding that the strained Soviet economy could ill afford. The decision to commit 100,000 troops to indefinite counterinsurgency warfare represented a miscalculation of the sort that authoritarian systems, insulated from public deliberation and congressional oversight, are prone to undertake.

The conflict drained resources, produced no tangible strategic benefit, and generated domestic opposition particularly among military families and younger generations conscripted for service. The failure to achieve military victory against an inferior but determined opponent demonstrated the limits of Soviet power and eroded ideological confidence in the system’s capacity to manage global affairs.

The combination of economic stagnation, technological gap with the West, and military overextension created the conditions for Gorbachev’s reform initiatives. Yet the particular form these reforms assumed—attempting to introduce market mechanisms and political openness while maintaining the fundamental structures of communist rule and state ownership—generated acute contradiction. Market reforms without property rights and price liberalization created chaos rather than efficiency.

Political opening without establishing stable democratic institutions and rule of law permitted expression of grievances without mechanisms for their accommodation, intensifying dissatisfaction.

Most critically, the removal of the party’s monopoly on power through glasnost and partial democratization created alternative power centers—particularly Boris Yeltsin and the Russian republic—that possessed independent democratic legitimacy and competing visions for the Soviet future.

The Chernobyl disaster of April 1986 accelerated the process of delegitimization initiated by Gorbachev’s reforms. The catastrophe demonstrated simultaneously that Soviet technology could fail catastrophically, that the state would initially lie about the failure, and that the promises of glasnost and perestroika could not ameliorate manifest dangers.

The financial consequences of Chernobyl, adding hundreds of millions of rubles to state expenditures for evacuation, decontamination, and health services, exacerbated an already critical fiscal situation. Yet the disaster’s primary impact was psychological and political: it provided concrete evidence that the system could not be reformed from within, that the gap between official claims and reality remained profound, and that the leadership lacked either the capability or the commitment to prioritize public welfare.

The fiscal crisis became acute by 1989–1991. The combination of falling oil prices, reduced alcohol tax revenues, failed economic reforms that disrupted production without establishing functioning market alternatives, and continued military expenditures created deficits reaching 120 billion rubles annually—approximately 10 to 12 percent of Soviet GNP.

The state responded by printing money, generating inflation that eroded savings and purchasing power. Republics, emboldened by glasnost and Gorbachev’s political decentralization, began withholding tax revenues from Moscow, reducing the center’s capacity to maintain essential services.

Firms, facing ambiguous authority structures and contradictory signals about future property rights, engaged in hoarding of materials and diversion of production toward speculation rather than state-mandated allocation. The centralized system, stripped of its monopoly power but denied genuine market mechanisms, simply ceased to function coherently.

The August 1991 coup attempt provided the final catalyst for dissolution. Conservative hardliners within the CPSU, perceiving the imminent end of communist rule and Soviet unity, attempted to restore central authority.

The coup’s failure within seventy-two hours, reversed by Yeltsin’s dramatic resistance, accomplished what seven decades of communist rule had prevented: it destroyed whatever residual legitimacy the party and the Soviet system possessed.

Within weeks, the fifteen republics declared independence. Yeltsin, commanding a substantial military and security force as Russian president and possessing genuine democratic legitimacy through direct election, negotiated the dissolution of the USSR and the establishment of a looser Commonwealth of Independent States.

Gorbachev, the architect of reform, found himself leading a polity that no longer existed. The Soviet Union, which had survived civil war, Nazi invasion, and Cold War confrontation, could not survive the consequences of its own attempted reformation.

Future Trajectories and Geopolitical Implications

The Soviet Legacy Persists: How 1991’s Collapse Still Shapes Global Power Dynamics

The Soviet collapse of December 1991 reverberated across the international system, fundamentally altering the geopolitical landscape and establishing trajectories whose effects persist into the contemporary era.

The immediate consequence was the emergence of the Russian Federation as the successor state, inheriting Soviet military nuclear capabilities, permanent Security Council membership, and the aspiration to great power status, yet confronting the simultaneous institutional collapse, economic contraction, and loss of geopolitical dominion that characterized the 1990s.

The transition from Soviet communism to Russian capitalism occurred under conditions of institutional chaos, capital flight, and social dislocation that generated negative economic growth rates throughout the decade and generated nostalgia for the stability, however stagnant, of the Soviet period.

The fifteen former Soviet republics, liberated from Moscow’s centralized control, embarked upon divergent trajectories reflecting their distinct historical experiences, ethnic compositions, and geopolitical proximity to either Europe or Russia.

The Baltic states—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—rapidly transitioned toward market economies and Western integration, ultimately acceding to NATO and the European Union.

Ukraine and Georgia pursued oscillating policies balancing Russian security interests against Western integration aspirations, with the consequences persisting in contemporary geopolitical tensions.

The Central Asian republics—Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan—established authoritarian independence while maintaining substantial economic and security linkages with Russia.

Belarus established itself as a quasi-independent state maintaining particularly close ties with Moscow.

The Caucasian republics of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia pursued contested territorial arrangements and regional conflicts that continue to structure contemporary politics.

The Soviet Union’s dissolution removed one pole of Cold War bipolarity, permitting what Francis Fukuyama famously characterized as “the end of history”—the presumption that liberal democracy and capitalism had achieved ideological victory and would spread globally. Yet the subsequent decades revealed the incompleteness of this prediction.

The power vacuum created by Soviet collapse generated regional instability, proliferation risks, and ultimately the emergence of Russia itself as a revisionist power seeking to restore regional dominion and challenge American hegemony.

The non-aligned space that had characterized much of the developing world during bipolar competition disappeared, compelling nations to choose alignment with the United States or other regional powers.

The post-Cold War moment of unipolar American dominance, evident in the First Gulf War and NATO expansion through the 1990s, proved temporally bounded, succeeded by resurgence of Russian assertiveness under Vladimir Putin and the emergence of China as an alternative pole of power.

The legacy of the Soviet period extended beyond geopolitics into broader questions about the viability of alternative economic and political systems. The Soviet experience demonstrated both the possibility and the ultimate failure of centralized alternatives to capitalism.

The USSR achieved genuine accomplishments in industrialization, education, military-technical capability, and space exploration that vindicated certain communist claims about the capacity of planning to mobilize resources. Yet it simultaneously demonstrated the impossibility of sustaining such systems without either relying upon capitalist markets or accepting perpetual technological backwardness, consumer deprivation, and political coercion.

The attempt to maintain both ideological purity and economic viability ultimately proved impossible; each effort to address economic inefficiency through market reforms threatened the ideological monopoly that sustained political control, while attempts to maintain political control perpetuated the economic contradictions.

Contemporary Russia’s trajectory under Putin has involved neither restoration of Soviet communism nor sustained transition toward liberal democracy. Instead, Putin’s regime represents an attempt to resurrect Russian great power status through reassertion of control over post-Soviet space, maintenance of centralized state authority over extractive industries and security apparatus, and cultivation of nationalist ideology as a substitute for discredited communist universalism.

The Ukraine invasion of 2022 reflects this orientation: an attempt to restore Russian regional hegemony in the face of post-Soviet states’ orientation toward Western institutions. The fate of the Soviet legacy thus remains contested: post-Soviet Russia has neither fully integrated into the Western-led international order nor transcended the vulnerabilities that led to the Soviet collapse.

The structural problems of centralized resource allocation remain evident in Russia’s continued dependence on energy exports, its technological lag in advanced sectors, and its demographic and economic decline relative to global competitors.

Conclusion

From Lenin to Dissolution: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Soviet System’s Structural Contradictions

The Soviet Union represented one of the defining historical experiments of the twentieth century, demonstrating both the possibility and the ultimate unsustainability of attempting to construct a comprehensive alternative to liberal capitalism through centralized state planning and communist ideology.

From its revolutionary origins through its consolidation as a superpower, the USSR achieved genuine accomplishments: the defeat of Nazi Germany, the industrialization of a previously backward agrarian territory, the advancement of space exploration and scientific achievement, and the construction of social institutions providing employment, education, and healthcare across a vast multiethnic empire. Yet these accomplishments rested upon foundational contradictions that became progressively more consequential as global economic competition intensified and technological change accelerated.

The command economy that had effectively mobilized resources for heavy industrial production proved incapable of generating consumer satisfaction, technological innovation, or sustainable growth.

The totalitarian political system that had consolidated power through coercion and indoctrination could not accommodate demands for participation without threatening its own existence.

The Soviet collapse resulted not from external military defeat—the United States never militarily conquered Soviet territory, nor did American rearmament alone force Soviet bankruptcy—but from the exhaustion of the system’s internal logic. Gorbachev’s attempt to reform communism while preserving its essential features proved impossibly contradictory.

The introduction of market mechanisms without property rights, the opening of political discourse without abandonment of party dominance, and the delegation of authority to republics while attempting to maintain central control created chaos rather than revitalization.

The accumulated effects of economic stagnation, fiscal crisis, military overextension, geopolitical failure in Afghanistan, and technological gap with the West combined with reform-induced institutional paralysis to render the system progressively more dysfunctional.

The Chernobyl catastrophe symbolized the system’s incapacity to subordinate ideological commitments and military-industrial interests to public safety and rational economic calculation.

The Soviet experience supplies enduring lessons about the limits of centralized planning, the necessity of institutional adaptation to technological change, the capacity of reform initiated from above to generate uncontrollable consequences, and the ultimate indispensability of political legitimacy rooted in either democratic participation or continued economic performance.

The post-Soviet world has not resolved the underlying questions that Soviet collapse raised: how nations achieve technological competitiveness without capitalist market mechanisms, how states balance geopolitical ambitions against fiscal constraints, and how authoritarian systems adapt to changing circumstances without precipitating their own dissolution.

The contemporary international order reflects not a triumph of liberal democracy over communism but rather a provisional settlement in which the former Soviet superpower has been relegated to regional power status while China represents the possibility of alternative development trajectories maintaining authoritarian political control while achieving technological advancement through selective market integration.

The Soviet era thus closes not with a definitive historical verdict but with ongoing contestation over its meaning and legacy.