Sudan’s Crisis: El-Fasher, Conflict Dynamics, and Peace Prospects

Introduction

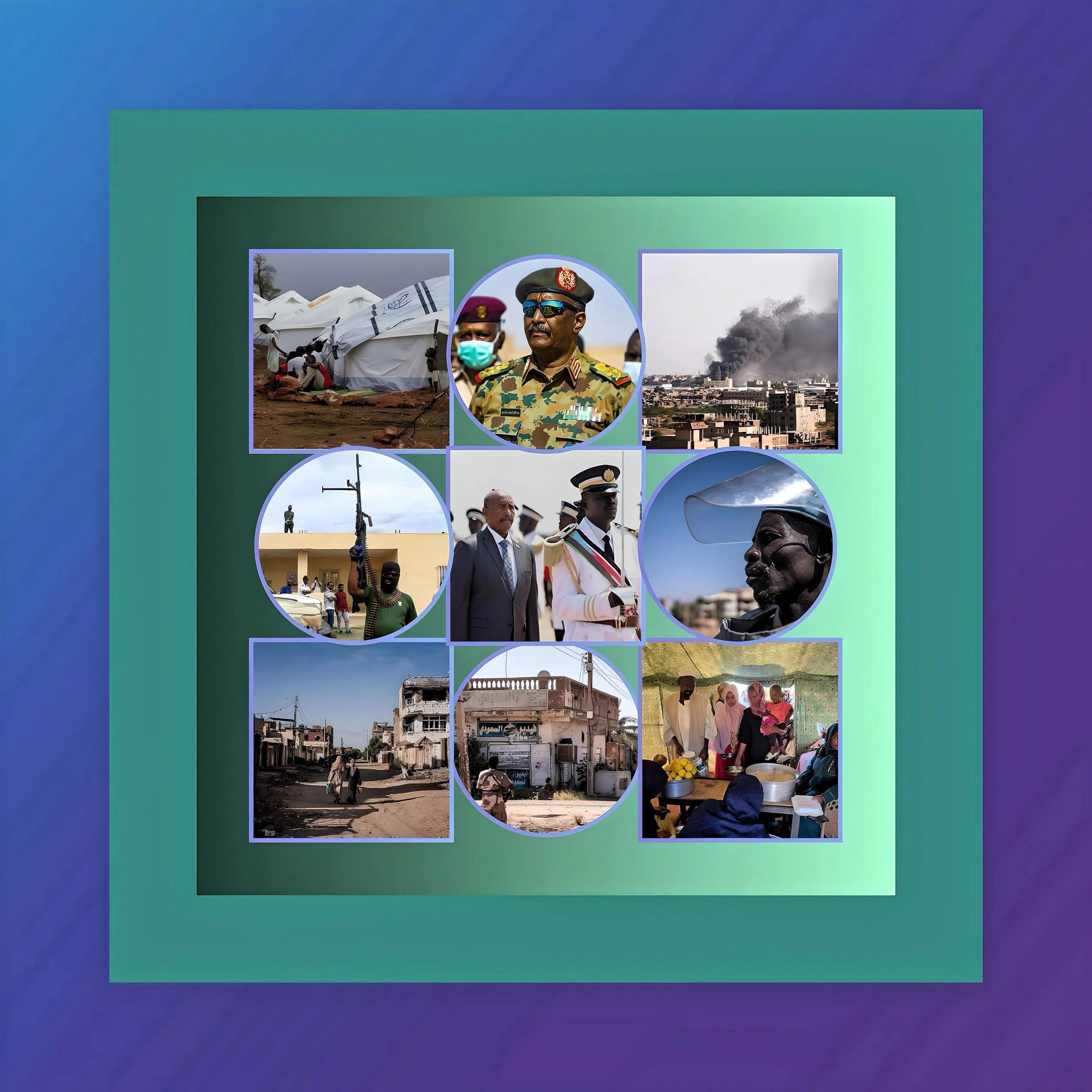

Current Crisis in El-Fasher: Ongoing Massacre and Humanitarian Catastrophe

El-Fasher, the capital of North Darfur State, represents one of the most severe humanitarian crises unfolding in contemporary conflict zones.

Following the Rapid Support Forces’ (RSF) capture on October 26, 2025, after an 18-month siege, evidence indicates an active massacre with tens of thousands of casualties.

The atrocities documented include

Scale of Violence

Satellite imagery analyzed by Yale University’s Humanitarian Research Lab reveals visible blood stains and bodies from space.

Eyewitness accounts describe scenes of mass executions, with credible reports indicating over 2,500 civilians murdered since October 26, with estimates suggesting tens of thousands may have perished in the initial days following the RSF’s takeover.

One survivor, Mutaz Mohamed Musa, described being forced to witness RSF fighters executing individuals, with fighters ordering men to run before shooting them.

Pattern of Atrocities

The violence encompasses systematic killings, sexual violence against women and girls, extrajudicial executions at medical facilities (including 460 deaths reported at Saudi Maternity Hospital alone), displacement through mass exodus, and ethnic cleansing targeting non-Arab communities, particularly the Fur and Zaghawa peoples.

Amnesty International documented that the RSF has a documented history of ethnically targeted attacks against Masalit and other non-Arab communities.

Humanitarian Crisis

The UN confirmed famine conditions in El-Fasher, marking only the second famine declaration globally in 2025 (the first being Gaza).

Over 120,000 individuals remained trapped in the city during the siege, with approximately 70,000 fleeing since the RSF takeover; notably, the absence of adult males among survivors suggests systematic targeting.

Peace Requirements and Obstacles

Achieving sustainable peace in Sudan requires addressing multiple structural and political barriers

Essential Conditions for Peace

Humanitarian Access and Ceasefire Framework

The US-led Quad coalition (comprising the United States, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and UAE) proposed a three-month humanitarian ceasefire to enable aid delivery, followed by a permanent ceasefire and nine-month transition toward civilian governance.

The RSF conditionally accepted this proposal on November 6, 2025, though the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) have shown reluctance and military skepticism.

Institutional and Governance Reforms

Any durable peace settlement must establish:

Civilian-led governance structures excluding both military and paramilitary factions from post-war administration.

Transitional justice mechanisms holding individual perpetrators accountable for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Disarmament and integration protocols for armed forces and militias.

Protection for internally displaced persons and refugees with conditions enabling voluntary return without ethnic preference.

Scholarly Analysis of Peace Obstacles

Research on Sudan’s historical peace processes reveals five fundamental barriers that persist in the current conflict:

Mutual Distrust and Bad Faith Negotiations

The government and warring factions approach negotiations with “acute suspicion and loathing,” undermining confidence-building measures.

This distrust stems from repeated ceasefire violations—the SAF violated the 2003 and 2004 ceasefire agreements, never disarmed the Janjaweed militia, and continued attacking civilians, leading rebel movements to demand international guarantees that were never fulfilled.

Absence of Political Commitment

The SAF leadership has historically lacked genuine commitment to negotiated settlements, believing that military superiority provides superior bargaining power and fearing that accommodating rebel demands in Darfur would encourage similar uprisings in marginalized regions.

The government’s immediate removal of Governor Ibrahim Suleiman when he attempted negotiating with rebels exemplified this refusal to engage politically.

Mediation Incompetence and Process Weakness

Early mediation efforts, particularly by Chad under President Déby, lacked impartiality and experience, skewing negotiations in favor of the government.

Additionally, deadline-driven diplomacy (“deadline diplomacy”) pressured rebel leaders defensively into positions they didn’t endorse, undermining their ownership of the peace process.

Critically, mediators were unable to guarantee implementation of peace agreements, rendering international guarantees meaningless to rebel groups.

Fragmentation and Leadership Divisions

Rebel movements remained fractured across competing organizations with divergent interests, while the current RSF-SAF conflict represents an unprecedented configuration: a state-created paramilitary force fighting its creator state, rather than traditional insurgent-versus-government dynamics.

The RSF’s origins in the Janjaweed militia—responsible for 2003-2005 genocidal violence—create historical trauma and legitimate fears among non-Arab populations.

Structural Power-Sharing Failures

Previous agreements like the 2006 Darfur Peace Agreement failed to address foundational issues regarding power distribution, resource allocation, and security arrangements.

Without resolving which factions control security apparatus, military integration processes, and regional governance, superficial ceasefires collapse under the weight of unresolved tensions.

External Complicating Factors

The conflict’s continuation is sustained by substantial foreign military support.

The UAE provides significant logistical and military backing to the RSF, while Egypt, Russia, and Iran provide extensive support to the SAF through drone capabilities, military consultations, and intelligence support.

This external intervention transforms a civil conflict into a proxy war where international interests supersede Sudanese civilian needs.

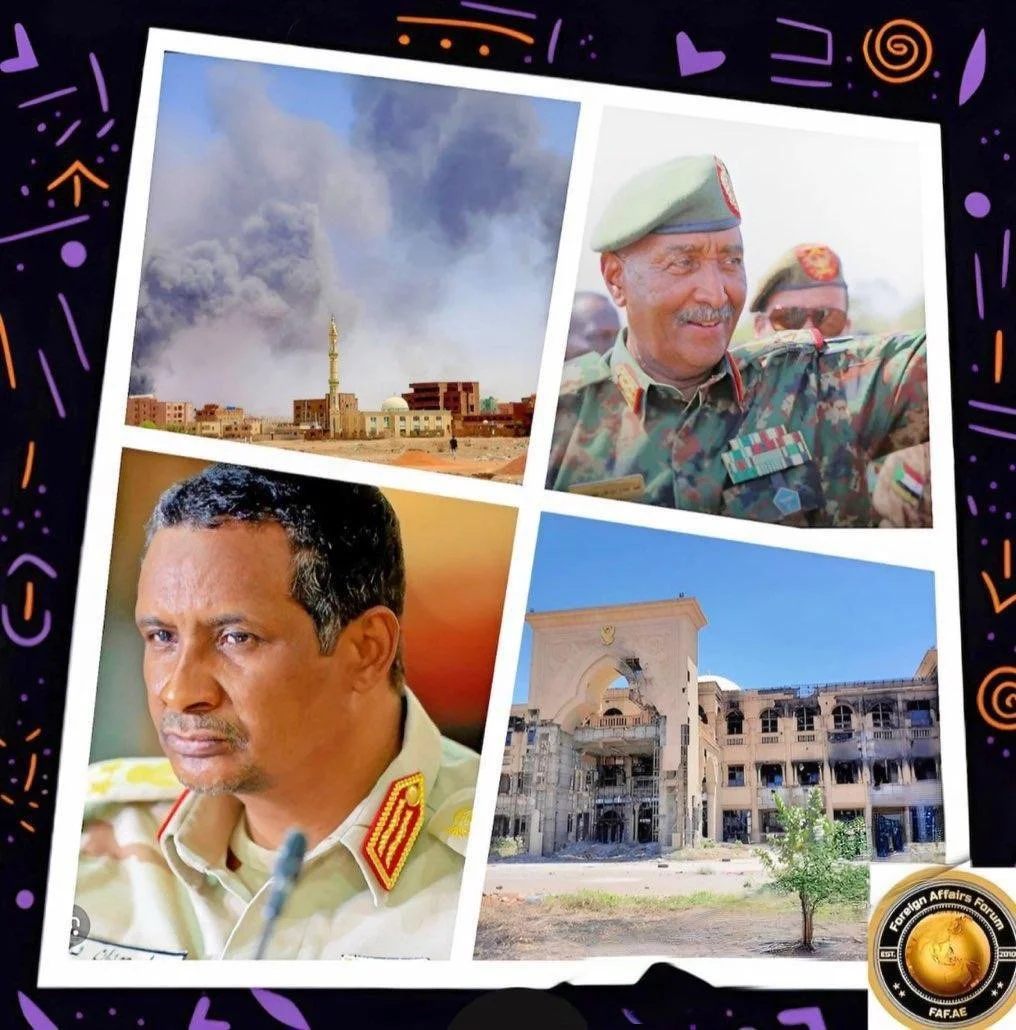

Primary Responsibility: Shared but Asymmetric

Legal and Factual Determinations:

The United States Secretary of State determined in January 2025 that members of the RSF and allied militias have committed genocide in Sudan.

Both the RSF and SAF bear responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity, yet the RSF bears primary responsibility for recent atrocities, particularly in Darfur.

The RSF has been credibly documented conducting systematic ethnic cleansing of non-Arab communities through displacement and targeted execution.

Satellite evidence and eyewitness testimony establish RSF culpability in mass executions post-October 26, 2025.

RSF leadership, particularly Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti), has been individually sanctioned by the US for orchestrating these atrocities despite acknowledging “violations” occurred.

However, the SAF also bears substantial responsibility

The SAF has conducted aerial bombardments and artillery strikes on civilian areas, obstructed humanitarian aid delivery, and continues military operations despite catastrophic civilian costs.

The distinction is that the RSF has engaged in systematic, ethnically-targeted genocide, while the SAF’s violations, though severe, are primarily collateral consequences of military operations rather than the explicit objective.

The Fundamental Impediment

Neither faction possesses legitimacy to govern post-war Sudan.

Both orchestrated a 2021 coup overthrowing the democratic civilian government, initiated war in 2023 for power consolidation, and have demonstrated through their conduct that military solutions remain their preference over genuine peace.

Their recent “humanitarian ceasefire” acceptance by the RSF appears tactically motivated by international pressure following documented atrocities rather than representing genuine commitment to peace.

Conclusion

Sustainable peace in Darfur requires international enforcement mechanisms guaranteeing implementation, displacement of both RSF and SAF from governance authority toward civilian leadership, individual accountability for perpetrators, and cessation of external military support.

Without these structural changes, ceasefire proposals will perpetuate the pattern of previous failures documented across Sudan’s conflict history.