Sudan’s Intractable War: Roots, Regional Implications, and Elusive Pathways to Peace

Introduction

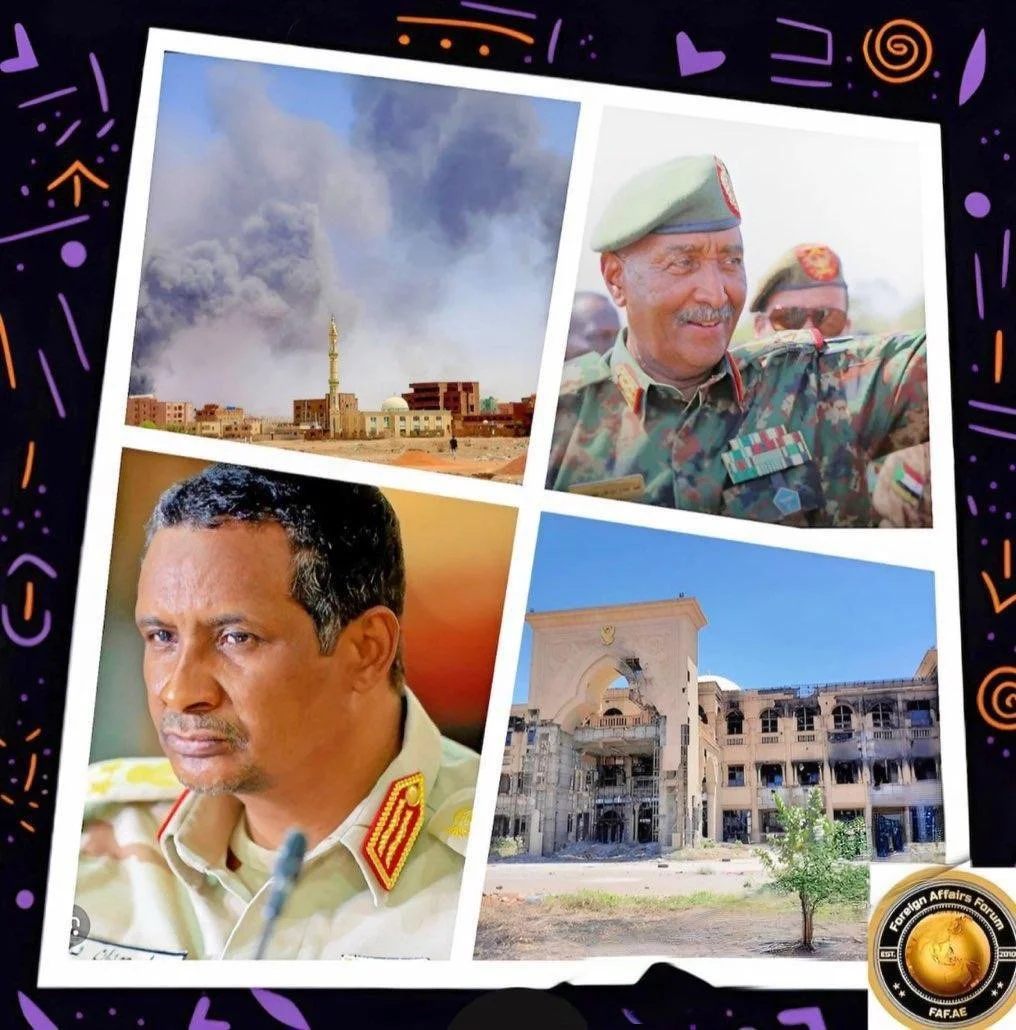

The conflict between Sudan’s Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), now in its third year, has spiraled into the largest humanitarian crisis in recorded history, displacing over 10 million people and pushing 25 million into acute food insecurity.

FAF, Africa.Media analyzes despite nations catastrophic scale, the war remains overshadowed by other global conflicts, even as external stakeholders exploit Sudan’s chaos for strategic gain

In a recent Foreign Affairs essay, political scientist Mai Hassan and humanitarian expert Ahmed Kodouda argue that the war’s intractability stems from structural governance failures, competition over resources, and escalating foreign interference.

Their analysis reveals why Sudan’s crisis defies easy resolution and threatens to destabilize the Horn of Africa.

Historical Roots of the Conflict

From Authoritarian Rule to Fractured Transition

Sudan’s current crisis is rooted in the legacy of Omar al-Bashir’s 30-year dictatorship, which relied on a dual military structure: the SAF and the Janjaweed militias (later institutionalized as the RSF).

This system allowed Bashir to balance power but sowed the seeds of conflict. After Bashir’s 2019 ouster, a fragile power-sharing agreement between the SAF and civilian groups collapsed in 2021, when General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan (SAF) and General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo “Hemedti” (RSF) staged a joint coup.

Key Fault Lines

Resource Control

The RSF monopolizes Sudan’s gold mines (40% of GDP), while the SAF dominates agricultural corridors and Port Sudan.

Ethnic Marginalization

The RSF draws fighters from Arab tribes in Darfur and Kordofan, exacerbating historic tensions with non-Arab communities.

Institutional Rivalry

The SAF views itself as Sudan’s legitimate guardian, while the RSF seeks formal political power.

Humanitarian Catastrophe and Regional Spillover

Scale of Suffering

Displacement

8.6 million internally displaced, 2 million refugees in Chad, South Sudan, and Ethiopia.

Famine

4.9 million face emergency-level hunger, with 90% of hospitals nonfunctional.

Atrocities

RSF accused of ethnic cleansing in Darfur, mirroring 2003–2008 genocide.

Cross-Border Instability

Chad

600,000 refugees strain resources; RSF cross-border raids threaten eastern Chad.

South Sudan

Over 500,000 returnees destabilize oil-rich regions.

Red Sea Security

Houthi and Somali pirate activity increases amid disrupted maritime patrols.

Geopolitical Entanglements

Proxy War Dynamics

External actors fuel the conflict to secure resources and strategic advantage

The UAE’s $2 billion annual support to the RSF, channeled through Libya and Chad, enables Hemedti’s forces to import drones and artillery.

Meanwhile, Egypt provides the SAF with intelligence and MiG-29s via its airbase in Wadi Seidna.

Structural Barriers to Resolution

Fragmented Sovereignty

Sudan has effectively bifurcated

RSF Control

Darfur, Khartoum, and key trade routes to Libya.

SAF Control

Eastern Sudan, Port Sudan, and parts of the Nile Valley.

This division creates competing governance systems, with the RSF levying informal taxes and the SAF clinging to international recognition.

Economic Incentives for War

Gold Smuggling

RSF exports $4 billion annually via UAE, funding its war machine.

Land Grabs

SAF-aligned elites seize fertile land in Gezira for export crops.

Weapons Trade

Both sides profit from arms sales to Ethiopian militias and Libyan factions.

Pathways to Peace

Challenges and Proposals

Local Peacebuilding Efforts

Kodouda highlights grassroots initiatives, such as the Nafeer mutual aid networks in Darfur, which provide cross-ethnic humanitarian relief.

However, these efforts lack scaling capacity amid systematic targeting by militants.

International Diplomacy

Hassan critiques the failure of U.S.-brokered Jeddah talks, which prioritized ceasefire pledges over power-sharing. She advocates for:

Coercive Measures

Sanctions on UAE and Egyptian entities fueling the conflict.

Civilian-Led Transition

A parallel government excluding SAF and RSF, modeled after Sudan’s 2019 revolution.

Resource Transparency

UN audits of Sudan’s gold and agricultural exports.

Role of Regional Organizations

The African Union’s (AU) 2024 suspension of Sudan has proven counterproductive. Kodouda proposes repurposing the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) to mediate, leveraging Kenya’s and South Sudan’s neutrality.

Conclusion

A Crisis at the Crossroads

Sudan’s war exemplifies how resource predation, ethnic fragmentation, and geopolitical rivalries can render conflicts self-perpetuating.

As Hassan and Kodouda emphasize, there are no quick fixes. The SAF and RSF have militarized the economy, creating a war economy that benefits elites while devastating civilians.

Breaking this cycle requires dismantling external funding streams and empowering Sudan’s civil society—the same groups that toppled Bashir in 2019.

Without such interventions, Sudan risks becoming a failed state, destabilizing a region already grappling with climate shocks and authoritarian resurgence.

The international community’s choice is stark: act decisively to halt the carnage or contend with a decades-long crisis that will echo far beyond Sudan’s borders.

Citations

Foreign Affairs, “Sudan’s Unseen War,” Hassan & Kodouda, 2025.

UN OCHA Sudan Humanitarian Response Plan, 2025.

Global Witness, “Blood Gold and the RSF,” March 2025.

IGAD Emergency Summit Proceedings, April 2025.