America’s Scramble for Rare Earth Minerals: A Strategic Analysis

Introduction

The United States is indeed engaged in an intense global campaign to secure rare earth elements (REEs), forging partnerships from Africa to Australia and Ukraine.

This scramble reflects a profound strategic vulnerability: China controls approximately 70% of global rare earth mining and a staggering 90% of processing capacity, giving Beijing extraordinary leverage over technologies essential to everything from smartphones to stealth fighters.

The irony is acute—while China holds only 44% of the world’s rare earth reserves, it has transformed this into near-total supply chain dominance through decades of strategic industrial policy.

What Are Rare Earth Elements and Why Do They Matter?

Rare earth elements comprise a group of 17 metallic elements—including the 15 lanthanides, as well as scandium and yttrium—that possess unique magnetic, luminescent, and electrochemical properties.

Despite their name, these elements are not particularly rare in nature; instead, they are seldom found in concentrated, economically extractable deposits, making mining and processing both technically challenging and environmentally destructive.

Their strategic importance cannot be overstated. REEs are essential components in over 200 high-tech applications.

A single F-35 fighter jet requires 920 pounds of rare earths.

Electric vehicle motors depend on neodymium and dysprosium magnets for efficiency.

Wind turbines, computer chips, precision-guided munitions, night vision equipment, and radar systems all rely on these critical materials.

The Department of War designated REEs as essential to national security, recognizing that without them, advanced weapons systems would be unable to function.

China’s Stranglehold: How Beijing Achieved Dominance

China’s control over the rare earth supply chain did not emerge by accident—it resulted from deliberate, multi-decade strategic planning that began in the 1990s.

As Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping famously declared in 1992: “The Middle East has oil, and China has rare earths”.

This prescient observation guided decades of state-directed investment, industrial policy, and strategic positioning

How China built its monopoly

Aggressive State Investment

Beginning in the 1990s, Beijing invested substantial state capital in processing facilities across Inner Mongolia (specifically in Baotou) and Jiangxi provinces, initially operating at a loss to build technical expertise and achieve economies of scale.

Environmental Arbitrage

China tolerated severe environmental degradation that Western nations refused to accept.

The world’s largest rare earth mine, located at Bayan Obo in Inner Mongolia, has produced over 70,000 tons of radioactive thorium waste, which is stored in leaking tailings ponds.

For every ton of rare earths produced, approximately 2,000 tons of toxic waste are generated, including radioactive residues, heavy metals, and acidic wastewater.

Western countries with stricter environmental regulations largely abandoned rare earth mining by the 1990s, ceding the field to China.

Market Flooding Strategy

Chinese producers repeatedly flooded global markets with cheap rare earths, driving prices so low that competitors in the United States, Australia, and elsewhere went bankrupt.

This eliminated competition and consolidated China’s market position.

Value Chain Integration

Rather than merely exporting raw materials, China invested heavily in midstream processing and downstream manufacturing—the higher-value portions of the supply chain.

Today, China controls 90% of rare earth refining and 93% of permanent magnet production, far exceeding its 70% share of mining.

By 2024, China was producing 270,000 metric tons of rare earths annually—77% of global production—while the United States managed just 45,000 tons (13%).

More critically, the U.S. has only one operational refining facility producing minimal quantities, while China’s refining capacity grew by 5% in 2024 alone.

Why Rare Earths Are Scarce: Geological and Processing Challenges

The scarcity problem is not geological but economic and technical.

The world has substantial rare earth reserves—approximately 100 million metric tons globally.

However, extracting and processing these minerals presents formidable challenges.

Complex Separation Processes

REEs occur as trace impurities closely bound with chemically similar elements.

Separating a single ton of usable rare earths requires extracting massive quantities of ore—sometimes necessitating processing that consumes 9-13 times the energy of initial extraction.

This makes rare earth refining extraordinarily energy-intensive and expensive.

Environmental Toxicity

Both primary mining methods—chemical leaching ponds and in-situ chemical injection—release hazardous materials into the environment.

Mining produces approximately 13 kilograms of dust, 9,600-12,000 cubic meters of waste gas, 75 cubic meters of wastewater, and one ton of radioactive residue per ton of rare earths.

Rare earth ores frequently contain radioactive thorium and uranium, posing severe health risks to nearby communities.

Regulatory and Permitting Barriers

In the United States, the average time to develop a new mine is 29 years—the world’s second longest.

Permitting and licensing smelting facilities takes 7-10 years.

These extended timelines, combined with strict environmental regulations and NIMBY opposition, have made it nearly impossible to scale domestic production rapidly.

Economic Unviability

China’s willingness to accept environmental damage, provide state subsidies, and operate on thin margins has created a cost structure that few Western competitors can match.

The world’s lowest-cost producers can make rare earth oxide for $11 per kilogram or less—mostly Chinese operations exploiting cheap labor, loose regulations, and economies of scale.

America’s Global Scramble: Deals and Desperation

Recognizing the strategic peril of near-total dependence on China, the United States has embarked on an aggressive global campaign to diversify rare earth supply chains:

Australia Partnership ($8.5 Billion)

In October 2025, the U.S. and Australia signed a landmark critical minerals agreement committing $3 billion in joint investments over six months, with an eventual $8.5 billion pipeline.

Australia holds 5.7 million metric tons of rare earth reserves (5.7% of the global total) and possesses robust mining infrastructure.

However, like the U.S., Australia lacks significant processing capacity and currently depends on China to refine much of its mined ore.

Ukraine Deal

In April 2025, the U.S. and Ukraine signed an agreement to jointly develop Ukraine’s mineral wealth, including rare earths, lithium, cobalt, and graphite.

Structured as an equal partnership with a 50-50 revenue split from new projects, the deal aims to fund Ukraine’s reconstruction while securing Western access to critical minerals.

However, any significant production remains years away—Ukraine currently mines virtually no rare earths and faces the obvious challenge of ongoing conflict.

Additionally, approximately $13.5 trillion worth of rare earth minerals are located in Russian-controlled territory, including the Donetsk and Luhansk (Donbas region), Zaporizhzhia, Crimea & Kherson, and Dnipropetrovsk regions.

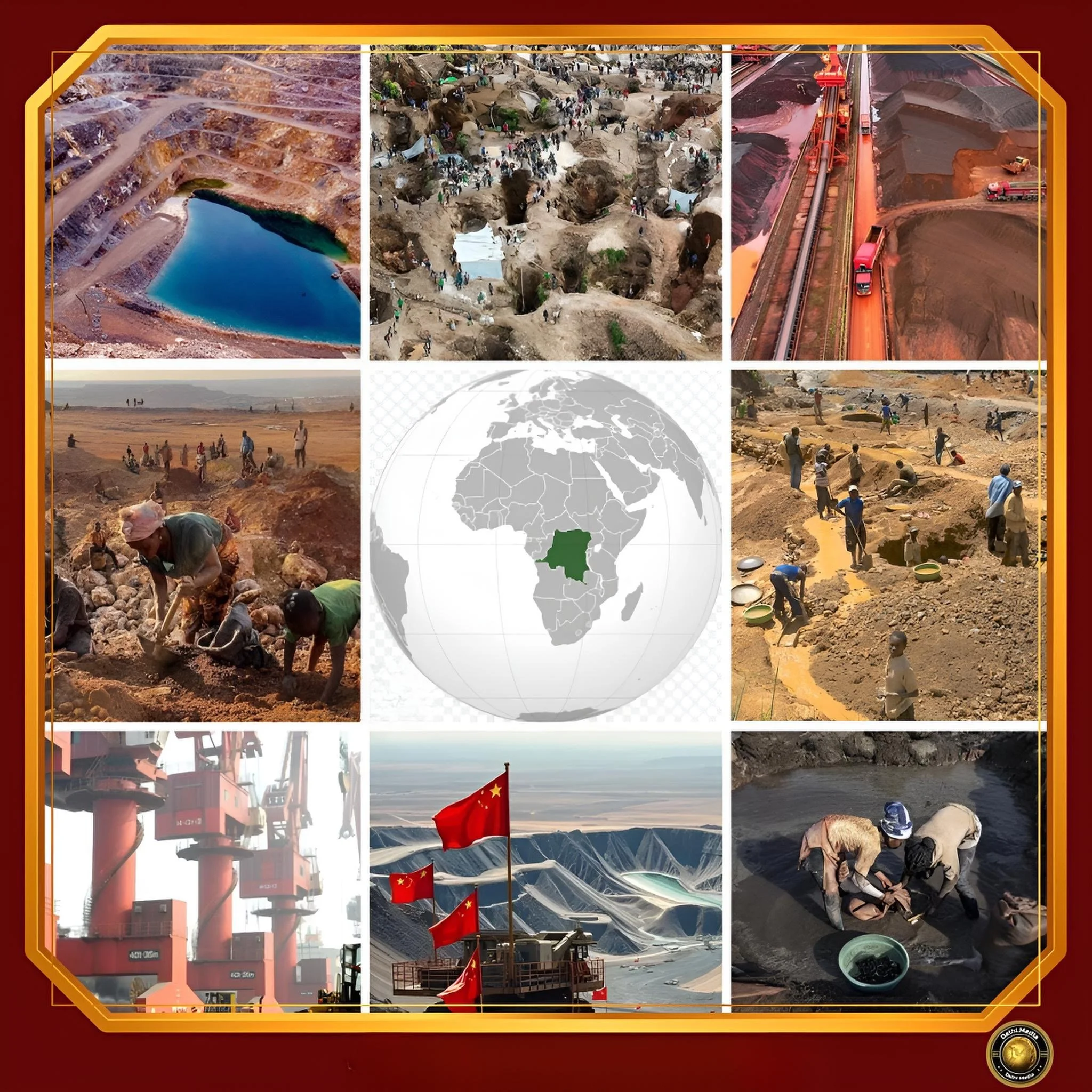

Africa Initiatives

The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) has approved multiple African rare earth projects, including a $3.4 million grant for Angola’s Longonjo project, $50 million equity investment in South Africa’s Phalaborwa project, and financing for Malawi’s Songwe Hill mine.

Africa could potentially supply 9-10% of global rare earth production by 2029-2030.

However, these projects face infrastructure deficits, political instability, and competition from Chinese investment, which already controls an estimated 97% of lithium mining projects in Africa.

Domestic Investment

The Trump administration has invested in U.S. companies, such as MP Materials (Mountain Pass mine, California), by granting it a $12.2 million tax credit and securing offtake agreements.

However, MP Materials currently ships much of its ore to China for processing due to a lack of domestic refining capacity.

The U.S. allocated $450 million in Defense Production Act funding to jumpstart rare earth magnet production, but building sufficient refining capacity is estimated to take 10-15 years.

The 155% Tariff Threat: Economic Warfare or Negotiating Leverage?

President Trump has threatened to impose a 155% tariff on Chinese goods starting November 1, 2025, unless Beijing reaches a trade deal addressing several demands: halting rare earth export restrictions, cracking down on fentanyl trafficking, purchasing U.S. soybeans, curbing Russian oil purchases, and addressing the trade deficit.

This threat comes on top of the existing 55% tariffs already in place, creating a potential cumulative rate that would effectively shut China out of U.S. markets.

Trump has also warned of an additional 100% tariff, specifically if China implements its new rare earth export controls, scheduled to take effect on December 1, 2025.

China’s Rare Earth Restrictions

In October 2025, Beijing announced sweeping export controls requiring foreign companies to obtain Chinese government approval to export any product containing even trace amounts (0.1% or more) of rare earths sourced from or processed in China.

Given China’s 90% control of processing, this effectively grants Beijing oversight of global technology supply chains. U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent called this a “bazooka at the industrial foundation of the entire free world”.

Why Would China Deal with the U.S. Despite Tariffs?

This question cuts to the heart of the strategic paradox.

Why would China cooperate with a United States threatening massive tariffs and sanctions?

The answer lies in understanding the limits of leverage, the costs of escalation, and Beijing’s long-term strategic calculus.

Economic Interdependence Cuts Both Ways: While the U.S. depends on Chinese rare earths, China relies on American markets, technology, and financial systems.

A total breakdown in trade would inflict severe economic pain on both nations.

China’s economy already faces structural challenges—slowing growth, property sector crisis, youth unemployment—making a catastrophic trade war potentially destabilizing for the Chinese Communist Party.

Risk of Accelerating Diversification

Prolonged or draconian export restrictions risk permanently driving customers away from Chinese supply chains.

Already, China’s rare earth restrictions are galvanizing unprecedented Western investment in alternative sources, including Australia, Africa, Brazil, and India.

As one expert noted, “strategic coercion through supply chain management rarely produces lasting benefits”.

If China pushes too hard, it risks losing the market dominance it spent decades building.

Negotiating Leverage, Not Permanent Ban

Many analysts interpret China’s rare earth restrictions as a tactical move to leverage upcoming negotiations between Trump and Xi Jinping, rather than a permanent cutoff.

In June 2025, a trade framework agreement eased some export restrictions, though licensing requirements remained in place.

This pattern suggests Beijing uses rare earths as a bargaining chip to extract concessions, then partially relents to avoid pushing Western nations into permanent supply chain realignment.

Diplomatic Pragmatism

Despite the threatening rhetoric, both Trump and Chinese officials have signaled a willingness to engage in negotiations.

Trump stated he wants to “assist China, not harm it,” and Treasury Secretary Bessent proposed a pause on additional tariffs if Beijing retracts the rare earth announcement.

The anticipated Trump-Xi meeting represents an opportunity to de-escalate before the November 1 deadline.

U.S. Alternative Leverage

The United States possesses counter-leverage—export controls on advanced semiconductors, AI chips, and manufacturing equipment that China desperately needs to modernize its economy and military.

Washington can also sanction Chinese banks, restrict technology transfers, and rally allies (such as Australia, Japan, and the EU) to collectively pressure Beijing.

China cannot simply dictate terms without facing significant retaliation.

The Fundamental Challenge: Processing Bottleneck

Here lies the central strategic problem

Even if the U.S. successfully secures mining partnerships in Australia, Africa, and Ukraine, it faces a crippling midstream processing bottleneck.

Raw, rare earth ore is useless without refining and separation, and China controls approximately 90% of the global processing capacity.

Building rare earth processing hubs outside China requires.

Massive capital investment in complex chemical separation facilities

Energy infrastructure capable of supporting extraordinarily energy-intensive operations (rare earth processing consumes 15% of global electricity in mining sectors)[csis]

Environmental permits to handle toxic waste, radioactive residues, and acidic wastewater

Technical expertise that has migrated mainly to China over the past 30 years

Economic viability amid potential Chinese market flooding to undercut competitors

Experts estimate it will take at least a decade to build significant rare earth processing capacity outside China, even with aggressive government support.

Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths, the only major non-Chinese refiner, produces just 16,000-19,000 metric tons annually compared to China’s massive scale.

The company’s planned heavy rare earth facility in Texas has been delayed due to permitting issues.

Brazil’s Serra Verde rare earth project—a Minerals Security Partnership priority—already has its ore locked into offtake agreements with China for processing because no viable Western alternative exists.

This pattern will continue until processing capacity is built, perpetuating the very dependence the U.S. seeks to escape.

Global Reserves vs. China: The Numbers

Global rare earth reserves (2025):

China: 44 million metric tons (44% of global reserves)

Brazil: 21 million metric tons (21%)

India: 6.9 million metric tons (6.9%)

Australia: 5.7 million metric tons (5.7%)

Russia: 3.8 million metric tons (3.8%)

Vietnam: 3.5 million metric tons (3.5%)

United States: 1.9 million metric tons (1.9%)

Greenland: 1.5 million metric tons (1.5%)

Tanzania: 890,000 metric tons (0.9%)

While China possesses the most significant reserves, it holds less than half of the global total.

Brazil, India, and Australia combined hold 33.6 million metric tons—76% of China’s reserves.

The strategic issue is not geological scarcity, but industrial dominance: China mines 77% of global production and processes 90%, creating a stranglehold that far exceeds its natural resource base.

Conclusion

From a geopolitical perspective, the rare earth struggle exemplifies asymmetric interdependence—a situation in which mutual dependence exists, but one party (China) holds significantly greater leverage.

Beijing has weaponized rare earths multiple times: against Japan in 2010, threatened against the U.S. during Trump’s first term, and now through comprehensive export controls in 2025.

The Paradox of Plenty

The world possesses ample rare earth reserves; yet, China’s industrial advantage—built through environmental arbitrage, state subsidies, and strategic patience—has proven exceedingly difficult to counter.

Western nations face the “China Inc.” model: a state-capitalist system that tolerates pollution, labor exploitation, and unprofitable operations to achieve long-term strategic objectives.

The Time Dimension

Perhaps the most crucial factor is time.

Even with unprecedented investment, building alternative rare earth supply chains—particularly processing capacity—will require 10-15 years.

During this period, the U.S. and allies remain vulnerable to Chinese coercion.

This creates a dangerous window where Beijing might press its advantage before diversification efforts bear fruit.

The Cooperation Question

China will work together with the U.S. when the costs of confrontation outweigh the benefits of coercion.

Rare earth restrictions impose costs on China as well—accelerated Western investment in alternatives, potential loss of market share, economic retaliation, and diplomatic isolation.

A complete cutoff would be economically catastrophic for both nations, creating strong incentives for negotiated compromise despite aggressive rhetoric.

The Long Game

Ultimately, the U.S. strategy must focus on building resilient, diversified supply chains that reduce, though likely never eliminate, dependence on Chinese processing.

This requires sustained political commitment beyond election cycles, international coordination with allies, acceptance of higher costs and environmental trade-offs, and patient industrial policy spanning decades, not years.

The rare earth struggle illuminates a broader truth of 21st-century geopolitics: control over critical supply chains constitutes a form of power as significant as military strength or financial leverage.

China recognized this decades ago and acted accordingly. The United States is now paying the price for that strategic foresight gap—and attempting, perhaps belatedly, to close it.