Parallels between Cobalt Mining in Africa and Rare Earth Mining in China

Executive Summary

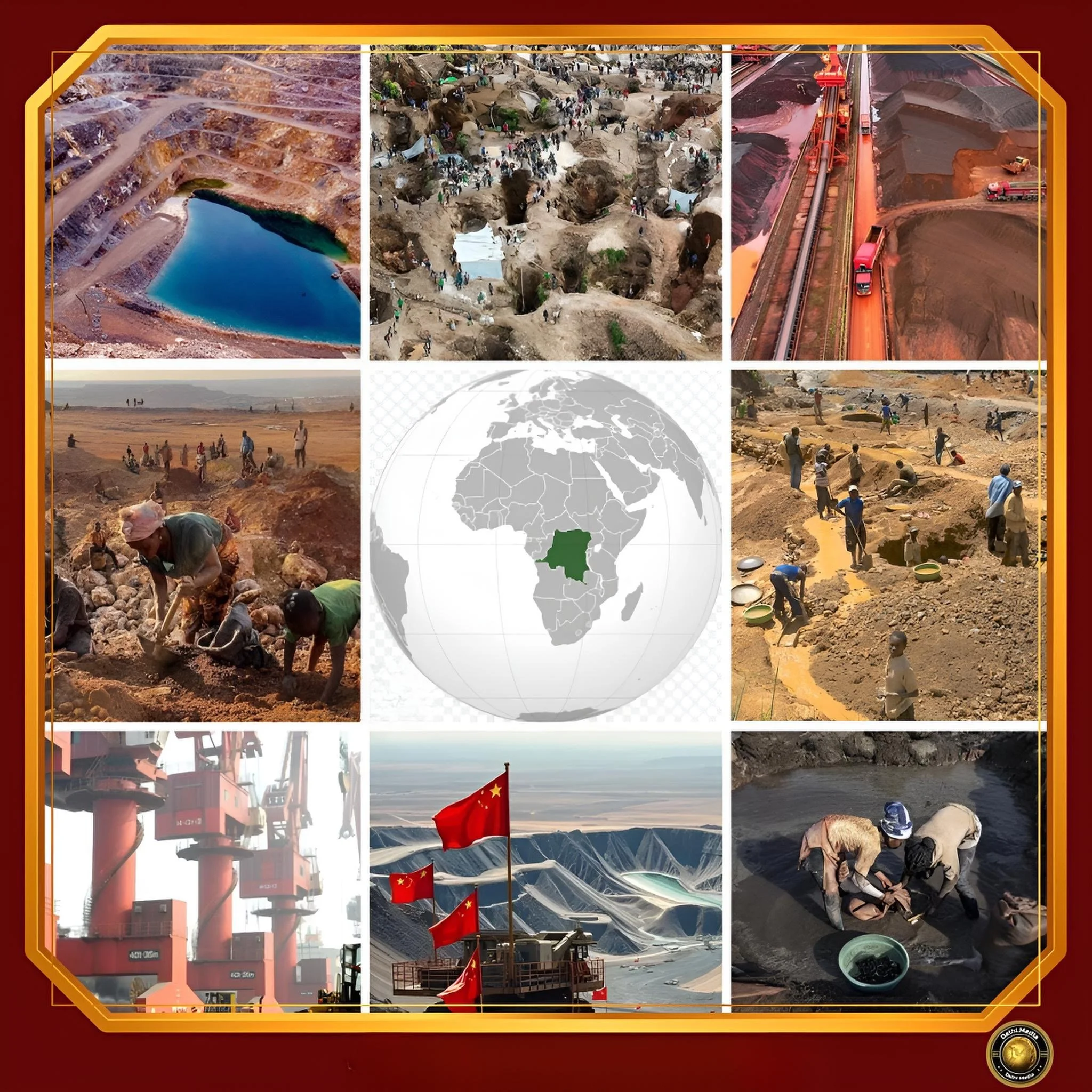

The extraction of cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo and rare earth elements in China present striking structural analogies in how developing and resource-abundant nations bear disproportionate environmental and human costs while capital-exporting countries capture value through downstream processing and manufacturing.

Both sectors exhibit systematic patterns of resource extraction premised upon regulatory forbearance: the DRC mining environment remains characterized by minimal labor protections, with 97 percent of workers laboring within informal sectors where child labor persists alongside inadequate safety standards; similarly, China’s rare earth operations have historically flourished because, as a 2019 U.S. Army report documents, the nation remains “less burdened with environmental or labor regulatory requirements” that would substantially increase extraction costs.

In both cases, the geographic concentration of raw material production—the DRC supplies 68-70 percent of global cobalt mine output while China controls approximately 65 percent of mined rare earths—has created corresponding environmental devastation through tailings contamination, soil degradation, groundwater poisoning, and deforestation, conditions that are intensified rather than ameliorated by accelerating global demand for these minerals ostensibly required for the clean energy transition.

This extractive architecture perpetuates what development scholars term a “port-to-pit” dependency model, wherein resource-rich nations export unrefined commodities while accumulating environmental liabilities, whilst external actors—particularly China through its 64 percent dominance of global cobalt refining and 88 percent control of refined rare earth supply—consolidate value capture through monopolistic processing capabilities and technological mastery.

The confluence of these extractive patterns with geopolitical competition and supply chain monopolization has created a secondary layer of parallelism wherein both cobalt and rare earth sectors demonstrate how mineral dominance becomes weaponized for international leverage and how environmental-justice deficits reproduce colonial-era subordination dynamics.

China’s strategic consolidation of rare earth supply chains—from mining through refining and magnet production—has enabled it to exercise explicit geopolitical coercion, exemplified by its 2010 embargo on rare earth exports to Japan and its December 2025 implementation of restrictions denying export licenses to any entities affiliated with foreign militaries, effectively creating a technological blockade.

Contemporaneously, the DRC’s February 2025 assertion of export controls over cobalt represents an nascent attempt to reverse asymmetrical value extraction; however, this initiative confronts a structural disadvantage absent in China’s positioning: whilst the DRC generates 68 percent of global mine production, Chinese state-owned enterprises control 64 percent of refining capacity, meaning Congolese supply leverage operates within circumscribed parameters.

Both supply chains consequently demonstrate how mineral wealth concentration, when divorced from indigenous processing and manufacturing capabilities, transforms resource abundance into geopolitical vulnerability for resource-exporting states while simultaneously concentrating environmental degradation and labor

Introduction

The core parallel is this: both cobalt in the DRC and rare earths in China are indispensable to the green and digital economy, and in both cases, global consumers enjoy cheap “clean” technologies because local communities absorb the environmental destruction and health risks.

The planetary transition away from fossil fuels has been built on geographically concentrated extractive frontiers that function as sacrifice zones.

Structured comparison

Strategic Role in Global Supply Chains

Both sectors sit at chokepoints in key 21st‑century supply chains.

Cobalt in the DRC / Africa

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) produces roughly 70% of the world’s cobalt, a critical input for high‑energy‑density lithium‑ion batteries used in EVs, electronics, and some grid storage.

Cobalt demand is driven mainly by electric vehicles and energy storage; by early 2030s, analysts forecast demand of around 400,000 tonnes a year and a structural market deficit as demand outpaces supply.

DRC’s government has recently used export bans and quota systems to push up prices and gain leverage over the market, revealing how concentrated supply can become a geopolitical tool.

REE in China

China produces and processes the overwhelming majority of the world’s rare earth elements (REEs), essential for EV motors, wind turbines, smartphones, permanent magnets, and military systems.

This dominance stems partly from tolerating environmental and social costs that made Chinese rare earths dramatically cheaper than Western production—at times one‑third to one‑fifth of U.S. prices.

Control over REE mining and especially refining has given Beijing a strategic lever in trade and technology disputes; export controls on specific rare earths and magnets have already been used in response to geopolitical tensions.

Parallel

In both cases, a single country (DRC for cobalt, China for rare earths) sits at the heart of a critical‑minerals bottleneck, with the ability to influence global supply, pricing, and downstream industries.

Political Economy: How Cheap Metals Are Produced

Externalization of Costs

In both DRC cobalt and Chinese rare earths, low global prices were achieved by shifting costs onto local communities and environments rather than through genuine productivity gains.

For Chinese rare earths, early industry growth relied on ignoring environmental damage and worker safety, and tolerating smuggling and illegal mining.

This drove down the export price of rare earths to a fraction of U.S. levels, effectively winning a near‑monopoly by sacrificing local environments and labor protections.

In DRC, cobalt extraction—especially in artisanal and small‑scale mining (ASM)—relies on extremely low wages, informal labor, and near‑total absence of safety or environmental protection, making Congolese cobalt some of the cheapest on earth despite its human cost.

Weak or Complicit Governance

In Chinese rare earth regions (Inner Mongolia, Jiangxi, Guangxi), local governments often turned a blind eye or colluded with illegal or quasi‑legal operators, sometimes being directly linked to the state‑owned enterprises (SOEs) doing the mining.

In the DRC, central and provincial authorities often lack capacity and are vulnerable to corruption.

Industrial operators and traders exploit regulatory gaps, while artisanal mining operates in a gray zone where local elites, security forces, and foreign buyers all take cuts.

Parallel

Both systems generated “competitive advantage” not through higher efficiency but by socializing environmental and health costs onto marginalized populations, with local authorities unable or unwilling to enforce protections.

Environmental Degradation and “Sacrifice Zones”

The environmental footprint in both places is extreme, but manifests differently given geology and processing methods.

Cobalt mining in the DRC

Heavy metal contamination and acid mine drainage have polluted soils and water near cobalt and copper mines in Katanga.

Residents around mining hubs like Kolwezi and Lubumbashi show elevated levels of cobalt and other metals in blood and urine, especially children.

Studies have linked exposure to increased birth defects and developmental problems, and large areas around industrial mines are described as effectively uninhabitable “sacrifice zones”.

Tailings dam failures and poorly managed waste dumps have caused local flooding, destruction of farmland, and long‑term soil contamination.

Rare earth mining in China

At Bayan Obo (near Baotou, Inner Mongolia), the world’s largest light rare earth mine, decades of mining and processing produced a vast tailings lake filled with radioactive and chemically contaminated sludge.

Thorium‑laden and acidic waste was long discharged with minimal containment, leading to air and water contamination and documented developmental disorders in local children.

In Ganzhou and other ionic‑clay deposits in Jiangxi, rare earths were extracted using repeated irrigation of hillsides with acidic solutions.

This stripped vegetation, eroded hills down to bare red clay, and allowed acids and heavy metals to seep into soils and groundwater, rendering areas almost impossible to restore naturally.

These regions have reported “cancer villages”—clusters of elevated cancer and birth defect rates linked to long‑term exposure to mining pollution, with hundreds of abandoned rare earth mines and hundreds of millions of tons of tailings.

Parallel

In both cases, mining districts have become ecological sacrifice zones:

(1) Poisoned water

(2) Destroyed farmland

(3) long‑term health risks are treated as acceptable collateral for providing the world with critical inputs to clean energy and high‑tech products.

Human and Social Costs

Labor conditions and community impacts

DRC cobalt

An estimated 40,000 children work in cobalt mines, many in dangerous underground artisanal pits, for a few dollars a day, with no protective gear.

Artisanal miners (adults and children) commonly earn around 2 USD per day, often below the DRC’s official minimum wage and far below the risks they assume.

Tunnel collapses and suffocation are frequent in hand‑dug shafts; miners routinely describe their work in terms of high daily risk of death or crippling injury.

Communities have suffered forced evictions to make way for industrial mines, often with inadequate compensation and relocation to areas lacking water and basic services.

Chinese rare earths

While child labor is not a systemic feature as in the DRC, workers and nearby villagers have borne chronic exposure to toxicants—fluoride, arsenic, heavy metals, radioactive materials—leading to increased disease burdens, particularly cancers and developmental disorders in some regions.

Many villagers in Jiangxi and Inner Mongolia reported being pushed into illegal or semi‑legal mining as traditional livelihoods (farming, herding) became non‑viable due to land degradation and low returns, mirroring the economic coercion seen in DRC cobalt communities.

Residents frequently describe being unable to move away due to poverty, trapped in polluted villages where crops die and water sources are unsafe.

Rights, voice, and repression

In both contexts, affected communities have limited ability to organize or seek remedy.

In the DRC, informal miners operate outside formal protections; challenging large concession holders or security forces can be dangerous.

In China, attempts to mobilize against rare earth pollution have faced legal and political repression; environmental activists and lawyers involved in such cases have been harassed or had licenses revoked.

Parallel

In both cases, vulnerable, often rural communities with weak political voice bear disproportionate risks, with few channels to contest dangerous practices or demand compensation.

Illegal and Artisanal Mining

DRC cobalt pervasive artisanal mining

Artisanal and small‑scale mining (ASM) accounts for a significant share of DRC cobalt output—often cited around 20–30%—and involves hundreds of thousands of miners operating with hand tools, informal traders, and little oversight.

ASM cobalt is deeply embedded in global supply chains: it is sold to middlemen, mixed with industrial output, and eventually ends up in batteries used by major global brands.

China rare earths: long history of illegal mining

China’s rise in rare earths involved extensive illegal mining and smuggling, especially in southern ionic‑clay deposits, where small operators leached hillsides with acids and sold unregistered product into the supply chain.

The central government has repeatedly launched crackdowns and consolidation drives, but satellite and investigative reporting show continued illegal operations and waste dumping even after formal tightening.

Parallel

In both cases, informal or illegal extraction is not peripheral but structurally important to the sector’s economics.

It keeps costs low but makes traceability, environmental management, and labor protections extremely difficult.

State Response and Regulatory Trajectories

China: from laissez‑faire pollution to controlled dominance

After decades of laissez‑faire environmental policy in rare earth regions, Beijing has spent billions of dollars trying to remediate or at least contain the worst damage, including reinforcing tailings ponds, relocating residents, and consolidating mines under a handful of SOEs.

The state has moved from tolerating widespread illegal mining to enforcing tighter central control, partly to improve environmental outcomes but also to strengthen strategic leverage and pricing power.

Nevertheless, recent investigations show that contamination, dust emissions, and health risks remain serious in key hubs like Baotou and Ganzhou.

DRC: tentative moves toward formalization and control

The DRC has created Entreprise Générale du Cobalt (EGC) to buy, formalize, and market artisanal cobalt, aiming to improve working conditions and traceability.

In 2025 EGC announced the first 1,000 tonnes of traceable artisanal cobalt, presenting this as proof that safer, formalized ASM is possible.

Pilot projects such as the Mutoshi site showed that with controlled entry, safety protocols, and child‑labor exclusion, artisanal mining can operate without fatal accidents while meeting international buyers’ standards.

However, coverage remains limited, and the bulk of ASM cobalt still comes from largely unregulated sites, with persistent child labor, dangerous pits, and exploitative buying practices.

Parallel

Both countries are belatedly trying to clean up industries that were built on systemic externalization.

China has gone further in consolidating and centralizing control; the DRC is at an earlier stage, with a much weaker state, heavier foreign corporate presence, and far less fiscal room to fund remediation.

Geopolitical Leverage and Vulnerabilities

Shared features

Both cobalt and rare earths are now recognized as “strategic” or “critical” minerals in U.S., EU, and other national policies, prompting efforts to diversify supply and reduce dependence.

Supply concentration has enabled both Beijing and Kinshasa (to a lesser degree) to experiment with export restrictions, quotas, and price management, using minerals as leverage in broader negotiations.

Key differences

China controls not only mining but also mid‑stream and downstream processing and manufacturing (separation, magnet production, EV and wind industries).

This gives it deep structural power in the value chain.

The DRC, by contrast, exports mostly raw or semi‑processed cobalt.

Refining and high‑value manufacturing are dominated by foreign firms, particularly in China.

This leaves Congo with resource dependence but limited bargaining power, despite geological importance.

Parallel

In both, mineral wealth translates into geopolitical relevance—but China turns this into industrial and technological advantage, while the DRC remains largely a low‑income, extraction‑dependent state whose communities see little of the value.

Conclusion

Cobalt mining in the DRC and rare earth extraction in China are mirror images of a single structural pattern in the green transition:

Both supply indispensable inputs to “clean” technologies—EVs, wind turbines, electronics—but

Both have been built on systematic externalization of environmental and health costs onto marginalized communities, and

Both are embedded in political economies where weak or captured local governance has enabled exploitation in the name of global competitiveness.

The parallels are stark

Mining regions in Katanga (DRC) and in Bayan Obo/Ganzhou (China) have functioned as sacrifice zones, where poisoned water, destroyed land, and elevated disease burdens are normalized as the price of development.

Residents at both ends describe being trapped by poverty in polluted environments they did not choose, while powerful actors—multinationals, SOEs, urban consumers in rich countries—reap the benefits.

In both cases, belated state efforts at regulation and formalization have not fundamentally altered the asymmetry: the world still expects cheap critical minerals, and much of that low price continues to be paid in Congolese and Chinese bodies rather than in corporate balance sheets.

There are also important differences: China has leveraged rare earths into a full industrial ecosystem and geopolitical asset, while the DRC remains largely stuck at the raw‑material export stage.

Labor exploitation in the DRC is more overt—child labor, deadly artisanal pits—while in China the harm is more often chronic and environmental, manifesting as cancer clusters and long‑term health impacts.

Analytically, the key lesson is that the “clean” energy and digital transitions are not immaterial.

They rely on highly material frontiers of extraction—from Congo’s cobalt belts to China’s rare‑earth basins—where costs are spatially displaced.

Any serious attempt to make these transitions genuinely just and sustainable must therefore:

(1) Internalize environmental and health costs into mineral prices,

(2) Strengthen labor and community rights at mining frontiers, and

(3) Distribute value along the supply chain so that producing regions are not merely sacrificial hinterlands for a decarbonizing global core.

Until that happens, the parallels between cobalt mining in Africa and rare earth mining in China will remain an indictment of how the world is financing its “green” future.