India’s AI Impact Summit 2026: Power, Prudence and the Global AI Commons -Part II

Executive summary

India’s AI Impact Summit 2026 at Bharat Mandapam in New Delhi is more than a technology conference.

It is an experiment in how emerging powers use artificial intelligence to renegotiate place, power and responsibility in the international system.

Coming after earlier AI gatherings in the United Kingdom, South Korea and France, this summit is the 1st to take place in the Global South and is explicitly framed around “People, Planet, Progress”, not only “safety” or “innovation”.

The summit’s architecture reveals a dual ambition.

Domestically, India wants AI to sit on top of its digital public infrastructure and to drive growth, welfare delivery and state capacity.

Internationally, New Delhi wants to reposition itself from “rule‑taker” to “rule‑maker” by convening a conversation on the “global AI commons” that includes developing economies, not just trans‑Atlantic powers and a handful of corporations.

This ambition is reflected in the programme’s seven thematic “chakras”, which range from safe and trusted AI to inclusive growth and science‑driven innovation, and in the deliberate mix of political leaders, corporate chiefs, researchers and youth innovators.

Within this structure, five speakers embody the summit’s central lines of debate.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi used his opening address to launch a MANAV framework for AI – moral and ethical, accountable, nationally sovereign, accessible and inclusive, valid and legitimate – and to insist that AI must be democratized as a tool for human welfare rather than concentrated as an instrument of control.

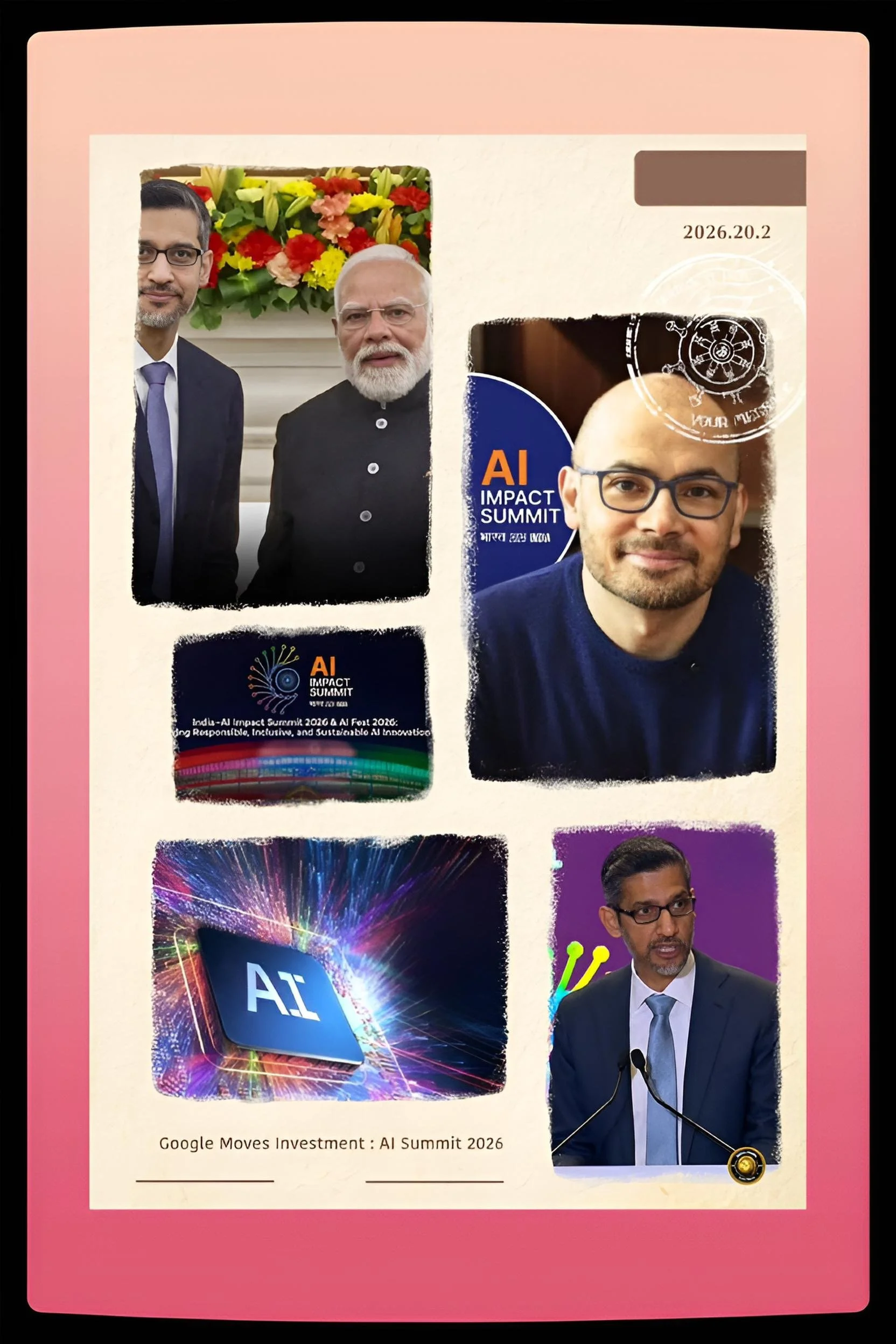

Google chief executive Sundar Pichai presented a concrete infrastructure agenda, including a $15 billion AI hub in Visakhapatnam and new subsea cables, casting India as both laboratory and launchpad for AI deployed at scale.

OpenAI chief executive Sam Altman warned that, at current rates of progress, the world may be only a few years away from early forms of superintelligence and a situation in which more than half of global “thinking capacity” sits inside data centres.

Sam praised India’s rapid adoption of tools such as ChatGPT and Codex, but also argued that access, adoption and agency must advance together if AI is not to deepen global inequality.

French President Emmanuel Macron brought Europe’s regulatory project and his own notion of “digital civilisation” to Delhi, advocating a path between a United States–China duopoly and urging India to join a coalition that links strong AI rules, decarbonised infrastructure and protection of children online.

Demis Hassabis, the scientist‑entrepreneur behind Google DeepMind, set out a five to eight year horizon for artificial general intelligence (AGI), highlighting both the promise of AI‑driven discovery in science and medicine and the need for international coordination around systemic risks.

These five interventions sit atop a dense layer of developments: major investment announcements, pilots of sovereign Indian language models, AI‑enabled public‑sector projects, and increasingly vocal civil‑society warnings about surveillance, bias and deepfakes.

The cause‑and‑effect dynamic that emerges is clear.

Economic and geopolitical incentives push India and its partners toward rapid deployment and large‑scale infrastructure, while the social and democratic risks of that same acceleration are only beginning to be understood.

The summit’s lasting significance will depend on whether its rhetoric of a “global AI commons” hardens into institutions and norms that widen access and uphold rights, or whether it becomes a ceremonial interlude in a more closed and unequal AI order.

Introduction

India, AI and the struggle for the global commons

Artificial intelligence has moved from the periphery of policy debate to the core of economic strategy and security planning.

Frontier models now write code, summarise legal documents, generate realistic synthetic media, assist in scientific discovery and increasingly act as “agents” that can plan and execute multistep tasks across digital systems.

Underneath these breakthroughs lie three highly concentrated inputs: advanced chips and compute clusters, large datasets and elite research talent.

The political question is who controls those inputs and under what rules.

For much of the last decade, the de facto centre of gravity for AI has been a narrow corridor between Silicon Valley, Seattle and a few emerging hubs in China and Europe.

India played a secondary role as a reservoir of coders and a vast digital market rather than as a full‑spectrum AI power.

That division of labour mirrored wider patterns of globalisation, in which advanced economies concentrated on high‑value innovation while emerging economies supplied labour and consumption.

The India AI Impact Summit 2026 is one of the clearest attempts yet by a major developing country to contest that pattern by hosting, convening and partly steering the global conversation on AI.

India’s case for this role rests on 3 main pillars.

First is its digital public infrastructure: Aadhaar for identity, the Unified Payments Interface for instant transactions, DigiLocker for document storage and Ayushman Bharat for health records.

Together, these form an “India Stack” that has allowed the government and private firms to build services for hundreds of millions at low marginal cost.

Second is demography and skills: a young population, a large pool of engineers and data scientists, and a diaspora embedded in leading global technology firms.

Third is an increasingly assertive diplomatic agenda that treats digital norms, data governance and AI standards as domains where India can speak for, and with, the wider Global South.

The summit’s Global South framing is not merely cosmetic.

Many developing economies fear that AI will repeat earlier patterns of exclusion: rich countries accumulate compute and data, set rules and export AI‑enabled products, while poorer ones consume and adjust.

New Delhi’s message is that, at least in principle, there is an alternative. In this alternative, digital public goods, multilingual models and shared compute resources underpin a “commons” in which wider groups can access and shape AI systems.

Whether that vision is realised depends on the choices made now about infrastructure, governance and alliances.

History and Current Status

India’s AI project

The road to the India AI Impact Summit 2026 runs through a series of earlier decisions that reshaped India’s digital landscape.

The rollout of Aadhaar from 2010 onwards, and its later linkage to welfare payments and bank accounts, gave India a near‑universal biometric identity system.

The launch of UPI in 2016 created an open, interoperable payments rail that now handles around 20 billion transactions per month, supporting everything from street vendors’ sales to government benefit transfers.

These platforms, combined with cheap data services and smartphone penetration, pulled hundreds of millions into formal financial and digital systems.

Over time, policymakers and technologists began to describe these infrastructures as “digital public goods”: open, modular components that the state, startups and civil society could reuse to build new services.

This narrative, promoted in international forums, recast India not just as a consumer of Western platforms but as an exporter of digital governance models to other developing states. Pilot projects using elements of the India Stack in Africa and Southeast Asia reinforced this self‑image.

AI entered this picture in phases.

Initially it appeared in narrow use‑cases: fraud detection in payments, conversational bots for citizen services, early diagnostic tools in health. But as large language models and generative AI systems matured, both government and industry elites began to see AI as the next layer atop the digital public‑goods stack.

By 2023–2024, India’s national AI discourse had coalesced around the IndiaAI Mission, a comprehensive programme to build national compute infrastructure, sovereign models, open datasets, skilling pipelines and startup support schemes.

The IndiaAI Mission rests on seven pillars.

It envisages a national AI compute grid of more than 10,000 graphics processing units in the short term, with expansion to significantly larger capacities; a family of foundational models trained on Indian data, including low‑resource languages; a suite of high‑quality, anonymised datasets for research and innovation; application programmes targeting key sectors such as agriculture, health, education and justice; future‑skills initiatives across schools and universities; catalytic funding for AI startups; and a safe‑AI framework for risk assessment and governance.

Regional events through 2025 and early 2026, including a major pre‑summit in Lucknow, were used to align state governments and line ministries with this agenda.

Officials from health, agriculture, rural development and policing were exposed to practical AI applications and to the policy questions they raise.

This process helped ensure that by the time world leaders arrived in Delhi, India could present itself as not only a convener of AI debates but as a country with concrete deployments and a coherent national strategy.

On the global stage, India watched as the United Kingdom convened the Bletchley Park AI Safety Summit in 2023, followed by ministerial meetings in Seoul and a planned summit in France.

Meanwhile, the European Union pushed ahead with its AI Act, the United States issued executive orders alongside export controls on chips, and China advanced its own content‑centric AI regulations.

What these initiatives had in common was that they emerged in advanced economies and largely reflected their interests and risk perceptions.

The India AI Impact Summit 2026 is India’s answer: a summit that includes many of those actors but is geographically, politically and discursively anchored in the Global South.

Key developments at the India AI Impact Summit 2026

Narendra Modi’s MANAV, Deepfakes and AI as Civlisational Choice

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s opening speech set the summit’s tone.

He framed AI as a civilisational crossroad comparable to the discovery of atomic power.

Just as atoms gave humanity the ability to either destroy itself or multiply its capacities, he argued, AI compresses in silicon an extraordinary combination of promise and peril.

The key question, he said, is no longer whether AI can do certain tasks, but whether humanity will choose to use it in a way that strengthens dignity and democracy.

Modi’s MANAV framework gave this intuition a policy shape.

“Moral and ethical” recalled concerns about bias, discrimination and opaque decision‑making in areas such as credit scoring, policing and welfare delivery.

“Accountable” pointed toward institutional arrangements in which those deploying AI are answerable when systems cause harm.

“National sovereignty” signalled India’s insistence on retaining control over critical datasets, infrastructure and standards, even as it embraces global cooperation.

“Accessible and inclusive” reflected the summit’s avowed focus on the Global South, rural users, women and marginalised communities.

“Valid and legitimate” underscored the need for scientific robustness and public consent.

A central concern in Modi’s speech was the erosion of trust caused by deepfakes and synthetic media. He described this as a direct threat to democracy, social harmony and personal reputation.

To respond, he proposed that AI‑generated content carry clear authenticity labels, analogous to nutrition labels on food packages or health warnings on cigarettes.

The idea is that watermarks, provenance standards and digital‑signature schemes can give citizens a fighting chance to distinguish authentic records from fabricated ones.

Without such defences, he warned, societies risk descending into an epistemic fog where visual evidence can no longer anchor shared reality.

Modi also placed India’s material capabilities at centre stage. He presented a picture of an emerging AI ecosystem that spans semiconductor design, quantum research, data centres, startups and skill development programmes.

He stressed India’s diversity as a “stress‑test” for AI: if models can serve users across 20+ official languages, wide income disparities and varied literacy levels, they can adapt to almost any setting.

Modi’s closing slogan – “Design and develop in India, deliver to the world, deliver to humanity” – converted that argument into a diplomatic sales pitch.

Sundar Pichai

Infrastructure, Skilling and the Risk of an AI divide

Sundar Pichai’s remarks complemented Modi’s political vision with a corporate strategy grounded in infrastructure.

He cast AI as the most significant computing shift in a generation, one that will reconfigure how societies solve problems from early disease detection to supply‑chain resilience and disaster response.

For countries like India, he argued, the question is whether they can harness this shift to leapfrog older industrial stages.

The centrepiece of Pichai’s speech was Google’s commitment to a $15 billion AI hub at Visakhapatnam.

He described it as an integrated site for large‑scale data centres, specialised AI compute clusters and a new international subsea cable landing station.

This facility, together with additional undersea cables connecting India with the United States and Southern Hemisphere locations, would expand India’s role as a connectivity hub, not just a consumer endpoint.

In strategic terms, these moves embed Google’s infrastructure deeply within India’s digital and energy systems, while giving India more leverage over regional data flows.

Alongside infrastructure, Pichai announced a $30 million AI for Science Impact Challenge through Google.org, designed to support research that uses AI to accelerate discovery in fields such as climate science, biology and materials.

He also highlighted expanded skilling programmes that aim to reach thousands of Indian schools and universities with AI literacy, teacher training and student projects.

Pichai warned that without deliberate action, the digital divide could become an AI divide. In his view, this would happen if advanced AI tools, compute and reliable connectivity remain clustered in a few rich regions and firms.

The result would be a world where some societies can use AI to multiply productivity and solve complex problems, while others are relegated to passive consumption.

To avoid this, he argued for investment in local‑language tools, affordable access, open‑source components and public‑interest AI projects that address problems specific to developing economies.

Sam Altman

Super-Intelligence, Bio-Models and the Politics of Access

Sam Altman’s speech stood out for its blunt timeline and its focus on structural risk. He disclosed that over 100 million people in India use ChatGPT every week, and that more than one third of those users are students.

India, he said, is also the fastest‑growing market for OpenAI’s Codex coding agent.

These figures, beyond their marketing value, show how deeply AI systems are already woven into India’s knowledge economy and daily life.

Altman then sketched a near‑term trajectory in which early forms of superintelligence emerge within a few years. At current rates, he suggested, by 2028 more of the world’s intellectual capacity could reside inside data centres than in human brains.

That shift would massively increase potential output but also concentrate power in whoever controls the data centres, models and energy supplies. Wages, prices and entire supply chains would be reshaped as AI and robotics erode old bottlenecks.

In this context, Altman proposed a three-part lens: access, adoption and agency. Access refers to the physical availability of AI tools and connectivity; adoption to the integration of those tools into schools, workplaces and services; agency to the capacity of individuals and communities to use AI creatively and critically to advance their own goals.

If access and adoption grow but agency lags, AI’s benefits will flow mainly to those who already hold capital and institutional power. Aligning all three dimensions becomes, in his view, the central political economy challenge.

Altman’s comments on risk went beyond generic concerns about bias. He singled out biomodels – AI systems that can help design biological agents – as a particular danger if released openly. In the wrong hands, such tools could lower barriers to creating or modifying pathogens.

For this reason, he argued that open‑source release is not always appropriate and that even private labs cannot manage such risks alone.

He advocated iterative deployment, where frontier systems are rolled out gradually, monitored in real‑world conditions and accompanied by evolving safeguards, including some form of international oversight.

Emmanuel Macron

European Rules, Decarbonized AI and Strategic Autonomy

Emmanuel Macron used his keynote to link India’s digital public infrastructure to Europe’s regulatory philosophy and to a broader vision of strategic autonomy.

He began by praising India’s digital achievements: a biometric identity system that covers 1.4 billion people, a payment system that clears around 20 billion transactions per month and digital health infrastructure that reaches hundreds of millions.

For Macron, these are not simply technical platforms, but the foundation of a new kind of democratic sovereignty.

He then presented the European Union’s AI Act as evidence that open societies can proactively set the boundaries of acceptable AI use.

The Act bans certain “unacceptable risk” systems, such as indiscriminate real‑time biometric surveillance in public spaces, and imposes strict obligations on high‑risk applications.

Rather than viewing regulation as a brake on innovation, Macron framed it as a precondition for sustainable innovation that commands public trust.

Macron announced that France and its partners plan to invest more than €58 billion in data centres and AI infrastructure powered largely by low‑carbon energy, including nuclear.

He argued that decarbonised power is becoming a strategic resource for AI, since rising compute demand could otherwise collide with climate commitments.

In this sense, European nuclear and renewable capacity becomes a bargaining chip in AI geopolitics, just as chip‑fabrication capacity has become in recent years.

Crucially, Macron positioned Europe and India as potential co‑authors of a “third way” in AI, between a United States‑centric market‑driven model and a China‑centric state‑surveillance model. This third way would combine open markets with strong protections for rights and pluralism.

As part of that agenda, he highlighted efforts to restrict social‑media access for children under 15 and invited India to join a coalition to protect minors from digital harms.

In the AI context, this is presented as part of a wider effort to ensure that algorithms and attention‑driven platforms do not erode mental health and democratic debate.

Demis Hassabis

Agentic Systems, Scientific Discovery and Global Coordination

Demis Hassabis, speaking as a leading AI scientist, anchored his remarks in the frontier of research.

He recalled how DeepMind’s AlphaFold transformed structural biology by predicting protein structures at scale, illustrating how AI can compress years of lab work into hours. He argued that the next phase will see more autonomous, agentic systems that can decompose goals, plan, call tools and act across digital environments, effectively functioning as general‑purpose problem‑solvers.

Hassabis estimated a five to eight year horizon for artificial general intelligence – systems that can match or exceed human performance across most cognitive tasks – and suggested that such systems could revolutionise not only drug discovery and climate modelling but also materials science, agriculture and process optimisation in industry.

He emphasised that India, with its large pool of young engineers, growing research base and complex real‑world challenges, is well placed to lead in applying these capabilities if it continues to invest in computing infrastructure and fundamental research.

At the same time, Hassabis echoed others in warning that technical progress alone cannot guarantee good outcomes.

Autonomous systems that can write and execute code, manipulate online environments or discover new chemical pathways could be misused for cyberattacks, disinformation or weapon development. No single company or state can anticipate all such failure modes.

For him, summits like those at Bletchley Park, in Paris and now in Delhi are early attempts to build a scaffolding of international norms, shared evaluation methods and emergency protocols.

He welcomed India’s decision to host a summit that gives Global South voices a larger role, arguing that without their participation any AI governance regime will lack legitimacy and practical reach.

In his view, the task now is to move from occasional summitry to more permanent mechanisms for joint monitoring, information‑sharing and coordinated responses to systemic AI incidents.

Latest Facts, Emerging Concerns and Unresolved Questions

Beyond these headline speeches, a series of concrete facts and controversies shape the summit’s texture.

Organizers report that the summit’s expo and public events have drawn more than 70,000 visitors on the opening day and are expected to attract upwards of quarter million attendees over 5 days, making it arguably the largest AI gathering yet by physical participation.

The Indian government and its partners have signaled potential AI‑related investment commitments in the range of $100 billion over the coming years, spanning data centres, semiconductor manufacturing, cloud infrastructure and AI‑enabled industrial modernization.

The summit also serves as a launch platform for several India‑centric initiatives.

These include sovereign Indian language models designed to run efficiently on local hardware, AI‑powered tools integrated into health and agriculture schemes, and innovation programmes such as AI for All, AI by HER and YUVAi, which target inclusive AI literacy, women‑led innovation and youth entrepreneurship respectively.

These initiatives are meant to demonstrate that AI is not an abstract frontier technology but a practical instrument of development.

Yet concerns shadow this narrative. Bill Gates, originally advertised as a keynote speaker, ultimately did not attend, with reports linking his withdrawal to renewed scrutiny over his past associations and the potential political optics of sharing a platform in Delhi.

Civil‑society groups and digital‑rights advocates have used the summit to highlight the risks of AI‑driven surveillance, predictive policing and automated content moderation in a context of already strained civil liberties.

They argue that without strong, independent oversight and legal safeguards, AI could entrench existing biases and amplify majoritarian pressures.

There are also structural worries about global inequality in AI capacity.

Export controls on advanced chips, concentration of leading models in a few Western and Chinese firms and the clustering of hyperscale data centres in specific geographies raise doubts about whether talk of a “global AI commons” can be translated into practice.

Altman’s warning about biomodels, and Hassabis’s concerns about agentic systems, underscore that the very capabilities that make AI attractive for science and industry also create avenues for catastrophic misuse.

Modi’s focus on deepfakes and Macron’s push to ban certain uses of biometric surveillance express fears that democracies may struggle to retain control over their information environments.

Cause‑and‑Effect Analysis

India’s Strategic AI Gambit

Seen through a cause‑and‑effect lens, the India AI Impact Summit 2026 reflects several interacting forces. At the base lies the economic logic of AI.

High fixed costs in compute, data‑curation and model training pair with low marginal costs of deployment.

This pushes the system toward economies of scale and scope, favoring actors that can mobilize capital, talent and regulatory influence. Left unshaped, this logic would produce a world in which a few jurisdictions and corporations supply AI capabilities to everyone else.

India’s leadership recognizes this dynamic and is attempting to bend it in three ways.

First, by investing in national compute infrastructure and sovereign models, India hopes to reduce its vulnerability to external chokepoints in chips, cloud capacity and proprietary models.

This does not mean autarky, but rather a more resilient position in global value chains.

The cause here is the perception of strategic dependency; the effect sought is greater bargaining power and room for maneuver.

Second, by convening a globally visible summit in Delhi, India is trying to translate material assets into normative influence.

Hosting political leaders, corporate chiefs and researchers on its own soil gives India agenda‑setting power: it can define themes, shape joint communiqués and promote its digital public‑goods model as an example for others.

The cause is a desire to avoid being bound by standards and norms set elsewhere; the effect is an attempt to co‑author the emerging rulebook, especially for the Global South.

Third, by tying AI to development and inclusion narratives – from health and agriculture to education and women’s empowerment – India is building a domestic coalition for AI expansion.

Successful deployments that improve service delivery or income prospects can create constituencies in favour of continued investment and experimentation.

But this also creates path dependence: once AI becomes deeply embedded in state functions, reversing course in response to rights‑based critiques becomes politically harder.

The cause is the search for efficiency and growth; the effect could be both improved outcomes and heightened risks of technocratic overreach.

The interplay with global firms adds another layer. Companies like Google and OpenAI see India as a site to scale products, harvest data‑rich feedback and embed their infrastructure into a fast‑growing market.

India in turn leverages their capital and expertise to accelerate its AI ambitions.

This mutual dependence can produce positive‑sum outcomes: more compute, better tools, faster innovation. But it can also skew incentives toward rapid deployment and away from precaution, especially if competitive pressures push firms to offer ever more capable systems to secure market share.

The cause is global competition for AI leadership; the effect is a race dynamic that domestic governance will struggle to constrain.

At the international level, India is positioning itself as a bridge between regulatory blocs. Macron’s appeal to European–Indian cooperation fits neatly with New Delhi’s longstanding preference for strategic autonomy: close ties with Western democracies without formal alliance entanglements.

Simultaneously, India participates in United States‑led technology groupings and benefits from Western chip and cloud ecosystems.

The cause is a fragmented global order with competing regulatory philosophies; the effect is India’s attempt to arbitrate between them and to inject Global South concerns – development, access, linguistic diversity – into the conversation.

Future steps

From Summit Rhetoric to Institutional Reality

The summit’s ultimate value will depend on what India and its partners do in the next 3–5 years. Several trajectories are already visible.

On governance, India and other participants will need to operationalize the New Delhi Frontier AI Impact Commitments.

This implies building permanent capacities to measure AI’s economic, social and political effects, and to share those findings transparently.

Evidence‑driven policy requires robust datasets on, for example, job displacement and creation by sector, productivity gains in small firms, impacts on gender gaps, and the use of AI in state surveillance or welfare targeting. Without such data, debates will be dominated by anecdote and corporate narratives.

On technical evaluation, the summit’s emphasis on multilingual and context‑sensitive testing must translate into concrete benchmarks and audit practices.

Models deployed in India and across the Global South need to be evaluated in Indian languages and in realistic local scenarios, from rural health advice and agricultural extension to courtroom assistance and police work.

India could become a hub for such evaluation, hosting testbeds that other countries can plug into. The cause would be a deliberate push for inclusive benchmarks; the effect could be a more diverse and representative standard‑setting ecosystem.

On infrastructure and energy, Pichai’s Visakhapatnam hub and Macron’s decarbonised data‑centre agenda underscore the tight coupling between AI and electricity. India’s grid already faces stress from rising demand and climate‑induced shocks.

Scaling AI compute without parallel investments in renewables, storage, transmission and perhaps new nuclear could exacerbate both local pollution and global emissions.

Aligning AI growth with climate commitments will demand integrated planning: incentives for green data centres, waste‑heat reuse, location of facilities near renewable‑rich regions and efficiency standards for hardware and software.

On social protection and skills, Altman’s and Hassabis’s timelines for disruptive change in white‑collar work, services and manufacturing call for anticipatory reforms in education and labour policy.

Curricula must integrate AI literacy and critical thinking from school onwards. Mid‑career reskilling, modular online courses and certification schemes will be needed so that workers displaced or transformed by AI‑driven automation can move into new roles.

Debates around income support, unemployment insurance and portable benefits are likely to intensify as AI reshapes employment patterns.

The cause is rapid technical change; the effect could be either managed transition or social unrest, depending on policy responses.

On rights and democracy, Modi’s authenticity labels and Macron’s child‑protection proposals are partial answers to deeper problems.

Comprehensive safeguards will require clear limits on biometric surveillance, strict rules for AI use in policing and welfare, protection for encryption and anonymity in some contexts, and strong remedies for those harmed by automated decisions.

Independent regulators with real authority, judicial oversight and public‑interest litigation will be essential to keep both state and corporate power in check.

On multilateralism, India’s aspiration to steward a global AI commons will be tested in forums such as the United Nations, the Group of twenty and specialised coalitions.

Proposals could include shared compute facilities for low‑income countries, open‑access multilingual datasets, interoperable safety standards, joint incident‑response exercises and agreements on export controls that balance security with development needs.

The cause would be deliberate efforts to widen participation; the effect, if successful, would be an AI order that is less tightly bound to any single bloc.

Conclusion

India’s Summit and the future of global governance

The India AI Impact Summit 2026 is a staging point in the struggle to shape how artificial intelligence is woven into global economic, social and political life.

In New Delhi, five figures crystallized the stakes.

Modi framed AI as a civilisational choice and proposed a MANAV framework to keep it tethered to human welfare.

Pichai offered infrastructure and investment, tying Google’s future closely to India’s AI trajectory.

Altman brought the shock of compressed timelines and the reality of super-intelligence into the room, insisting that access, adoption and agency must be aligned.

Macron advocated for rules, decarbonized power and a “third way” between rival superpowers.

Hassabis described a near future of agentic systems transforming science, while warning that only shared norms can manage systemic risks.

Collectively, these voices reveal both convergence and fracture.

There is broad agreement that AI cannot be left solely to market forces or narrow national interest; some form of governance beyond the firm and beyond the state is needed.

There is also a shared sense that AI’s benefits could be extraordinary, particularly in areas like health, agriculture and climate resilience that matter deeply for the Global South.

Yet there is less agreement on how power, profit and risk should be distributed, and on how much control citizens should have over systems that will increasingly mediate their lives.

For India, the summit has already achieved some goals: it has positioned New Delhi as a central stage for AI diplomacy, attracted significant investment commitments and showcased its digital public‑goods model.

The harder test will be whether India can sustain three roles at once: laboratory for population‑scale AI deployment, advocate for Global South interests and credible rule‑maker in a contested technological order.

Success will require consistent policy, institutional strength and a willingness to tolerate scrutiny and dissent at home.

If those conditions are met, historians may look back on the India AI Impact Summit 2026 as one of the moments when the geography and governance of AI began to shift, however imperfectly, toward a more plural and representative configuration.

If not, the summit will appear as a vivid but fleeting episode in a longer story dominated by a few entrenched powers and platforms.

The speeches in Delhi show that the space for choice is still open.

The choices themselves will unfold in the quieter, slower work of building institutions, writing laws, designing systems and contesting their use long after the cameras leave Bharat Mandapam.