India, Google and AI: New Delhi and Vizag Reshapes Global Digital Power Dynamics - Part V

Executive Summary

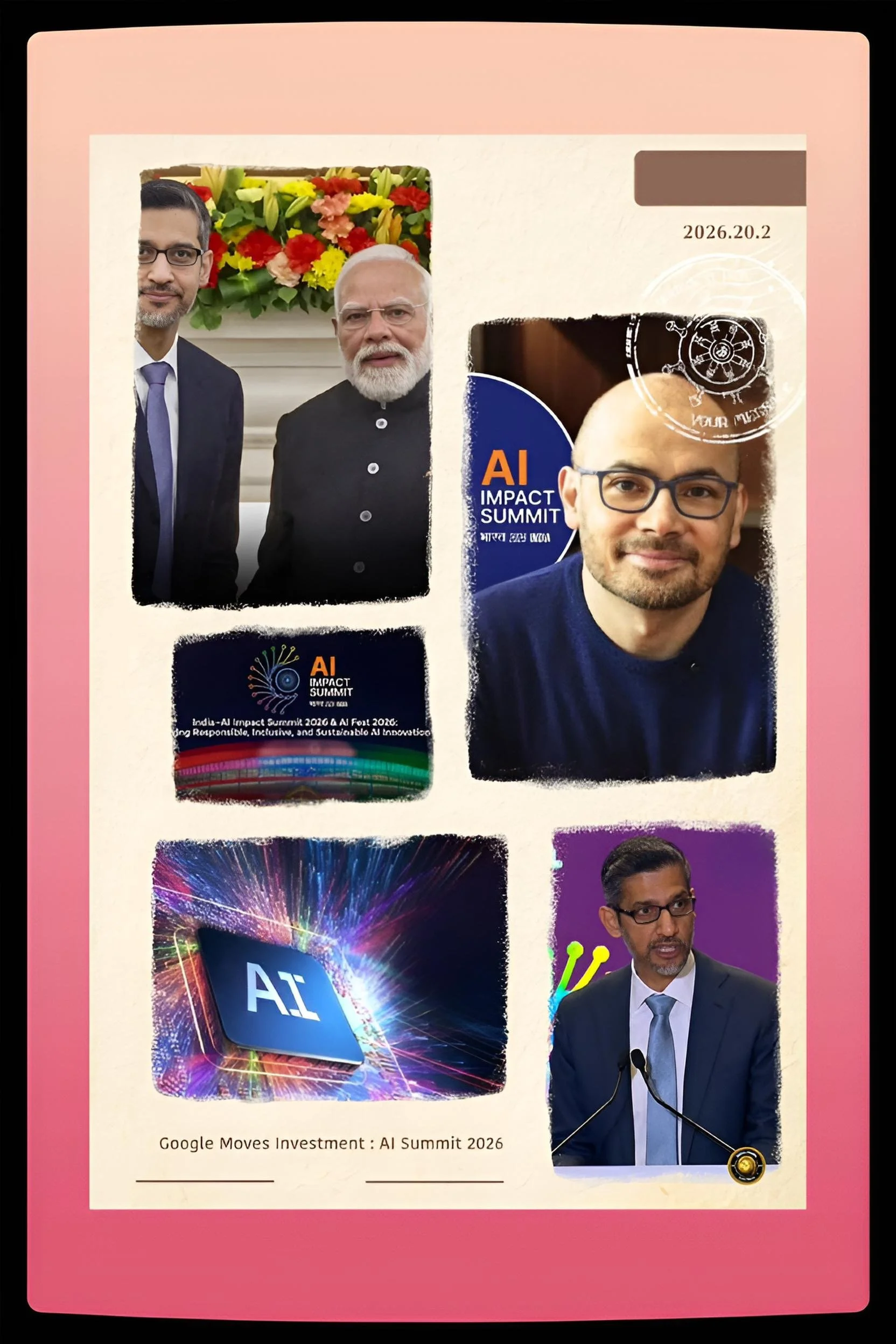

Google, India and the Geopolitics of AI after the India AI Impact Summit

The India AI Impact Summit 2026 in New Delhi represented far more than a technology conference.

It was a stage on which India sought to redefine itself from a peripheral digital services hub into a central architect of the global AI order, and on which Google and Google DeepMind signalled how deeply they intend to anchor their future in India’s political economy.

Sundar Pichai’s announcement of a $15 billion AI hub in Visakhapatnam, coupled with the America–India Connect subsea cable initiative, placed hard infrastructure at the centre of a new strategic compact between India and one of the world’s most powerful technology firms.

Demis Hassabis’s parallel emphasis on AI‑for‑science partnerships, the limits of current systems, and the need for new global governance made clear that frontier AI is now inseparable from questions of national strategy and institutional design.

The summit exposed a set of interlocking dynamics. India’s digital public infrastructure and vast pool of developers position it as a natural testbed and scale market for AI, while its geopolitical posture as a large, non‑aligned democracy makes it an attractive partner for US‑based firms seeking a counterweight to China. Yet India remains deeply dependent on foreign platforms for cloud, models, and high‑end chips, raising concerns in New Delhi about strategic vulnerability and “digital colonialism”.

Pichai’s and Hassabis’s interventions simultaneously deepen that dependency and offer pathways to mitigate it through shared infrastructure, open science, and co‑designed governance.

This essay argues that the summit is best interpreted as an inflection point in the geopolitics of AI. It marked India’s transition from being primarily an arena in which foreign platforms compete to becoming a co‑author of norms, networks, and institutions.

At the same time, it hardened the reality that AI power now rests on control over 3 intertwined assets: compute infrastructure and subsea cables; large‑scale models and data; and convening capacity in global governance forums.

The interplay of these assets will determine whether India becomes a distinct kind of AI superpower—open, pluralistic, and development‑oriented—or a vast but structurally subordinate node in an American‑centred AI ecosystem.

Introduction

Subsea Cables And Code: Google Bets On India’s Future Prosperity

An AI Summit as Strategic Inflection Point

When India agreed to host the AI Impact Summit 2026 at Bharat Mandapam in New Delhi, it did so with a clear political intention.

Earlier high‑level meetings on AI governance had taken place in the UK and South Korea, signalling that advanced industrial democracies claimed ownership over the safety and ethics agenda.

By bringing the summit to India, New Delhi sought to assert that a large Global South democracy must have an equal voice in defining how AI is developed, deployed, and regulated.

Into this theatre stepped Sundar Pichai and Demis Hassabis.

Pichai, who grew up in Chennai and now leads a conglomerate that shapes information flows for billions, embodies the arc from Indian middle‑class aspiration to global digital power.

Hassabis, whose lab delivered landmark breakthroughs such as AlphaGo and AlphaFold, personifies frontier AI research and the long‑term question of artificial general intelligence.

Their decision to deliver coordinated messages in Delhi rather than in Silicon Valley or Washington indicated that they see India not simply as a market, but as a locus of strategic legitimacy.

On stage, Pichai blended developmental rhetoric with strategic calculation.

He praised India’s digital public infrastructure, its start‑up ecosystem, and its capacity to “leapfrog” through AI, but he anchored this optimism in a concrete material commitment: a $15 billion AI hub in Visakhapatnam, backed by gigawatt‑scale data centres and new subsea connectivity.

Hassabis, in turn, used his summit and side‑event interventions to stress that current AI systems are “jagged” in their capabilities, that AGI remains five to eight years away, and that existing institutions are unprepared for the systemic risks that highly capable AI may pose.

Taken together, their remarks framed the summit as both a wager and a warning.

The wager is that India’s combination of scale, democratic legitimacy, and digital experimentation makes it an ideal partner for an American firm determined to remain at the frontier of AI.

The warning is that without credible governance, infrastructural resilience, and shared norms, the rapid diffusion of AI could deepen global inequalities and provoke destabilising forms of technological competition.

History and Current Status

Google, India and the Making of an AI Corridor

To see why this moment matters, one must trace the long co‑evolution of Google’s India strategy and India’s digital statecraft. For most of the 2000s, the relationship followed a familiar pattern: India supplied talent and eyeballs; Google supplied platforms and monetised advertising.

The balance began to shift with the rise of the “India Stack”—a layered architecture of digital ID (Aadhaar), instant payments (UPI), and public platforms that enabled low‑cost, high‑volume digital transactions.

This infrastructure became a global reference point for inclusive digital design. It also forced foreign firms to adapt.

Google Pay, for instance, had to integrate with UPI rather than impose a proprietary payments rail, and Android had to adjust to a regulatory and competitive environment in which domestic apps could ride on public APIs.

For Google, India ceased to be only a monetisation play; it became a laboratory for business models, language technologies, and low‑bandwidth services that could be exported to other emerging markets.

The advent of modern AI supercharged this dynamic. India rapidly became one of the largest user communities for generative AI tools, driven by an English‑speaking professional class and a huge freelance and IT services workforce already comfortable with digital tools.

Surveys highlighted that a high share of office workers in India were experimenting with AI assistants, and usage metrics suggested that Indian users integrated AI into daily workflows more quickly than their counterparts in many richer economies.

At the policy level, New Delhi began to weave AI into its domestic and international agendas. Documents such as the National Strategy for AI and the IndiaAI Mission framed AI as a “force multiplier” for sectors from agriculture to health, with explicit emphasis on inclusion and “AI for All”.

Indian diplomacy, meanwhile, started to position AI alongside digital public infrastructure as an exportable model and a tool of soft power, especially in South Asia and Africa.

These developments unfolded against a widening global AI rivalry.

The US and China poured resources into chips, data centres, and national champion firms, while Europe focused on regulatory frameworks and standards.

Export controls on high‑end semiconductors, restrictions on cross‑border data flows, and competing visions of AI governance turned AI into a core theatre of great‑power competition.

In this emerging landscape, India occupied an ambiguous space: courted by Western firms and governments as a counterweight to China, yet still reliant on foreign platforms, and wary of becoming a mere appendage in someone else’s technology bloc.

By early 2026, India’s AI ecosystem looked simultaneously dynamic and constrained. Public initiatives aimed to expand national compute capacity by adding more than 20,000 GPUs to an existing base of about 38,000, and to make that capacity accessible to researchers and start‑ups through shared facilities.

Domestic firms and consortia released Indian language models and sector‑specific applications, and AI‑enabled services began spreading into education, finance, and agriculture.

Yet the Economic Survey 2025–26 sounded an unusually sharp note of caution, warning that reliance on foreign AI and cloud platforms exposed India to “strategic risks” in an era of technology weaponisation and supply chain fragmentation.

Key Developments at AI Summit

From Back Office To Architect: India’s New AI Strategy Emerging

Against this backdrop, Pichai’s and Hassabis’s interventions at the summit introduced several concrete moves that collectively reshape India’s AI trajectory.

The headline announcement remained the $15 billion AI hub at Visakhapatnam. According to Google’s own description, the hub will consist of hyper‑scale data centres, advanced power infrastructure, and expanded fibre routes, integrated into Google’s global network.

Crucially, it will anchor new subsea cables that make Vizag a key landing point on India’s eastern coast, complementing existing hubs on the western seaboard.

Pichai framed this as a way to create jobs, enable Indian start‑ups to train and deploy large models at lower latency, and support public‑sector AI applications.

The America–India Connect initiative expanded this infrastructural logic beyond India’s shores. The project will lay new subsea cables linking India directly to the US and several points in the southern hemisphere, thereby increasing route diversity and resilience.

In Pichai’s account, this is central to preventing the existing digital divide from ossifying into an AI divide, where only countries with robust connectivity and ample cloud capacity can realistically deploy frontier AI.

For India, it also reduces dependence on a small set of older routes and chokepoints that could, in a crisis, become leverage for adversaries.

On the research and public‑interest front, Hassabis and Pichai announced an intensified partnership between Google DeepMind, Google Research, and Indian institutions.

A dedicated initiative will support AI‑for‑science projects in India, deploying tools such as AlphaFold’s successors, AI Co‑scientist, and new Earth‑system models to accelerate discovery in health, life sciences, climate, and disaster resilience.

This is reinforced by the Google.org Impact Challenge: AI for Science, a $30 million global fund for researchers and organisations using AI to push the boundaries of scientific knowledge, and a separate $30 million AI for Government Innovation Impact Challenge focused on strengthening public‑sector service delivery with AI.

India features prominently in both. Projects such as hyper‑local monsoon forecasting, crop‑yield prediction, and energy‑grid optimisation were highlighted in summit‑related communications as areas where AI models co‑designed with Indian partners could yield outsized benefits.

These scientific and public‑sector collaborations reinforce the narrative that Google’s AI presence in India goes beyond advertising and consumer apps into the core of development and state capacity.

A further pillar of the summit announcements was skills and inclusion. Pichai introduced a Google AI Professional Certificate targeted at millions of learners, with India as a priority market.

The program, delivered through partnerships with local training providers and platforms, aims to build a pipeline of AI‑literate workers for both domestic and global markets.

At the school level, Google committed to expanding its AI‑powered tools across more than 10,000 Atal Tinkering Labs and associated institutions, potentially reaching about 11 million students with AI‑enabled coding and robotics support.

Finally, the summit gave formal shape to a National Partnerships for AI framework between Google DeepMind and India.

Building on similar arrangements with the US and UK, this framework is meant to provide Indian government agencies, universities, and civil‑society actors with “broad access to frontier AI capabilities” for projects in science, education, resilience, and public services.

While details remain sparse, the message is clear: Google DeepMind seeks to position itself not just as a private lab selling products, but as a quasi‑public infrastructure partner embedded in India’s AI governance architecture.

Latest Facts and Concerns

Pichai, Hassabis And Delhi: Inside The Geopolitics Of AI Today

Scale, Dependency, Inequality and Security

The scale and scope of these developments are impressive. They also sharpen several structural concerns that were already visible in Indian policy debates.

First, there is the question of dependency on foreign platforms.

Over the past 2 years, US hyperscalers have announced roughly $52 billion in AI‑linked investments in India, largely in cloud, data centres, and digital infrastructure.

Google’s $15 billion hub adds to this wave, making American firms the dominant owners and operators of the physical and virtual platforms on which much of India’s AI future will run.

While this accelerates capacity, it also raises the spectre of lock‑in: once public agencies, universities, and firms base their workflows and data pipelines on a particular cloud and model stack, switching providers becomes costly and politically difficult.

The Economic Survey’s warning about reliance on foreign AI platforms should be read in this light. It argued that in a world of tightening export controls, sanctions, and techno‑nationalist policies, over‑dependence on overseas infrastructure and models exposes India to extraterritorial shocks.

A single regulatory change in a foreign jurisdiction, a geopolitical dispute, or a corporate decision about content policy could ripple through India’s economy and governance systems if those systems are deeply integrated with foreign AI platforms.

Second, the social distribution of AI benefits remains highly unequal. Despite major gains, broadband connectivity, device ownership, and digital literacy are still uneven across regions, classes, and genders in India.

If the primary beneficiaries of enhanced AI infrastructure and services are urban, English‑speaking professionals and large firms, AI may reinforce existing hierarchies rather than erode them.

Pichai himself acknowledged that without deliberate effort, a digital divide could become an AI divide, with those offline or under‑connected finding themselves further marginalised as more services, from job search to education, assume AI access.

Third, the expansion of AI into governance and security brings new risks of surveillance and control.

As Indian authorities deploy AI for facial recognition, predictive policing, welfare targeting, and content moderation, questions arise about transparency, accountability, and rights protections.

When such systems are built on foreign‑owned models and clouds, the governance challenge is compounded by issues of jurisdiction, data access, and the ability of Indian regulators to audit and constrain algorithms developed abroad.

Fourth, the global risk architecture for AI remains underdeveloped. Hassabis’s observation that AI is digital, borderless, and capable of scaling very quickly implies that national regulation alone will be insufficient to manage systemic risks such as model‑enabled cyberattacks, information manipulation, or bio‑security threats.

While India has positioned itself as a champion of “safe and trusted AI” and an advocate for an “AI commons”, the institutional mechanisms to coordinate standards, share incident data, and enforce constraints across borders are still embryonic.

Finally, there is a concern about what kind of innovation ecosystem will grow under the shadow of large foreign platforms.

If domestic firms and labs primarily build applications on top of closed, proprietary models and clouds, the country may end up specialising in lower‑margin, less strategic segments of the AI value chain, echoing the historical pattern of IT services dependence.

The summit’s emphasis on AI‑for‑science and open collaboration offers one route away from that outcome, but it will require sustained political and financial backing from India to translate potential into independent capability.

Cause‑and‑Effect Analysis

How Google’s India’s Strategy Reshapes AI Power

The causal mechanisms through which the summit’s announcements will shape the geopolitics of AI can be traced across 4 domains: infrastructure, industrial structure, diplomacy, and domestic political economy.

At the infrastructural level, the Visakhapatnam hub and America–India Connect cables alter the topology of global digital networks.

By shifting a significant slice of Google’s AI compute capacity and subsea connectivity to India’s eastern coast, they both harden India’s role as a critical transit and hosting point and make Google itself more reliant on Indian territory and regulation.

This dual dependence creates a feedback loop: as India becomes more central to Google’s operations, Google has a stronger incentive to accommodate Indian policy preferences, while India has a stronger stake in the company’s stability and global standing.

However, infrastructure can generate asymmetric effects. Control over the hardware and cable routes does not automatically translate into control over the software, models, and capital that animate them.

If ownership and governance of the data centres, cloud stack, and AI models remain tightly held by Google entities governed under US law, then even infrastructure located in India may be subject to extraterritorial constraints, including export controls or legal demands from foreign authorities.

In that case, the summit’s infrastructural commitments could deepen India’s exposure to foreign jurisdiction at the same time as they enhance resilience against physical disruptions.

At the level of industrial structure, Google’s deepening presence in India pushes the ecosystem toward a hybrid model.

Frontier models and platform infrastructure are likely to remain concentrated in a handful of US‑headquartered firms, including Google DeepMind.

At the same time, India is seeking to foster its own national‑scale models, open‑source initiatives, and sectoral AI stacks tailored to local needs. If carefully managed, this could produce a layered architecture in which domestic stakeholders retain domain control over critical applications and data, while foreign firms supply general‑purpose capabilities.

Yet there is a risk that the gravitational pull of hyperscaler ecosystems will marginalise domestic alternatives.

The more Indian entities integrate their workflows, data, and talent pipelines into Google’s tools and certifications, the harder it becomes for competing domestic or open‑source solutions to gain traction.

That gravitational effect is reinforced by network externalities: developers and firms prefer to work on platforms where others are already active, and skills acquired through one provider’s certification programs are not always portable.

Diplomatically, the summit strengthens India’s ambition to act as a convening power in AI governance. Hosting global leaders, securing large infrastructure commitments, and articulating themes such as “AI commons” and “AI for All” allow New Delhi to position itself as a bridge between advanced industrial democracies and the wider Global South.

Pichai’s and Hassabis’s high‑profile presence lent credibility to that claim, signalling that frontier firms accept India as a key venue for AI norm‑setting.

However, the same alignment also increases international expectations of India’s own conduct.

Other states will scrutinise Indian policies on issues such as data protection, content takedowns, internet shutdowns, and surveillance as precedents that affect not just domestic users but the integrity of the “AI commons”

India claims to defend. If India’s regulatory behaviour is seen as arbitrary, heavy‑handed, or politically narrow, its ability to lead global debates will weaken, and Google’s partnership may be recast as complicity in illiberal practices.

In domestic political‑economy terms, the summit intensifies existing debates about development, labour, and sovereignty.

On an optimistic trajectory, AI‑enabled productivity gains, better scientific tools, and improved public services could help India escape structural constraints: hyper‑local weather predictions could protect farmers from climate shocks; AI‑assisted diagnostics could extend quality healthcare into rural areas; personalised learning systems could help students in under‑resourced schools.

These are the examples Pichai and Hassabis highlighted to demonstrate that AI can be aligned with human development.

On a pessimistic trajectory, automation could undercut employment in key white‑collar sectors, platform concentration could entrench a handful of firms, and the opacity of AI systems could undermine accountability in governance.

If, in addition, the core infrastructure and models are foreign‑owned, India might find itself in a structurally subordinate position: supplying data and labour while value and control accrue elsewhere.

The summit’s announcements therefore act as accelerants. They amplify the stakes and compress the timeframe within which India must resolve long‑standing tensions between openness and protection, innovation and regulation, partnership and autonomy.

Future Steps

Strategic Choices for India and for Google

In light of these dynamics, future steps for both India and Google will determine whether the summit becomes a foundation for a more balanced AI order or a milestone on the road to deeper dependency.

For India, three tasks stand out. First, it must operationalise the IndiaAI Mission in a way that complements, rather than simply mirrors, the offerings of foreign firms.

That implies directing public funds toward open‑source models for Indian languages, shared compute accessible at subsidised rates to domestic researchers and start‑ups, and the development of interoperable APIs that prevent single‑vendor lock‑in for public systems.

Strategic use of procurement—insisting on open standards, auditability, and data portability in government contracts—can shift bargaining power without resorting to blunt protectionism.

Second, India must align its external diplomacy on AI governance with coherent internal regulation. If it aspires to lead on “safe and trusted AI”, it needs domestic frameworks for safety testing, transparency, and redress that are predictable and rights‑respecting.

That will require legislative clarity on data protection, algorithmic accountability, and platform liability, as well as institutional capacity in regulators to understand and supervise complex AI systems.

Consultation with civil society, academia, and industry will be critical to avoid regulatory capture or over‑correction.

Third, India should weave its AI strategy into broader technology and industrial policies. Initiatives in semiconductors, quantum technologies, and cyber‑security cannot remain siloed if AI is to become a pillar of national power.

For example, aligning semiconductor incentives with AI hardware needs, supporting research into privacy‑preserving and compute‑efficient models, and embedding AI resilience into national cyber‑security doctrines would create reinforcing loops across policy domains.

For Google and Google DeepMind, the primary challenge is to demonstrate that their deepening presence in India enhances rather than erodes India’s autonomy.

This could involve concrete commitments to support open‑source tools for Indic languages, to open certain model components or safety techniques to scrutiny by Indian researchers, and to design data‑handling practices that minimise unnecessary centralisation of sensitive information.

Avoiding exclusivity clauses with public agencies and universities, and enabling easy migration of workloads to other clouds, would signal confidence rather than dominance.

Google DeepMind’s National Partnerships for AI must avoid becoming vehicles for privileged access.

Instead, they should include transparent selection criteria, shared governance boards with Indian representation, and capacity‑building that enables local institutions to develop their own specialised models over time.

In high‑stakes domains such as health, education, and public security, joint oversight mechanisms involving independent experts and civil‑society voices could help legitimise deployments and reduce the risk of technology being used in ways that undermine rights.

At the global level, Pichai and Hassabis can lend weight to efforts to build realistic, multi‑stakeholder AI governance.

Their public recognition that existing institutions are ill‑suited to handle AI’s pace and scale places a responsibility on their firms not to exploit that institutional lag.

Supporting inclusive forums where emerging economies, not only Western governments and corporations, shape baseline safety standards and incident‑reporting mechanisms would align with India’s diplomatic priorities and help distribute authority more fairly.

Conclusion

Will India be an Architect or an Arena?

The India AI Impact Summit crystallised a profound shift in the geography of AI power.

By hosting the summit, securing massive infrastructure commitments, and giving the stage to figures like Pichai and Hassabis, India announced its intention to move from the margins of AI geopolitics toward its centre. Google and Google DeepMind, for their part, acknowledged that the future of their business and research is inseparable from the choices made in places like New Delhi and Visakhapatnam.

Yet the summit also underscored that AI power is not a binary condition. It is a spectrum structured by control over networks, models, norms, and narratives. India has clear assets: demographic scale, digital public infrastructure, a vibrant developer base, and growing diplomatic clout.

Google has capital, technical leadership, and global reach. Together, they can help shape a world in which AI serves as an instrument of inclusive development and pluralistic governance rather than of surveillance capitalism or authoritarian control.

Whether that world comes into being depends on the political decisions now confronting both sides. If India insists on openness, accountability, and genuine capacity‑building in its partnerships, and if Google accepts constraints as the price of long‑term legitimacy, the relationship forged at the summit could anchor a more balanced AI order.

If, instead, infrastructure and rhetoric mask a deepening asymmetry of control over code, compute, and data, the summit will be remembered as the moment when a new form of dependency was dressed up as empowerment.

The central question, then, is whether India will act primarily as an arena in which external actors compete for influence, or as an architect of institutions, infrastructures, and ideas that redefine the terms of that competition.

The India AI Impact Summit, and the roles played by Sundar Pichai and Demis Hassabis within it, have moved India closer to the latter role.

The durability of that shift, however, will be measured not in summit communiqués, but in the concrete architectures of power that emerge across India’s clouds, cables, laboratories, and laws in the decade to come.