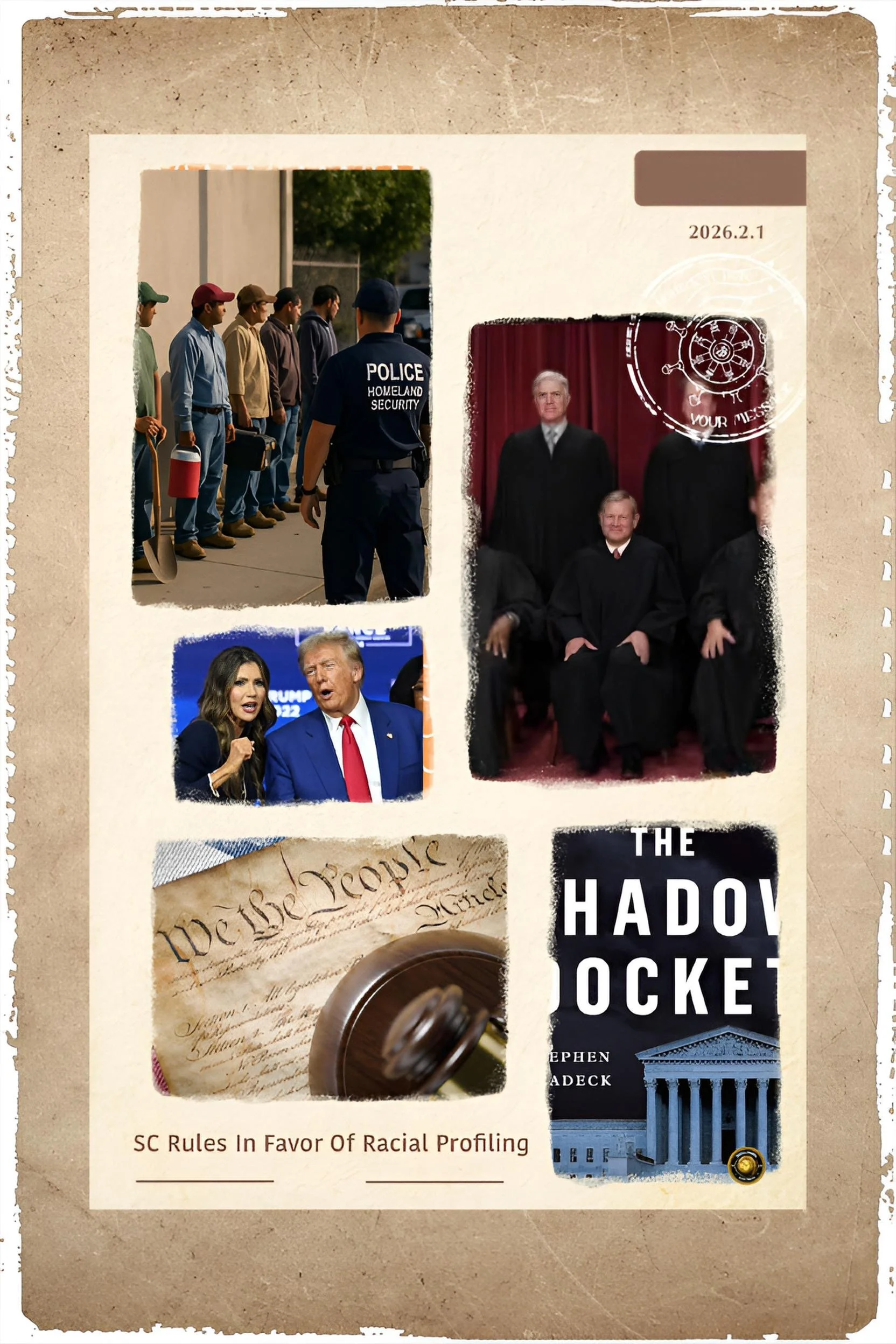

The Supreme Court's Shadow Docket and the Erosion of Fourth Amendment Protections: Analyzing Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo

Executive Summary

On September 8, 2025, the United States Supreme Court issued an unsigned, non-reasoned decision lifting a district court's temporary restraining order that had enjoined Immigration and Customs Enforcement from conducting investigative stops premised upon what the lower court determined were patently unconstitutional criteria.

The 6-3 decision, denominated Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo and resolved through the Court's emergency or "shadow" docket, effectively ratified discriminatory enforcement practices without issuing a majority opinion articulating constitutional justification.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh's solo concurrence—the decision's only published reasoning—provided substantive support for immigration enforcement predicated upon apparent ethnicity, linguistic markers, employment categories, and geographic location, thereby establishing what jurists and legal commentators subsequently designated as the "Kavanaugh stop" doctrine.

FAF analysis examines the institutional, constitutional, and evidentiary foundations of the Court's decision, its doctrinal tensions with contemporaneous Supreme Court precedent, and the consequences for Fourth Amendment protections and equal protection guarantees.

Introduction

The Shadow Docket and Emergency Decisional Authority

The Supreme Court possesses plenary authority to grant stays of lower court injunctions pending appellate review through what is formally denominated emergency jurisdiction or, colloquially, the "shadow docket."

This discretionary authority permits the Court to issue unsigned, unreasoned orders resolving novel and complex constitutional questions without full briefing, oral arguments, or the deliberative processes conventionally attendant to the Court's merits docket.

While the shadow docket historically functioned for narrow procedural or manifestly uncontroversial matters, institutional analysts—including former Supreme Court clerks and constitutional law scholars—have documented a systematic expansion of shadow docket authority for substantively significant and doctrinally novel questions, particularly during the Trump administration.

Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo exemplifies this institutional phenomenon.

The case originated from Immigration and Customs Enforcement operations occurring in June 2025 throughout the Central District of California, encompassing Los Angeles, Ventura, Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo, Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino Counties.

Beginning in July, ICE conducted what agency officials characterized as "Operation at Large"—roving enforcement patrols targeting individuals for immigration status investigation.

By July 11, 2025, a putative class of plaintiffs and identified victims of prior enforcement encounters initiated litigation seeking preliminary injunctive relief against the agency's enforcement practices.

The district court, presided over by Judge Maame Ewusi-Mensah Frimpong, determined that constitutional violations were sufficiently probable and irreparable harm sufficiently manifest to warrant a preliminary injunction.

History and Current Status

The District Court's Factual Findings and Constitutional Analysis

Judge Frimpong's July 11, 2025, order issued a temporary restraining order enjoining ICE from continuing "Operation at Large" enforcement activities absent independent reasonable suspicion of immigration law violations.

The order emerged from extensive factual findings regarding ICE's enforcement methodology. The court determined, based on documentary evidence and witness testimony, that ICE agents had conducted investigative stops and arrests exclusively or predominantly upon 4 enumerated factors:

(1) Apparent race or ethnicity

(2) Speech patterns, including Spanish language usage or accented English

(3) Presence in geographic locations where undocumented immigrants reportedly congregated, including day labor pickup sites, car washes, residential complexes with immigrant populations, and transit hubs

(4) Employment in industries historically associated with undocumented labor, including landscaping, construction, agriculture, and day labor.

Critically, the Government submitted no evidentiary materials suggesting that investigative stops were predicated upon factors other than these 4 criteria.

The court documented "ample evidence that seizures occurred based solely upon the four enumerated factors, either alone or in combination." Furthermore, the court identified "a plethora of statements suggesting approval or authorization" of the Government's pattern of reliance upon these factors, creating a heightened likelihood of recurrent conduct.

The court's Fourth Amendment analysis proceeded from the principle that the Fourth Amendment's prohibition on unreasonable seizures applies with equal force to immigration investigations as to criminal law enforcement.

The Constitution does not establish immigration exceptionalism, permitting seizures lacking reasonable suspicion.

Consequently, the government's systematic reliance on race, ethnicity, language, and employment categorization as determinative factors in investigative stops violated the Fourth Amendment's foundational requirement that seizures rest on individualized reasonable suspicion of a criminal or immigration violation.

Key Developments

The Government's Appeal and Supreme Court Intervention

Upon issuance of the district court's TRO, the Trump administration initiated expedited appellate proceedings in the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

The Ninth Circuit panel, in an August 1 per curiam opinion applying the 4-factor standard established in Winter v. Natural Resources Defense Council, denied the Government's motion to stay the TRO pending appeal.

The panel concluded that the Government had failed to demonstrate either a substantial likelihood of success on the merits or that the balance of equities favored issuance of a stay.

The Government then filed an emergency application for a stay with the Supreme Court.

The application, filed August 7, 2025, argued that the district court's injunction erred in multiple respects: first, that the plaintiffs lacked Article III standing to seek broad injunctive relief; second, that the stops comported with Fourth Amendment precedent permitting consideration of multiple factors in determining reasonable suspicion; and third, that the injunction was overbroad in restricting enforcement throughout the Central District of California rather than remaining limited to named plaintiffs.

On September 8, 2025—precisely 1 month after the district court issued the TRO—the Supreme Court granted the Government's motion for stay.

The decision was issued without an accompanying majority opinion, meaning the Court did not articulate its constitutional reasoning or legal principles.

The vote was 6-3, with the apparent 6-justice conservative bloc voting to grant the stay, and Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson dissenting.

Latest Facts and Concerns

Justice Kavanaugh's Concurrence and Doctrinal Framework

Only Justice Brett Kavanaugh issued a published opinion accompanying the stay decision. His 10-page concurrence constitutes the sole official exposition of reasoning underlying the 6-3 majority. Kavanaugh addressed three dimensions: standing, Fourth Amendment doctrine, and the balance of equities.

On standing, Kavanaugh contended that the plaintiffs had not demonstrated the requisite likelihood of recurrent injury.

Specifically, he argued that plaintiffs could not establish that future ICE enforcement would replicate the pattern of discrimination the district court had documented.

This standing argument presented substantial doctrinal difficulty, as established precedent—particularly the Supreme Court's decision in Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife—permits organizational plaintiffs to establish standing based on a reasonable probability that organizational activities will impose recurrent injury upon organization members. Kavanaugh did not directly grapple with this precedent.

On the Fourth Amendment doctrine, Kavanaugh emphasized that immigration enforcement differs constitutionally from criminal law enforcement.

Immigration officers, he asserted, may conduct investigative stops based on a lower threshold than criminal law enforcement's "reasonable suspicion" requirement.

He quoted United States v. Brignoni-Ponce (1975), a case addressing Border Patrol checkpoint stops, for the proposition that law enforcement officers may consider "any number of factors," including apparent ethnicity, when assessing whether reasonable suspicion exists.

Kavanaugh then elaborated: in regions with high percentages of undocumented immigrants (citing estimates of 1-12 million nationally, with approximately 85 percent originating from Mexico or Central America), immigration officers could constitutionally consider as part of the reasonable suspicion calculus-

(1) The high number and percentage of undocumented immigrants residing in the region

(2) The tendency of undocumented immigrants to "gather in certain locations."

(3) Their tendency to "often work in certain kinds of jobs, such as day labor, landscaping, agriculture, and construction" because these "do not require paperwork."

(4) The fact that many "do not speak much English."

(5) "Apparent ethnicity."

He concluded: "To conclude otherwise, this Court would likely have to overrule or significantly narrow two separate lines of precedents" regarding immigration enforcement and Fourth Amendment doctrine. Kavanaugh conceded that "apparent ethnicity alone cannot furnish reasonable suspicion" but maintained that ethnicity qualifies as a "relevant factor when considered along with other salient factors."

Finally, Kavanaugh addressed equities by emphasizing that any inconvenience to lawful residents or citizens from investigative stops would be minimal: "immigration officers may briefly stop the individual and inquire about immigration status. If the person is a U.S. citizen or otherwise lawfully in the United States, that individual will be free to go after the brief encounter."

He further diminished the interests of undocumented immigrants themselves, characterizing their concern as "evasion of detection by law enforcement," thereby rendering their "weighty" legal interests comparatively modest.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis

Constitutional Contradictions and Institutional Implications

The Noem decision creates profound doctrinal tension with contemporaneous Supreme Court precedent and raises institutional questions about judicial consistency in racial discrimination doctrine.

First, constitutional incoherence on race and discrimination is forcefully evident.

In Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard (2023), the Supreme Court prohibited consideration of race in university admissions, with Chief Justice John Roberts authoring: "Eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it." The Court grounded this principle in the equal protection doctrine, establishing that government institutions must maintain race-neutral policies.

Yet in Noem—decided approximately 2 years after Students for Fair Admissions—the Court countenances immigration enforcement explicitly incorporating apparent ethnicity as a factor in seizure determinations.

The logical inconsistency is manifest: if race-conscious admissions policies in higher education violate the Equal Protection Clause because they "discriminate based on race," how does considering race as a factor in immigration enforcement comply with Fourth Amendment principles or Equal Protection requirements? Kavanaugh's response—that ethnicity is merely one of multiple factors—fails as distinguishing logic.

In Students for Fair Admissions, the Court rejected this "one factor precisely among many" rationale for race-conscious decision-making.

Second, evidentiary problems undermine the decision's jurisprudential foundation.

The district court found that the Government submitted "no evidence suggesting that its seizures to date were based on anything other than" the 4 profiling factors. Subsequently, after Judge Frimpong issued the July 11 injunction, ICE arrests in Los Angeles County declined precipitously by 66%.

This data point is remarkable: if the 4 factors (race, ethnicity, language, location, employment) were merely peripheral considerations in ICE's reasonable suspicion determinations, one would expect enforcement levels to remain substantially constant following the restriction on their use.

Conversely, the 66% reduction in arrests directly demonstrates that these factors were decisive in ICE's enforcement decisions.

The Ninth Circuit panel and the district court both explicitly noted this evidentiary record, yet the Supreme Court issued its stay without a written explanation and proceeded regardless.

Third, institutional consequences emerge from the shadow docket mechanism itself. By issuing an unsigned, unreasoned decision, the Supreme Court avoided articulating precedential principles and acknowledged no logical tensions with Students for Fair Admissions.

Lower courts lack guidance regarding the decision's analytical basis and scope.

Law enforcement agencies nationwide interpreted the decision expansively, as authorizing race- and ethnicity-based stops across jurisdictions.

Advocates and legal commentators, lacking official reasoning, engaged in interpretive construction of Kavanaugh's concurrence as the decision's intellectual foundation—a role for which a concurring opinion was never designed.

Fourth, the standing doctrine is strained.

Kavanaugh contended that plaintiffs failed to demonstrate the "likelihood of recurrence" necessary for standing. Yet the district court had made affirmative findings of "high likelihood of recurrent injury" and noted "plethora of statements suggest[ing] approval or authorization" of continuing enforcement patterns.

The precedential framework established in cases such as City of Los Angeles v. Lyons articulates that organizational plaintiffs need not demonstrate absolute certainty of recurrence, only reasonable probability. The district court's findings substantially satisfied this standard.

Fifth, the Fourth Amendment doctrine articulated in Noem represents a significant departure from criminal law enforcement standards.

The decision essentially creates immigration-specific constitutional doctrine permitting investigative seizures predicated upon factors—apparent ethnicity, language, employment type—that would violate Fourth Amendment principles in criminal contexts.

If a municipal police department conducted traffic stops based on "apparent ethnicity," "Spanish language usage," and "type of employment," courts would likely invalidate such practices as violating Fourth Amendment guarantees and Equal Protection principles. Yet immigration enforcement receives heightened constitutional deference.

The practical consequence: the decision ratifies what scholars denominate "profiling by proxy." Rather than explicitly using race as the determinative factor (which Kavanaugh acknowledges cannot, standing alone, establish reasonable suspicion), ICE employs multiple racially-correlated factors—language, employment, location—whose cumulative effect targets ethnic minorities systematically.

Future Steps

Institutional and Constitutional Remedies

Restoring Fourth Amendment coherence and equal protection guarantees necessitates multiple institutional and legal interventions.

At the immediate level, litigation in lower courts continues regarding Noem's scope and application. Several district courts have begun distinguishing Noem's holding, noting that Kavanaugh's concurrence articulated narrow principles specific to border regions or areas with high undocumented populations.

Other courts have attempted to preserve the requirement that ethnicity not constitute a "determinative" factor, even if it qualifies as one element.

Legislative intervention offers a substantive remedy.

Congress could enact statutes explicitly prohibiting immigration officers from considering apparent race, ethnicity, or language in investigative determinations, thereby overriding executive enforcement discretion and establishing statutory Fourth Amendment protections exceeding constitutional minimums.

The "Stop Excessive Force in Immigration Act," proposed by Senators Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly, includes provisions addressing investigative stop standards. However, such legislation faced opposition in the Republican-controlled Congress.

Constitutional litigation pursuing declaratory judgment or injunctive relief in venues with more favorable precedential frameworks remains available.

Some federal circuits—particularly the Ninth Circuit, which had denied the Government's stay motion—retain greater skepticism regarding immigration exceptionalism.

International human rights mechanisms, while non-binding domestically, provide external accountability.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has issued statements characterizing systematic ethnic profiling in immigration enforcement as violating international human rights law.

Documentation by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch establishes patterns of discriminatory enforcement that may constitute human rights violations under international law.

The Supreme Court itself may revisit the question when formal merits briefing concludes in Noem. However, given the 6-3 ideological alignment and Kavanaugh's apparent commitment to immigration-enforcement prerogatives, reversal appears unlikely absent significant doctrinal recalibration or a judicial vacancy.

Conclusion

Democratic Governance and Constitutional Degradation

Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo represents a watershed moment in American constitutional doctrine regarding equal protection, Fourth Amendment guarantees, and the institutional role of the judiciary in constraining executive enforcement discretion.

The decision, reached through the constitutionally attenuated shadow docket mechanism and resting on Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence articulating immigration exceptionalism, effectively ratified discrimination-laden enforcement practices without rigorous constitutional analysis.

The logical tensions with Students for Fair Admissions remain unresolved.

The evidentiary record demonstrating that profiling factors were decisive in 66% of arrests received no acknowledgment.

The standing doctrine was applied in tension with established precedent. The doctrinal framework created what commentators term "profiling by proxy"—systematic racial targeting through facially neutral factors.

The institutional implications extend beyond immigration enforcement.

The shadow docket's utilization for substantively significant constitutional questions circumvents deliberative processes and public accountability inherent in the merits docket. Emergency authority, originally conceived for narrow procedural matters, became instrumentalized for doctrinal innovation.

The consequence: the Supreme Court altered constitutional law regarding Fourth Amendment protections and equal protection guarantees without the deliberative rigor or reasoned explanation expected of the nation's highest judicial institution.

Whether Noem represents constitutional precedent or merely a shadow docket order with limited binding force remains contested. Lower courts continue grappling with appropriate application.

The question looms whether American constitutionalism can sustain a doctrinal framework simultaneously prohibiting racial discrimination in education while permitting race-based investigative stops in immigration enforcement.

That contradiction, unresolved and unexamined in Noem, poses an enduring challenge to constitutional coherence and equal protection principles.