From Nuremberg to 2026: Institutional Capture 2025: How Ambitious Leaders Systematically Dismantle Democratic Checks - Part III

Executive Summary

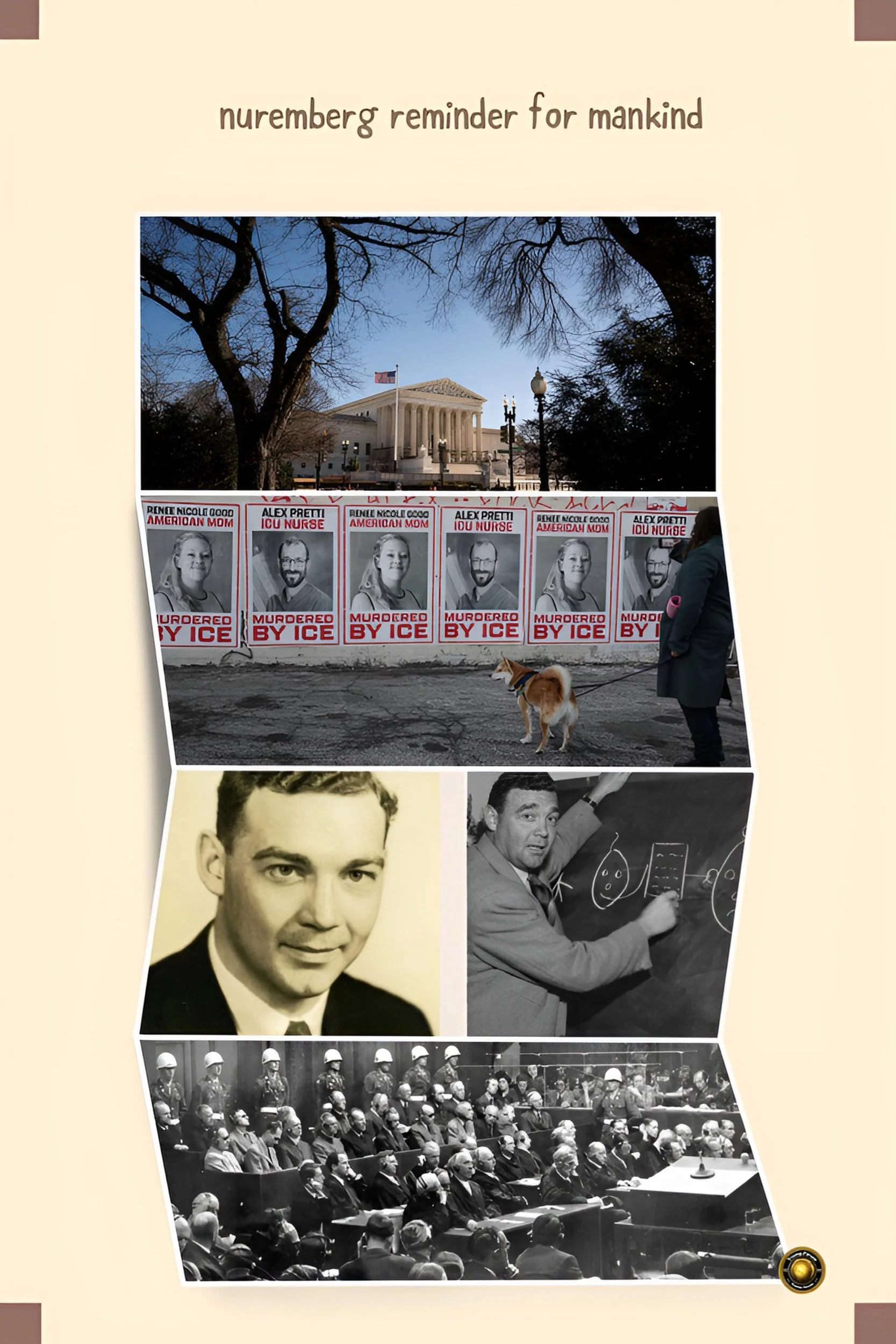

The Supreme Court's September 8, 2025, decision in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo—permitting immigration enforcement predicated upon apparent ethnicity, linguistic markers, and employment categorization—represents a watershed institutional moment whose historical antecedents trace directly to the Nuremberg trials and Douglas Kelley's psychological assessment of Nazi leadership.

FAF's comprehensive analysis applies the frameworks established by Kelley's post-war psychiatric evaluation and Jack El-Hai's historical warnings regarding ordinary ambitious climbers to contemporary institutional dynamics, demonstrating that the convergence of judicial deference, legislative subordination, and bureaucratic normalization constitutes the identical institutional capture mechanism through which Hannah Arendt's "banality of evil" operates.

The decision itself—issued without majority opinion through the shadow docket—exemplifies the procedural mechanisms through which constitutional protections erode without explicit constitutional amendment, mirroring the incremental institutionalization of Nazi racial policy between 1933 and 1935.

This analysis contends that Noem represents not an aberration but a manifestation of institutional dynamics Kelley identified as endemic to democracies insufficiently vigilant against ambitious actors capable of weaponizing governmental apparatus.

Introduction

Kelley's Warning Applied to 2026

Army psychiatrist Douglas M. Kelley returned from Nuremberg in 1946 having completed 5 months of intensive psychological evaluation of 22 senior Nazi officials, including Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, and Wilhelm Keitel.

His conclusion—revolutionary in 1946 and prescient in 2026—diverged fundamentally from prevailing assumptions about Nazi perpetrators. Contrary to contemporaneous belief that Nazi leaders possessed unique psychological pathology or exceptional malevolence, Kelley determined that the defendants represented "ambitious climbers, eager for power and influence and skilled at tugging at the emotions and fears of others to get what they wanted."

These were not madmen or aberrations but rather ordinary individuals whose personality types could be "duplicated in any country of the world today." Critically, Kelley extended his analysis beyond Nuremberg, warning that American democracy faced existential vulnerability to precisely such actors if institutional checks weakened and voters became habituated to emotional manipulation and norm erosion.

Kelley identified 5 distinguishing characteristics of what El-Hai terms the "climber" personality:

(1) Willingness to exploit racial or ethnic categories to consolidate power

(2) Use of emotionally volatile issues—immigration, morality, rights—as wedges to separate constituencies

(3) Installation of loyalists throughout institutions to subordinate institutional integrity to personal/political objectives

(4) Normalization of transgression through procedural legitimacy and administrative necessity arguments

(5) Systematic erosion of institutional checks—judicial, legislative, bureaucratic—that constrain executive prerogative.

Kelley's analysis, delivered during the 1940s, predated contemporary institutional theory by decades yet articulated precisely the dynamics observable in American governance in 2025-2026.

History and Current Status

From Nuremberg Principles to Shadow Docket Precedent

The Nuremberg trials (1945-1949) established foundational principles subsequently codified in international law:

(1) Superior orders constitute no defense for unlawful conduct

(2) Individuals bear personal responsibility for perpetrating atrocity regardless of institutional rank or procedural legitimacy

(3) Institutional position does not exempt officials from accountability for systemic abuse. These principles emerged directly from examination of how ordinary bureaucrats—transportation ministry officials, police commanders, administrative personnel—perpetrated atrocity not through extraordinary malevolence but through thoughtless compliance with institutional directives.

As Hannah Arendt subsequently observed during the Eichmann trial (1961), evil operated through banality—through ordinary people performing mundane administrative tasks within bureaucratic systems that distributed moral responsibility across sufficiently large numbers of actors that no individual felt personally culpable.

The legal doctrine established at Nuremberg explicitly rejected the "following orders" defense. Wilhelm Keitel, Alfred Jodl, and other defendants attempted to argue that they possessed no discretion but to obey Hitler's commands pursuant to the Führerprinzip (leader principle) and military oath.

The tribunal found such arguments unconvincing: officials were responsible for exercising independent judgment regarding the legal and constitutional constraints on orders, irrespective of superior authority.

This doctrine—termed the Nuremberg Principle—became foundational to international criminal law and subsequent human rights frameworks, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court (1998).

The contemporary American immigration enforcement apparatus, as reconstituted between January and September 2025, represents a systematic dismantling of precisely these accountability mechanisms.

The Supreme Court's decision in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo—lifting a federal judge's injunction against ICE enforcement predicated upon racial profiling—inverts Nuremberg principles by validating bureaucratic discretion exercised through racial categorization, whilst simultaneously denying lower courts authority to enforce constitutional constraints.

Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence, the only published reasoning accompanying the 6-3 unsigned decision, explicitly argues that ethnicity qualifies as a "relevant factor" in determining reasonable suspicion for immigration stops.

This constitutes a direct contradiction of the principle established at Nuremberg: that institutional actors cannot hide behind administrative necessity or procedural legitimacy to justify discrimination.

Key Developments

The Institutional Capture Mechanism, 2025-2026

The erosion of Nuremberg-principle accountability proceeded through 4 concatenated institutional mechanisms operationalized across 2025 and early 2026.

First, judicial subordination through personnel replacement and doctrinal reorientation.

The Trump administration appointed 3 Supreme Court justices (Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett), establishing a 6-3 conservative supermajority inclined toward maximalist constructions of executive authority over immigration.

Cumulatively, the administration appointed over 200 federal judges during its 2017-2021 tenure and accelerated the appointment of loyalists during its 2025-2026 tenure.

Concurrently, the Supreme Court embraced the "shadow docket"—unsigned, unreasoned emergency orders—to resolve substantive constitutional questions without deliberation or written opinion.

The Noem decision exemplifies this mechanism: 6 justices voted to overturn a lower court's civil rights judgment without articulating constitutional reasoning, issuing no majority opinion, and offering no guidance to lower courts regarding the decision's scope.

This procedural mechanism effectively removed the constraint that Nuremberg established: the requirement of articulated reasoning subject to public and professional scrutiny.

Second, legislative subordination through executive order authority. On February 24, 2025, the Trump administration issued an executive order subordinating "independent" regulatory agencies to White House oversight through the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA).

This effectively reversed structural constraints established since the Progressive Era (1901-1920) that created independent agencies precisely to constrain executive prerogative. The order enabled the White House to dictate operations, budgetary allocations, and regulatory content of agencies nominally independent.

Simultaneously, Congress—while retaining appropriations authority—faced strategic difficulties in constraining executive action through emergency declarations, previously invoked to bypass congressionally established priorities.

The result: legislative power, though theoretically extant, became practically attenuated.

Third, administrative normalization through Schedule F reclassification and personnel replacement. The administration reclassified civil service positions as "Schedule F" (at-will employment), eliminating protections enabling career officials to resist unlawful directives.

This mechanism—drawn from historical precedent in authoritarian systems—enables wholesale replacement of institutional bureaucrats with loyalists irrespective of qualifications or experience.

Applied to immigration courts, this reclassification enabled the administration to fire immigration judges deemed insufficiently supportive of expedited removal policies.

Career officials representing institutional memory, professional standards, and constitutional commitment could be summarily dismissed.

The mechanism distributes responsibility across institutional actors: each loyalist claims merely to follow orders; each removed official cannot constrain the successor—accountability fragments.

Fourth, judicial deference through doctrinal reordering. Lower courts, recognizing that appellate reversal awaited any civil rights protective decision, increasingly deferred to executive immigration authority.

Federal judges noted this dynamic explicitly. Judge Donovan Frank (Minnesota) documented that ICE routinely "races detainees" to states with more favorable judicial precedent. Judge Patrick Schiltz documented 96 court order violations by ICE in January 2026 alone.

Yet judges lacked enforcement mechanisms: ICE directors refused to enforce contempt proceedings, appellate courts stayed injunctions, and the Supreme Court offered no guidance to constrain executive behavior.

Facing systematic noncompliance and appellate reversals, district judges had to choose between issuing orders that would be violated or capitulating preemptively.

This mechanism—judicial deference wrought through institutional powerlessness—represents a precise inversion of Nuremberg's constraint: judges now shield officials from accountability rather than enforcing it.

Latest Facts and Concerns

The Specific Mechanisms of Institutional Evil

The Noem decision operationalizes institutional evil through 6 specific mechanisms Kelley identified as endemic to authoritarian consolidation.

First, dehumanization through administrative reclassification. In July 2025, ICE issued an internal memorandum reclassifying all undocumented immigrants as "arriving aliens" irrespective of whether they had resided in the United States for years or decades.

This administrative reclassification—semantically trivial but consequentially catastrophic—automatically subjected this population to mandatory detention without judicial discretion.

Historical precedent demonstrates the lethality of such reclassification: Nazi administrative officials achieved ghetto confinement and, subsequently, extermination through reclassification of Jews as "arrivals" ineligible for standard legal protections.

The semantic shift from "resident undocumented immigrant" to "arriving alien" enabled bureaucratic systems to treat this population as transient, outside normal constitutional protection.

Second, normalization of discrimination through procedural legitimacy. Justice Kavanaugh's concurrence articulated the precise argument Kelley warned against: that administrative necessity justifies discrimination if framed as one factor among many.

Kavanaugh argued that in regions with high percentages of undocumented immigrants (1-12 million nationally, 85 percent from Mexico/Central America), immigration officers could constitutionally consider as part of reasonable suspicion: ethnicity, language, employment type, and location.

This argument succeeds precisely because it claims procedural objectivity ("one factor among many") whilst achieving a discriminatory effect (a 66% reduction in arrests when ethnicity-based profiling was prohibited).

The mechanism: distribute decision-making across multiple officers, each claiming to exercise legitimate judgment, such that no individual officer perceives themselves as perpetrating discrimination.

Arendt identified this as the core of administrative evil: fragmented responsibility across sufficiently large bureaucratic systems that individual actors need not confront the moral weight of aggregate consequences.

Third, institutional capture through loyalist installation. The Trump administration expanded the ICE workforce by 120% while simultaneously issuing explicit directives that agents prioritize arrests and detention volumes over legal compliance.

Senior DHS leadership explicitly framed the role of immigration enforcement as a tool for executive political objectives rather than neutral justice administration.

This constitutes a direct Kelley warning: the installation of operatives whose primary loyalty extends to executive authority rather than to institutional integrity. Career officials resisting unlawful directives could be replaced through Schedule F reclassification.

The result: institutional apparatus transformed from constraint on executive action into instrument of executive prerogative.

Fourth, elimination of judicial constraint through appellate authority. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, in an August 1 per curiam opinion, denied the government's motion to stay the district court's temporary restraining order on ICE profiling.

The Supreme Court then issued unsigned stay order on September 8, 2025—precisely 1 month later—overruling the Ninth Circuit without written explanation. This mechanism—appellate reversal through unsigned emergency order—exemplifies Kelley's insight: institutional actors can circumvent normal deliberation through procedural mechanisms.

The Supreme Court's refusal to articulate reasoning prevented lower courts from understanding the decision's doctrinal scope, deterring further protective rulings. One federal judge noted: the Supreme Court "essentially told us not to bother."

Fifth, obstruction of external accountability through information restriction. Beginning January 2026, the Trump administration denied congressmembers access to ICE detention facilities, concealing detainee locations from legislative oversight.

Congressional investigators filed emergency lawsuit seeking restoration of oversight authority. Federal judge refused intervention, ruling that Congress lacked judicially-enforceable right to facility access.

This mechanism—obstruction of oversight through justiciability doctrines—exemplifies how law itself becomes weaponized. Formal law permits congressional oversight; procedural law prevents judicial enforcement of that right. The system collapses from within.

Sixth, violence normalization through state apparatus. During protest actions, ICE agents pepper-sprayed peaceful protesters and legal observers. Federal judge Kate Menendez issued preliminary injunction restricting such violence. Appellate court stayed the injunction. Agents continued violence.

This cycle—judicial order, appellate stay, continued violation—demonstrates the mechanism Kelley warned of: bureaucratic apparatus becomes instrument of state violence when accountability mechanisms fail.

32 deaths occurred in ICE custody during 2025; torture allegations emerged from detained individuals; violence became normalized as operational necessity.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis

From Nuremberg Principle to Institutional Collapse

The causal chain from Nuremberg principles to contemporary institutional collapse operates through sequential erosion of accountability mechanisms.

Nuremberg established that institutional actors bear personal responsibility for systemic abuse irrespective of superior orders or procedural legitimacy. This principle created deterrent effect: officials understood that institutional position provided no shield from accountability.

By contrast, contemporary immigration enforcement operates under presumption of immunity: ICE officials violate court orders without consequence; judges lack enforcement mechanisms; appellate courts reverse protective decisions without explanation; congressional oversight faces procedural barriers.

The mechanism operates through what Arendt termed "the banality of evil": distribution of responsibility across bureaucratic actors such that no individual experiences themselves as perpetrator. An immigration officer conducting a stop "justified" by appearance and language claims mere enforcement of administrative guidance.

The ICE director claims implementation of executive policy. The judge applying Noem precedent claims adherence to supreme judicial authority. The bureaucrat processing expedited removal claims mechanical application of statute. No individual perceives themselves as perpetrating injustice; yet aggregate effect constitutes systematic discrimination.

This mechanism differs fundamentally from overt authoritarianism. A dictator explicitly ordering genocide bears obvious responsibility. By contrast, distributed bureaucratic systems enable ordinary people to perpetrate extraordinary evil whilst maintaining psychological and institutional distance from consequences.

This distinction proves critical: Nuremberg-era accountability mechanisms target explicit orders and command responsibility. Contemporary institutional evil operates through layered bureaucratic systems that fragment responsibility below the threshold of individual culpability.

Kelley specifically warned of this dynamic. Nazi officials did not perceive themselves as perpetrating Holocaust.

Rather, transportation ministry officials transported populations per orders; administrative officials processed deportations per statute; police commanders arrested per directive; camp administrators implemented per procedure.

Each ‘in charge’ performed their function within institutional parameters. Kelley's insight: such stakeholder exist in abundance everywhere, not uniquely in Germany.

The precondition for institutionalized evil is not unique pathology but rather bureaucratic systems that fragment responsibility, institutional capture that eliminates oversight, and psychological processes that permit ordinary people to participate in systemic evil whilst maintaining self-conception as decent people merely following procedures.

The Supreme Court's Noem decision accelerates this dynamic precisely through its procedural mechanism.

(1) By refusing to articulate reasoning, the Court prevented lower courts from developing countervailing doctrine.

(2) By issuing unsigned decision through emergency docket, the Court avoided public deliberation and media scrutiny.

(3) By deferring to executive immigration authority, the Court permitted administrative elaboration of profiling standards without subsequent review.

The result: lower courts, lacking guidance and facing appellate reversal, capitulated. Administrative systems expanded without institutional check.

Future Steps

Restoration of Nuremberg-Principle Accountability

Restoring Nuremberg-principle accountability requires structural intervention across multiple institutional domains, each targeting the specific mechanism through which accountability eroded.

First, congressional assertion of appropriations authority to restrict enforcement. Congress could enact appropriations legislation explicitly prohibiting detention based upon administrative reclassification, profiling, or violations of due process.

Appropriations riders—attaching conditions to funds—have historically constrained executive action when other mechanisms failed. Such legislation, with explicit prohibition on funds for specified enforcement tactics, would force executive choice: comply or cease enforcement.

While Republican-controlled Congress faces internal resistance to such constraints, minority party advocacy and procedural mechanisms (discharge petitions, minority amendments) permit constraint attempt.

Second, state and local resistance through sanctuary policies and facility prohibition. States and municipalities could enact laws prohibiting state/local law enforcement cooperation with federal immigration enforcement and prohibiting state/local facilities from detaining federal immigration detainees. Such "sanctuary" policies—already enacted by numerous jurisdictions—leverage federalism to constrain federal authority.

Expansion of such policies would restrict federal enforcement capacity, particularly reliance on state/local cooperation through 287(g) agreements and facility access.

Third, judicial recalibration through rigorous Administrative Procedure Act review and standing doctrine. District courts could resist appellate pressure by demonstrating that government arguments lack evidentiary support (as was true in Noem—ICE submitted no evidence stops were based on factors other than the 4 profiling criteria).

Judges could invoke standing doctrine to reach merits of claims (as several district judges have begun attempting). Some lower courts have refused to apply Noem broadly, constraining its precedential scope. While appellate reversal remains likely, such resistance creates record and slows normalization.

Fourth, international accountability mechanisms. The International Criminal Court's Office of the Prosecutor could open preliminary examination into whether systematic detention and racial profiling constitute potential crimes against humanity.

While ICC jurisdiction over U.S. citizens appears limited absent Assembly of States Parties action, opening preliminary examination would establish international evidentiary record and create reputational pressure.

Prior instances (Palestine, Philippines, Myanmar) demonstrate ICC preliminary examinations' capacity to constrain state behavior through international scrutiny and potential future accountability.

Fifth, civil society documentation and counter-narrative. Organizations including American Civil Liberties Union, Immigrant Defenders Law Center, and investigative journalists have documented detention conditions, profiling patterns, and violence through photographs, testimony, and data analysis.

Such documentation creates evidentiary record for potential future accountability whilst delegitimizing official narratives. Counter-narrative campaigns humanizing detained immigrants undermine dehumanizing administrative classifications.

Conclusion

The Institutional Moment and Democratic Resilience

Kelley warned that democracy's vulnerability lay not in explicit coups or violent seizures but in gradual institutional erosion through which "ambitious climbers" positioned in governmental apparatus could systematically dismantle constraints through procedural mechanisms. Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo represents precisely this mechanism: no explicit constitutional amendment, no dramatic judicial coup, but rather incremental deference to executive authority combined with subordination of lower courts and obstruction of legislative oversight.

The comparison to Nuremberg proves instructive not because ICE constitutes equivalent to Holocaust apparatus (a historically inaccurate and ethically fraught comparison) but rather because both exemplify the mechanism through which bureaucratic systems enable ordinary people to perpetrate systematic injustice.

Nuremberg defendants claimed to merely follow orders; contemporary ICE officers similarly perform their functions within institutional parameters. Nuremberg decision-makers argued administrative necessity; contemporary judicial actors similarly defer to executive necessity. The institutional mechanism proves identical; only scale and explicit intent vary.

Whether democratic institutions possess sufficient resilience to arrest this erosion remains contested.

Kelley identified as necessary conditions for democratic resistance: widespread voter capacity to distinguish demagoguery from legitimate leadership; robust institutional independence and professional standards; and citizen commitment to constraining executive authority. Each condition appears attenuated in contemporary America.

Yet Nuremberg itself demonstrates that democratic institutions, though damaged, can constrain authoritarian consolidation when accountability mechanisms ultimately function.

The trials occurred only years after Nazi institutional capture; they required Allied military victory but demonstrated that eventual accountability remained possible.

The critical question is temporal: whether democratic institutions in the United States can reassert constraints before normalization completes itself. Procedural norms, once detention becomes a routine administrative function and judges routinely capitulate to executive authority, make institutional restoration exponentially more difficult.

Noem represents not endpoint but inflection point in this trajectory—the moment when the Supreme Court formally validated practices that would have triggered a constitutional crisis in prior decades.

What remains contested is whether this institutional moment stimulates democratic resistance or signals its conclusion.