Liberation and Supply Shock: Oil Markets at a Geopolitical Inflection Point

Executive Summary

The capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and escalating pressures on Iran’s regime represent watershed geopolitical events with profound implications for global oil markets. Yet the economic consequences will unfold across vastly different timescales than prevailing media narratives suggest.

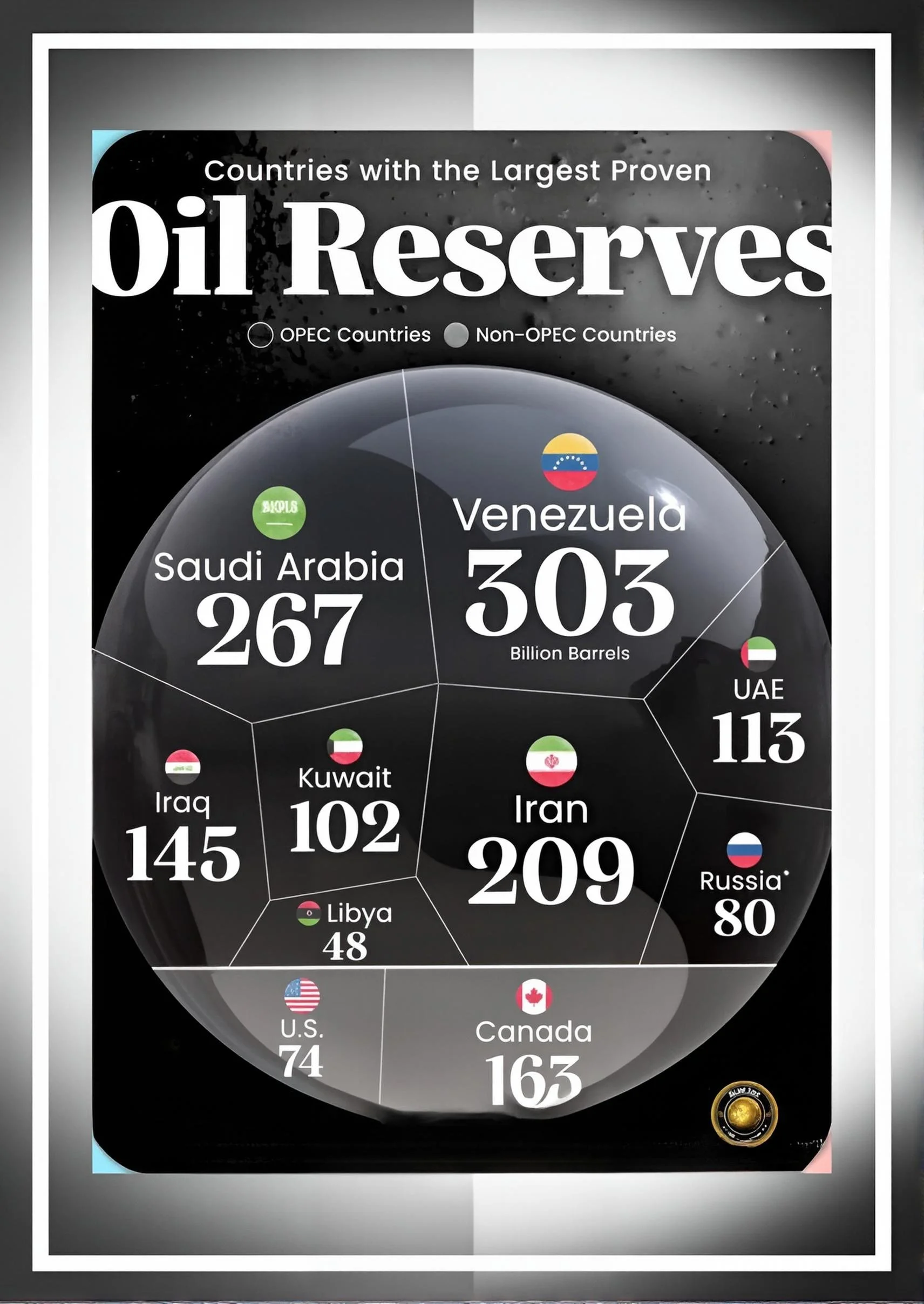

Venezuela’s oil production will not surge dramatically in the near term despite possessing the world’s largest proven reserves of 300 billion barrels; unlocking meaningful incremental supply requires a decade and over $100 billion in capital investment. Iran’s potential production increase of 400,000 to 500,000 barrels daily remains contingent on regime change or nuclear sanctions relief—scenarios with uncertain probability and timeline.

Simultaneously, the global oil market faces a structural oversupply condition projected to reach a record 3.84 million barrels per day deficit in 2026, driven by new production from the United States, Brazil, and OPEC producers across an environment of weakening demand growth.

Contrary to assumptions of dramatic price declines below $30 per barrel, the oil market is unlikely to experience catastrophic price collapse. A consensus of major financial institutions forecasts oil trading between $52 and $57 per barrel throughout 2026, with an effective floor around $55 supported by OPEC’s production management discipline and structural underinvestment in new reserves since 2020.

The recession probability stands at approximately 30 to 42 percent according to major forecasters, with most analysts expecting global GDP growth to remain modestly positive at 2.5 to 2.8 percent.

Under this baseline scenario, the global economy emerges stronger from lower energy costs despite the geopolitical turbulence, while oil-dependent economies face revenue pressures requiring strategic adaptation.

Introduction

The January 2026 military operations removing Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro from power—coupled with mounting U.S. sanctions pressure on Iran—have triggered a profound recalibration of global energy market expectations.

For decades, Western policymakers have viewed Venezuela’s 300 billion barrel oil reserves as an underutilized strategic asset, while Iran’s potential to restore production toward its historical capacity of 6 million barrels daily has haunted energy markets as a latent supply shock.

The immediate question consuming markets and policymakers is whether these events presage a radical transformation: will liberalized regimes unlock massive new oil supplies that crash prices toward $30 per barrel and trigger global recession, or will structural constraints preserve price stability and foster economic recovery through energy cost relief?

The answer requires disaggregating narrative from reality.

Both Venezuela and Iran face formidable obstacles to rapid production expansion that transcend regime politics. Venezuela’s oil infrastructure has deteriorated dramatically over two decades; its crude is among the world’s heaviest and most expensive to extract; and foreign capital has been driven from the nation by sanctions and political instability. Iran, while maintaining greater technical capacity and existing production infrastructure, remains constrained by decades of underinvestment, aging reservoirs requiring enhanced recovery techniques, and the physical reality that even sanctions relief cannot instantaneously mobilize idle capacity.

Meanwhile, the global oil market is experiencing simultaneous supply growth from non-OPEC producers, particularly U.S. shale, creating a demand environment where incremental barrels from Venezuela or Iran will face substantial headwinds rather than price spikes.

This analysis examines the technical and economic realities underlying these geopolitical shifts, assesses the actual timeline for meaningful supply additions, evaluates competing scenarios for the global economy, and identifies the asymmetric risks that could either amplify or constrain the impact of these pivotal events.

Venezuela: Liberation Without Immediate Gratification

Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves, estimated at over 303 billion barrels—roughly 17 percent of global supply—yet this theoretical abundance masks a production reality of profound decline. The nation currently produces approximately 900,000 to 1.14 million barrels daily, down from 3 million barrels at the peak of Hugo Chávez’s oil nationalist policies and nearly 3.5 million in 1999 before the Socialist regime’s rise. This thirty-year collapse reflects not reserve depletion but the systematic destruction of productive capacity through nationalization, underinvestment, corruption, and international sanctions.

Chevron, the sole major U.S. oil operator permitted under Trump administration exemptions, currently produces only 150,000 to 160,000 barrels daily—approximately 17 percent of Venezuela’s total output.

The company operates under a specialized license structure in which it may sustain existing joint ventures but cannot initiate new projects or substantially expand production; its operations simultaneously generate repayment of hundreds of millions of dollars in accumulated debts owed by PDVSA, Venezuela’s state oil company. This arrangement represents leverage rather than liberation: it allows the U.S. government to calibrate Venezuela’s energy sector while constraining rapid capacity expansion.

The fantasy of Venezuelan production surging toward 4 to 5 million barrels daily encounters three implacable technical constraints.

First, Venezuela’s crude is “extra-heavy” and “sour”—terms indicating both extreme viscosity requiring specialized processing and elevated sulfur content that complicates refining. These characteristics necessitate not merely capital but a specific category of technical expertise that international oil majors possess but which has largely evacuated Venezuela during decades of political instability.

Second, the nation’s energy infrastructure—pipelines, storage facilities, export terminals—consists substantially of equipment exceeding fifty years in age, corroded by tropical climates, deferred maintenance, and inadequate investment.

Third, and most critically, PDVSA and the Venezuelan state lack the financial resources to fund restoration internally; the state oil company functions as a revenue source for whatever government emerges from the post-Maduro transition rather than as a profit center capable of self-financed expansion.

Francisco Monaldi, director of the Latin America energy program at Rice University and among the most authoritative analysts of Venezuelan petroleum, estimates that restoring production to 1990s levels would require a minimum of $8 billion, while achieving the optimistic scenario of 4 to 5 million barrels daily would necessitate over $100 billion in capital investment across a timeline of at least a decade.

This is not a technical problem amenable to rapid solution through regime change; it is a capital accumulation problem. Even an ideally cooperative post-Maduro government cannot conjure the foreign investment, technology transfer, and managerial expertise from external sources faster than the physical process of infrastructure reconstruction permits.

The Trump administration has announced ambitions for major U.S. company participation in Venezuelan energy sector rehabilitation. Yet the licensing structure likely to emerge will necessarily balance three competing objectives: restoring production to generate government revenue that legitimizes the post-Maduro regime, permitting U.S. companies adequate profit opportunity to justify billions in capital commitment, and maintaining U.S. geopolitical leverage through controlled energy access. This balance points toward gradual, not explosive, production expansion.

Monaldi’s estimates suggest that even under optimistic political and financial scenarios, Venezuelan production could realistically increase by several hundred thousand barrels daily within a five-to-ten-year window. The notion of Venezuela adding multiple million barrels weekly to global markets rests on fantasy rather than physics.

Iran: Dormant Capacity and Regime Fragility

Iran occupies a paradoxical position in global energy markets: it possesses the fourth-largest proven oil reserves at approximately 157 billion barrels and controls 18 percent of global natural gas reserves, yet it produces only 3.3 million barrels daily—substantially below its technical capacity of 4 million-plus and a fraction of the 6 million barrels daily achieved in 1974 prior to the Islamic Revolution.

This gap reflects not geological limitation but the cumulative impact of three consecutive regimes—revolutionary instability, the Iran-Iraq War, and thirty years of international sanctions—that have collectively starved the petroleum sector of the $200 to $500 billion in investment necessary for infrastructure modernization and production expansion.

Iran’s current export achievement merits particular attention. Despite comprehensive U.S. sanctions reimposed in 2018 following the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and notwithstanding UN sanctions snapback that occurred in September 2025, Iran has managed to maintain crude oil exports of 1.5 to 1.7 million barrels daily—a feat enabled primarily through Chinese demand and the sophistication of Iran’s shadow fleet of vessels designed to evade maritime tracking.

This resilience indicates that Iran possesses both latent technical capability and external market access more robust than sanctions architects anticipated.

However, the speculative scenario of rapid Iranian production expansion remains constrained by three factors. First, Iran’s technical capacity to increase output by 500,000 barrels daily within six months of sanctions relief—an estimate from energy analysts—represents theoretical potential rather than near-term reality.

Enhanced oil recovery techniques required to combat natural field decline demand coordinated international technology transfer and capital investment. Second, and more politically salient, no imminent evidence suggests that the Iranian regime faces existential collapse. While regional tensions between Israel and Iran have spiked dramatically, the Islamic Republic’s state apparatus remains organizationally intact and capable of repression.

Analysts at JPMorgan examined eight historical instances of major oil-producer regime change since 1979, finding an average oil price spike of 76 percent at peak disruption, before stabilizing approximately 30 percent higher than pre-crisis levels. Yet Iran’s regime change remains speculative rather than baseline expectation.

Third, a nuclear sanctions relief scenario—potentially achievable through diplomatic settlement and more plausible in the medium term than regime change—presents its own ambiguities. While removing U.S. and international sanctions would eliminate barriers to capital inflow and technology access, it would not instantaneously mobilize dormant production capacity.

Fields subjected to decades of underinvestment require careful assessment and gradual capacity restoration; accelerating extraction risks permanent damage to reservoir geology. Market analysis suggests that a nuclear deal permitting gradual Iranian production expansion could add approximately 400,000 barrels daily to global supply, but such expansion would unfold across years rather than months.

The Global Oil Market: Oversupply as the Defining Condition

Against this backdrop of constrained Venezuelan potential and uncertain Iranian trajectories, the defining characteristic of the 2026 oil market is not supply scarcity but supply abundance.

The International Energy Agency projects a record global oil oversupply of 3.84 million barrels daily in 2026—a condition emerging not from Venezuelan liberation or Iranian production but from the combination of sustained U.S. shale growth, robust non-OPEC production in Brazil and other regions, and ongoing OPEC+ supply additions despite organizational discipline. Global demand is projected to grow only 860,000 barrels daily in 2026, creating a demand-supply mismatch of extraordinary proportions.

The consensus forecast from major financial institutions converges around oil prices in the $52 to $57 per barrel range throughout 2026. The EIA projects Brent crude averaging $55 per barrel in the first quarter and remaining near that level; JPMorgan forecasts $53 annually; Goldman Sachs anticipates $52; Bank of America projects $57.

This tightness around consensus reflects not analytical certainty but rather the recognition that while downside risks exist—principally from recession, peace in Ukraine, or further geopolitical surprises—structural factors likely prevent catastrophic price decline below $50 per barrel.

These structural factors merit examination. Following the dramatic 2020 price collapse to below $40 per barrel, capital discipline in the oil industry has constrained new project development. Discovery rates remain low; long-term projects have been postponed; the natural decline of existing fields continues to reduce baseline production.

OPEC+ has demonstrated consistent commitment to output management, preferring to accept market share loss rather than permit wholesale price collapse. This policy stance effectively creates a price floor around $55 to $60, below which further supply reductions become economically and politically necessary. Simultaneously, demand destruction has proceeded more slowly than peak bearishness anticipated; aviation, petrochemicals, and emerging market consumption retain resilience. The combination of fragile but non-collapsing demand and managed supply suggests the global oil market is likely to avoid both the $30-per-barrel crash of bearish scenarios and any substantial price recovery above $70 to $75.

Recession risk and Macroeconomics implications

The probability of a global recession in 2026 remains a material but not dominant outcome. Moody’s Analytics assesses the recession probability at approximately 42 percent—markedly elevated above the historical norm of 15 percent for healthy economies—while Bloomberg consensus forecasts place the probability at 30 percent.

These numbers reflect the extraordinary policy uncertainties of the current environment: elevated tariffs, immigration restrictions potentially constraining labor force growth, monetary policy operating with a lag, and geopolitical tensions that could disrupt trade flows or investment confidence. Most baseline economic forecasts, however, project global GDP growth to remain modestly positive in the 2.5 to 2.8 percent range, with U.S. growth accelerating to 2.6 percent and China achieving 4.8 percent despite domestic property sector weakness.

The relationship between oil prices and recession risk presents an asymmetry favorable to global economic resilience. If oil prices remain in the $55 to $60 range, energy cost relief provides stimulus to consumer purchasing power and corporate profitability across developed economies heavily dependent on energy imports.

This effect should partially offset deflationary pressures from tariffs and support continued consumption. Conversely, if geopolitical disruption—whether from escalated Iran-Israel conflict, renewed Russian-Ukrainian violence, or Venezuelan instability—precipitates an unexpected supply shock driving prices above $75, inflation re-acceleration could force central banks to maintain or raise policy rates, constraining growth more severely. The current consensus thus reflects an expectation of moderately positive growth enabled partially by low oil prices, contingent on avoidance of major geopolitical surprises.

A secondary but material risk concerns the health of energy-producing economies dependent on oil revenue. Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and numerous smaller producers have constructed fiscal frameworks around assumption of higher average oil prices.

Brent crude sustaining $55 per barrel represents a meaningful revenue haircut for these regimes compared to their fiscal break-even points. This dynamic creates political incentives toward OPEC+ supply discipline—an outcome already observable in organizational announcements of paused production increases—while simultaneously generating political pressure toward conflict as alternative means of disrupting competitor supply and supporting prices.

The U.S. military action against Venezuela itself likely reflects calculation that lower oil prices harm both Venezuelan fiscal capacity and broader anti-American geopolitical coalitions (particularly China and Russia) while simultaneously creating opportunities for U.S. corporate participation in energy sector reconstruction.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis: Geopolitics, Supply, and Markets

The causal chain linking Venezuela’s regime change to oil market consequences requires careful specification. The removal of Maduro does not directly add barrels to global supply; it instead removes political constraints that had prevented foreign capital and technology from rehabilitating Venezuelan petroleum infrastructure. The effect is permissive rather than immediate.

Over a five-to-ten-year window, the availability of U.S. capital, Chevron’s technical expertise, and potentially other major oil companies’ participation could restore Venezuelan production incrementally toward 2 to 3 million barrels daily. This would represent genuine, meaningful supply expansion—potentially adding 1 million-plus barrels to global balances—but on a timeline aligned with infrastructure reconstruction rather than geopolitical surprise.

Similarly, Iran’s trajectory depends on cascading political contingencies. In the scenario of limited sanctions relief through negotiated nuclear settlement, Iranian production might gradually increase toward 4 million barrels daily, adding approximately 400,000 to 500,000 barrels daily beyond current levels but across a horizon of several years. In the scenario of rapid regime change—substantially less probable based on current intelligence assessments—Iran might temporarily disrupt global supply through Strait of Hormuz blockade, potentially driving prices above $100 per barrel despite broader oversupply conditions. But sustained production expansion in a post-regime-change scenario faces identical infrastructure and capital constraints that limit Venezuela.

The global economy’s response to these supply scenarios splits into two pathways.

The gradual-expansion pathway—involving Venezuelan and potential Iranian supply additions unfolding across multiple years into an environment of broader supply growth from non-OPEC sources—results in downward pressure on oil prices but not catastrophic decline, as OPEC’s supply management and structural underinvestment provide countervailing support. Lower energy costs would provide stimulus to energy-importing economies, supporting consumption and reducing inflation pressures, thereby lowering central bank policy rate pressure and reducing recession probability.

This pathway corresponds to the consensus baseline forecast: 2.5 to 2.8 percent global growth, modestly positive real income growth for energy-importing populations, and accelerated corporate profitability in sectors benefiting from lower input costs.

The disruption pathway—involving escalated Iran-Israel conflict, Strait of Hormuz blockade, or geopolitical miscalculation triggering supply shock above existing oversupply conditions—generates the opposite dynamic. Price spikes above $75 to $80 per barrel would reintroduce energy-driven inflation, force central banks toward tighter monetary policy, constrain consumption growth, and elevate recession probability toward or beyond the 40 percent range.

This scenario appears less probable based on current geopolitical intelligence, but its potential impact justifies the elevated baseline recession probability that major forecasters have incorporated into their analyses.

Latest developments and market status

As of January 2026, Brent crude is trading around $60.75 per barrel, down 20.6 percent year-over-year, having registered its worst annual performance since 2020. West Texas Intermediate crude trades at approximately $57.32 per barrel. These price levels already reflect market expectations of continued oversupply, with the consensus that additional supply from Venezuela and Iran—to the extent it materializes—will face headwinds rather than generate dramatic demand response. OPEC+ is scheduled to meet on January 4, 2026, with expectations that the organization will maintain a pause on further production increases through the first quarter, a posture consistent with managing a fragile price floor.

The Trump administration has signaled aggressive intentions toward Venezuela’s energy sector rehabilitation, with statements that U.S. oil companies will “invest billions” in infrastructure restoration. However, actual capital deployment will necessarily proceed through standard corporate capital allocation processes, with returns-based decision-making and risk assessment governing investment sequencing.

Chevron has indicated cautious optimism while emphasizing compliance with sanctions frameworks, a formulation suggesting neither dramatic acceleration nor deliberate obstruction of production expansion.

Regarding Iran, the situation remains more fluid. The UN sanctions snapback of September 2025 has not substantially reduced Iranian oil exports because the measure did not explicitly target the energy sector, and because China has continued to purchase Iranian oil at steep discounts through shadow fleet mechanisms. However, the Trump administration’s explicit commitment to “maximum pressure” on Iran suggests that additional U.S. sanctions beyond snapback are forthcoming.

The question of regime change remains speculative, with no current evidence of imminent state collapse, though ongoing Israel-Iran tensions create genuine risk of escalation.

Future pathways and scenarios

Three distinct scenarios merit development, ordered by probability.

The baseline scenario—deemed most probable by major forecasters and bond markets—involves modestly positive global growth of 2.5 to 2.8 percent, with oil trading in the $52 to $57 range throughout 2026. Venezuelan production increases gradually from 900,000 to perhaps 1.2 to 1.4 million barrels daily by decade’s end, with Chevron and potentially ConocoPhillips expanding operations incrementally. Iran’s production remains in the 3.3 million barrel range absent regime change or major sanctions relief. Global supply oversupply persists throughout the year, with OPEC+ maintaining output discipline to prevent price collapse.

Lower oil prices support consumer consumption and corporate profitability, offsetting some deflationary pressure from tariffs. Central banks maintain or modestly reduce policy rates. No major recession occurs, though growth rates remain below the post-pandemic averages of 2019.

A secondary scenario—moderately probable at approximately 30 to 35 percent—involves a mild U.S. recession driven by combination of tariff drag, lagged monetary policy effects, and confidence disruption. In this scenario, global oil demand weakens, OPEC is forced toward sharper production cuts to maintain prices above $50 per barrel, and both developed and developing economies experience slower growth than the baseline forecast.

However, even in this scenario, an absence of major supply disruption limits oil price spikes; energy costs decline in real terms despite lower absolute price levels, and the recession remains mild with unemployment rising modestly.

This scenario corresponds to the more pessimistic forecasts from Deloitte and similar institutions projecting 1.4 to 2.0 percent growth. Even in this case, the catastrophic $30-per-barrel scenario does not materialize because demand reduction induces supply discipline.

A tertiary scenario—lower probability at approximately 15 to 20 percent but with disproportionate consequences—involves geopolitical escalation in the Middle East, whether through Iran-Israel conflict escalation, Strait of Hormuz blockade, or unanticipated regional conflict. In this scenario, oil prices spike toward $75 to $100 per barrel, energy inflation re-emerges globally, central banks tighten policy rates, and recession probability exceeds 50 percent.

This outcome would generate material economic damage across energy-importing economies, though the oversupply condition limits how elevated prices would rise compared to historical precedents. The probability of this scenario has risen somewhat due to the Israel-Iran regional tension, but it remains below the baseline scenario probability.

Will Oil Plummet Below $30 or Will the Global Economy Face Recession?

The binary framing of the original question presents a false dichotomy. Oil will not plummet below $30 per barrel in 2026 absent either a dramatic economic collapse (unlikely at 30 percent probability) or a geopolitical shock releasing enormous supply (inconsistent with timeline realities for both Venezuela and Iran). The global economy will not face significant recession probability above 40 to 50 percent unless geopolitical disruption materializes.

Instead, the most probable scenario involves oil trading between $55 and $65, global growth remaining modestly positive at 2.5 to 2.8 percent, and energy consumers experiencing cost relief that partially offsets other economic headwinds.

The Venezuelan situation illustrates this dynamic. While regime change removes political impediments to capital investment and technological restoration, it does not eliminate the decade-long timeline for meaningful infrastructure rehabilitation. Adding even 1 million barrels daily to global markets is a transformative achievement for Venezuela, but it represents only a modest fraction of global supply (approximately 0.9 percent) in an environment of ongoing growth from other regions.

Iran faces identical timeline constraints. Neither country can deliver the supply shock that would drive prices below $30 unless simultaneously coupled with demand collapse from major recession—a scenario less likely than the baseline of continued moderate growth.

The OPEC+ price floor mechanism merits particular emphasis. The organization has demonstrated consistent willingness to reduce production to maintain price discipline, and its core members—particularly Saudi Arabia—have sufficient financial capacity to sustain production cuts despite revenue pressure.

This mechanism likely prevents prices from falling below $50 to $55 unless a recession of sufficient severity (exceeding 40 percent probability threshold) emerges. Conversely, supply management prevents dramatic price spikes unless geopolitical disruption genuinely constrains supply. The oil market in 2026 is likely to reflect this range-bound, managed-supply dynamic rather than either extreme of the initial question.

Implications for OPEC, competing economies, and global stability

OPEC+ faces a challenging environment where production discipline must balance multiple objectives: maintaining prices sufficient to fund member economies’ fiscal needs, retaining market share against non-OPEC+ growth, managing internal cohesion as producer interests diverge, and responding to geopolitical pressures from the United States and other powers.

The organization’s decision to pause production increases through the first quarter of 2026 reflects acknowledgment that additional supply would depress prices below sustainable levels. However, this decision also acknowledges that demand growth remains too weak to absorb OPEC’s full available capacity.

Non-OPEC+ producers—particularly the United States, Brazil, and Canada—continue expanding production despite lower prices, as shale economics have improved and capital discipline has yielded efficiency gains. U.S. production is projected to grow by approximately 460,000 barrels daily in 2025 but only 100,000 in 2026 as growth naturally decelerates. Brazil continues developing pre-salt offshore assets at steady pace.

The cumulative effect of non-OPEC+ growth, even at moderating rates, means that global supply growth outpaces demand expansion in 2026, creating persistent downward price pressure that OPEC+ must countervail through output reduction.

For economies dependent on oil revenues—Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Venezuela—the $55 to $60 price environment represents material fiscal stress.

Most of these governments calibrated their budgets around assumptions of $70 to $85 per barrel. The mathematics are stark: if Saudi Arabia’s government requires $80 per barrel to balance its budget and oil trades at $58, the kingdom must either cut expenditures, borrow internationally, or deploy reserves. Similar pressures affect other major producers.

This dynamic creates perverse incentive structures toward conflict or supply disruption as alternative mechanisms for price support. Conversely, it creates incentive for cooperation on supply discipline among producers, a dynamic that OPEC+ has largely managed effectively.

For developed economies dependent on energy imports—the European Union, Japan, India—lower oil prices represent genuine economic stimulus. A barrel priced at $58 rather than $85 represents approximately 30 percent cost reduction for petroleum products, translating directly into lower transportation costs, reduced heating expenditures, and lower input costs for petrochemical-dependent industries.

This stimulus effect partially offsets deflationary pressures from trade barriers and supports consumption growth even if headline GDP growth moderates. The distributional consequences favor poorer consumers (for whom energy represents a larger budget share) and energy-intensive industries over upstream oil producers.

Conclusion

The capture of Venezuela’s Maduro and escalating pressures on Iran represent genuine geopolitical inflection points with consequential implications for global energy markets and economic stability. However, the actual economic consequences will unfold across timescales and magnitudes substantially different from both optimistic narratives of immediate Venezuelan production surge and pessimistic scenarios of $30-per-barrel price collapse and global recession.

Venezuela possesses the world’s largest oil reserves but remains constrained by decade-long infrastructure restoration requirements, hundreds of billions in capital needs, and technical expertise gaps that regime change alone cannot immediately overcome. Iran faces similar constraints despite greater existing production capacity and technical sophistication.

Simultaneously, the global oil market faces a structural oversupply environment wherein incremental supply from either nation will encounter substantial demand-side headwinds rather than market premiums supporting price spikes.

The consensus forecast from major financial institutions converges around oil trading between $52 and $57 per barrel throughout 2026, with global economic growth remaining modestly positive at 2.5 to 2.8 percent.

This outcome reflects recognition that while downside risks exist—principally from recession or geopolitical disruption—structural factors including OPEC+ supply discipline, moderate but persistent demand growth, and capital constraints on non-OPEC+ expansion likely prevent both catastrophic price collapse below $30 and demand destruction sufficient to trigger a significant recession.

For energy-importing economies, this scenario delivers genuine economic benefit through energy cost relief, supporting consumption.

For energy-exporting economies, it requires difficult fiscal adjustments and potentially generates political pressure toward conflict or cooperation on supply management.

The global economy emerges from these geopolitical events with lower energy costs but heightened geopolitical tension—a net positive outcome for aggregate welfare but with profoundly uneven distributional consequences across nations and economic sectors.