A House Divided: How Internal Power Struggles and External Interference Shape Iraq's Foreign Policy in 2026

Executive Summary

Iraq stands at a critical juncture in January 2026. The nation's internal fractures—driven by an entrenched sectarian system, competing militia factions, and weak state institutions—have made it vulnerable to unprecedented external interference.

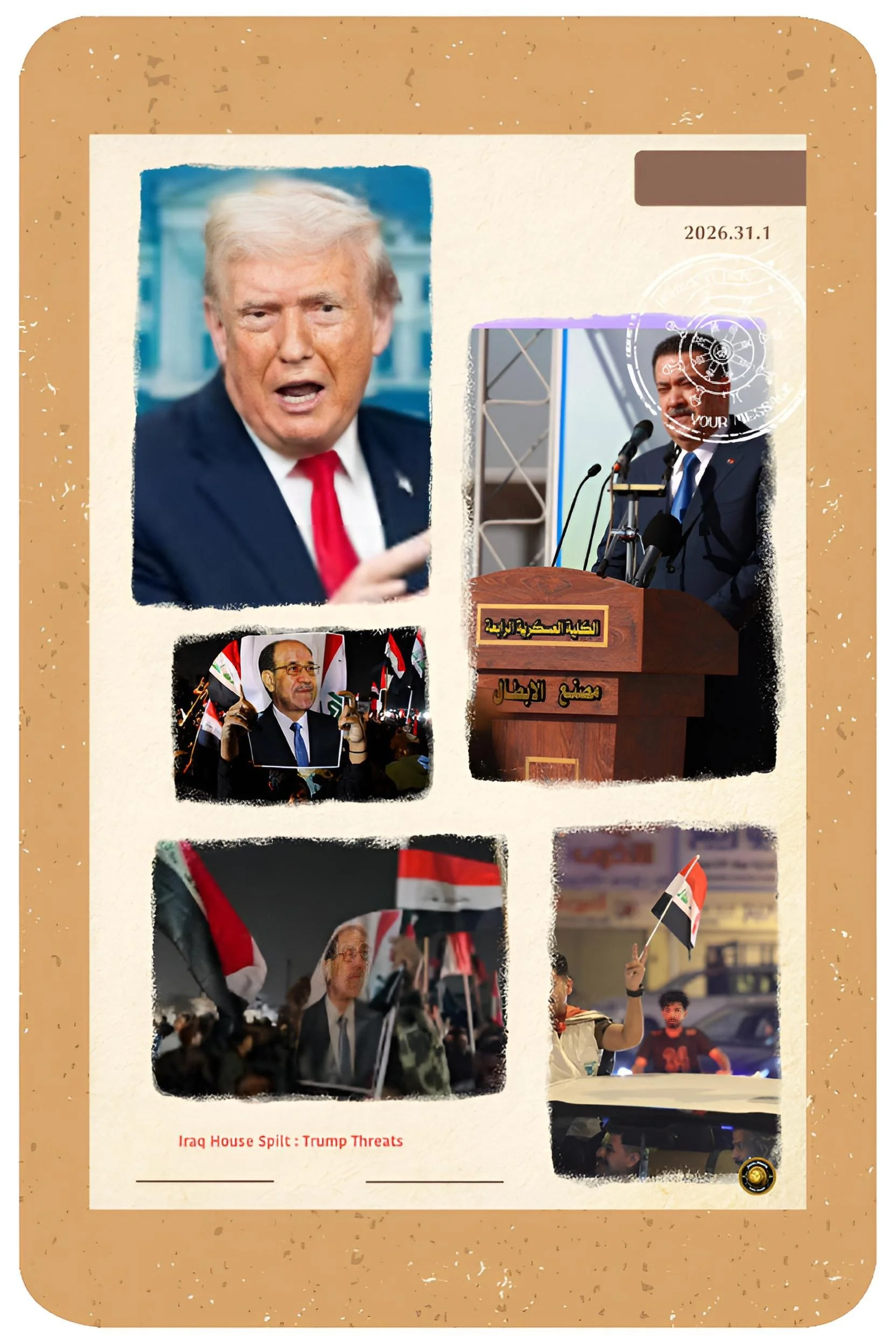

The Trump administration's direct intervention in Iraq's political process, including threats to withdraw all assistance if former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki returns to power, represents a dramatic escalation of American interference. Simultaneously, the United States has accelerated military withdrawal while the collapse of the Assad regime in Syria has created a security vacuum that threatens to destabilize Iraq through ISIS resurgence.

Iraq's attempted balancing act between Washington and Tehran has become increasingly untenable.

Geographic proximity to Iran, 40% dependence on Iranian energy supplies, and 67 Iranian-backed militia factions embedded within state institutions create structural constraints that limit Baghdad's strategic autonomy.

The convergence of domestic fragmentation, external pressure from both Washington and Tehran, and regional instability from Syria creates a complex nexus that Iraq's divided political leadership appears ill-equipped to manage.

Introduction

The Architecture of Division

Iraq's contemporary foreign policy predicament emerges not from external constraints alone but from the intersection of deep internal divisions and new external pressures.

Since 2003, Iraq has adopted a formal democratic architecture predicated on ethno-sectarian representation through a quota system known as "muhasasa." This institutional framework, rather than aggregating diverse interests into coherent policy, has instead calcified sectarian identities and empowered factional leaders to weaponize state resources for parochial advantage.

The Shia-dominated Coordination Framework—encompassing the Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) with 238,000 fighters and approximately $3.6 billion in annual budgetary allocation—has consolidated control over security institutions while maintaining organizational autonomy from formal state command structures.

Simultaneously, Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani represents a competing faction seeking to establish independent authority while navigating pressures from both Tehran and Washington. This fragmentation renders Iraq incapable of articulating coherent foreign policy positions or executing consistent strategic choices.

The Trump administration's public threats to withdraw support unless Maliki is excluded from government represents an extraordinary intervention into Iraq's ostensibly sovereign political process. These pressures arrive precisely as Syria's geopolitical transformation and American force reductions create security vacuums that incentivize regional actors—both Iranian and jihadist—to fill the resulting void.

Understanding Iraq's contemporary foreign policy requires comprehending how internal institutional breakdown has rendered the state susceptible to external manipulation.

Historical Context and Current Status

From State Collapse to Controlled Fragmentation

Iraq's institutional vulnerabilities trace to fundamental design choices made in the post-2003 transition.

Rather than constructing integrative state institutions based on citizenship and merit, Iraq's constitutional framework institutionalized sectarian representation through explicit quotas: Shiite majorities secured executive and judicial authority, Sunni Arabs received parliamentary representation through quota allocation, and Kurds gained regional autonomy. This sectarian federalism, adopted as a stabilization mechanism, produced precisely the opposite effect.

Militia formations organized along sectarian lines—particularly the PMF—became parallel state institutions answering to extraconstitutional authorities.

The Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) cultivated these relationships through long-standing patronage networks, offering military training, financial transfers, and intelligence support in exchange for institutional loyalty to Tehran's regional objectives.

This pattern intensified following the 2003 invasion: Iranian-backed militias consolidated control over portions of Iraq's internal security apparatus, while the PMF's formal incorporation into Iraq's security forces in 2014 provided institutional legitimacy to organizations that fundamentally operated under foreign command authority. By 2021, the structural dominance of Iran-aligned factions became undeniable.

The Coordination Framework—the umbrella organization of Shia parties and militias—institutionalized what analysts termed the "Shia House" principle: the requirement that all Shia political actors resolve their internal competition before negotiating with other ethno-sectarian groups.

This represented a reversion to sectarian majoritarianism after temporary aberrations toward inclusive governance.

The October 2021 elections produced a fractious outcome: Muqtada al-Sadr's Tripartite Alliance initially achieved numerical plurality, but the subsequent machinations by the Coordination Framework—including implicit threats of civil violence—forced Sadr's retreat and enabled the Framework's consolidation of power.

The emergence of al-Sudani as prime minister in October 2022 represented an attempt to escape this sectarian logic through technocratic governance. However, al-Sudani's authority has proven perpetually constrained by the Coordination Framework's superior organizational cohesion and the PMF's continuing institutional autonomy.

By January 2026, Iraq enters a period of unprecedented external pressure layered upon preexisting internal dysfunction.

Key Developments

Trump Administration Intervention and Regional Transformation

The Trump administration's intervention in Iraq's political process beginning January 26, 2026, represents an explicit departure from diplomatic convention.

Through social media statements and direct diplomatic communications from Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the administration announced that American support for Iraq would terminate entirely if the Coordination Framework's nominated candidate, Nouri al-Maliki, assumed the premiership.

Trump's explicit statement—"If elected, the United States of America will no longer help Iraq"—constituted direct interference in another nation's electoral process on grounds explicitly geopolitical: al-Maliki's characterized as "too close to Iran" and responsible for "poverty and total chaos" during his previous tenure from 2006 to 2014.

This intervention arrived as Iraq's security infrastructure has become increasingly dependent on external support precisely when American military presence is being withdrawn.

The December 2024 fall of the Assad regime in neighboring Syria created concurrent security pressures that undermined American negotiating positions.

As Syrian government forces advanced against the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—the primary American ally in countering ISIS—the strategic logic underlying American counterterrorism operations in Iraq became untenable.

The SDF's collapse by January 2026, forced to capitulate territorial control including the massive al-Hol detention camp housing tens of thousands of ISIS-affiliated individuals, created an immediate security vacuum.

Approximately 2,500 ISIS fighters remained active in Syria and Iraq, and intelligence assessments indicated that ISIS attacks across both countries would double during 2026. Critically, the Syrian government's assumption of control over ISIS detention facilities proceeded without demonstrated capacity to manage these facilities against escape risks.

The transition occurred precisely as the Trump administration accelerated its withdrawal of American forces from Iraq.

By January 19, 2026, the United States had completed evacuation from al-Asad Air Base in Iraq's Anbar Province, a facility that had hosted American forces for more than 2 decades.

The withdrawal left only approximately 250 to 350 American advisers at Harir Air Base in the Kurdish autonomous region, with complete American force exodus scheduled for September 2026.

This sequencing created a dangerous temporal dynamic: exactly as Syria's security collapse threatened to generate ISIS spillover into Iraq, American military capacity to respond to that threat was being systematically eliminated.

Prime Minister al-Sudani had originally committed to international force departure by September 2025 but postponed the deadline to September 2026 following Syria's transformation.

The implicit recognition was that Iraq's security forces, despite official claims of adequacy, remained dependent on American air support, intelligence coordination, and logistical infrastructure to contain ISIS threats.

Latest Facts and Strategic Concerns

The Mechanics of External Pressure and Internal Paralysis

The Trump administration's threats against Iraq operate through multiple mechanisms simultaneously.

First, direct political leverage: the explicit threat that American support—military, financial, and diplomatic—would terminate if particular political actors assumed power represents an unprecedented escalation of conditionality.

Former spokesman of Iraq's deputy prime minister, Entifadh Qanbar, publicly declared that "Iran personally blessed Nouri al-Maliki's nomination," confirming the Iran-aligned nature of the Coordination Framework's candidate.

Simultaneously, al-Sudani's breakaway candidacy split the Shia vote while maintaining his own dependence on the very sectarian factions he attempted to escape.

Second, economic leverage: Trump's administration imposed a 25% tariff on any nation conducting trade with Iran, directly threatening Iraq's $13 billion annual trade volume with Tehran and Iraq's critical dependence on Iranian gas and electricity for approximately 40% of national energy supply. Iraqi analysts acknowledge that Iraq cannot sever ties with Iran given geographic proximity and intertwined markets spanning centuries. This tariff threat creates direct economic costs for Iraqi policymakers regardless of their political orientation.

Third, financial infrastructure leverage: Iraq's oil export revenues, which constitute approximately 90% of government income, flow through banking systems controlled or monitored by American institutions, particularly the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

This infrastructure arrangement, established in 2003, provides Washington with ongoing financial leverage independent of political preferences.

Fourth, military vulnerability: the American troop withdrawal proceeds on a predetermined schedule regardless of conditions on the ground. Iraqi security forces, despite official claims of competence, lack the air power, intelligence, and coordination capabilities necessary to contain a resurgent ISIS.

The Brookings Institution assessed that without American support, Iraq "would be hard-pressed to manage" ISIS threats. These multiple pressure vectors converge upon an Iraqi political system already fractured by sectarian institutional design.

The PMF's continued expansion—growing from counter-ISIS forces to 238,000 fighters with $3.6 billion budgetary allocation despite ISIS territorial defeat occurring 8 years prior—indicates that Iranian-aligned factions view the security environment as permitting consolidation of military assets for future political and regional objectives.

The February 2025 visit by PMF Chairman Falih al-Fayyadh to senior Iranian officials demonstrated the organizational priority: maintaining Iranian patronage networks against proposed legislation that would implement mandatory retirement ages for senior commanders with long-standing ties to Tehran.

The proposed PMF legislation, advanced in July 2025, sought to institutionalize the militias further within Iraqi state structures—effectively cementing Iran's organizational presence within Iraq's formal security apparatus.

Evidence surfaced in January 2026 that nearly 5,000 Iraqi Shia militants had crossed into Iran to assist the Islamic Republic's suppression of anti-government protests, demonstrating the operational deployment of Iraq's paramilitary forces as instruments of Iranian state policy.

This pattern reveals a profound inversion: rather than Iraqi militias operating under state authority, state institutions have become operational extensions of extrastate militia networks whose ultimate command authority resides in Tehran.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis

Institutional Breakdown and Strategic Dependency

The fundamental cause of Iraq's contemporary foreign policy paralysis emanates from the muhasasa system's structural inability to produce coherent state authority.

By explicitly institutionalizing sectarian representation rather than citizen-based governance, Iraq's constitution created competing power centers authorized to extract state resources for factional purposes.

The PMF's incorporation into Iraq's formal security forces in 2014 appeared necessary to combat ISIS's military advancement but established a precedent: paramilitary organizations could secure state legitimacy while maintaining operational autonomy from constitutional authority structures.

By 2022, this structural precedent had become institutionalized. When the Coordination Framework faced electoral defeat to the Tripartite Alliance in October 2021, it deployed credible threats of civil violence to reverse the outcome.

Muqtada al-Sadr's subsequent withdrawal of his parliamentary delegation created a supermajority for the Framework, permitting both the elevation of al-Sudani and the Framework's preservation of agenda-setting power over national security issues.

Al-Sudani's subsequent appointment as Prime Minister represented a compromise: he possessed technocratic credibility useful for managing Iraq's economic stabilization while remaining institutionally constrained by the superior organizational power of the Coordination Framework.

This structural asymmetry produced precisely the predicament observable in January 2026: al-Sudani possesses formal executive authority yet lacks sufficient independent power to execute policies contrary to the Framework's interests.

The consequence: Iraq cannot adopt genuinely independent foreign policy positions when doing so requires confronting organizations that control security forces, command loyalty from paramilitary brigades, and maintain direct command relationships with extrastate authorities in Tehran.

When Trump issued threats regarding al-Maliki's potential return, no Iraqi leader possessed sufficient institutional autonomy to reject American demands based on national interest calculations alone.

Al-Sudani's own political survival depends on avoiding Framework retaliation, al-Maliki controls Framework machinery and maintains Iranian backing, and alternative political forces (including Sadr's boycotting Tripartite Alliance) lack institutional coherence.

The cascade effect: Iraq cannot credibly commit to policies independent of American demands because Iraqi leadership lacks institutional authority to execute such commitments. Simultaneously, Iraq cannot credibly align with American pressure against Iran because the very organizations upon which Iraq's state security depends maintain command relationships with Tehran.

This structural dynamic creates perverse incentives. Iranian-backed factions may welcome American withdrawal because it eliminates the contradictions inherent to balancing Washington against Tehran.

American military presence created institutional friction between American-backed state security forces and Iranian-backed militias. Withdrawal permits the unchallenged consolidation of Iranian influence without requiring overt contestation.

American policymakers appear to have calculated that threatening withdrawal of support unless particular politicians are excluded provides leverage over Iraqi decisions.

In reality, this approach may simply accelerate the very Iranian consolidation it aims to prevent. Iraqi actors viewing American commitment as conditional and temporary have incentives to accommodate Tehran's demands preemptively, recognizing that American military presence will terminate in September 2026 regardless of political outcomes.

Future Steps

Toward Institutional Rebuilding or Sectarian Ossification

Three potential trajectories present themselves for Iraq's political-institutional evolution over the next 12 to 36 months.

The first trajectory involves the return of Nouri al-Maliki as Prime Minister. This outcome would intensify sectarian governance patterns, deepen Iranian institutional penetration, and likely precipitate either American disengagement (as threatened) or American sanctions against Iraqi entities suspected of facilitating Iranian sanctions evasion.

The precedent of sanctions implementation already exists: the Trump administration has targeted Iraqi entities accused of assisting Iran's circumvention of American sanctions. Additional sanctions would constrain Iraq's already-limited economic flexibility.

The Brookings Institution assessed that Iraq's economic growth trajectory faces "imminent deceleration" and cannot withstand sustained American punitive measures.

Second, the al-Sudani faction could consolidate independent authority by breaking institutionally from the Coordination Framework.

This would require either securing electoral validation through new elections or constructing alternative parliamentary coalitions. Both require political capital that al-Sudani appears not to possess.

The Framework's superior organization, militia resources, and Iranian backing render it capable of blocking al-Sudani's independent consolidation.

Third, a compromise candidate could emerge from Framework negotiations, satisfying neither American nor Iranian preferences while preserving institutional fragmentation. This represents the most probable outcome given existing constraints. Beyond immediate political outcomes, Iraq faces systemic institutional challenges requiring longer-term reform.

The muhasasa system itself must be reformed to reduce the sectarian determinism of political outcomes. Merit-based recruitment for security forces would reduce Iranian-backed militia dominance, but implementing such reforms requires leaders willing to challenge organizations controlling military assets.

The integration of PMF forces into regular security institutions on subordinate terms—rather than coequal status—represents a critical requirement but faces organized opposition from militia commanders. The disarmament or integration of rogue militia factions designated as terrorist organizations by the United States presents another necessary but politically difficult reform.

Organizations like Kataib Hezbollah and Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba have resisted incorporation into state hierarchies and refused disarmament, insisting that only complete Iraqi sovereignty (including foreign troop departure) justifies relinquishing autonomous military capability.

Paradoxically, the American military withdrawal they demand is the precise condition that would eliminate the external pressure necessary to compel their integration into subordinate security roles. Baghdad's articulation of a "good neighbor" foreign policy represents the appropriate ambition: maintaining engagement with both Washington and Tehran while not becoming subordinated to either.

Achieving this balance requires state institutional coherence that Iraq currently lacks. Until Iraq's state apparatus demonstrates genuine authority over security forces and militia organizations, Iraqi foreign policy will remain constrained by factional competition rather than reflecting genuine national interest calculations.

The economic diversification away from oil dependence requires institutional capacity to implement long-term sectoral development strategies—precisely the capacity that sectarian institutional design undermines.

Conclusion

The Limits of External Intervention and the Imperatives of Institutional Reconstruction

Iraq's contemporary foreign policy crisis cannot be resolved through American threats or Iranian inducements because the fundamental problem is Iraq's inability to articulate coherent national preferences in the first place.

The Trump administration's direct intervention in Iraqi elections through threats of sanctions and withdrawal of support may temporarily constrain particular politicians' ascendance, but it cannot address the underlying institutional fragmentation that renders Baghdad perpetually vulnerable to external manipulation.

The collapse of the Assad regime in Syria has created security vacuums that threaten immediate spillover effects through ISIS resurgence. The security vacuum may intensify during the precise window in which American military capacity to respond is being systematically withdrawn.

These concurrent pressures make the next 9 months (until September 2026) critical for establishing new operational frameworks between Baghdad and Washington for sustaining counter-ISIS operations after American force departure.

The Iranian-backed militia question represents perhaps the most intractable challenge. These organizations have evolved from counterterrorism auxiliaries into permanent state institutions with independent command authority and external patronage.

Any genuine institutional reform requires either their integration into state hierarchies on clearly subordinate terms or their disarmament—both requiring levels of state authority that fractious Iraqi leadership currently lacks.

The Trump administration's threatened intervention may paradoxically strengthen Iranian influence by demonstrating to Iraqi actors that American commitment is conditional and temporary.

Stakeholders believing withdrawal to be certain have incentives to preemptively accommodate Tehran's demands, expecting Iranian commitment to remain constant.

Long-term Iraqi stability depends not on American threats or Iranian inducements but on domestic institutional reconstruction that Iraq itself must ultimately undertake.

The minimal prerequisite is creation of security force command structures in which military units answer to civilian constitutional authority rather than sectarian factions or foreign powers.

This requires political leadership to address preexisting challenges, as organizations commanding a military asset—a preexisting Iraq's currently fragmented political class—appear unable to satisfy.

Iraq will continue balancing between Washington and Tehran, but that balance will remain unstable and conditional until Iraq develops state institutions capable of executing an independent foreign policy. policy choices based on genuine national interest calculations rather than factional survival imperatives or external pressure cycles.