Stalin's Paranoia and Power: The Great Purge as a Catalyst for Soviet Institutional Collapse and Modern Geopolitical Lessons

Executive Summary

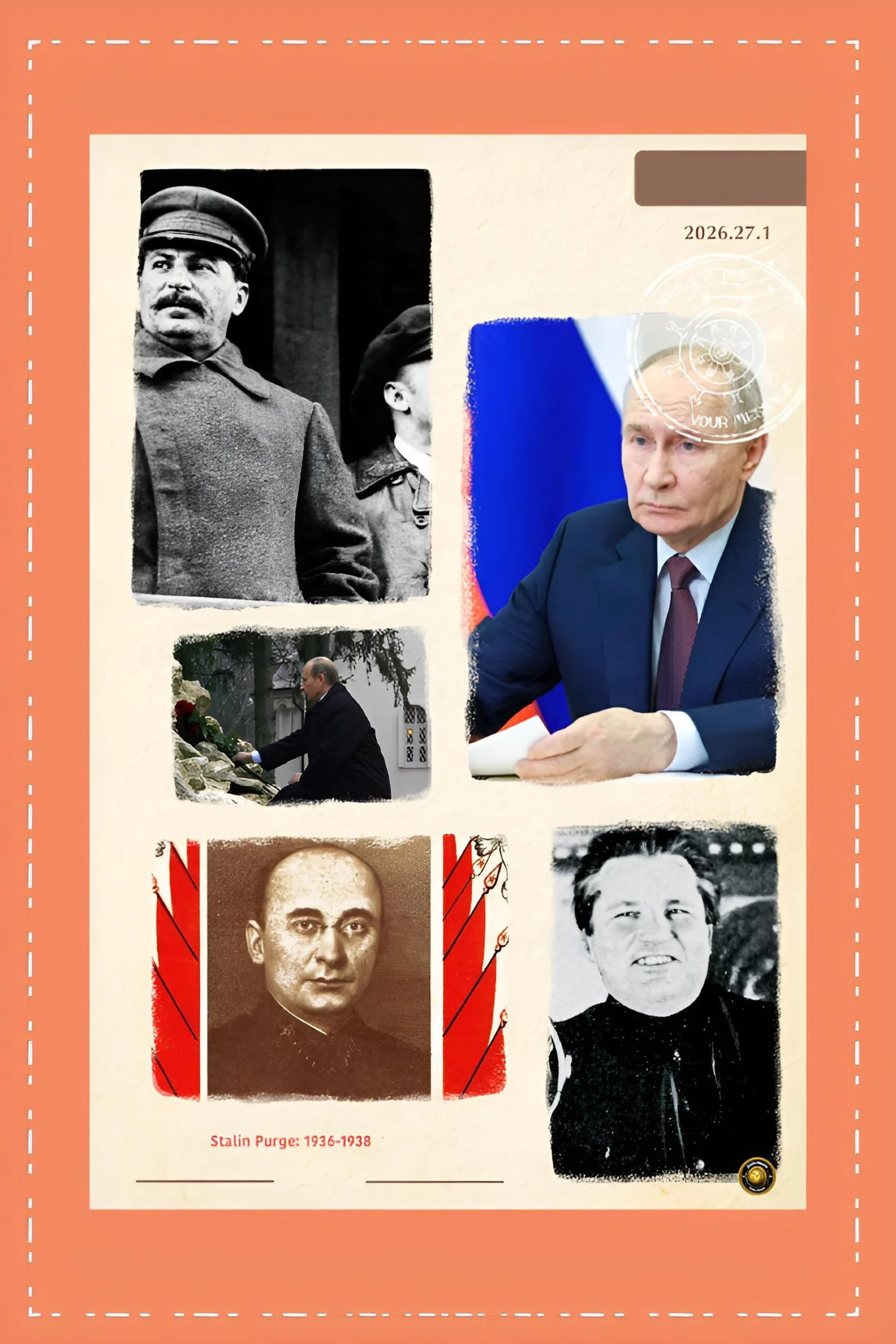

The Great Terror, spanning from 1936 to 1938 in the Soviet Union, represented one of the most devastating episodes of state-orchestrated violence in modern history.

Initiated following the assassination of party leader Sergei Kirov in December 1934, Stalin's purges systematically eliminated hundreds of thousands of perceived political opponents, military officers, party functionaries, and ordinary citizens.

Estimates place the death toll between 700,000 and 1.2 million individuals, with millions more subjected to imprisonment in the Gulag system.

Beyond the human tragedy, the purges fundamentally undermined Soviet institutional capacity, decimating the military leadership at precisely the moment when Germany posed an existential threat.

This historical episode illuminates critical geopolitical lessons applicable to contemporary authoritarian governance: the paradox that intensive internal purging signals underlying regime weakness rather than strength, the catastrophic consequences of eliminating institutional expertise in pursuit of absolute power consolidation, and the inevitability that fear-based governance structures collapse both legitimacy and operational effectiveness.

Modern authoritarian regimes, particularly in China and Russia, continue to employ purges as mechanisms of elite control, yet lack the ideological coherence of Stalinist totalitarianism, rendering them structurally more fragile and prone to catastrophic miscalculation under pressure.

Introduction

The Historical Context of Stalin's Rise

Joseph Stalin's consolidation of power following Lenin's death in 1924 represented a fundamental departure from collective Bolshevik leadership toward personalistic dictatorship. Having defeated his primary rival Leon Trotsky and systematically isolated other potential challengers by the late 1920s, Stalin established himself as the supreme leader through control of party apparatus and orchestration of ideological shifts favoring "socialism in one country" over Trotsky's doctrine of permanent revolution.

Yet this consolidation, achieved through political maneuvering and force, remained incomplete as Stalin entered the 1930s. His industrialization strategy through forced agricultural collectivization produced famine conditions in Ukraine and across the Soviet Union from 1930 to 1933, generating internal party dissatisfaction and questioning of his leadership from veteran Bolsheviks who had survived the Civil War and early Soviet period. These old revolutionaries, possessing both revolutionary credentials and potential alternative leadership claims, represented precisely the type of threat that Stalin's paranoid temperament found intolerable.

The purges that would commence in the mid-1930s emerged not from a position of absolute security but from underlying anxiety about the fragility of Stalin's personalistic authority system and the persistence of alternative power centers within the Communist Party apparatus.

The Catalyst and the System: From Kirov's Assassination to the Great Terror

On December 1, 1934, Sergei Kirov, the popular party leader in Leningrad and a high-ranking Politburo member, was assassinated by Leonid Nikolayev, a party member. While Nikolayev's personal grievances—possibly rooted in professional resentment and jealousy regarding Kirov's relationship with his wife—provided a plausible motivation, Stalin immediately seized upon this incident as justification for a comprehensive purge of alleged conspirators.

Historians remain divided on whether Stalin himself orchestrated Kirov's murder, though archival evidence demonstrates considerable tension between the two leaders and suspicions surrounding NKVD involvement. Regardless of the assassination's true origins, Stalin weaponized the event as a pretext for eliminating adversaries and consolidating absolute power.

The Kirov decree of December 1934 granted the NKVD (secret police) expanded authority to arrest, investigate, and execute alleged conspirators with minimal procedural restraint.

The initial targeting focused on former supporters of Trotsky and Zinoviev, particularly members of various opposition tendencies who had challenged Stalin's leadership during the 1920s. However, the subsequent escalation transformed the purges from a targeted elimination of identified rivals into a systemic campaign of mass terror.

Between 1936 and 1938, three major Moscow show trials publicized the alleged crimes of party luminaries including Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, and Nikolai Bukharin.

These trials featured confessions—many extracted through torture, threats against family members, and psychological manipulation—to fantastical conspiracies involving collaboration with Nazi Germany, Polish intelligence services, and exiled Trotskyists.

Defendants confessed to planning assassinations, sabotage, and the dismemberment of the Soviet Union, yet material evidence remained conspicuously absent.

The trials served a crucial propaganda function, providing apparent legal legitimacy to the broader violence and creating an atmosphere where denunciation became mandatory for self-preservation.

Party members understood that failure to report suspected disloyalty could result in their own arrest and execution; accordingly, allegations multiplied exponentially, creating a cascade of accusations that fed the expanding terror apparatus.

The NKVD, under the leadership of Nikolai Yezhov, transformed the purges into an industrialized process featuring quotas: regional authorities received instructions to arrest and execute specific numbers of "wreckers," "kulaks," and "anti-Soviet elements."

When regions fulfilled these quotas, Moscow demanded supplementary quotas, inflating the violence beyond the initial planned scope. The system became self-perpetuating and increasingly divorced from any rational security calculation.

The Operational Machinery: How Terror Consumed the State

The mechanics of the Great Terror reveal the systematic nature of Stalin's apparatus for mass violence. Operating Order 00447, issued by Yezhov on July 30, 1937, initiated the kulak operation targeting previously identified "social outcasts" including former wealthy peasants, unreliable elements, and potential counter-revolutionaries.

This order established a quota of 76,000 individuals for execution and 193,000 for ten-year imprisonment. However, regional and local NKVD officials, driven by a combination of fear and competitive zeal, continuously requested increases in quotas.

Over the sixteen-month operational period from August 1937 to November 1938, execution quotas expanded fivefold from initial estimates, reaching approximately 387,000 executions from 767,000 total convictions under this single order.

The extrajudicial tribunals known as troikas rendered verdicts within minutes, examining files and issuing death sentences without meaningful investigation or legal process.

These bodies consisted of local party, NKVD, and prosecutor representatives empowered to determine sentences of death or ten-year imprisonment. The speed of proceedings—often lasting mere minutes for complex cases—precluded any genuine examination of evidence.

Torture served as the primary investigative tool, with NKVD operatives inflicting extreme suffering to extract confessions implicating accomplices. Once extracted, these confessions triggered cascade arrests as accused individuals identified contacts, colleagues, and acquaintances to reduce personal suffering.

This system created mathematical inevitability: if every arrested individual under torture implicated an average of ten others, the terror expanded exponentially, limited only by the NKVD's physical capacity to process cases and carry out executions.

By 1938, the system had reached administrative saturation. The Politburo finally issued a decree in November 1938 criticizing NKVD "distortions" and abolishing the troikas, effectively terminating the peak phase of terror.

Even Stalin, by mid-1937, recognized the terror had become an unstoppable force consuming the state apparatus itself. The head of the NKVD, Yezhov himself, was arrested in 1938, charged with Trotskyite conspiracies, and executed—the revolutionary devouring its executioner.

The Devastation of Soviet Military Capacity

Perhaps the most strategically catastrophic consequence of the Great Purge was the destruction of Red Army leadership at precisely the moment when Nazi Germany remilitarized and moved toward aggressive expansion. Between 1937 and 1938, approximately 35,000 Red Army officers were purged from their positions.

Among the highest ranks, the devastation proved total: thirteen of the fifteen commanders of the Soviet Army were either executed or imprisoned, as were fourteen of the eighteen ministers of state.

Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, widely regarded as the most brilliant Soviet military strategist and a potential threat to Stalin's supremacy, was executed in 1937 along with seven other leading generals following secret trials lasting only hours.

The surviving officers were dominated by fear and demoralization. Junior officers and mid-level commanders understood that initiative, innovation, or any deviation from Stalin's directly issued orders risked interpretation as Trotskyite deviation or counter-revolutionary sabotage.

This created a paralysis of professional military judgment precisely when strategic flexibility became essential. The consequences manifested immediately in the Winter War against Finland in 1939–1940, where Soviet forces suffered humiliating losses against a numerically inferior opponent.

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the Wehrmacht's catastrophic early successes—destroying entire Soviet armies within weeks and capturing hundreds of thousands of prisoners—reflected not merely German military superiority but the fundamental structural weakness that Stalin's purges had inflicted upon Soviet command and control.

Millions of Red Army soldiers were killed or captured in the opening months of conflict, partly because experienced commanders had been eliminated and their replacements lacked the competence and confidence to execute effective defensive operations.

The irony remains profound: Stalin's paranoid elimination of potential rivals weakened the Soviet Union at the precise historical moment when maximal military strength became essential for survival against fascism.

The very officers Stalin feared as potential threats to his supremacy were precisely those who possessed the experience, training, and strategic acumen needed to confront Nazi Germany.

By destroying these officers, Stalin inflicted upon himself a self-imposed vulnerability that nearly proved fatal to the Soviet state.

Only the Soviet Union's vast manpower reserves, industrial capacity developed during the Five-Year Plans, and Hitler's own strategic miscalculations prevented Soviet collapse in 1941–1942.

Institutional Collapse and the Erosion of Trust

Beyond the military sphere, the purges generated comprehensive institutional breakdown throughout Soviet society.

The elimination of over half the Communist Party's Central Committee (78 of 139 members), combined with systematic removal of experienced administrators, industrial managers, and technical experts, created an administrative vacuum filled by individuals selected for political loyalty rather than competence.

Businesses and factories operated under conditions of terror, with workers and supervisors fearful that any deviation from targets or innovation in production methods could be interpreted as "wrecking"—sabotage in service of capitalist enemies.

Consequently, industrial production became characterized by risk-averse conformity rather than efficiency. The Soviet economy, already strained by collectivization and industrialization, suffered further disruption as paranoia replaced rational economic calculation.

The purges fundamentally transformed the nature of trust and hierarchy within Soviet institutions. The regime destroyed the possibility of collegial decision-making or policy debate.

Politburo members ceased raising objections to Stalin's directives, recognizing that dissent invited arrest and execution. Stalin's subordinates competed to demonstrate loyalty through increasingly harsh enforcement of purge orders and fervent affirmations of ideological orthodoxy.

The system that emerged was characterized by what Nikita Khrushchev later termed the "cult of personality"—the elevation of Stalin to a position above institutional constraint, where his word became law and his paranoid interpretations of events governed life-or-death decisions affecting millions.

The climate of fear permeated Soviet society at every level. Citizens lived with awareness that denunciation by neighbors, colleagues, or family members could result in arrest in the predawn hours and forced labor in the Gulag system.

The NKVD distributed quotas of denunciations, creating incentives for ordinary citizens to accuse others of political crimes regardless of evidence. Parents informed on children; children on parents; spouses on each other.

This systematic destruction of familial and social bonds undermined the informal networks of trust and reciprocity that permit societies to function. Soviet citizens developed psychological adaptations to perpetual danger—the practice of avoiding discussions, limiting associations, and performing absolute political conformity regardless of private beliefs.

Geopolitical Consequences: Soviet Weakness in the International Arena

The purges had immediate diplomatic consequences. France, observing the destruction of Soviet military leadership and the apparent chaos of Soviet politics, questioned the reliability of the Soviet Union as a military ally against Nazi Germany.

French leadership interpreted the purges as evidence either of profound internal instability within the Soviet system or of Stalin's irrational paranoia—both conclusions reducing confidence in Soviet capacity to fulfill alliance commitments. Germany, meanwhile, perceived Soviet weakness and became emboldened in its revisionist foreign policy.

Stalin's decision to negotiate the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany in August 1939 reflected partly the Soviet Union's weakened negotiating position.

At the moment when a unified anti-Nazi coalition might have constrained German expansion, Stalin instead sought a non-aggression pact granting Germany a free hand in Western Europe in exchange for Soviet neutrality.

The pact proved catastrophic for Soviet security; it enabled German rearmament and military buildup against the Soviet Union, while Stalin deluded himself that the agreement ensured Soviet safety.

When German invasion came in June 1941, Stalin initially refused to believe intelligence warnings from multiple sources, partly because his paranoid worldview interpreted warnings as deliberate misinformation designed to provoke Soviet–German conflict.

The dictator's psychological distortions, reinforced by years of purge-induced isolation and the elimination of advisors willing to contradict him, contributed to strategic miscalculation that nearly destroyed the Soviet state.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis

From Power Consolidation to Institutional Disintegration

The relationship between the purges and Soviet decline demonstrates a paradoxical causality: mechanisms ostensibly designed to strengthen Stalin's control over the state actually weakened state institutions and capacity.

This dynamic requires explanation. Stalin's fundamental problem was the persistence of alternative power centers and potentially independent actors within the Communist Party. The party apparatus represented the only institutional mechanism through which Lenin had exercised control, and Stalin inherited this organizational structure.

However, party membership included veteran revolutionaries with independent legitimacy, prior relationships with Lenin, and claims to ideological authority. These individuals could not be simply eliminated through administrative procedures but required some appearance of legal justification and ideological coherence.

The Kirov assassination provided Stalin with the pretext he needed to justify eliminating these individuals. However, the initial targeted purges of Trotsky's supporters and Zinoviev's faction necessarily expanded as more party members came under suspicion or provided denunciations to save themselves.

The logic became self-amplifying: each purge exposed new alleged conspirators, each of whom implicated additional individuals under torture, each revelation of new conspirators justified expanded purges. What began as targeted elimination of rivals evolved into systemic mass violence.

The structural contradiction emerged from the disconnect between the purges' stated purpose—eliminating foreign spies, saboteurs, and anti-Soviet conspirators—and the actual selection of victims.

The vast majority of purge victims were entirely innocent of any genuine conspiracy against the Soviet state. They were arrested because they belonged to social categories deemed suspect (former kulaks, bourgeois specialists, Old Bolsheviks), because they occupied positions that someone wished to acquire, or because they appeared on quota lists requiring fulfillment.

This fundamental disconnection between justification and reality meant that the purges could not achieve their stated purpose—the elimination of genuine threats—while simultaneously destroying the institutional capacity required for effective governance.

Contemporary Geopolitical Implications

The Modern Authoritarian Paradox

The patterns established during Stalin's purges retain remarkable relevance for contemporary understanding of authoritarian governance. Modern authoritarian regimes in China, Russia, and elsewhere employ purges as instruments of elite control and power consolidation, yet operate within a fundamentally different context than Stalinist totalitarianism.

Stalin's regime, whatever its brutality, possessed a unifying ideology in Marxism-Leninism and a powerful party apparatus capable of surviving Stalin's death. The system demonstrated sufficient institutional coherence to transform into Soviet-style governance under Nikita Khrushchev after Stalin's 1953 demise.

Contemporary authoritarians, by contrast, lack comparable ideological grounding. Xi Jinping's anti-corruption campaign in China, initiated in 2012 and continuing with intensifying scope, demonstrates purge mechanisms resembling Stalin's terror in scale but lacking coherent ideological justification beyond "eliminating corruption."

These purges serve primarily to eliminate potential rivals, consolidate Xi's personal power, and enable a shift toward "imperial presidency" unconstrained by party norms or institutional limits. Yet the campaign lacks the Marxist-Leninist theoretical framework that legitimized Stalinist repression and instead rests on contemporary populist anti-corruption sentiment. This removes one potential source of regime stability that the Soviet system possessed.

China's experiences reveal what scholars term the "Stalin logic": governance failures generate purges designed to reassert control, but purges eliminate competent administrators and create institutional paranoia that worsens governance, necessitating further purges.

The cycle accelerates as problems mount and purges deepen. Xi's military purges have removed experienced commanders and disrupted military hierarchies during a period when China faces intensifying strategic competition with the United States and faces potential Taiwan contingencies.

The creation of a military organization oriented toward loyalty to Xi personally rather than institutional professionalism mirrors Soviet experiences and creates similar vulnerabilities: competent officers become casualties of political struggle, strategic planning becomes subordinated to political considerations, and military effectiveness declines precisely when strategic challenges mount.

Russia under Vladimir Putin demonstrates similar patterns, though expressed through assassination and exile rather than mass terror.

Putin's elimination of oligarchs and media magnates who had accumulated power under Yeltsin, his orchestration of politically motivated prosecutions of potential challengers like Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and the assassination of journalists, opposition figures, and defectors signal ongoing efforts to eliminate alternative power centers.

Yet unlike the comprehensive party apparatus of Stalinist USSR, Putin's system depends on personal networks of intelligence officers and loyal oligarchs ("the siloviki," as Russian analysts term them).

The reliability of these networks remains perpetually uncertain, as Putin's paranoid style creates incentives for defection among elites and generates counterintuitive policies—such as the invasion of Ukraine—that alienate supporters and reduce regime stability.

Scholarly research on authoritarian regime stability identifies elite cohesion as the fundamental pillar of autocratic endurance. Regimes fracture when ruling elites defect, signaling regime weakness to potential challengers.

Purges intended to prevent elite defection paradoxically increase defection likelihood by creating uncertainty about whether the regime will honor promises to reward loyalty, whether competent administrators will be protected if they develop autonomous power bases, and whether survival requires demonstrating supreme loyalty through increasingly dangerous actions.

Elites with alternative options—private business interests, international connections, or autonomous military power bases—become more inclined to abandon the regime when purges create existential threats. The historical record demonstrates that purges signal authoritarian weakness to international observers and domestic populations, contrary to the intended effect of demonstrating regime strength.

Modern authoritarian regimes further lack the institutional mechanisms that allowed Stalinist USSR to maintain coherence despite terror. The Communist Party, despite its role in administering the purges, retained sufficient institutional apparatus to sustain Soviet governance.

Contemporary autocracies like Russia depend more on personalist patronage networks and military-security apparatus with less developed institutional depth. When Putin dies or loses power, the system lacks institutional mechanisms for succession that the Soviet system possessed.

This structural difference makes modern authoritarianism simultaneously more fragile and more prone to catastrophic miscalculation than Stalinist totalitarianism, despite technological and informational advantages that might appear to strengthen state control.

Future Steps

Patterns of Authoritarian Evolution and Geopolitical Risk

The contemporary trajectory of Chinese and Russian authoritarianism suggests intensifying reliance on purges as power-consolidation mechanisms. Xi Jinping's removal of potential successors, elimination of term limits, and increasingly comprehensive control of party and military institutions parallel Stalin's establishment of one-person rule.

However, the absence of unifying ideology and institutional continuity mechanisms creates instability. Economic pressures from demographic decline, slowing growth, and environmental challenges in China converge with military overextension and strategic competition with the United States to create conditions where governance failures accumulate.

Similarly, Russia's strategic overextension through the Ukraine invasion, combined with economic sanctions and international isolation, generates pressures that Putin's regime attempts to manage through enhanced internal repression, control of information, and occasional purges of blamed subordinates.

Yet the regime's narrower institutional base and dependence on oligarchic support make it more vulnerable to collapse if external circumstances deteriorate further. The pattern observed in historical analysis suggests that as conditions worsen, purges intensify, creating a vicious cycle where elite confidence declines and regime stability erodes.

The geopolitical implications warrant serious consideration. Weakened regimes prone to internal paranoia become less predictable and potentially more dangerous internationally, as leaders divert attention from domestic problems through external military adventures or crisis escalation.

The Ukrainian invasion partly reflected Putin's attempt to mobilize nationalist sentiment and distract from economic problems; similar dynamics could manifest in Chinese threat-making against Taiwan or Russian provocations in Eastern Europe. Authoritarian regimes experiencing internal decay may calculate that military victories provide legitimacy alternatives to economic performance or institutional legitimacy.

Furthermore, the structural inability of modern authoritarian regimes to tolerate dissent or alternative perspectives creates informational deficit regarding their own capacity and limitations. Purges eliminate not merely political rivals but also experienced administrators capable of providing accurate assessments of capabilities and constraints.

This creates potential for catastrophic miscalculation where leaders overestimate their capacity to achieve military or political objectives, leading to ventures with disastrous consequences. The Soviet experience with Afghanistan in the 1980s and the Russian experience with Ukraine suggest this pattern persists.

Conclusion

Historical Lessons for Contemporary Geopolitics

Stalin's Great Purge of 1936–1938 exemplifies the paradoxical logic of authoritarian power consolidation. Mechanisms ostensibly designed to eliminate threats and strengthen state control instead undermined institutional capacity, removed expertise, destroyed trust, and created psychological distortions that generated catastrophic strategic miscalculation.

The purges reflected not confidence in Stalin's rule but anxiety about its fragility and haunting awareness of alternative power centers and potential rivals.

By destroying much of the party apparatus and military leadership, Stalin achieved absolute personal power—but at the cost of weakening the state he ruled at the precise moment when existential threats emerged.

Contemporary authoritarian regimes operating in China and Russia employ similar mechanisms of purge-based power consolidation. Yet lacking the ideological coherence and institutional anchoring of Stalinist totalitarianism, they demonstrate even greater structural fragility.

The "Stalin logic" of worsening governance generating intensified purges, creating further governance failure, operates in contemporary authoritarianism without the compensating institutional mechanisms that enabled Soviet survival despite Stalin's terror.

For international strategists, scholars, and policymakers, the historical experience teaches several conclusions.

First, intensive purging by authoritarian regimes signals weakness rather than strength and should be interpreted as indicating underlying regime fragility.

Second, such regimes become increasingly prone to miscalculation as purges eliminate experienced advisors and create informational deficit about actual capabilities and constraints.

Third, the trajectory toward one-person rule lacking institutional constraints inevitably generates instability and succession crises that international competitors may exploit.

Fourth, authoritarian regimes weakened by internal purges demonstrate reduced capacity for sustained strategic competition while simultaneously increasing likelihood of desperate external adventurism.

Understanding these patterns permits more accurate assessment of geopolitical trajectories and potential for regime collapse or dangerous escalation. The history of the Soviet purges demonstrates that authoritarian consolidation through terror proves ultimately incompatible with institutional resilience, strategic competence, and regime durability.

This pattern suggests that contemporary authoritarian regimes, regardless of their apparent strength at any given moment, carry seeds of eventual instability rooted in the fundamental logic of personalistic rule unconstrained by institutional limits or ideological coherence.