What's Buried by Baghdad's Construction Boom: The Politics of Rebuilding in a City of Memories

Executive Summary

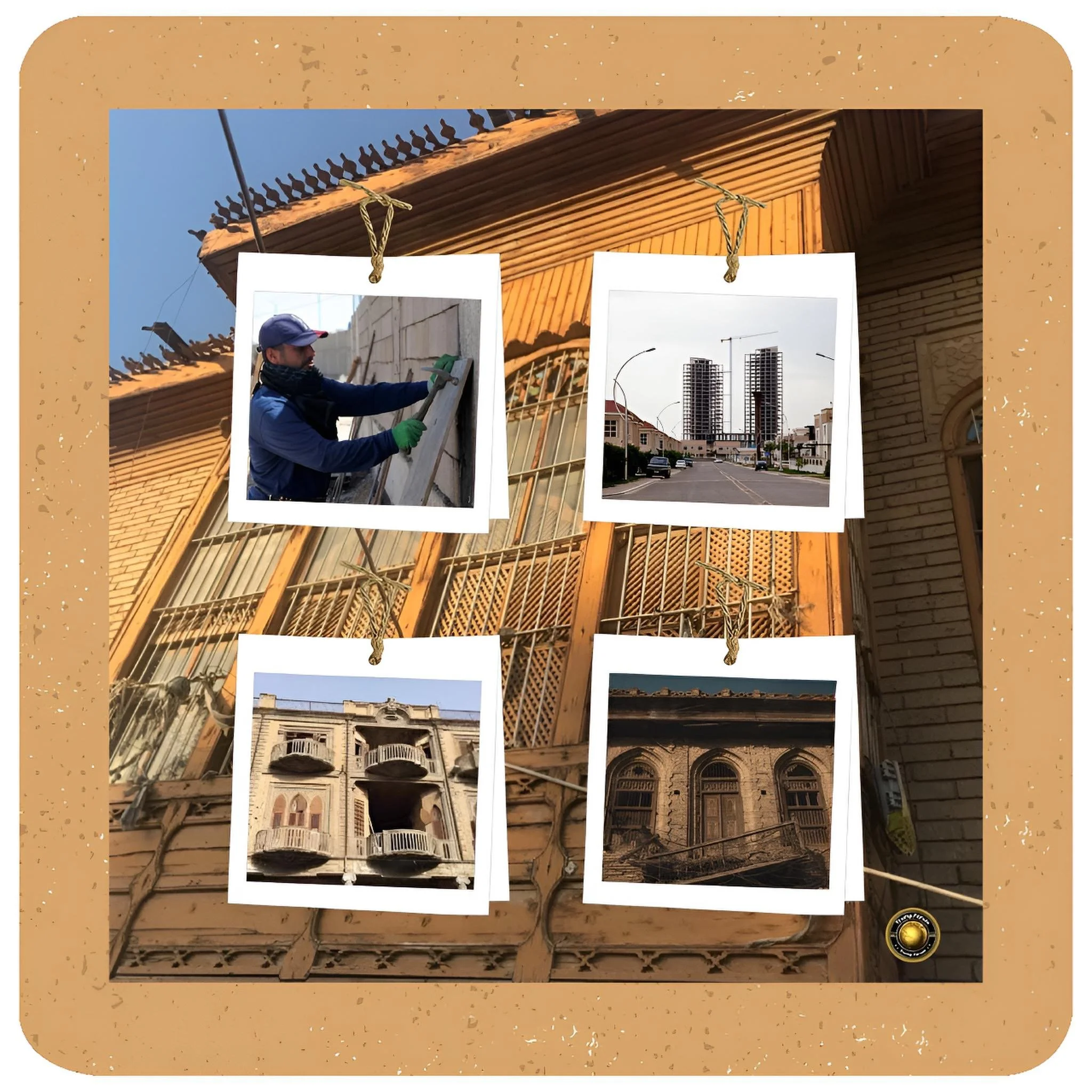

Baghdad's contemporary construction renaissance, marked by ambitious vertical development and large-scale urban renewal projects, simultaneously obscures and destroys the architectural and cultural patrimony that defines the city's identity.

The tension between modernization and heritage preservation reveals a fundamental paradox: while reconstruction activities nominally signal economic recovery and political legitimacy, they operate through mechanisms that systematically dismantle the layered historical narratives inscribed within the urban fabric.

FAF examines the political economy of Baghdad's construction boom, analyzing how speculative investment, development models imported from Gulf emirates, and fragmented urban planning have transformed the capital into a site where historical amnesia is literally built into commercial towers and residential complexes.

Introduction: The Archaeology of Forgetting

A visitor standing on a Baghdad street holding an architectural drawing faces an immediate and disorienting problem.

Without comprehensive contemporary mapping or preservation documentation, the buildings themselves become opaque. They do not announce their provenance, their architects' intentions, or the communities who once inhabited them. This is precisely the condition that confronts researchers seeking to recover Baghdad's Jewish neighborhoods, Ottoman commercial quarters, and modernist treasures. The inability to locate a single house from a family's nostalgic memory—despite possessing its architectural drawing—encapsulates a larger crisis: Baghdad's past is being systematically buried not by war alone, but by the very reconstruction that claims to herald the city's future.

Baghdad's architecture constitutes a palimpsest of extraordinary cultural and historical depth. Walking through the city one encounters art deco neighborhoods in advanced decay, a gymnasium designed by Le Corbusier according to principles developed from his engagement with Mediterranean and Modernist theory, a railway station constructed by British imperial architects who adapted subtropical climate expertise from the Indian subcontinent.

Mid-century modernism flourished here in a post-1958 revolutionary climate animated by oil revenues and cultural optimism. Walter Gropius and The Architects Collaborative planned Baghdad University. Iraqi architects of exceptional talent—Mohamed Makiya and Rifat Chadirji foremost among them—wove echoes of Abbasid and Mesopotamian formal vocabularies into rigorously modern but distinctly localized architectural languages. The city, in its architectural expression, was layered, fragile, and unlike anywhere else.

Yet across 2025 and 2026, this architectural inheritance exists under extraordinary pressure.

With housing shortages estimated between 2.5 and 3.5 million units, population growth at 2.6 percent annually, and construction projected to expand at five percent yearly through 2027, Baghdad is experiencing a building boom unprecedented since the immediate post-war reconstruction efforts.

This expansion is neither accidental nor politically neutral. It reflects the government's strategic prioritization of housing delivery, private sector appetites for speculative returns, and the importation of development models—predominantly Dubai-inspired commercial and residential towers—that systematically subordinate historical preservation to vertical density and real estate optimization.

Historical Foundations: Layers of Empire and Revolution

To understand contemporary destruction, one must first grasp what is being destroyed. Baghdad's founding in 762 CE by Caliph Al-Mansur established a city explicitly conceived as a political instrument and administrative center.

The Round City (Madinat al-Salam, "City of Peace") was constructed according to a circular geometry derived from ancient Persian urban planning traditions, with three concentric walls and four equidistant gates pierced to cardinal directions.

This was not organically evolved urban fabric but rather a calculated geometric statement about caliphal power and cosmic order. The city rapidly expanded beyond these initial boundaries, acquiring over centuries the dense, economically diverse neighborhoods that characterize medieval Islamic urbanism.

The Ottoman conquest in 1638 inscribed a new layer upon these structures. Under Ottoman administration, Baghdad became a provincial capital within a sprawling empire, its governance refracted through imperial bureaucratic structures. In 1916, Ottoman Governor Khalil Pasha ordered the construction of Rasheed Street, a 52-foot-wide thoroughfare designed to facilitate rapid military movement through the dense historic core.

The street's creation required massive demolition—existing structures were razed along a predetermined line, except for homes belonging to the politically influential. Though built to commemorate Ottoman military success at Kut al-Amara, Rasheed Street became most culturally significant during the British Mandate period and the early post-independence era, when it functioned as the city's primary cultural, intellectual, and commercial hub. Intellectuals, artists, and journalists congregated in its famous coffeehouses; it hosted cinemas, theaters, and the apparatus of modern public life.

The British Mandate (1917-1932) introduced a different architectural language and spatial logic. Early British administrators invested in infrastructure—roads, bridges, fixed structures replacing the floating crossing mechanisms that had historically connected the Tigris's banks.

This infrastructure facilitation enabled horizontal urban expansion. More significantly, the Mandate period witnessed the rise of art deco and modernist architecture, as Iraqi and international architects engaged with contemporary European design vocabularies.

The 1920s through 1950s produced neighborhoods of extraordinary stylistic sophistication, with brick facades employing decorative vocabularies derived from Islamic geometry and floral motifs, adapted to accommodate modern structural systems and climatic requirements.

The period following Iraq's independence in 1932, and especially after the 1958 revolution that overthrew the Hashemite monarchy, constituted a moment of cultural and economic optimism. Post-revolutionary governments, engorged by rising oil revenues, invited the world's most prestigious architects to reimagine the capital.

Le Corbusier accepted a commission to design a sports complex (initiated in 1956, eventually realized only partially between 1978 and 1980). Walter Gropius and The Architects Collaborative designed Baghdad University according to principles of functional modernism combined with allusions to Mesopotamian geometry.

Iraqi architects of profound philosophical conviction—most notably Mohamed Makiya and Rifat Chadirji—developed what might be termed a specifically Iraqi modernism, one that synthesized the formal and spatial innovations of European modernism with the architectural heritage of Abbasid Baghdad and Mesopotamian civilization.

Mohamed Makiya, trained in England at Liverpool University and Cambridge, returned to Baghdad in 1946 as one of the first formally credentialed Iraqi architects. He established the first department of architecture at Baghdad University in 1959 and created works that became canonical expressions of modernist aspiration tempered by historical consciousness.

His restoration and reconstruction of the Al-Khulafa Mosque (1960-1963) represents perhaps the most sophisticated architectural response to the question of how to honor medieval Islamic heritage while speaking authentically in a modernist idiom.

The original mosque, built in the 9th century by the Abbasid Caliph Al-Muqtafi, possessed a 13th-century minaret of extraordinary historical significance—the highest point in medieval Baghdad, still standing but now listing precariously. Makiya's intervention involved constructing a modernist mosque around this leaning minaret, using exposed concrete and brick to create what his son Kanan Makiya (the prominent scholar of Iraqi politics and art) describes as a "wall bay unit"—a thick wall articulated through the interplay of Kufic calligraphic frieze, traditional brickwork, and modern concrete and steel.

The minaret itself was protected, preserved, and monumentalized, not by historical recreation but by careful compositional arrangement that allowed the medieval structure to dominate while the modern structures provided respectful architectural frame.

This represented a model of modernization, of "Westernization" properly understood—not as erasure of historical identity but as synthesis, the production of something authentically new that honored antecedent traditions while speaking to contemporary needs and aspirations.

Current Status: The Construction Boom and the Problem of Scale

Beginning in the early 2020s and accelerating through 2025-2026, Baghdad entered a construction cycle of unprecedented intensity. After four decades of conflict, sanctions, and underinvestment, the city's building stock had deteriorated dramatically. War, occupation, sectarian violence, and economic collapse had destroyed or severely damaged vast residential areas.

The government's recognition of a housing shortage exceeding 2.5 million units created political pressure for rapid residential supply expansion. The solution, embraced by both public authorities and private developers, centered on vertical intensification: high-rise residential towers, predominantly concentrated in central Baghdad and along the airport road.

This is not incidental to Baghdad's circumstances. Iraq's population stands at approximately 46 million, with over 8 million concentrated in Baghdad. Growth exceeding 2.6 percent annually means demand for approximately 250,000 housing units per year simply to maintain existing per-capita supply.

The government's own housing initiatives have been plagued by delays, corruption, and funding gaps—65 percent of government housing projects initiated before 2023 were either abandoned or significantly delayed. Private developers, meanwhile, have proven more responsive to market signals. Since construction commenced at scale, property prices have begun declining, suggesting that supply expansion is producing some equilibrating effect.

Yet the manner and model of this expansion proves consequential. Developers have adopted what might be termed a Dubai paradigm: vertical towers prioritizing commercial returns, with minimal attention to urban integration, public space activation, or historical context.

Large residential complexes are being constructed with inadequate separation between towers, insufficient green areas, and poor building quality despite premium pricing. Utilities infrastructure—electricity, water, sewage, telecommunications—already strained under the burden of existing populations, has been overwhelmed by rapid densification. The Baghdad Municipality acknowledged that early planning decisions were "more or less random," with individual mayors designating sites for high-rises according to political or personal preference rather than comprehensive urban strategy.

Architectural heritage has not been explicitly targeted for destruction, but it has been subordinated to profit maximization in ways that amount to systematic elimination.

Parks and orchards that historically provided ecological buffers and recreational space have been transferred to private developers for conversion to residential complexes. Ottoman-era neighborhood structures, with their characteristic compact urban fabric organized around courtyards and winding streets, lack the economic productivity of vertical towers.

The market logic is relentless: a traditional courtyard house occupying significant land with modest economic return becomes rational for demolition and replacement with a high-rise yielding multiples of the original revenue.

Key Developments: Preservation Efforts and Political Negotiations

Paradoxically, the same government promoting intensive development has simultaneously undertaken heritage restoration projects. The most significant undertaking involves the historic central district, a collaboration among municipal authorities, the Central Bank of Iraq, and the Association of Iraqi Banks.

This project focuses specifically on Rasheed Street and adjacent Ottoman-era neighborhoods, particularly the districts surrounding the Al-Khulafa Mosque and historic commercial areas.

The reconstruction approach prioritizes facade restoration, targeting salt damage, moisture penetration, structural leaks, and other degradation resulting from decades of neglect and environmental assault.

The works aim to recreate buildings according to Islamic architectural principles, though engineers have confronted an unexpected obstacle: many of the original plans and archives from earlier restoration attempts were destroyed during the 2003 war. The project achieved approximately 80 percent completion by mid-2025, with formal reopening of Rasheed Street scheduled for September 2025.

The restoration itself emerged from an interesting political consensus. As contemporary historians note, after a devastating car bomb destroyed the street in 2007, "for once they all agreed—university, companies, state, municipality—to rebuild at all costs, and in less than two years the street was rebuilt more or less identically."

This underscores a crucial tension. Rasheed Street's reconstruction occurred not because authorities prioritized historical preservation in principle, but because the street's symbolic value as a cultural and commercial thoroughfare demanded restoration.

The commitment was temporary and circumstantial, animated by desire to repair visible urban damage and restore functional urban systems. It did not produce a comprehensive preservation framework or approach to architectural heritage as a whole.

The Al-Khulafa Mosque restoration presents a more complex case. The site represents a collision of historical layers: a 13th-century minaret built by the 36th Abbasid Caliph Al-Muqtafi, now in severe structural distress and listing perceptibly; and Makiya's 1960s modernist mosque, itself now regarded as a masterpiece of Iraqi architectural modernism worthy of preservation.

The restoration must therefore navigate between protecting a medieval Islamic monument and conserving a 20th-century modernist structure—both now designated as heritage, though they occupy different historical registers and represent different architectural traditions.

This multiplication of what requires preservation creates an unprecedented curatorial challenge. A single site contains Abbasid architectural heritage, Ottoman commercial structures, British colonial buildings, modernist civic monuments, and contemporary development pressures. Which layer deserves priority? Who decides? How do multiple constituencies with competing claims negotiate shared historical space?

Contemporary Scholars and the Problem of Development

The most trenchant critical voices articulating concerns about the construction boom come from architectural historians and heritage specialists.

Caecilia Pieri, a historian of 20th-century Baghdad and an expert on Arab modern heritage within UNESCO's World Heritage steering committee, has conducted fieldwork in Baghdad since 2003. Her documented observations are stark: "In Iraq, what destroys heritage is not war. It's reconstruction. The model of development in Iraq is Dubai: Towers, amusement parks, and malls. The rest seems less important."

This statement inverts conventional assumptions. It suggests that the explicit violence of military conflict, while devastating, operates differently from the violence of speculative development. Military destruction is recognized as catastrophic and therefore mobilizes rebuilding efforts.

Development destruction operates through market rationality and appears benign—it promises employment, housing, modernization. Yet the accumulated effect produces an urban landscape denuded of historical complexity and cultural specificity.

Kanan Makiya, the Iraqi-American scholar and son of architect Mohamed Makiya, echoes similar concerns in his work on Iraqi monuments and memory. He articulates what might be called the paradox of successful reconstruction: what is lost is a "meaningful, non-kitsch relationship to one's own past."

The city's identity comes from its accumulated layers, its visible testimony to multiple historical epochs coexisting in spatial proximity. High-rise towers designed according to international commercial standards, erected on sites that once hosted Ottoman bazaars or modernist civic buildings, create visual rupture. The city becomes, as Makiya notes, "a different city with the same name." It maintains the geographic designation and administrative continuity while losing the cultural and historical substance that once animated it.

These concerns are not conservative nostalgia for a past impossible to recover. Rather, they reflect recognition that urban landscapes constitute archives.

Buildings materialize historical consciousness; they carry traces of past communities, aspirations, technologies, and aesthetic commitments. When developers demolish a traditional courtyard house to construct a tower, they do not merely replace one structure with another. They erase the spatial logic that organized domestic life for centuries, the architectural knowledge embedded in thick walls and interior courtyards adapted to extreme heat, the social practices enabled by particular spatial configurations.

The Jewish Neighborhoods and the Specter of Vanished Communities

The contemporary construction boom's erasure becomes particularly acute when examined through the lens of Baghdad's Jewish history. The city hosted one of the world's most ancient Jewish communities, with documented presence extending to the Babylonian period following the destruction of the First Temple.

By the early 20th century, Baghdad's Jewish population constituted a vibrant, economically significant, and culturally productive community. The population peaked at approximately 180,000 in the early 20th century, concentrated in specific neighborhoods and integrated into the city's commercial, intellectual, and social life.

The community began its departure in the early 1950s following bombings whose perpetrators remain historically contested. Between 1950 and 1951, a process termed "sant al-tasqit" (the year of the tasqit) witnessed the departure of approximately 120,000 Iraqi Jews, primarily for Israel. Those who remained faced intensifying pressure following the 1958 revolution and particularly under the Ba'ath regime, which came to power in 1968. Public executions of accused spies in 1969, many of whom were Jewish, created a climate of terror. By 1971, the last substantial cohort of Iraqi Jews departed, culminating a 2,500-year presence in the region.

The neighborhoods they inhabited, now substantially deteriorated through decades of neglect and damage, house the memories of this vanished community.

A researcher seeking Isaac Amit's childhood home, last inhabited in 1971 before his family fled Iraq, must navigate streets where buildings are largely indistinguishable, where records are fragmented or lost. The house that Amit remembered perfectly—every corner familiar from childhood—has become archaeologically occluded, lost among dozens of similarly deteriorating structures.

This situation encapsulates the construction boom's paradox. The neighborhoods where Baghdad's Jewish community resided are precisely those now targeted for intensive redevelopment. As private developers and government authorities designate central districts for high-rise reconstruction, the physical structures that once housed this community face demolition or radical alteration.

The memory of the community becomes increasingly difficult to recover, archive, or commemorate. The buildings themselves—modest courtyard houses, commercial structures, synagogues—constitute a material record of the community's existence. Their destruction erases this record.

The larger question becomes: who is authorized to remember Baghdad? Whose historical narratives are embedded in the city's architectural form? Contemporary authorities promoting rapid reconstruction may have little interest in preserving structures associated with communities whose departure from Iraq was politically contentious and remains ideologically freighted.

The absence of institutional mechanisms for historical recovery or memory preservation means that deliberate historical erasure need not involve deliberate action against specific structures—it occurs through the invisible hand of market forces and private interest.

Cause and Effect Analysis: The Political Economy of Forgetting

Several causal mechanisms operate to produce the subordination of heritage to development. Understanding these mechanisms illuminates why preservation requires not merely good intentions but structural institutional change.

First, the sheer magnitude of the housing shortage creates political urgency that overrides other concerns. Governments derive legitimacy from demonstrable success in addressing immediate needs—housing, employment, basic services.

A family without adequate shelter does not benefit from the preservation of Ottoman architecture. Ministers facing pressure to deliver housing units have rational incentives to accelerate construction through density, height, and rapid permitting rather than through slower processes incorporating archaeological survey, heritage assessment, and community consultation. The political calculus favors speed over preservation.

Second, the development model itself—imported from Gulf commercial centers and amplified by international real estate capital flows—systematically privileges certain types of projects. High-rise residential and mixed-use commercial complexes generate returns that can service debt and provide investor exits within relatively short timeframes.

Historic preservation, by contrast, typically involves lower profit margins, longer capital recovery periods, and complications introduced by structural remediation and regulatory constraint. In the absence of conservation easements, heritage tax incentives, or mandatory preservation requirements, the market logic directs capital toward new construction rather than adaptive reuse or restoration.

Third, institutional capacity for heritage preservation remains limited. The Baghdad Municipality has engaged in some restoration work, but this reflects ad-hoc coordination rather than systematic policy. UNESCO-trained specialists like Caecilia Pieri can document what exists and advocate for its preservation, but they command no regulatory authority.

The Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities theoretically exercises stewardship over heritage sites, but the ministry's authority is often subordinate to Development and Housing ministries when land use decisions are contested. Without comprehensive heritage inventories, clear designation of protected structures and districts, and enforcement mechanisms with genuine teeth, preservation remains aspirational.

Fourth, the construction boom has benefited from technical innovations and foreign investment flows that privilege certain development models. South Korean firms, Emirati developers, and international architectural practices have brought capital and expertise to Baghdad. These actors naturally promote the development models with which they are familiar—the Dubai prototype, the Korean mixed-use complex, the international hotel tower. Iraqi architects and planners, while technically skilled, have been partially sidelined in favor of international firms, leading to a homogenization of design vocabulary across projects.

The particularity of Iraqi architectural tradition—the Makiya synthesis of Abbasid heritage with modernism, the Chadirji engagement with local environmental and cultural conditions—becomes less visible compared to internationally fungible design languages.

Fifth, the fragmentation of authority complicates preservation. Baghdad's reconstruction involves public authorities at municipal, provincial, and national levels; private developers of varying sophistication and integrity; international consultants; international financial institutions; and civil society organizations with limited formal power.

This fragmentation creates opportunities for developers to exploit jurisdictional gaps and regulatory ambiguity. A developer can acquire a site, accelerate permitting through political connections, and complete demolition and construction before heritage or neighborhood advocates can organize effective response.

Latest Concerns and Emerging Issues

By late 2025 and early 2026, several concerning developments have crystallized around the construction boom.

First, the infrastructure strain has become acute. Large residential complexes built in rapid succession have overwhelmed water, electrical, and sewage systems. In a city already experiencing severe water scarcity—Baghdad endured its driest season since 1933 in 2025, with the Tigris experiencing a 27 % decline in water levels from historical norms—the addition of hundreds of thousands of new residents without commensurate investment in water infrastructure creates unsustainable conditions.

Apartments constructed at premium prices lack reliable electricity and water supply, creating social tension and discrediting the development model even among those initially sympathetic to rapid construction.

Second, housing affordability has deteriorated despite supply expansion. While property prices have declined modestly, individual units remain extraordinarily expensive—houses regularly priced above $500,000 with little transparent justification. Government subsidized or concessional loan programs have had limited impact, with loan availability itself restricted by budget constraints and political disputes.

The housing shortage remains primarily a crisis of affordability rather than absolute shortage, yet the development model does not address this underlying problem. Much new construction targets mid-to-high income buyers, leaving low-income populations with housing conditions deteriorated by decades of underinvestment.

Third, environmental degradation associated with construction has accelerated. Archaeological sites remain unsurveyed as dozers clear ground. Protective riparian vegetation along the Tigris has been cleared for development.

The pollution resulting from unregulated construction activity compounds existing water quality problems. The paradox is that while Iraq's government has committed to environmental sustainability through frameworks like the 2023-2030 National Environmental Strategy, actual construction practices remain substantially unregulated.

Fourth, the political fragmentation that enables development also prevents coordinated heritage preservation. Different constituencies—government authorities, private developers, international actors, heritage advocates, neighborhood residents, academic institutions—lack mechanisms for genuine negotiation.

Heritage preservation becomes something pursued through individual projects and heroic efforts by committed specialists rather than systematic policy. The Rasheed Street restoration succeeded partly because its symbolic importance commanded consensus, but this exception proves the rule: most heritage sites lack such political salience.

Future Steps: Toward Integrated Urban Stewardship

Addressing the heritage crisis that accompanies the construction boom requires multi-scalar intervention.

At the immediate project level, Baghdad's authorities should mandate archaeological and heritage survey before permitting any major development in historic districts. Such surveys should occur sufficiently early to influence site selection and design, not merely to document what will be lost.

The Central Bank of Iraq's financing of the Rasheed Street restoration could serve as a model for financial mechanisms that align banking interests with heritage preservation—the restoration enhanced the cultural value and prestige of a major urban thoroughfare in which banking institutions maintain significant interests.

At the urban planning scale, Baghdad requires a comprehensive heritage preservation ordinance designating protected structures, historic districts, and conservation zones, with associated development restrictions and incentive mechanisms.

The planning framework should articulate explicit hierarchy of urban values: some sites prioritize housing delivery, others prioritize heritage preservation, still others seek integration of both objectives through adaptive reuse and sensitive infill development. Such planning should occur through genuine public deliberation involving heritage specialists, neighborhood residents, developers, and municipal authorities.

Institutional capacity must be strengthened. The Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Antiquities requires adequate budget and regulatory authority to function effectively. International partnerships—with UNESCO, with national heritage agencies, with academic institutions—should support training programs for conservation architects and urban planners.

The Rifat Chadirji Archives, housed at the Arab Image Foundation, should be digitized, analyzed, and made accessible to Iraqi architects and researchers. The documentation of Baghdad's architectural heritage—particularly its modernist structures—should be recognized as urgent.

The political economy of development requires modification. Heritage tax incentives can align private interest with preservation objectives. Conservation easements can allow developers to monetize historic structures while ensuring their preservation.

Public-private partnerships can distribute the costs of adaptive reuse among municipal authorities, preservation organizations, and private investors. The model should not be simply preservation as constraint upon development, but rather development that incorporates heritage stewardship as integral objective.

Critically, the voices of displaced and marginalized communities—particularly those whose neighborhoods are being razed or substantially transformed—should be centered in planning processes.

The Jewish communities whose former neighborhoods now face redevelopment, the lower-income populations being displaced by rising property values, the longtime residents of traditional neighborhoods witnessing rapid transformation—these constituencies should have institutional voice in decisions about their neighborhoods' futures.

Conclusion

Memory, Power, and the City

Baghdad's construction boom illuminates a paradox at the heart of urban modernization. Authorities promote reconstruction and development as signs of progress, normalization, and recovery from conflict.

Yet the mechanisms through which this reconstruction proceeds systematically erase the historical and cultural complexity that gives the city its distinctive identity.

What is constructed is certainly newer, often more efficient, sometimes more lucrative. But what is destroyed—the layered testimony to centuries of human habitation, to architectural innovation, to the presence of vanished communities—cannot be easily recovered.

The fundamental problem is not that Iraqis build too much or too fast, but rather that the institutional frameworks, planning cultures, and economic incentives governing development have been severed from any serious engagement with historical consciousness.

A different Baghdad is being built, as Kanan Makiya observes, and it will have the same name but a different character. This is a political choice, not an inevitable historical force.

Recognizing this as a choice opens the possibility of alternatives. A Baghdad that grows and modernizes while honoring its past is conceivable. It would require investment in heritage preservation infrastructure, meaningful integration of conservation objectives into planning processes, and political commitment to valuing historical continuity alongside rapid development. It would require listening to the voices of historians, architects, and residents who understand what is being lost. It would require accepting that some sites matter enough to develop slowly, thoughtfully, and in dialogue with historical context.

The buildings standing today constitute an inheritance from previous generations. How Baghdad's current authorities treat this inheritance—whether it is preserved, adapted, or systematically demolished for maximum commercial return—constitutes a statement about what this generation values and what it will bequeath to those who come after.

The stakes are not merely aesthetic or nostalgic. They concern the possibility of maintaining meaningful continuity with one's own past, of inhabiting a city whose physical form carries traces of its own history.

In erasing Baghdad's architectural patrimony, the current construction boom risks creating a city that is modern but rootless, efficient but culturally impoverished—a different city with the same name.