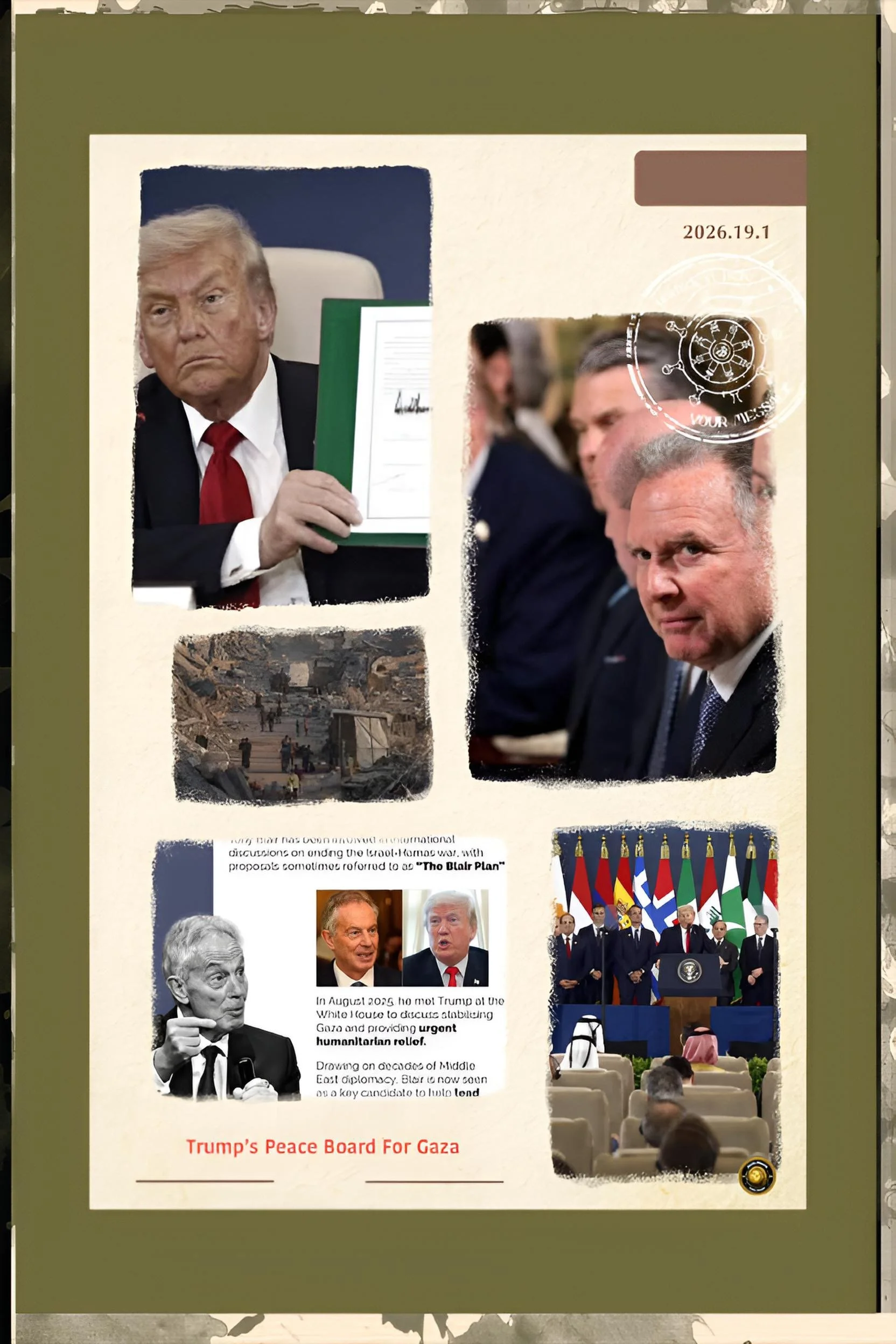

Who Really Runs Peace? Understanding Trump’s New Gaza Plan in Simple Terms

Summary

Imagine a city that has been bombed for years. Buildings are destroyed, families are broken, and almost everyone is exhausted. Now imagine that someone far away says, “I will create a new team to fix this city, and I will be the boss of that team.” That, in simple terms, is what Trump is trying to do with Gaza.

His idea has three main parts.

First, there is a ceasefire agreement that stopped most of the shooting and bombing.

Second, there is something called the “Board of Peace” that he wants to lead.

Third, there is a group of Palestinian experts—a technocratic committee—that will handle daily life in Gaza, like water, electricity, health, and schools.

Let us start with the Board of Peace.

Think of it as a club of powerful countries and famous people. Trump has invited leaders from many countries to join this club. Some of them, like Hungary and Vietnam, have said yes. Others are unsure.

To become a “founding member” forever, some countries are reportedly asked to pay a very large amount of money—about one billion dollars—to help rebuild Gaza.

In return, they get a permanent seat in the club. It is a bit like paying a huge membership fee to join an exclusive private club that claims it will help run a damaged city.

Trump will chair this board for life. That means he wants to be in charge of it as long as he is alive, not just while he is president. The board will not only deal with Gaza but may also work on other conflicts later. Some people see this as creative leadership. Others see it as one man trying to build his own mini‑United Nations.

Next, there is the technocratic committee in Gaza. “Technocratic” just means that the members are chosen because of their skills, not because they are leaders of political parties.

They are supposed to be experts—like engineers, doctors, financial planners, and administrators.

This committee, led by a Palestinian figure named Abdel Hamid Shaath, will run everyday affairs in Gaza. Imagine a team of professional managers running a city instead of politicians. That is the idea.

But there is a catch: this technocratic committee does not work on its own. It must operate “under the leadership” of the Board of Peace.

In other words, the experts in Gaza will still take direction from the foreign‑chaired board. To many Palestinians, this feels like their house is being managed by outsiders who hold the keys.

Now comes the hardest part: disarming Hamas.

In phase two of the ceasefire plan, Hamas and other armed groups in Gaza are supposed to give up their weapons. The plan says that all “military and offensive infrastructure” should be destroyed or made useless.

This includes rockets, tunnels, and other weapons. In exchange, Israel is supposed to pull its army out of Gaza, and an international peacekeeping force or reformed Palestinian security forces would take over.

On paper, this sounds neat and tidy: Hamas disarms, Israel leaves, peacekeepers arrive, technocrats run the place, and the Board of Peace oversees everything. In real life, it is much messier.

First, Hamas has not agreed to give up all its weapons. Imagine telling a group that has fought for years, “Lay down your guns, trust your enemies, and let outsiders protect you.” It is not hard to see why they hesitate.

Reports suggest that Hamas might be willing to get rid of some heavy weapons, like long‑range rockets, but not the guns that keep its fighters in control on the streets.

Second, Israel is not yet pulling out completely. Israeli forces are still inside large parts of Gaza. Some Israeli officials are already talking about what they will do if Hamas refuses to disarm.

They are making backup military plans. This tells you that even the people who signed the agreement do not fully believe that phase two will go smoothly.

Third, many countries do not want to send their soldiers into Gaza as peacekeepers.

It is dangerous, complicated, and politically risky. So even though the plan talks about an international force, nobody has firmly said, “We will send our troops.”

On top of all that, there is a deep trust problem.

Many Palestinians see the Board of Peace as a foreign body full of people who support Israel.

They worry that the technocratic committee is just a mask, and that real decisions will be made in Washington or other foreign capitals.

One Palestinian might say, “You call it a board of peace; I call it a board of control.” Human rights groups compare this setup to old colonial times, when powerful countries ran weaker territories “for their own good.”

Let us use a simple example. Imagine your neighborhood was destroyed by a fire. Instead of your town council and neighbors deciding how to rebuild, a group of rich people from another country forms a “Rebuild Committee.”

They tell you: “We will pay, we will choose your local managers, we will decide which houses get rebuilt first, and one of us will lead the committee forever.”

Some people might accept because they are desperate and need help. Others might say, “Wait, why are you in charge of my neighborhood?”

That is the emotional reality in Gaza right now.

So what happens next? In the coming months, this new Palestinian technocratic committee will try to run daily services.

The Board of Peace will meet, make statements, and try to raise money. Israel will watch closely to see whether Hamas makes any real moves to disarm.

Hamas will watch to see whether this plan is just another way to push them out without giving them anything in return.

Ordinary people in Gaza will watch to see whether their lives actually improve—whether electricity returns, homes are rebuilt, schools reopen, and they have some say in their future.

The best‑case scenario is that guns slowly fall silent, services improve, and the technocrats become trusted enough that people feel they have a stake in the new order.

The worst‑case scenario is that the plan collapses: Hamas keeps its weapons, Israel resumes heavy strikes, the Board of Peace becomes a talking shop, and Gaza remains trapped in a cycle of war and outside control.

In short, Trump’s Gaza plan is big, bold, and risky. It tries to replace chaos with a clear structure, but it also puts a great deal of power in the hands of outsiders.

Whether it will bring real peace or just a new kind of tension depends on what the people with guns—and the people under the rubble—decide to do next.