Nvidia's Blackwell Platform and the Competition: Strategic Analysis of Dominance, Threats, and Long-Term Market Positioning

Executive Summary

How Nvidia Will Win Despite Real Competition: The Strategic Architecture of Sustained Dominance in the AI Accelerator Wars

NVIDIA's dominance in AI accelerators, evidenced by its eighty-five to ninety-two percent market share in discrete GPU sales, faces multifaceted competitive challenges as of January 2026 that demand strategic analysis and forward assessment.

The emergence of AMD's MI350 and MI355X architectures, coupled with intensified custom silicon development by hyperscalers including Google, Amazon, and Meta, represents the most significant competitive threat since Nvidia established GPU computing supremacy in 2010.

Yet despite these challenges, the company's long-term strategic positioning appears substantially more resilient than market discussions acknowledge.

FAF analysis examines the specific competitive threats to Nvidia's Blackwell platform and the company's integrated strategic approach to sustaining market leadership through 2030 and beyond.

The fundamental conclusion is that Nvidia's competitive advantage rests not on any single technological innovation but on a nineteen-year accumulation of a software ecosystem, integrated full-stack systems design, and an orchestrated annual release cadence that competitors remain structurally incapable of replicating.

Introduction

From Monopoly to Oligopoly - The Evolution of AI Accelerator Competition

The competitive landscape for AI accelerators has evolved substantially since Nvidia emerged as the dominant GPU provider following the 2012 deep learning revolution. For over a decade, Nvidia faced minimal serious competition.

AMD's GPU business, though technically sound, suffered from an immature software ecosystem and customer inertia. Intel, despite its manufacturing prowess, failed to establish credible alternatives to Nvidia's architectures. Smaller competitors and startups pursued specialized niches but lacked the resources to compete with Nvidia in its core markets.

This competitive torpor enabled Nvidia to establish extraordinary market dominance. By 2024, the company controlled over 90% of the data center GPU market and commanded even greater shares in specific applications, such as generative AI training.

Yet this dominance, while apparently durable, has always rested on assumptions about competitive evolution and market structure that warranted skepticism. The CUDA ecosystem, while extraordinarily valuable, remained proprietary and under the control of a single vendor.

The superior performance of Nvidia's architectures, while consistent, was the result of engineering excellence rather than physical law. The switching costs preventing customer migration to AMD or other alternatives were real but fundamentally economic rather than technical.

Most importantly, Nvidia's market position rested on the contingent assumption that potential competitors would remain less capable or less motivated than Nvidia to invest in challenging its supremacy.

As of January 2026, these assumptions are under mounting pressure from multiple competitive vectors. AMD has released genuinely competitive products. Hyperscalers have committed billions of dollars to developing custom silicon.

Geopolitical export restrictions have fragmented markets, creating opportunities for alternative suppliers. Industry maturation has improved the quality of the software ecosystem on non-NVIDIA platforms.

While Nvidia maintains its market dominance, the nature of that dominance has subtly but fundamentally transformed: the company no longer competes in a landscape of minimal competitive intensity but instead operates in an increasingly multipolar competitive environment where maintaining leadership requires not technological inevitability but rather strategic excellence.

History and Current Status: The Competitive Landscape of January 2026

The Competitive Landscape of January 2026: AMD's Challenge, Intel's Margin, and Hyperscaler Custom Silicon

AMD's Challenge and Market Positioning

Advanced Micro Devices emerged as a serious GPU competitor in 2023 with its MI300 architecture, but achieved genuine competitive parity only with the 2025 release of the MI350 and MI355X architectures. The MI355X represents the first direct assault on Nvidia's Blackwell specifications with credible technical merit.

The chip contains 288 gigabytes of HBM3E memory, substantially exceeding Blackwell B200's 192 gigabytes. The memory bandwidth of eight terabytes per second matches Blackwell's capability, yet the additional capacity enables AMD to address what industry participants identify as the industry's most pressing bottleneck: the memory wall constraining inference workload performance.

More significantly, AMD achieved this competitive performance by adopting TSMC's three-nanometer process node for MI355X compute chiplets, compared to Nvidia's four-nanometer-plus Blackwell process. This process advantage provides AMD with theoretical performance-per-watt superiority.

Native support for ultra-low-precision FP4 and FP6 datatypes in MI355X hardware provides feature parity with Nvidia's Blackwell, which emphasizes low-precision inference optimization. Independent analyses suggest that MI355X delivers performance-per-dollar advantages for specific inference workloads, positioning AMD as a cost-conscious alternative for hyperscalers willing to absorb the costs of transitioning to the software ecosystem.

Yet despite these genuine technical achievements, AMD's market share has grown only marginally. As of January 2026, AMD controls approximately five to eight percent of the AI accelerator market, up from near-zero two years prior. This limited market penetration, despite Nvidia's technical competitiveness, reflects the severity of Nvidia's software ecosystem advantage.

Customers evaluating AMD hardware confront substantial switching costs: developers trained exclusively in CUDA must acquire new expertise; software optimizations laboriously accumulated over years of Nvidia development must be replicated; production-tested code must be rewritten for ROCm compatibility; and organizational dependencies on CUDA-specific tools and libraries must be rearchitected.

The Stack Overflow evidence is stark: there are 50 times as many CUDA questions as ROCm questions, despite ROCm's 9-year history and AMD's substantial R&D investment.

This ecosystem gap explains AMD's strategic positioning as a cost-focused alternative rather than a performance leader. For hyperscalers with the resources to absorb migration costs and dedicated engineering teams to support custom optimization, AMD presents a viable option. For enterprises, startups, and smaller organizations, the switching costs exceed the performance or economic benefits.

AMD's rational approach has become to compete for specific market segments where ecosystem dependency is less binding—traditional HPC workloads, customers with existing AMD relationships, and inference-heavy operations amenable to custom optimization—rather than attempting to displace the ecosystem across the broader market.

Intel's Marginal Position

Intel's Gaudi 3 accelerator, released in 2024, occupies a peculiar competitive position: it possesses technical strengths in specific, narrow dimensions yet fails to achieve meaningful market traction. Gaudi 3 delivers BF16 matrix performance roughly equivalent to Nvidia's H100 architecture and claims price-performance advantages of two to three times over contemporary Nvidia hardware. On high-throughput inference workloads, testing with commodity models like Llama and Gaudi 3 delivers competitive results.

Yet independent testing reveals far more sobering competitive positioning. When subjected to demanding inference tasks on larger models—specifically Llama 3.1 405B testing conducted by Los Alamos National Laboratory in partnership with Aquatron—Nvidia's H200 GPU outperformed Gaudi 3 by approximately nine times.

This massive performance gap, despite Gaudi 3's claimed advantages on simpler benchmarks, reflects the architecture's limitations for complex reasoning and inference workloads, which are increasingly central to production AI systems.

Intel's strategic response has been candid: company executives have explicitly acknowledged that Gaudi 3 does not match Nvidia's flagship offerings in head-to-head performance. Instead, Intel has repositioned Gaudi 3 as a cost-effective platform for task-based models and open-source inference on smaller architectures suitable for enterprise workloads with limited performance requirements.

This positioning—economical rather than performance-leading—represents Intel's acknowledgment of Nvidia's overwhelming superiority on capability metrics. Intel maintains the objective of competing in the AI accelerator market but has lowered expectations for capturing small market segments where cost matters more than performance.

Custom Silicon and Hyperscaler Strategies

The most significant competitive threat to Nvidia's dominance emerges from hyperscalers' investments in custom application-specific integrated circuits. Google's Tensor Processing Unit, now in its seventh generation (Ironwood), delivers exceptional performance for Google's internal AI workloads, including Gemini and AlphaFold.

The TPU possesses two critical characteristics: first, extraordinary optimization for Google's specific use cases; second, complete unavailability for external purchase. Google has maintained TPU exclusivity, deploying the chips internally while offering GPU-based alternatives to Google Cloud customers seeking Nvidia compatibility.

Recently, this strategic positioning has evolved. Meta has reportedly entered negotiations to purchase TPUs from Google Cloud beginning in 2026, representing the first significant external deployment of TPU technology outside Google's immediate control. This development signals that custom ASIC maturation has progressed sufficiently that leading AI firms perceive utility in adopting specialized hardware from technology-capable peers.

Amazon's Trainium and Trainium2 architectures, now in their third generation and available for general deployment, represent similarly specialized hardware optimized for training Amazon's Claude models. AWS claims thirty to fifty percent cost reductions compared to GPU-based training, a figure that would justify substantial custom silicon investment if sustainable at hyperscale volumes.

Yet the economics and timelines of custom ASIC development constrain their competitive threat to narrowly defined hyperscaler contexts. Designing a competitive custom accelerator requires upwards of $20 million in non-recurring engineering expenses, coupled with 12 to 24 months of design cycles before production systems become available.

By the time custom silicon reaches production, market requirements have frequently shifted, underlying models have evolved, and—critically—Nvidia has released new generations, rendering the custom silicon development outdated. This generational competition dynamic creates acute risk for custom ASIC investments: a multi-million-dollar engineering effort can turn into a "paperweight" if market conditions or Nvidia's technology trajectory shift unexpectedly.

These realities constrain the economics of custom ASICs to mega-hyperscalers operating at such extraordinary scale that the return on investment justifies the engineering costs and the obsolescence risk. For Google, operating at one exawatt-plus scale with internally developed Transformer architectures and proprietary workload patterns, TPU development proves economically sound.

For Amazon, processing hundreds of millions of inference requests daily through its infrastructure, Trainium economics justify the investment. For Meta, optimizing recommendation engines processing billions of queries daily, custom silicon specialization creates measurable value.

For the broader market—enterprises, startups, smaller cloud providers, and even mid-scale technology companies—the economics of custom silicon development prove untenable. The upfront costs and risk must be amortized across insufficient volume.

Current Market Dynamics and Nvidia's Maintained Dominance

Despite these competitive challenges, Nvidia's market position has strengthened rather than weakened through 2025 and into 2026. Blackwell architectures remain completely sold out through mid-2026, with customers placing orders for systems they will not receive for 18 to 24 months.

The company's shift to an annual architecture release cadence—moving from biennial releases characteristic of previous generations—has proven devastatingly effective at preventing competitive catch-up. Just as competitors begin shipping products competitive with Nvidia's current flagship architecture, the company transitions to next-generation systems, rendering competitors' products relatively obsolete.

Hyperscalers face capacity constraints driven by Nvidia's overwhelming demand. Chinese technology companies alone placed orders for over two million H200 units in 2026, exceeding Nvidia's current inventory by nearly three times. This demand-supply imbalance, while seemingly problematic, actually reinforces Nvidia's competitive advantage.

Customers cannot wait for AMD alternatives to mature or custom ASIC programs to complete; they require compute capacity immediately. NVIDIA's supply constraints paradoxically strengthen customer lock-in by forcing customers to accept whatever NVIDIA can deliver while indefinitely deferring diversification plans.

Key Developments: Strategic Advantage Through Ecosystem, Integration, and Roadmap

The CUDA Fortress, Full-Stack Integration, and the Annual Release Cadence as Strategic Weapons

The CUDA Ecosystem as Durable Competitive Moat

The fundamental source of Nvidia's competitive resilience, often underappreciated in technology discourse, is not superior semiconductor engineering but rather nineteen years of accumulated software ecosystem development. CUDA, launched in 2006, created the first practical framework for general-purpose GPU computing.

Over the subsequent two decades, this ecosystem has accumulated extraordinary depth: over 2 million registered developers, 3,500 GPU-accelerated applications, and 600 CUDA-optimized libraries. Collectively, this ecosystem represents billions of dollars of sunk investment in Nvidia-specific optimization and development.

The competitive significance of this ecosystem depth proves difficult to overstate. A developer proficient in CUDA does not merely choose Nvidia hardware; they have structured their professional expertise around CUDA-specific knowledge. An organization that has deployed CUDA-optimized code across production systems has invested substantial engineering effort in validating and optimizing it.

A researcher publishing findings validated on CUDA hardware has created evidence that their methods work on Nvidia infrastructure. These accumulated dependencies create switching costs exceeding the performance or economic advantages of alternative platforms.

AMD's ROCm ecosystem, launched in 2016 with the explicit intent to challenge CUDA dominance, illustrates the challenge of ecosystem displacement.

Despite nine years of development and AMD's substantial R&D investment specifically in ROCm maturation, the platform remains dramatically inferior to CUDA in functional breadth, application depth, and developer familiarity. Stack Overflow data reveals fifty times more CUDA questions than ROCm questions—a metric suggesting relative developer community size and engagement. Migration from CUDA to ROCm incurs ten to twenty percent performance regression despite AMD's hardware specification advantages.

Platform migration requires 6 to 12 months per organization, involving CUDA kernel rewrites, substitutions of cuDNN with the MIOpen library, developer retraining, and toolchain changes.

AMD's strategic response has been sophisticated: the company has not attempted to replace the ecosystem but rather to coexist with it. ROCm development targets specific domains where ecosystem switching costs prove lower—traditional HPC applications, organizations with prior AMD relationships, and inference-specific workloads amenable to isolated optimization.

This bifurcation strategy can achieve a moderate market share in specific segments but cannot displace CUDA's dominance. The economic incentive structure prevents AMD from closing the ecosystem gap: achieving ecosystem parity with CUDA would require sustained above-parity R&D investment (relative to AMD's size) while accepting below-parity financial returns until critical mass develops.

Quarterly earnings pressure and investor expectations make such a long-term strategic sacrifice untenable.

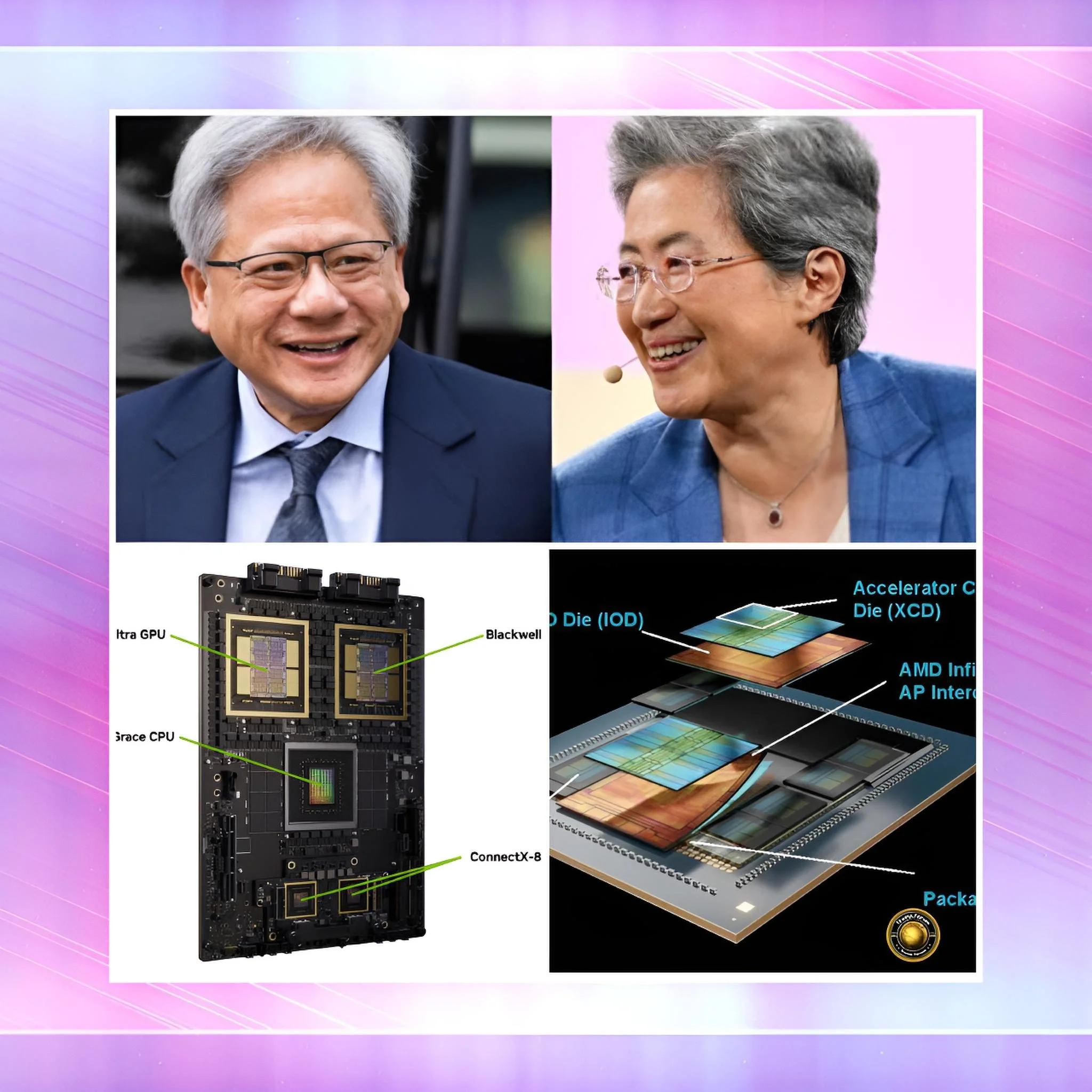

Full-Stack System Integration as Competitive Leverage

NVIDIA's competitive advantage has evolved beyond hardware into integrated system design spanning compute, memory, networking, and software orchestration.

The company no longer sells merely GPUs but relatively complete systems, such as the Blackwell-based NVL72 rack, which contains 72 compute GPUs integrated with advanced interconnects, networking adapters, custom CPUs, and application-specific software libraries. This rack-scale systems approach provides multiple competitive advantages unavailable to component-level competitors.

First, full-stack integration reduces customer complexity. Rather than sourcing GPUs from Nvidia, CPUs from third parties, networking adapters from distinct suppliers, and orchestrating compatibility across heterogeneous components, customers purchase a validated system where Nvidia engineers have optimized interactions across layers.

The customer avoids the engineering burden of component integration and gains implicit assurance that system components have been validated to work cohesively.

Second, integrated systems create higher barriers to competitive displacement. A competitor offering superior GPU performance but lacking equivalent CPUs, networking, memory, and software integration cannot match Nvidia's total solution.

Customers evaluating alternatives must commit not merely to GPUs but to entire alternative ecosystems, incurring system-wide redesign costs far exceeding the costs of single-component switching.

Third, full-stack integration enables Nvidia to maintain a technological advantage in total-cost-of-ownership calculations even when individual components appear less compelling. NVIDIA's internal studies suggest that TCO advantages so substantially favor NVIDIA systems that competitors' products would need to be entirely free to constitute rational purchasing decisions. While such claims have a promotional character, they reflect genuine truths about the advantages of system-level optimization.

The Vera CPU integration arriving in 2026 alongside Rubin architectures exemplifies this strategy. NVIDIA has designed eighty-eight custom ARM cores, branded Vera, to integrate with Rubin GPUs through a 1.8 terabit-per-second NVLink connection. This integration provides 100-fold performance improvements in CPU-GPU workloads while multiplying power consumption by only 3—an efficiency gain that generalist CPUs cannot match.

For inference workloads that include sequential reasoning components unsuited to GPU parallelism, the Vera CPU provides capabilities unavailable through external CPU procurement.

Annual Release Cadence as Strategic Weapon

The most sophisticated element of Nvidia's competitive strategy is the deliberate shift from biennial architectural releases to an annual cadence.

Historically, semiconductor vendors released new architectures approximately every two years, providing competitors with reasonable time windows to develop and deploy competitive alternatives.

Intel's previous competitive strength against AMD in CPU markets rested partly on superior execution of two-year design cycles, which allowed it to accumulate incremental advantages before competitors could respond.

NVIDIA's acceleration to annual architectural release cadence—Blackwell (2024), Blackwell Ultra (2025), Rubin (2026), Rubin Ultra (2027), Feynman (2028)—deliberately prevents competitive catch-up. By the time AMD's competing MI350 reaches meaningful deployment volume in 2026, Nvidia will have already released Rubin.

By the time Intel's Falcon Shores reaches production in 2027, Nvidia's Rubin Ultra and its Feynman plans will already be public.

Competitors operating on traditional two- to three-year design cycles cannot maintain pace with this cadence.

The mechanism is simple: if a competitor takes 2 years to design, validate, and manufacture a new architecture, Nvidia will have released an entire generation by the time the competitor's product ships.

Furthermore, Nvidia's annual releases, each incorporating genuine performance-per-watt improvements, continuously expand the performance gap that competitors must overcome.

A competitor shipping two-year-old technology relative to Nvidia faces not merely Nvidia's current generation but must overcome Nvidia's generational lead, making catch-up mathematically difficult.

Latest Facts and Concerns: Supply Constraints, Pricing Pressures, and Emerging Risks

Supply Constraints, Pricing Pressure, and the Competitive Response to Custom Silicon Economics

Supply Chain Constraints as Competitive Advantage

NVIDIA's supply position paradoxically strengthens its market dominance, even as it creates near-term allocation challenges. TSMC's CoWoS packaging capacity, essential for Blackwell and H200 production, is fully utilized through mid-2026.

HBM supply from Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron remains constrained, with demand exceeding available capacity for the highest-end configurations. Blackwell demand exceeds supply by extraordinary multiples: hyperscalers place orders for systems they will not receive until 2027 or 2028.

Rather than constituting competitive vulnerability, supply constraints reinforce customer lock-in. A hyperscaler unable to obtain Nvidia systems must either accept long delivery delays or commit to alternative suppliers' products.

Yet alternative products from AMD and Intel require re-optimization of the software ecosystem, rendering their advantage moot if deployment delays mean systems arrive when the intended workload has already evolved.

Supply constraints turn Nvidia's limited production into a forcing function, locking customers into the Nvidia ecosystem while they wait. Competitors offering immediately available alternatives cannot overcome the disadvantage of being second-choice vendors for customers who prefer Nvidia but accept alternatives due to delivery delays.

This supply advantage appears likely to persist through 2026. TSMC has committed to expanding capacity to support Nvidia products, but manufacturing capacity expansions take years from conception through production ramp.

Chinese demand for H200 units—estimated at over two million units for 2026, against a current inventory of seven hundred thousand—will consume available supply, preventing any near-term relief. The implication is that Nvidia's supply constraints will likely persist through 2026 and 2027, continuously reinforcing customer lock-in.

Custom ASIC Threat Assessment and Risk Management

The threat posed by hyperscaler custom silicon development warrants serious consideration, yet current evidence suggests a more limited competitive impact than popular industry discussion suggests.

Google's TPU program, while technologically accomplished, remains primarily internal. Meta's interest in TPU purchases validates the feasibility of custom ASICs but does not constitute a broad competitive threat; Meta's specific workloads involve recommendation systems and social media inference patterns unique to its business model.

AWS Trainium's availability beginning in 2026 creates a competitive option for companies choosing Amazon infrastructure, but it benefits from cost advantages specific to Amazon's scale that other organizations cannot replicate.

The critical constraint on custom ASIC economics remains design cycle length and market risk. The twelve to twenty-four month development timescale means that custom ASICs designed to match today's competitive landscape frequently arrive to find the landscape substantially altered.

NVIDIA's annual release cadence exploits this timing asymmetry mercilessly. A hyperscaler launching a custom ASIC program in 2024, hoping to compete with Blackwell, may deploy the chip in 2026 only to discover that Nvidia's Rubin architecture has already emerged and is substantially superior. The custom ASIC, requiring years of follow-on development to match Rubin, becomes obsolete before realizing full value.

This competitive dynamics explains the empirical finding that custom silicon markets remain restricted to mega-hyperscalers. Google, Amazon, and potentially Meta possess sufficient scale and technical sophistication to justify the engineering investment and absorb the obsolescence risk.

Broadcom, functioning as a systems design partner for hyperscaler custom silicon, has positioned itself to capture design services revenue. But the broader market of enterprises, mid-scale cloud providers, and smaller organizations lacks the scale to justify custom development. For these customers, Nvidia's generalist GPUs remain the only economically viable option.

Pricing Pressure and Margin Compression Concerns

The most significant near-term threat to Nvidia's profitability involves potential pricing pressure as competitive alternatives mature. Blackwell GPUs currently command prices of 30,000 to 35,000 dollars per unit, with premium variants exceeding 40,000 dollars.

AMD's MI355X offers comparable performance at potentially lower cost per unit, creating pressure for Nvidia to reduce prices or demonstrate superior value to justify the pricing differential.

The risk is not catastrophic but merits serious attention. NVIDIA's gross margins on data center GPUs currently exceed seventy percent, among the highest in semiconductor history.

Even modest pricing pressure would compress these margins to sixty-five or sixty percent, reducing profitability despite sustained volume growth. If the cost advantages of custom ASICs materialize more decisively than current data suggests, hyperscalers, representing perhaps 30 to 40 percent of Nvidia's business, might diversify their silicon spending, reducing Nvidia's addressable market.

However, this pricing pressure risk remains constrained by the ecosystem advantages previously discussed. Customers unwilling or unable to absorb the software ecosystem switching costs of AMD platforms will accept Nvidia's pricing rather than become pioneers in ROCm adoption.

This heterogeneity enables Nvidia to maintain pricing power despite competitive alternatives. The company's internal economic calculus suggests that superior TCO justifies its current pricing relative to other options, and customers' evaluations of total cost rather than unit price support this positioning.

Cause and Effect Analysis: How Nvidia Maintains Dominance Despite Competitive Intensity

How Ecosystem Lock-in and Innovation Velocity Sustain Dominance Despite Genuine Competition

The competitive dynamics observable in January 2026 reflect a specific causal chain worth analyzing. AMD's technical achievements with MI355X architecture are genuine; the product represents serious engineering excellence and credible performance parity with Blackwell in several dimensions. Yet AMD's market share gains remain marginal despite technical merit. This apparent paradox requires explanation.

The explanation involves the distinction between technological capability and market dominance. Technological capability—the ability to manufacture chips that meet or exceed competitors' specifications—proves necessary but insufficient for market dominance.

Market dominance additionally requires commercial viability, customer lock-in through ecosystem switching costs, supply chain leverage, and sustained innovation velocity. AMD possesses technological capability but lacks the ecosystem, commercial position, and innovation velocity that Nvidia has accumulated over nineteen years.

The causal chain begins with the introduction of CUDA in 2006. The ecosystem development that followed was not foreordained; AMD could have theoretically invested equally in a competitive software ecosystem.

Yet the reality of corporate incentive structures, the difficulty of ecosystem displacement, and Nvidia's relentless focus on ecosystem monetization created an asymmetric development trajectory.

By 2015, when AMD began serious competitive efforts with ROCm, Nvidia's ecosystem advantage had already become substantial. AMD's current investment in ROCm, while serious, comes at a structural disadvantage: AMD must invest more (relative to Nvidia's investment) while accepting lower returns (smaller developer base, fewer validated applications) for years before achieving ecosystem parity.

This ecosystem asymmetry creates lock-in, allowing Nvidia to maintain pricing power and market dominance despite competition. NVIDIA's adopted annual release cadence serves as a force multiplier for this ecosystem advantage.

By maintaining technological superiority and committing to generational improvement through annual releases, Nvidia forces customers to view platform-switching decisions in terms of multi-year ecosystem investment rather than single-product-cycle performance comparisons.

A customer evaluating whether to switch from Nvidia to AMD must commit not merely to Nvidia's current product but to a multi-year platform relationship.

The dynamics of supply chain constraints further reinforce this causal mechanism. NVIDIA's supply dominance forces customers to allocate their budgets to NVIDIA systems while they wait for delivery.

By the time capacity becomes available and custom ASIC alternatives mature, customers have structured their systems architectures around Nvidia infrastructure and would incur significant redesign costs to transition.

Future Steps: Competitive Response Strategies and Market Evolution Through 2030

AMD's Growth Path, Custom Silicon Limits, and Hyperscaler Capital Allocation Through 2030

NVIDIA's Competitive Response Architecture

NVIDIA's management has articulated a coherent strategic response to competitive challenges that extends through 2030 and beyond. Rather than attempting to prevent competition through restrictive business practices or technological secrecy, Nvidia has adopted a strategy of relentless competitive acceleration.

The annual architecture release cadence serves as the primary mechanism: by continuously improving performance and efficiency, Nvidia aims to render competitors' products increasingly obsolete by the time they reach market.

The Rubin architecture, arriving in late 2026 with the integrated Vera CPU, represents the next iteration of this competitive response. Performance improvements of approximately ten times relative to Blackwell in inference workloads would represent a generational leap sufficient to render mid-2024 custom ASIC programs obsolete.

The Rubin Ultra variant, set to appear in 2027, will further accelerate this trajectory. Feynman, arriving in 2028, promises additional architectural innovations that would further extend Nvidia's performance lead.

Alongside these hardware developments, Nvidia has committed to expanding its ecosystem. CUDA-Q integration for quantum computing, Nemotron model development for inference optimization, Omniverse platform for digital twin applications, and Enterprise AI Factory validated design reference all serve to deepen Nvidia's software moat while expanding addressable markets.

The strategy is deliberate: deepen the CUDA ecosystem advantage while continuously expanding applications of Nvidia infrastructure.

AMD's Competitive Trajectory and Market Share Outlook

AMD's path forward involves continued architectural refinement and the maturation of its software ecosystem. The MI400 architecture, anticipated for a 2026-2027 release, promises further memory improvements (potentially up to 432GB+) and efficiency gains.

The Helios AI Rack system, designed to compete directly with Nvidia's NVL72 and future systems, represents AMD's commitment to full-stack integration.

Yet AMD faces structural constraints that likely limit market share growth. Achieving ecosystem parity with CUDA within a five-year timeframe appears mathematically implausible given the investment differential and developer population asymmetries.

AMD's more realistic competitive pathway involves capturing specific market segments where ecosystem matters less—inference-specific applications, organizations with existing AMD relationships, and cost-sensitive deployments where 30% price advantages overcome switching costs.

Analysis suggests AMD could realistically capture twelve to fifteen percent market share by 2030, primarily in inference and cost-sensitive segments.

This represents meaningful competition but falls short of challenging Nvidia's dominance. AMD's success would likely come through price-competitive positioning and market segment focus rather than head-to-head performance competition.

Custom ASIC Market Evolution

The custom ASIC market will likely remain restricted to mega-hyperscalers through 2030 and beyond. Google's TPU and Amazon's Trainium programs will continue refining their respective architectures, extracting measurable efficiency gains for internal operations and cloud customer offerings. Yet the economic barriers to entry remain so substantial that new entrants face prohibitive obstacles.

The critical question involves whether custom ASIC economics will improve sufficiently to justify broad adoption beyond the mega-hyperscaler tier. If Nvidia's annual release cadence falters—if Feynman arrives late or underperforms expectations—custom-ASIC ROI improvements could make custom-silicon investment more defensible for smaller organizations. However, barring Nvidia execution failures, custom silicon remains restricted to specialists.

The implication is a bifurcated competitive market: Nvidia capturing eighty percent plus of the broad market through superior ecosystem, performance, and integration, while custom ASIC providers capture fifteen to twenty percent of the hyperscaler-exclusive segment.

This bifurcation is healthy for industry diversity but does not threaten Nvidia's dominance.

Hyperscaler Capital Allocation and Competitive Implications

Hyperscaler capital allocation decisions will prove critical to competitive evolution. If hyperscalers allocate most of their capex to Nvidia systems (as current data suggests), Nvidia's market position will continue to strengthen. If hyperscalers begin allocating substantial percentages of AI capex to custom silicon, the calculus shifts.

Current evidence suggests the former: estimates indicate that while hyperscaler capex reaches three hundred billion dollars in 2025, Nvidia GPU spending represents seventy to eighty percent of this allocation, with custom silicon representing only fifteen to twenty percent.

However, this ratio could shift if custom ASIC programs become more reliable and Nvidia's premium pricing begins driving customer exploration of alternatives. The critical threshold appears to involve whether custom silicon's cost advantages exceed ecosystem switching costs.

At current calculations, switching costs exceed the savings from custom ASICs for most organizations; if this gap narrows, competitive dynamics could shift.

Conclusion: Dominant Competition and the Durability of Nvidia's Market Position

The artificial intelligence accelerator market in 2026 exhibits characteristics of oligopoly rather than monopoly or perfect competition.

NVIDIA maintains overwhelming dominance, but AMD, custom ASICs, and Intel collectively present meaningful competitive challenges that cannot be dismissed.

The market is transitioning from Nvidia's uncontested reign to a competitive landscape where maintaining leadership requires strategic excellence rather than technological inevitability.

Analysis of competitive dynamics suggests that Nvidia's market position will likely prove durable through 2030 and beyond, but not without severe competitive pressure. The company's ecosystem advantage, integrated full-stack approach, and annual release cadence provide formidable defenses against competitive displacement.

AMD's improvement trajectory suggests capture of perhaps 10 to 15 percent of market share in specific segments, a meaningful development but insufficient to challenge dominance. Custom ASIC development by hyperscalers will accelerate, but structural economics limit this competition to mega-scale operators.

Dominant Competition and the Durability of Nvidia's Market Position Through the Next Decade

The path forward for Nvidia involves sustained innovation velocity, ecosystem deepening, continued integration of full-stack systems, and pricing discipline. Competitors will continue improving, and some market share will inevitably migrate to alternatives.

Yet the combination of ecosystem switching costs, integrated systems advantage, and innovation velocity suggests Nvidia will maintain seventy-five to eighty-five percent market share through 2030. This represents material competitive pressure relative to its current 90% position, but it continues to constitute dominant market leadership.

For investors, customers, and policymakers, the implication is clear: Nvidia's dominance remains material and likely durable, but it assumes continued execution excellence across multiple dimensions.

The company faces no existential competitive threat, but neither can it assume dominance will persist without sustained competitive effort.