Trump’s Tough Second Year: Big Promises, Hard Reality

Summary

Trump’s second year back in the White House is proving harder than he expected. He has more control over his own team than before, but the world and the country are still not doing what he wants. This year feels like a stress test: it will show whether his way of acting—loud, fast, and forceful—can really solve big, long‑running problems.

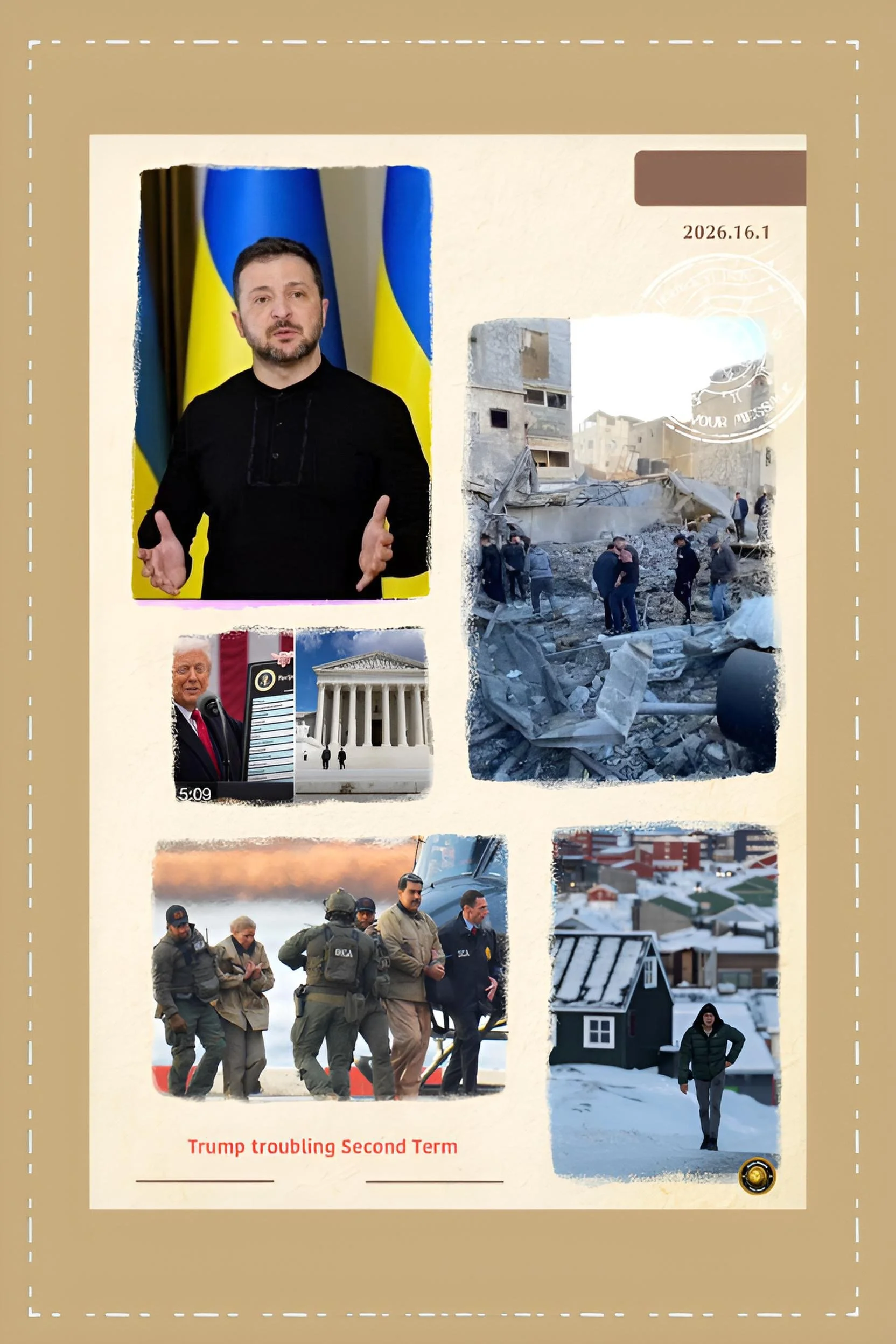

Take the war between Russia and Ukraine. Trump said he could end it in just one day if he became president again. Many voters liked that promise because the war has gone on for years and has hurt energy prices and security in Europe. But after a year in office, the war is still going.

The United States wrote a long plan for peace, but Russia will not accept rules that bring Western soldiers or strong protection for Ukraine, and Ukraine will not agree to give up its land. It is like trying to make two neighbors sign a deal when one wants to keep stealing the other’s yard and the other refuses to move the fence.

In the Middle East, Trump created a 20‑point plan to calm Gaza and show he could bring peace where others failed. In practice, the plan is stuck at an early stage. People in Gaza are still suffering, and trust between leaders is very low. Violence from some Israeli settlers against Palestinians in the West Bank has increased, which makes things even worse. Important countries such as Saudi Arabia are saying: “We will not move closer to Israel unless there is a real path for a Palestinian state.” Imagine trying to build a new house on shaky ground: every time you add a floor, the structure wobbles because the base is not stable.

Iran adds another layer of trouble. Years of sanctions and poor management have badly damaged Iran’s economy. Many Iranians have gone into the streets to protest, and security forces have answered with deadly crackdowns.

The United States has hit Iran and its partners with more pressure, including strikes and tighter restrictions, hoping to force the government to back down on its nuclear and regional plans. So far, Iran has not given up. Instead, it uses armed groups in other countries to send its own message and cause problems for U.S. allies. It is like pushing down on one part of a balloon and watching it bulge somewhere else.

Then there is Venezuela. The Trump administration decided to use strong tools there: a naval blockade, attacks on certain targets, and support for moves that led to the capture of top people around Nicolás Maduro. This shook up politics in Venezuela and also hit Russian oil operations that depended on that country. Some people in the United States see this as proof that Trump is willing to act boldly and punish enemies. But Russia sees it as a real threat to its money and influence, and that can push Moscow to hit back in other ways, such as cyberattacks or helping U.S. rivals in other regions.

The Greenland issue shows a different problem: it has angered allies instead of enemies. Trump wants more control or special rights over Greenland because it has important minerals and sits in a strategic Arctic location. Many leaders in Europe are furious.

They feel the United States is treating Greenland like something to be grabbed, not a place with its own people and ties. This is happening at the same time that NATO is trying to stay united against Russia and deal with new dangers in the Arctic. It is as if a captain, in the middle of a storm, suddenly starts a fight with his own crew over who owns part of the ship.

All these fights abroad link back to politics at home. New polls show that many Americans think Trump’s policies have made the economy worse in his second term.

In his first presidency, he often had stronger ratings on the economy than on other issues, but now that advantage is fading. Everyday examples matter: people see higher bills, worry about jobs and prices, and feel worn out by constant drama. For them, talks about big foreign “wins” mean less if their own lives do not improve.

The coming 2026 midterm elections will be a big check on Trump’s power. History suggests that the president’s party usually loses seats in Congress during midterms, and this time there are many tight House races where a small shift could flip control.

Democrats are trying to use public frustration over the economy and foreign policy to win these districts. At the same time, Trump’s strong backers are fired up by his tough line on immigration and his claims that he alone can protect the country. The result could be a very close and bitter fight, with control of Congress coming down to a small number of seats.

The deeper question is whether Trump can change course when his usual methods stop working. His style is to push hard, move fast, and promise big results. That can create a sense of action and energy. But over time, other leaders in the world learn how to resist or wait him out, and many Americans grow tired of one crisis after another.

Trump has two basic choices in this second year. He can double down: more pressure, more threats, more talk of “historic” deals just around the corner. That might excite his base but raise the risk of mistakes and new conflicts. Or he can slow down: work more with allies, accept smaller but real steps forward, and focus on fixing daily problems at home. That path is less dramatic but more likely to build stable results.

For now, the evidence points to a mix of both approaches, which may not be enough. If he cannot show progress in Ukraine, Gaza, Iran, and the economy before the midterms, Trump could enter the second half of his term weaker, facing a Congress that is less willing to follow his lead. In that case, this “tough second year” would not only be about foreign policy; it would mark the moment when the limits of his whole way of governing become impossible to ignore.