When the Bird Fell in Love with Moon: A Historical Timeline of Cross-Cultural Mythology

Executive Summary

This work delves deeply into the intricate tapestry of myths surrounding the enchanting connection between birds and the moon, drawing from various cultures throughout history.

The narrative unfolds a timeline highlighting significant stories, beliefs, and symbols that illustrate how different societies have perceived this celestial body and its relationships with avian creatures.

From ancient civilizations that viewed the moon as a deity, revered in their rituals, to tribes that crafted tales of birds guiding souls to the afterlife, this exploration captures the essence of human imagination and reverence for nature.

Each chapter immerses readers in the rich lore, showcasing how the moon has been personified in mythologies as a lover, a guide, or a guardian, while birds are often depicted as messengers or harbingers of change.

Many cultures believed that the moon and birds shared a profound bond—birds were seen as vehicles for communication between the earthly realm and the divine.

The publication work intricately weaves together symbolism, art, and folklore, bridging geography and time, as it highlights how diverse cultures have celebrated this celestial romance through poetic verses, vibrant artwork, and oral traditions passed down through generations.

Introduction

The question “When did the bird fall in love with moon?” reveals a fascinating journey through human civilization, spanning over three millennia of cultural development.

Rather than a single moment in time, this poetic concept represents multiple independent emergences across diverse cultures, each reflecting humanity’s eternal fascination with celestial beauty and impossible love.

The timeline of these mythological traditions reveals how universal themes transcended geographical and temporal boundaries, creating remarkably similar stories of avian devotion to lunar majesty.

The earliest documented instances of this celestial romance appear in ancient Indian texts, while parallel traditions developed independently in China and later spread throughout East Asia.

Contemporary interpretations continue this tradition into the digital age, demonstrating the enduring power of this metaphor for human longing and connection across impossible distances.

The Vedic Origins: 1500-1200 BCE

The oldest traceable origins of bird-moon symbolism emerge from the Rigveda, composed between 1500-1200 BCE during the early Vedic period.

While specific references to the Chakora bird’s love for the moon may not appear explicitly in these earliest texts, the Rigveda establishes the foundational framework for celestial-terrestrial relationships that would later flourish in Hindu mythology.

The Rigveda’s significance lies in its establishment of complex relationships between earthbound creatures and celestial bodies, creating the mythological groundwork upon which later traditions would build their specific narratives of avian lunar devotion.

These texts, preserved through extraordinary oral traditions spanning millennia, represent humanity’s earliest recorded attempts to understand the connection between terrestrial longing and celestial beauty.

The Brahmanic Codification: 6th Century BCE

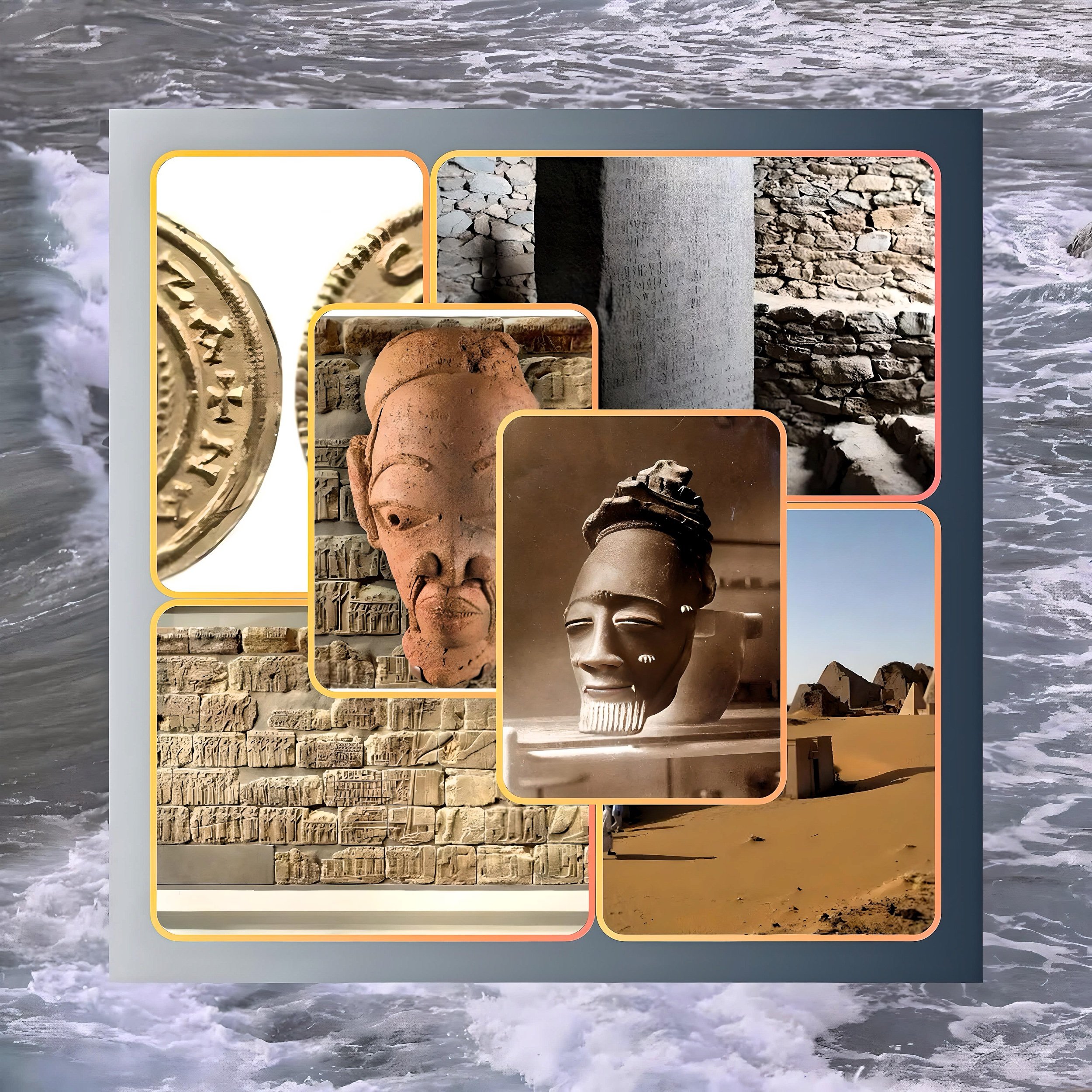

The first explicit mention of a hare dwelling on the moon appears in the Jaiminiya Brahmana, composed around the 6th century BCE, predating the establishment of Buddhism.

This text states clearly: “He is a hare (sasa-) who is dwelling in the Moon,” establishing what may be the world’s first documented instance of a specific animal’s celestial residence.

The Shatapatha Brahmana, another 6th-century BCE text, reinforces this tradition, providing multiple independent sources for the moon-dwelling hare mythology.

These Brahmanic texts explain the connection through linguistic wordplay, noting the similarity between “control” (sasti) and “hare” (sasa), suggesting the moon’s dominion over earthly affairs through its rabbit resident.

Archaeological evidence supports these textual traditions: ancient Indian coins from approximately 180 BCE depict clear images of hares on the moon, demonstrating that this mythology had become sufficiently established to warrant inclusion in official iconography.

The moon’s association with cycles of death and rebirth, combined with the hare’s reputation for fertility, created powerful symbolic connections that resonated across ancient Indian culture.

The Buddhist Transformation: 3rd Century BCE

The Sasa-Jataka, a Buddhist tale whose prototypes are believed to have been established around the 3rd century BCE, transforms the simple presence of a hare on the moon into a narrative of ultimate sacrifice and divine recognition.

In this story, the god Indra, disguised as a hungry Brahmin, tests various animals by requesting food.

When a hare offers to sacrifice itself in fire to provide sustenance, Indra draws the hare’s figure on the moon’s surface as eternal recognition of this selfless act.

This Buddhist interpretation establishes themes that would echo across cultures: the idea of sacrifice leading to celestial immortality, divine recognition of noble hearts, and the moon as a canvas for eternal remembrance.

The story’s integration into Chinese records by the 7th-century monk Xuanzang demonstrates early cross-cultural transmission of these themes.

Chinese Parallel Development: 4th-3rd Centuries BCE

Remarkably, Chinese culture developed its own moon-dwelling creature tradition independently during approximately the same period as the Buddhist Jataka tales.

The Chu Ci anthology, written by Qu Yuan in the 4th-3rd centuries BCE, contains the earliest Chinese reference to a creature dwelling on the moon, though scholars debate whether the original term referred to a rabbit or toad.

Definitive visual evidence appears in the silk paintings from the Mawangdui Han tombs (2nd century BCE), where both a toad and rabbit appear alongside a crescent moon.

These archaeological artifacts, from the tomb of Changsha Kingdom prime minister Li Cang and his wife Xin Zhui, provide concrete proof that moon rabbit mythology was well-established in Chinese culture by the Western Han period.

The Chinese tradition emphasizes the rabbit’s role in creating the elixir of immortality, with Tang Dynasty poet Li Bai (701-762 CE) writing: “The rabbit in the moon pounds the medicine in vain”.

This pharmaceutical focus distinguishes Chinese moon rabbit folklore from its Indian sacrificial counterpart, though both emphasize themes of immortality and celestial service.

The Hindu Classical Synthesis: 3rd-5th Centuries CE

The Chakora bird’s specific association with moon-love reaches full literary expression in classical Sanskrit drama, particularly in the Mricchakatika (The Little Clay Cart), attributed to King Shudraka and dated to the 3rd century CE.

This play explicitly describes the Chakora as feeding on moonbeams, establishing the bird’s exclusive dietary devotion to lunar light.

The Markandeya Purana (c. 250-500 CE) further codifies Chakora mythology, placing it within established Hindu cosmological frameworks.

The text describes the bird’s extraordinary behaviors: drinking water only during the moon’s transit through Swati Nakshatra, maintaining continuous nightlong vigils gazing at the moon, and surviving solely on moonbeam nourishment.

These classical sources transform earlier astronomical observations into sophisticated metaphors for spiritual devotion, particularly in Vaishnavism where the Chakora represents the devotee’s relationship with divine love.

The bird’s patient, unrewarded love becomes a model for pure devotion that expects nothing in return yet remains eternally constant.

East Asian Cultural Transmission: 10th-11th Centuries CE

Japanese adaptation of moon rabbit folklore appears in the Konjaku Monogatarishū, a collection of over 1,000 stories compiled during the late Heian period (10th-11th centuries CE).

This represents the culmination of several centuries of cultural transmission from China through Korea to Japan, with each culture adding distinctive elements to the core narrative.

Japanese versions emphasize mochi-pounding rather than elixir-making, reflecting local cultural practices and seasonal celebrations like Tsukimi (moon-viewing festivals).

Korean tradition develops the Daltokki story, focusing on rice cake preparation under a gyesu tree, emphasizing family unity and selflessness.

The remarkable consistency across these East Asian variations suggests both active cultural transmission and independent parallel development responding to universal human psychological needs for meaning in celestial observation.

Contemporary Digital Revival: 21st Century CE

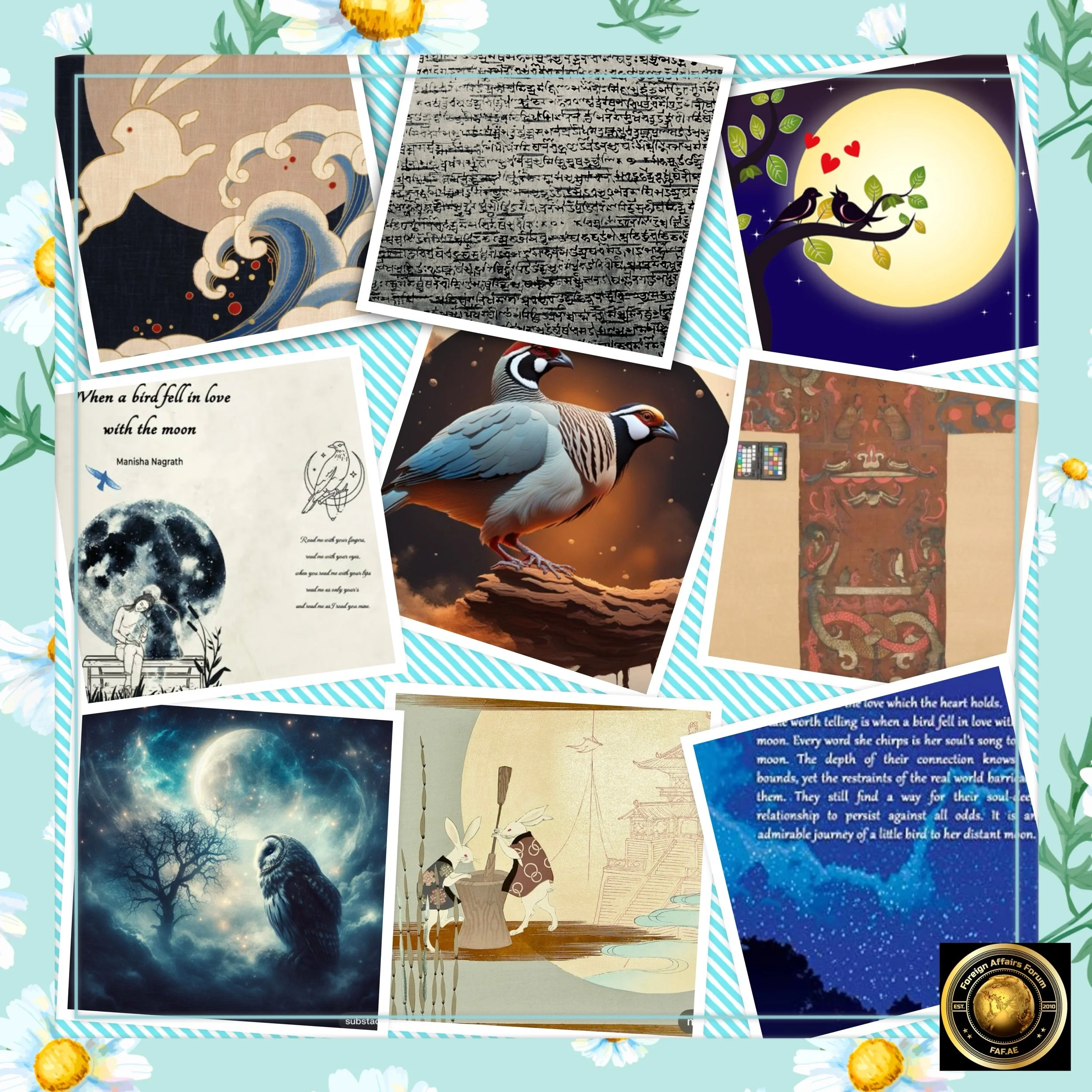

The most recent iteration of this ancient theme appears in Manisha Nagrath’s 2021 poetry collection “When a Bird fell in love with the Moon,” published by Blue Rose Publishers.

This contemporary work transforms classical metaphors into explorations of digital-age romance, virtual connections, and long-distance relationships enabled by modern technology.

Nagrath’s interpretation demonstrates the enduring relevance of ancient symbols for modern emotional experiences.

The bird represents earthbound lovers constrained by physical limitations, while the moon symbolizes beloved partners who remain emotionally present yet physically distant.

This 21st-century adaptation shows how 3,500-year-old metaphors continue to provide language for humanity’s newest forms of connection and separation.

When a Bird Fell in Love with the Moon” by Manisha Nagrath

The phrase "When the bird fell in with the moon" evokes a poignant narrative that captures the essence of the book in question.

The author weaves a rich tapestry, presenting an emotional saga about a bird that finds itself deeply enamored with the moon.

This tale brilliantly encapsulates themes of yearning and unrequited love, allowing readers to immerse themselves in the interplay of joy and heartache.

At its core, the story delves into the bird’s profound feelings of affection, despite its acute awareness of the moon’s distant and unattainable nature.

Through lyrical and evocative storytelling, the narrative explores the exquisite beauty and bittersweet pain associated with long-distance love, illustrating the struggles of desiring what is forever out of reach.

This collection distinguishes itself in the realm of contemporary poetry, not only for its narrative unity but also for its capacity to engage readers through a cohesive love story rather than a series of fragmented verses.

The author skillfully guides the audience through a single, heartfelt journey that resonates deeply.

The work is a powerful testament to the idea that love can transcend physical distances, navigate political boundaries, and bridge cultural divides.

It artfully presents the timeless human experience of longing and connection through the metaphor of grounded creatures yearning for celestial wonders, inviting readers to reflect on their own experiences of love and distance.

Conclusion

The Eternal Moment of Falling in Love

The bird’s love for the moon represents not a single historical moment but a recurring human realization that spans millennia.

From the Rigveda’s 1500 BCE establishment of celestial-terrestrial relationships to contemporary digital-age poetry, each culture has independently discovered this metaphor’s power to express humanity’s deepest longings.

The timeline reveals fascinating patterns: the 6th century BCE emergence of explicit moon-dwelling creature stories in both Indian and Chinese cultures, the 3rd-century CE classical synthesis in Sanskrit literature, and the medieval East Asian cultural transmission creating regional variations on universal themes.

Perhaps most remarkably, the question “When did the bird fall in love with moon?” cannot be answered with a specific date because this love story repeats endlessly across cultures and centuries.

Each time human beings look up at the moon and feel the pull of impossible beauty, each time earthbound hearts reach toward unreachable light, the bird falls in love with the moon again.

The mythology’s persistence across 3,500 years suggests that this moment of celestial romance represents something fundamental about human nature—our capacity to find meaning and beauty in longing itself, transforming the pain of unreachable desire into sources of hope, poetry, and spiritual transcendence.