The Trillion-Dollar Mirage: Why Protectionism is Choking India’s 2026 Export Dream - Part II

Executive Summary

The aspirational milestone of $1 trillion in total exports for India in 2026 appears increasingly out of reach, with credible economic analyses projecting a shortfall of approximately $150 billion.

While the services sector continues to demonstrate remarkable buoyancy, potentially breaching the $400 billion mark, the merchandise trade sector faces a formidable ceiling imposed by geopolitical friction and protectionist headwinds.

The convergence of a severe 50% tariff regime from the United States and sluggish global demand has effectively neutralized the growth velocity required to hit the trillion-dollar target within the current fiscal timeframe.

Consequently, 2026 will likely be characterized not by the celebration of a numerical milestone but by a strategic retrenchment and a frantic search for alternative markets to offset the deceleration in traditional Western trade corridors.

Introduction

India’s roadmap to becoming a developed economy by 2047 has long been anchored by intermediate milestones, the most prominent being the target of $2 trillion in exports by 2030. Within this trajectory, 2026 was envisioned as a pivotal year where total exports—comprising both goods and services—would arguably cross the psychological threshold of $1 trillion.

This optimism was predicated on the twin engines of high-value manufacturing and digital services. However, the economic reality of late 2025 has sharply diverged from these projections.

The global trading architecture has shifted from an era of open integration to one of fragmented, security-driven blocs. For an emerging power like India, which relies on open markets to fuel its industrial rise, this new environment poses an existential check on its export-led ambitions.

The question is no longer about the inevitability of India’s rise, but whether its structural agility can outpace the external barriers erected against it.

Key Developments Needed

Achieving the $1 trillion figure in 2026 would have required perfect alignment between domestic capacity and external demand, a scenario that has not materialized.

Specifically, the merchandise sector needed to grow at a compound annual rate exceeding 15% to complement the steady rise in services. Instead, goods exports have plateaued, mainly, hovering near $437 billion.

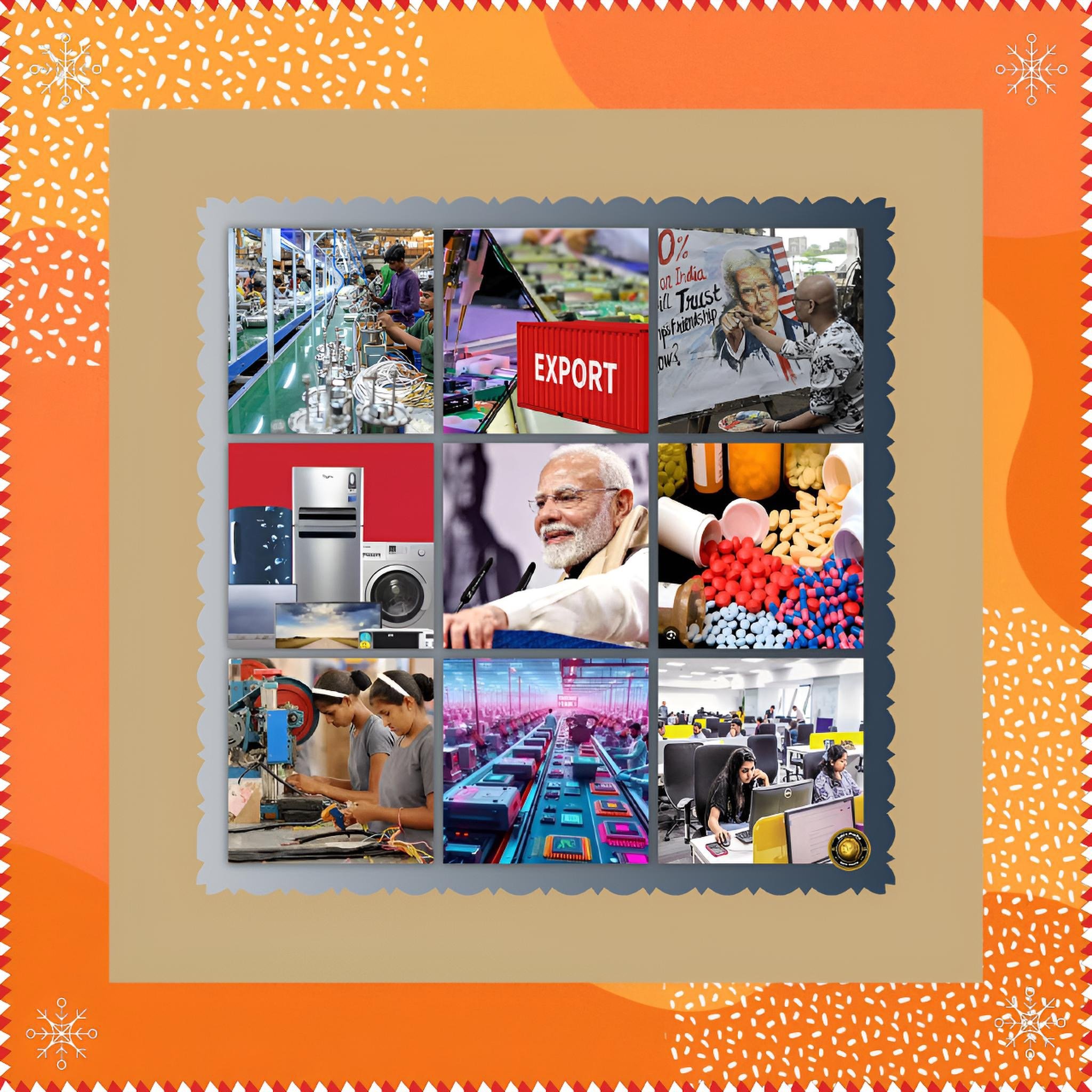

To meet the target, a sudden and unlikely reversal of US trade policy would be necessary, alongside immediate ratification of the India-EU Free Trade Agreement. Furthermore, the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes, while successful in electronics, would have needed to deliver instantaneous, large-scale export surpluses across textiles, automobiles, and specialty chemicals—sectors that are currently contracting under the weight of tariffs.

Without a diplomatic breakthrough that dismantles the current 50% tariff wall on Indian goods in the United States, the mathematical pathway to $1 trillion remains obstructed.

Facts and Concerns

The data emerging from the fiscal year ending 2025 paints a sobering picture of “growth without acceleration.” Total exports for FY25 stood at approximately $825 billion, a figure respectable in isolation but insufficient for the exponential leap required.

Forecasts for FY26 suggest a marginal increase to roughly $850 billion, leaving a gaping deficit of $150 billion against the target.

The primary concern lies in the uneven nature of this performance. While the services sector is projected to grow by nearly 14%, effectively shielding the overall trade balance from collapse, the merchandise sector is expected to contract in volume terms.

The United States, traditionally the largest consumer of Indian goods, has seen its imports from India decline by over 28% in just five months due to punitive duties. This creates a dangerous over-reliance on the services sector to mask the risks of deindustrialization emerging in labor-intensive export hubs like Tirupur and Surat.

Cause-and-Effect Analysis

The causality behind this missed target is rooted in the collision between India’s strategic autonomy and American geo-economic leverage. The imposition of escalating tariffs—culminating in the 50% rate in August 2025—served as the primary decelerator.

This policy shock rendered Indian textiles, gems, and leather goods uncompetitive with rivals such as Vietnam and Bangladesh, which do not face similar barriers. The effect was an immediate cancellation of orders and a diversion of supply chains.

Simultaneously, the “China Plus One” strategy, which India hoped to capitalize on, has proven stickier than anticipated; global firms are hesitant to relocate to a jurisdiction currently in the crosshairs of US trade policy. This external pressure forced Indian exporters to absorb costs to maintain market share, eroding profitability and stifling the capital expenditure needed for capacity expansion. The net result is a merchandise export sector that is fighting for survival rather than fueling growth.

Future Steps

To navigate this impasse, India is expected to accelerate a “Look East and South” policy, decoupling its export engine from the transatlantic alliance.

The immediate priority will likely be the operationalization of new trade pacts with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the swift conclusion of the expanded trade deal with the United Kingdom, provided it remains insulated from US pressure.

Domestically, policymakers will almost certainly introduce a “PLI 2.0” focused on export-oriented MSMEs to subsidize the tariff burden and prevent mass unemployment. There will also be a concerted push to expand the services export basket beyond IT and business processes into high-value domains like telemedicine, ed-tech, and engineering R&D, which are less susceptible to physical tariff barriers.

The strategy for 2026 will thus shift from aggressive expansion to defensive diversification, preserving the gains made in services while restructuring the manufacturing base for non-Western markets.

Conclusion

While the $1 trillion export milestone will almost certainly remain elusive in 2026, the shortfall should be interpreted as a reflection of a hostile global environment rather than a failure of domestic capability.

The resilience of India’s services sector proves that the economy retains strong fundamental momentum. However, the stagnation in merchandise exports serves as a critical warning: the era of relying on the Western consumer for industrial growth is drawing to a close.

The year 2026 will be a period of recalibration, where India acknowledges the limits of its old export model and aggressively pivots toward a multipolar trade strategy. The target remains valid, but the timeline must now account for a world where trade is no longer free but weaponized.